by Ben Schrader*

There is an instinctive relationship between heritage and history. If heritage professionals see heritage as a process of presenting the past in tangible (buildings, museums) and intangible ways (dance, festivals), then historians offer understandings of that past and how history has been interpreted.[1] While definitions of heritage are diverse and continue to expand, a common concern is the construction of social identities. The British historian Jessica Moody describes heritage as a ‘present-day process which is used in the creation of identity in a variety of ways. In this sense, heritage is not a physical thing left over from the past, but an actively constructed understanding, a discourse about the past which is ever in fluctuation.’[2]

Because history too is actively constructed and mutable, historians are well equipped to contribute to this process, often working with heritage professionals to produce “heritage”. Such collaboration can be simultaneously productive and controversial. Debates often arise over how the past is represented. The ultimate question for the historian, however, is whose history is heritage representing? This is where historians become essential players.

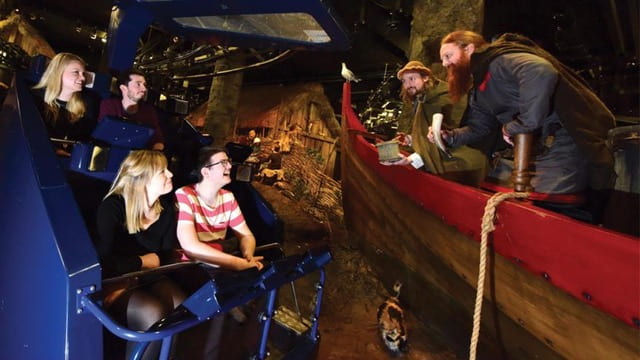

During the 1980s British academic historians attacked places like the Jorvik Viking Centre in York (shown here) for commodifying history and turning it into kitsch tourist spectacles. ‘Heritage is not history’, they proclaimed. (Source: BBC)

“Disneyfying” history

Bonds between history and heritage might seem natural, but they have sometimes been placed in opposite camps. During the 1980s academic historians like David Lowenthal, Robert Hewison and Patrick Wright condemned Britain’s increasing number of open air museums and live interpretations of the past for commodifying history and turning it into kitsch tourist spectacle. What people saw was a sentimentalised and reactionary version of the past in place of the real thing: ‘heritage is not history’, Hewison proclaimed. He and others argued the rise of Britain’s “heritage industry” had been encouraged by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in response to deindustrialisation and social malaise. In promoting a nostalgic and heroic past, heritage diverted people from current problems.[3]

The public historian Samuel Raphael took exception to the characterisation of heritage as a “Disneyfied” version of history. He thought historians’ hostility towards heritage reflected a snobbish ‘belief that the only true knowledge is that which is to be found in books.’[4] Because heritage relies on surface appearance historians viewed it as hopelessly shallow. This position was a result of their training in historical method, where the written word has a ‘privileged place’ and the visual and verbal is held in ‘low esteem.’ The ‘natural habitat’ of the historian was therefore a library rather than a museum.[5] Samuel saw the history discipline as essentially detached from material culture and also thought it resented heritage as an unwanted competitor for the public’s attention.[6]

The point was highlighted in an important 1998 study by the American public historians Ray Rosenzweig and David Thelen. In 1994, they surveyed 1,500 people about how Americans were engaging with their pasts. They found that almost all respondents had engaged in a history-related activity. Respondents valued the past first in terms of their personal and family histories, followed by areas that spoke to their individual and collective identities, and then by particular historical moments or movements. Most were less interested in national history narratives and academic history than in “experiencing” the past in museums and at heritage sites. The study also exposed national counter-narratives from minority groups, who also felt alienated from academic history writing.[7] That relatively few Americans engaged with academic history was a sobering finding, but it was one the discipline was unwilling to confront, instead criticising the study for perceived methodological deficiencies.[8]

Dissonance between academic and popular understandings of the past during the 1990s unleashed the “history wars”. In Australia, research showing the detrimental impact of colonisation on Indigenous peoples led to popular claims that this interpretation maligned white people like James Cook. (Sources: The Conversation)

History Wars

Disagreement between academic and popular understandings of the past came to the fore in mid-1990s and early 2000s in what is sometimes referred to as the “history wars”. The first of these was the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C. to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1945 Hiroshima atomic bomb. The main exhibit was the plane that dropped it (Enola Gay) and the accompanying exhibition was to provide a multi-narrative account of how the event impacted different communities. This approach clashed with a public expectation for a commemorative presentation that supported the national story that the bomb ended the war. It sparked widespread debate as to whether an exhibition should be a depiction of academic scholarship or an expression of public memory and national identity narratives. Pressure from veteran’s groups and conservative pundits meant analysis lost out to the other imperatives and the proposed exhibition was cancelled.[9] Similar conflict occurred in Australia during the 1990s and early 2000s regarding the magnitude of colonial massacres of Aboriginal people and the misrepresentation of their history. Historians’ focus on these issues led Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, (and others) to criticise them for presenting a negative or ‘black armband’ view of the nation’s past and underplaying positive national identity stories.[10] A divergence of views also occurred in Britain during the bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807). African descendant groups criticised the commemorative emphasis on white heroes like William Wilberforce rather than the stories of the enslaved. Historians of the trans-Atlantic slave trade tried to incorporate these ‘unheard voices’ in public exhibitions, but these failed to shift the national identity narrative that abolition was an overwhelmingly positive historical moment.[11]

Jessica Moody states such case studies illustrate how difficult histories generate discord. This dissonance arises from the process of heritage itself, where heritage professionals (including historians) debate cultural meaning. Such negotiation necessitates conflict and acts to support the sense of identity and place of some people at the expense of others by backing particular versions of history. The case studies underscore the importance of incorporating different voices and ideas about the past. She acknowledges this will always be a contested process, but argues historians are well placed to work alongside heritage practitioners and local communities to further democratise history.

Closer bonds in Aotearoa

In Aotearoa, the distance between historians and heritage professionals has been closer than that seemingly experienced overseas. This may be due to the small size of its historical community, so encouraging social and intellectual networking between professionals researching the past. (It is perhaps no coincidence that the academic historian, J. C Beaglehole, was instrumental in creating the New Zealand Historic Places Trust in 1955.) It is true that some academic historians have criticised the growth of Aotearoa’s own heritage industry – the opening of Te Papa Tongarewa/Museum of New Zealand in 1997 led to a flurry of criticism that it presented a Disneyfied version of the past – but more of them have been supportive of the industry and even contributed their expertise to it. And while most still privilege print culture over all others in their research, few would claim that material culture is a hopelessly shallow source.[12] I’m not aware of a similar local study to Rosenzwig and Thelan’s American one concerning how New Zealanders engage with the past. A surrogate might be a 2008 survey by the Te Manatū Taonga which identified that 82 percent of New Zealanders strongly agreed that historic buildings and places contributed to national identity and should be protected.[13] This suggests most New Zealanders have a relatively strong engagement with their past.

As elsewhere, Aotearoa has experienced dissonance between scholarly and popular understandings of its past. Much of this relates to the nation’s colonial history and the absence and misrepresentation of Māori history. For Pākehā who grew up with the understanding that their country had the best race relations in the world, new historical research exposing this falsehood has been both surprising and confronting. While some have accepted these findings and acknowledged colonisation’s detrimental impact on Māori communities, others have sought refuge in the anachronistic “one people” national identity narrative that negates Māori experience.[14] Aotearoa’s own history war is arguably between those who continue to deny the validity of Māori history and those who promote its mainstream acceptance.

In 2017 activist Shane Te Pou drew attention to the contentious history represented by the Nixon Memorial at Ōtāhuhu. Public debate about its meanings led to an agreement to tell the stories of those the heritage place had excluded. (Source: RNZ)

Contesting heritage and history in Tāmaki Makaurau

Tension in representing the colonial past was highlighted in 2017, when the activist Shane Te Pou called for the removal of the Nixon Memorial at Ōtāhuhu. The 13 metre obelisk memorialised New Zealand Wars imperial commander, Colonel Marmaduke Nixon, who in February 1864 led 1,500 troops in an attack on the Māori village of Rangiaōwhia. During the assault Nixon was shot and wounded. His troops responded by killing 12 men and women trying to flee the melee. Nixon died from his injuries three months later and the memorial was erected in his honour in 1868.[15] Te Pou had looked into the monument after his children had asked him about it. He concluded Nixon was a thug who had killed innocent people. ‘It was not right for such a figure to be memorialised’, he told media.

His stance followed in the wake of contentious efforts in the United States to remove monuments to Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee who had defended slavery. Te Pou suggested the Nixon monument should go to a museum where its meanings could be debated. But other Māori leaders disagreed. Ngāti Āpakura and Ngāti Hinetū kaumatua Tom Roa – a descendant of the survivors – didn’t support its removal ‘because a conversation needed to be had to improve New Zealanders understanding of our past. I think it’s essential that these hidden parts of our history are brought to light’.[16] Similarly, Professor of History at AUT, Paul Moon, stated: ‘I don’t think it should be removed at all, if you remove it, it’s like burying our heads in the sand. You might not see it anymore but the history is still there.’[17] A subsequent meeting with Te Pou and Auckland Mayor Phil Goff reached an agreement that the Nixon Memorial would stay but the Māori side of the battle would also be told at the Ōtāhuhu site. This meant that Rangiaōwhia could tell their story – and so affirm their social identity – in a way they were happy with. Options included a plaque or memorial. It was ‘a reasonable and just outcome’, Te Pou thought.[18]

The result supports Moody’s definition of heritage as being less a tangible thing from the past than an actively constructed and fluctuating understanding of it. This makes it a contested process that supports particular versions of the past at the expense of others, hence the importance of incorporating unheard voices about the past at heritage sites to further democratise history. As stated at beginning of this piece, historians are essential players in this process, helping to ensure heritage engages accurately and rigorously with history. As the American historian Daniel Bluestone reminds us, this includes making sure people clearly understand what they are seeing at a historic place. ‘Part of critical seeing, in this context, includes understanding which historic layers and narratives are missing, and which layers have survived through self-conscious constructions of history.’[19]

There are many other heritage or historic places across Tāmaki Makaurau where historic layers and narratives are missing. It would be my hope that the Auckland History Initiative uncovers some of these layers and gives voice to many of the region’s unheard stories. I also hope that historians in the Auckland History Initiative form strong bonds with local heritage professionals. History and heritage might reside in separate lodgings, but they live in the same rather opposite camps, with much shared ground in-between. The history of Tāmaki Makaurau or Auckland is written across its landscape and heritage professionals – archaeologists, geographers, museum curators, kaumātua, architects – can offer insights into this landscape that historians are not trained to see. Such co-operation and dialogue would provide a fuller, more nuanced understanding of the city’s past than historians can possibly generate alone.

*Ben Schrader is an independent historian specialising in urban history. His most recent book is The Big Smoke: New Zealand Cities 1840-1920 (Bridget Williams Books, 2016). He is currently writing a book on the history of built heritage in Aotearoa. He lives in Wellington but also loves Auckland.

[1] Jessica Moody, ‘Heritage and history, in Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, eds, The Palgrave handbook of contemporary heritage research, Palgrave McMillan, Houndmills, 2015, p. 113.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Raphael Samuel, Theatres of memory: past and present in contemporary culture, Verso, London, 1994 (2012 edition), p. 259 and 262.; Rodney Harrison, Heritage: criticalaApproaches, Routledge. London, pp. 98-99; Moody, ‘Heritage and history’, p. 118.

[4] Samuel, Theatres of Memory, pp. 262.

[5] Ibid, pp. 267-8.

[6] Ibid, p. 270.

[7] Harrison, Heritage: Critical Approaches, p. 102, Moody, ‘Heritage and History’, p. 117.

[8] Moody, ‘Heritage and History’, p. 117.

[9] Moody, ‘Heritage and History’, p. 120.

[10] Mark McKenna, ‘Different Perspective on Black Armband History’, Research Paper 5 1997-98, Parliament of Australia, URL: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/RP9798/98RP05 (accessed 2 Jul 2019).

[11] Moody, ‘Heritage and History’, p. 120.

[12] The academic historian Peter Munz was among those who was critical of Te Papa’s historical exhibitions. Peter Munz, ‘Te Papa and the problem of historical truth’, History Now, 6, 1 (2000), pp. 13-16.

[13] Te Manatū Taonga/Ministry for Culture and Heritage, How important is culture? New Zealanders views in 2008 – an overview, Wellington, 2009, p. 13.

[14] This is exemplifed by the Hobson’s Pledge lobby group.

[15] Steve Watters. ‘New Zealand Wars: Will removing New Zealand Wars memorials achieve anything?’ URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/classroom/conversations/new-zealand-wars/new-wars-memorials (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 24 Oct-2017.

[16] ‘Call for Ōtāhuhu colonial leader memorial to go’, Radio New Zelaand, 6 Sept 2017, URL: https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/call-for-otahuhu-colonial-leader-memorial-to-go (accessed 3 July 2019)

[17] ‘Removing monument to colonial commander who led attacks in NZ Wars like burying our deads in the sand, professor says’, Stuff, 6 Sep 2017, URL”

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/96543803/monument-to-colonial-commandeer-who-led-attacks-in-nz-wars-should-be-removed-auckland-man-says (accessed 3 July 2019)

[18] Maori side of the story to be told at controversial Otahuhu monument’, New Zealand Herald, 12 Sept 2017. URL: https://www.nzherald.co.nz.nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11921391 (accessed 3 July 2019)

[19] Daniel Bluestone, Buildings, Landscapes, and Memory: Case Studies in Historic Preservation, W. W. Norton + Co, New York, 2011, p. 210.