Part One

Auckland’s Māori Community Centre: 1947-1970

Part Two

Māori Bards in the Community Centre

Part Three

Resilience

by Nicolas Jones*

For more than 50 years, the Māori Community Centre has stood as an iconic feature of Auckland’s urban landscape and an integral pan-tribal space for city-dwellers. While eventually demolished in 2002, for those that attended and benefitted from its many programmes and facilities, the Centre’s legacy is an important narrative in the history of Tāmaki Makaurau.[1]

The Centre was founded in 1947, built on the corner of Fanshawe and Halsey Street and opposite Victoria Park in the heart of Auckland city.[2] Before its role as a community centre, the building was used as a bulk cargo store for the United States forces during the Second World War and was often used as a recreation centre by American troops, who were encamped on the existing Victoria Park site.[3] After the war, Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser made the building available on a nominal lease in order to establish the first Auckland Maori Community Centre.[4]

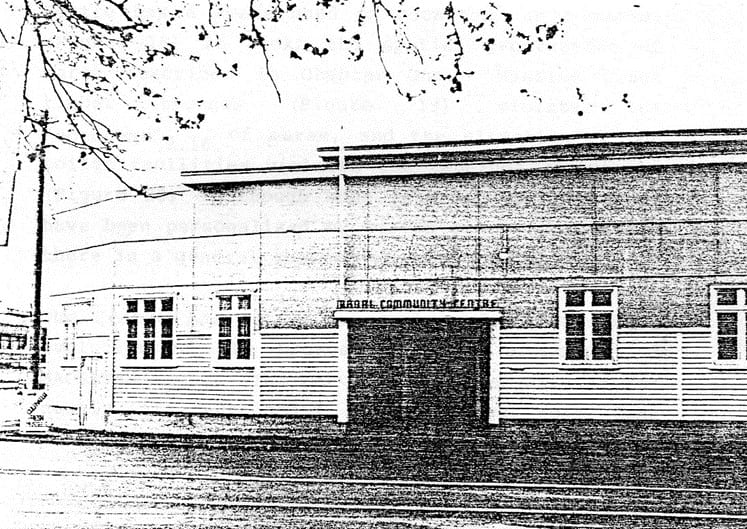

Auckland Maori Community Centre Exterior. Permission from C.M. Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” (Unpublished Thesis, University of Auckland, 1983), 53.

The Maori Trustee and the Maori Lands Board utilised a Government subsidy as well as a generous donation by Auckland Rotary Clubs – who raised 2000 pounds via public appeal –to convert the cargo store into what became the Community Centre.[5] Administered by a Trust Board of fifteen members comprised of the Maori Women’s Welfare League, Rotary, the Returned Servicemen’s Association, and the Waitemata Tribal Executive, this newly founded space was the only Māori community centre within the entire Auckland district. [6] In the same period, over 120 private community halls and approximately seven community halls existed in the inner city area.[7] During the 1960s, the Maori Community Centre lease came under the custodianship of the Ōrākei Marae.[8] For the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, the Maori Community Centre provided a valuable cultural hub, becoming “a temporary Marae for Auckland Maori needs until Orakei Marae was built.”[9]

Aerial Photography 1959 showing location of Maori Community Centre. “Auckland Council GEOMAPS”, Accessed January 21st, 2019. https://geomapspublic.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/viewer/index.html

The period after 1945 witnessed an intensification of rural to urban Māori migration. The allure of the city, particularly that of increasing work opportunities at factories, and the social appeal of city life drew many to Auckland. In 1953, the majority of Māori within Auckland City were not tāngata whenua, nor born from rural immigrants. Rather, most of the Māori population in Auckland at this time were themselves immigrants. The growth of Auckland’s urban Māori population during this time was significant, increasing from 4903 in 1945 to 33,926 by 1966 which was 6.2 percent of the entire Auckland population.[10] Rural Māori immigrants also tended to congregate. By the 1960s, 43 percent of all Māori migrants to Auckland came to occupy South Auckland regions, while 15.4 percent of migrants occupied the inner city, proving itself to be the second most popular destination of Māori coming to Auckland.[11] As this Māori population grew, so too did the need for and value of a Centre.

Auckland Maori Community Centre. Permission from Bradley Wynn, “Research Report 111.540: Freemans Bay – The Form of a Community and its Urban Structure,” (Unpublished Thesis, University of Auckland, 1995), 44.

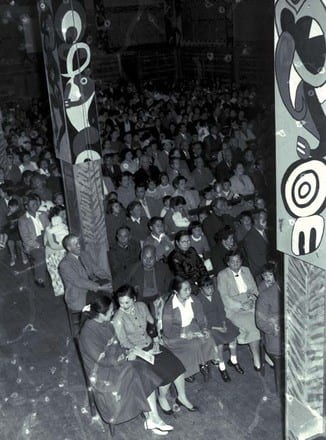

In parallel with the rising number of Māori in Auckland City was the emergence and growth of various Māori associations. As such, the Māori Community Centre became important in assisting and fostering a Māori urban community. Not only did the Centre serve the needs of the Trust Board, but for the first five years of its life the Centre was host to various weekend activities, being particularly popular among young Māori.[12] From Sunday Talent nights to weddings, the Centre was a place where Māori met, socialised, shared stories, and connected with other urban Māori.[13] The Centre developed into the most popular Māori meeting place in Auckland and was considered the epicentre for meetings and social gatherings.[14] There is also some evidence that the Centre was used by other ethnic communities in Auckland as a place to meet and socialise. For example, the photograph below shows Auckland’s Chinese community gathering at the Centre in the 1950s. It is likely that this meeting occurred in October of 1958 for the Double Tenth Celebration to commemorate the forming of the Chinese Republic in 1911. This photograph is also one of the few that show the interior of the Centre and the carvings that adorned the walls.[15]

Left to right, front row: Wailin Elliot née Hing, Eva Ng née Hing, Meilin Chong née Hing, Metin Tan née Hing, Mrs Hing and Jimmy Hing – all members of the Hing family (a longstanding Auckland family). Maori Community Centre, unknown photographer, 1950s, http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_library-photography-1140; the Hing family was identified by Rose Luey, email correspondence from Rose Luey to Author, 1 March 2019.

While the Centre became a hub of social activity, it is also from within its walls that many community outreach and support programmes were launched. For example, indoor basketball was well supported by the Centre as the Maori Youth Movement Indoor Basketball League held their annual winter competition in the Centre.[16]Additionally, this Indoor Basketball League also based its headquarters at the Centre under the leadership of members such as Mr Rautahi.[17] Moreover, various haka groups and youth clubs used its facilities, and much of the carving work that came to adorn Ōrākei Marae was completed at the tukutuku and carving schools set up within the Centre.[18] Even tangi, such as that of Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hiroa) were held at the Centre.[19] Indeed, the Centre facilitated the building of the Ōrākei Marae. As the esteemed kuia Ani Pihema recalled, facilitated by the Centre, “We could begin our carving project until the shell of the meeting house was completed and then we could return…The Marae was still a paddock at this time.”[20] The Māori Community Centre not only provided an important communal space for leisure and social gatherings but it also played a key role in fostering an urban Māori identity at a time when Māori in Auckland faced a series of political and social challenges. In this sense, leisure and resilience are both central themes intertwined in the narrative of this unique Auckland building.

*Kia ora, I whakapapa to Tuhoe and Nga Puhi.

Nicholas completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Auckland with a major in History and a minor in Art History, graduating in 2018. He went on to complete Honours in History, graduating with first class honours and in 2020 begun a Masters in Asian Studies at the University of Auckland. His project was focused upon fleshing out the social history of Auckland’s Maori Community Centre.

[1] Jenny Carlyon and Diana Morrow, Urban Village: The Story of Ponsonby, Freemans Bay and St Mary’s Bay (Random House, 2008), 249.

[2] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Village, 248; Map of City of Auckland and Environs – Proposed Boundaries of Community Centre Districts – Existing Maori Community Centre – Proposed ACC Community Centre – Existing School Halls – Existing Public Halls – Residential Areas – Existing Private Halls, 1947-1947, [Town Planning Plans], ACC 017, Item 6, Record 124 Record ID 502037, Auckland Council Archives.

[3] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Society, 248; C. M. Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” (Unpublished Thesis, University of Auckland, 1983), 39.

[4] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Village, 248.

[5] Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” 39

[6] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Village, 248; Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” 39

[7] Map of City of Auckland and Environs, ACC 017, Item 6, Record 124 Record ID 502037, Auckland Council Archives.

[8] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Village, 249.

[9] A study of the Orakei Marae Centre by Pauline Kingi, March 1992, NZMS 843, Box Orakei Marae Trust Board, Margaret Boyce, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland City Library, 26.

[10] Ian Pool, “Maoris in Auckland: a population study,” The Journal of the Polynesian Society (1961); 47-49; Donald Trevor Rowland, “Maori Migration to Auckland,” New Zealand Geographer 27, no. 1 (1971): 30.

[11] Rowland, “Maori Migration,” 30.

[12] Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” 40.

[13] Joan Metge, A New Maori Migration: Rural and Urban Relations in Northern New Zealand (London: Athlone Press, 1964), 185.

[14] Kelly, “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society,” 40.

[15] Email correspondence from Rose Luey to Author, 1 March 2019. The catalogue details for the photograph state it was created on 13th October 1958 see http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_library-photography-1140

[16] Jock Taua, “The Auckland Maori In Sport,” Te Ao Hou, June 1959: 71.

[17] Ibid, 71.

[18] Carlyon and Morrow, Urban Village, 249.

[19] Ian Pool and Tahu Kukutai, “Taupori Māori – Māori population change – Post-war changes, 1945–1970,” Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/taupori-maori-maori-population-change/page-4 (accessed 28 January 2019)

[20] A study of the Orakei Marae Centre by Pauline Kingi, March 1992, NZMS 843, Box Orakei Marae Trust Board, Margaret Boyce. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland City Library, New Zealand.