Part Two

Female Perspectives and Female Issues: Different approaches to politics

Part Three

Two Powerful Voices in Diverse Communities

by Brooke Stevenson*

Mere Newton, local Māori politician and social worker, and Mary Dreaver, a daughter of Scottish immigrants and a national politician, operated within their vastly different spheres of influence in 1937. However, Newton and Dreaver’s isolated worlds merged on the 12th June 1937 when Mere Newton invited Mary Dreaver to become a guest speaker to the ladies’ social committee of the Epsom-Oak branch of the Labour Party. As the local press explained, after ‘community singing’, Dreaver took her place as guest speaker and spoke about ‘New Zealand movements of interest to women for building a new social order’.[1] This is an excellent example of both Newton and Dreaver’s style of politics, from Newton’s utilising social connections and organising events to further causes, to Dreaver using her oration skills as a way to further her political agenda.

Promoting Issues within the Female Sphere

In her capacity as secretary of the social committee of the Epsom-Oak branch of the Labour Party, Mere Newton presided over an attendance of women each Saturday in a lecture series that predominantly focused on discussion and education of issues that, at the time, affected the lives of women and children.

The Auckland Star journalist who reported on Dreaver’s lecture commented on Newton’s desire to develop the social side of the branch work and to connect and build relationships between Labour Party female members. The journalist predicted this would be the forerunner of “many pleasant and instructive gatherings.” The reporter was correct in this prediction. This very first social afternoon organised by Newton was one of many at the branch office on the corner of Manukau and Mt Albert Rd, where women would convene to discuss pressing social issues brought forward by an array of guest speakers.

On that 12th June 1937 afternoon, Dreaver’s large range of topics that she spoke on included reporting on the good work of the Young Mothers’ Club, which provided help and advice for ante and post-natal care, the aim of the Labour Government to give every mother, married or unmarried, full maternity benefits and assistance, and celebrating the initiative of the Labour Government to extend the widow’s pension to deserted wives.[2]

The afternoons in the following weeks reportedly included a strategic combination of political discussion and social entertainment. An array of lecturers were invited to speak upon issues such as female involvement in politics, maternal health issues and the art of raising children. Newton also directed an afternoon of impromptu debates which included ‘wit and wisdom’ from the female debaters.[3]

A collection of headlines from local newspapers detailing the activities of the social committee of the Epsom-Oak branch of the Labour government.

Guest speakers in 1937 included Marion Hurst who “traced how women through the ages had climbed from a position of oppression and slavery to intellectual and political freedom”, realizing the economic power of women as consumers representing the home.[4] R. Wynn, secretary of the Auckland women’s branch of the Labour Party, spoke of encouraging women to enter Labour politics as a way to contribute to “social reorganization”.[5] Alice J. Greville spoke about child rearing and the value of children in society, and promoted the idea of fostering creativity in children as highly important to development.[6] Māori women were also referenced in a number of speeches, from recognizing the need for universal motherhood endowment for Māori families, to commemorating the sacrifices and hard work of Māori women in earlier days.[7] The varying topics and popularity of these afternoons show the political agency of women of this time, and the willingness and belief that these women had a lot to contribute to their community because of the simple fact that they were women.

In researching the way women interweaved political campaigning and relationship building through social events during this period, it is clear that Newton was an effective and excellent facilitator. This provided another platform for women such as Dreaver to exert her charisma and public speaking skills to advance various political agendas. Through these different practices, Dreaver and Newton sparked conversations and ignited change over issues predominantly concerning women that may not have received such levels of attention in more traditional political spaces.

A Feminine Perspective

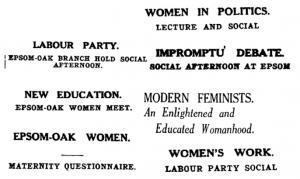

In addition to promoting causes relating to women, both Newton and Dreaver managed to promote a female perspective on societal issues. The Tamaki Māori Women’s Welfare League was founded in 1930 by Newton, her daughter Delia and Chieftainess Te Paea. The central purpose of the League was to protect the interests of the Māori race, primarily Māori women, through furthering knowledge of Māori history, customs, music and language, and it was reported that all the meetings would be conducted in the Māori language.[8]

A snippet from an article about the Tamaki Maori Women’s Welfare League ‘Māori Women’s League’ New Zealand Herald, Volume LXVII, Issue, 20622, 22 July 1930.

Through her capacity as founder of this branch, Newton brought forth a female perspective of the issue of the Māngere housing crisis, where she is seen to be especially concerned with the safety and education of Māori children.

In an interview with the Auckland Star, Newton recounted her experiences visiting Māngere and particularly focused on the plight of the Māori children she saw:

“When I visited the place, I found a seven year old girl sits in out in the garden from before 6 o clock in the morning until it is time to go to school, pulling a string attached to kerosene tines to frighten the birds away. She is relieved by the elder sister until school is over, where the younger one takes her place until nightfall”[9].

Newton also reported that there was another boy of school age who could not attend because he had no clothes, and another who did attend but with no lunch.[10]

Dreaver too brought a female perspective to issues in parliament. As the third woman to enter parliament, Dreaver often incorporated novel stories and thought processes into her reasoning within her parliamentary speeches and debates. In her very first speech in parliament she made a point to incorporate her experience as a woman into the debate of the Social Welfare Bill currently making its way though parliament:

“It has often been said that the making of laws is a job for men only and that women should keep to their homes. I know many men have had that thought in their minds for generations, applauding masculine politics when they were good and keeping discreet silence when they were bad. My presence here is an answer to that. I feel I have the good will of many women in New Zealand, as well as that of the people in my own electorate, and I venture to add that the economic experience of women in the homes provides the best reason for their taking a parliamentary part in the shaping of what I would call “domestic legislation”, which is so important today”.[11]

This began a common theme of Dreaver incorporating the female experience into a multitude of topics. She applauded the new amenities given to New Zealand miners and emphasised the follow-on effect of providing miners’ daughters with the structures to enter better professions, such as nursing.[12] In addition to this, whilst speaking on the issue of repatriation of New Zealand soldiers, Dreaver urged the MPs to look at the perspective from a female point of view.

“Every New Zealand woman who had a man in the war of 1914-18, every New Zealand woman who had a son in this war or a girl overseas, cannot but take an interest in repatriation.”

Dreaver commented on the needs of the wives of men coming back from war, from being provided monetary support to furnish state housing, to the government providing a system of lowering rent so young adults were able to afford to support a family.[13]

Dreaver and Newton both exemplified a feminine approach to politics that does not fit within the mainstream political system that was dominated by men. Through working within the current system, dominating the political arena with speeches presenting the female perspective, or creating platforms and networking to create a space of awareness of feminine political issues, these two women showed varying approaches towards a female orientated “social reorganisation”.

This is the second article in a three part series. To read article three.

* Brooke was one of four students awarded a 2020 Summer Scholarship at the University of Auckland out of a highly competitive field. Her award was funded by a Jonathon and Mary Mason Scholarship in Auckland history. Brooke’s research project explored women in Auckland politics. She focused her efforts on two women, studying the motivations, methods and achievements of Mary Dreaver and Mere Newton.

[1] Labour Party’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVIII, Issue 140, 15 June 1937.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Impromptu Debate’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 172, 22 July 1937.

[4] ‘Modern Feminists’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVIII, Issue 146, 22 June 1937.

[5] ‘Women’s Work’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 160, 8 July 1937.

[6] ‘The Problem of Childhood’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVIII, Issue 152, 29 June 1937.

[7] Ibid., ‘Epsom-oak Women’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVIII, Issue 205, 30 August 1937.

[8] ‘Māori Women’s League’ New Zealand Herald, Volume LXVII, Issue, 20622, 22 July 1930.

[9] ‘Welfare of Māoris’, Northern Advocate, 14 August 1931.

[10] Destitution of Māoris’ Auckland Star, Volume LXII, Issue 186, 8 August 1931.

[11] Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust, (7th August 1941), Finance Bill, p25.

[12] Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust (30th July 1943), Supply, p. 425.

[13] Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust, (16th October 1942) Rehabilitation Bill, p. 1184.