Part One

The Standing Point: Studying the History of Auckland’s Chinese People

Oct 27, 2020

by Hanna Lu*

History is not about us. I mean, the people involved are usually not us. But the stories we tell are about ourselves, and who we’ve been, and what we mean when we say ‘ourselves’. Are there concepts of who we are that rest on the exclusion of certain groups? If our sense of expansiveness is to change, our approach to history must change with it but the process is complex. This article is about that complexity.

The subject: Chinese history in Auckland, an under-explored area. My initial notes were full of ambition — I wanted to reinsert them into history and emphasise diversity and bring out a presence that had been pushed to one side. I was confident because I had something special working in my favour: a collection of interviews with early settler families, yet unstudied.

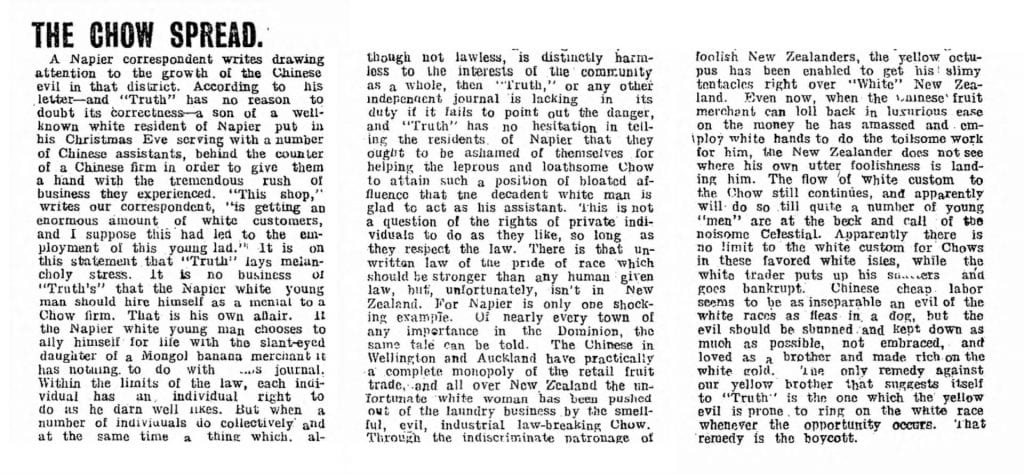

Existing resources certainly showed a need for a different perspective. Negative feeling against Chinese people left no lack of evidence: an 1879 petition by the Auckland Workingmen’s Club with the (unverified) accusation that Chinese workers were harming good citizens by accepting lower wages, signed by 3000 people; multiple mentions in newspapers of “immorality”; a 1910 article in the New Zealand Truth that talked about “the leprous and loathsome Chow” and “the yellow octopus” that had its “slimy tentacles right over “White” New Zealand”.[1] The New Zealand Truth in particular was responsible for publishing the most and the worst of it.

We know that the most extreme are often the loudest, but thankfully in this case, voices were raised in opposition to the vitriol. The Auckland Women’s Political League declared in 1896 that they “would never vote for keeping the Chinese out”; the Kaipara and Waitemata Echo in 1912 wondered if “China-phobes” knew that it was “we, the good old irreproachable British” who “invaded their country”; and the 1914 Maoriland Worker advocated solidarity with the Chinese against those who would “impartially rob the workers of all nations”.[2]

You may have noticed that Chinese people themselves are not present at all in this dialogue.

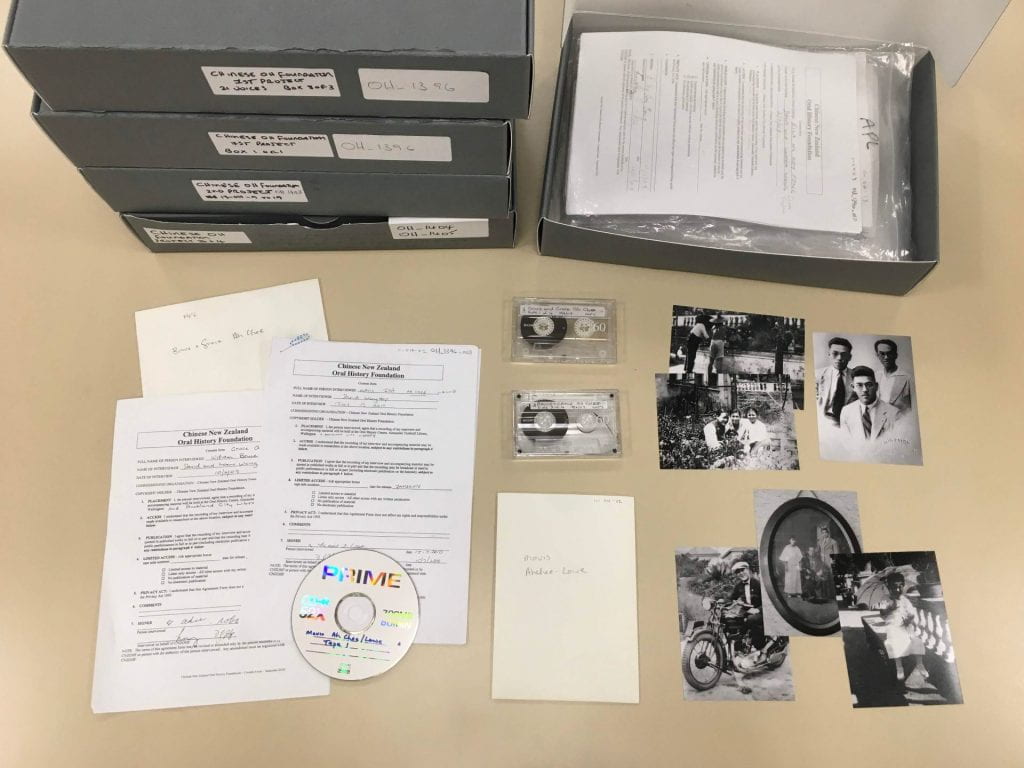

Enter the Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation. With materials funded by the Chinese Poll Tax Heritage Trust,[3] the Auckland City Community Organisations Grant Scheme, and the Sky City Auckland Community Trust, the Oral History Foundation conducted interviews with the descendants of those who paid the poll tax (in place from 1881 to 1944, a hundred pounds at its highest in 1896 and applying only to Chinese arrivals), and this project draws on the fourteen of them that are based in Auckland.[4]

Much of the interview content aligns with what has already been written about Chinese settlers in Auckland. They were market gardeners, fruiterers and laundry-people because of the industries’ low starting costs, structure of self-employment and need for only basic English. They contributed to World War Two efforts by feeding the troops.[5] Their lives were centred around the family business: Ella Hoy Fong (née Wong) recounts her job in the garden guiding the horse and plough, doing everything by hand, working for two to three hours after school and all weekend and all through the holidays — giving us a better appreciation of the effort it took from all members of the family to keep the business running, and pointing to a reason why Chinese people were seen as keeping to themselves.[6] Willie Wong details his family’s procurement and use of manure, blood and bone, while Wong-Yee Chan describes seeds and their varieties — demonstrating that pure intellectuals were not the only ones doing work that involved knowledge and skill.[7]

Horse and plough, 1969, print, Footprints Collection 07712 Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, Auckland.

But how about my hopes of changing the writing of history? When were they going to talk about politics and ideals and how important they were? It is obvious that they had a part in Auckland society and got on with their lives, but what were their thoughts about it?

As it turns out, there was more to be looking for.

Chinese people’s place in Auckland — shaped, for the most part, by experiences of discrimination — was not a topic that the interviewees liked to talk about. Mentions of it were dropped in passing, or it is implied, and moved on from quickly. Legislation affected their families and life decisions: David Wong Hop left school at age fifteen to work full-time in the shop because Chinese immigration laws made it difficult to find workers, and his sister Joana F Sang (née Wong) observed that uncle Charlie had to run his laundry shop by himself because he couldn’t get his family out from China.[8] Most accounts are interpersonal: Joyce Khoo and Cheryl Num’s family made sure to dress well and their father protected his smaller friend from discrimination at work; Wah Ying Chau says her son didn’t realise he was different until someone at school pointed to his skin and said “you’re not gonna wash that off”; and Willie Wong explains that the Chinese gardeners avoided a certain market because when they turned their backs, their produce would be thrown on the ground by people telling them that they should not have been there.[9] Their narration is pragmatic and unemotional. They don’t dwell.

Willie Wong: If you ever got stuck and needed a bit of money, you’d go down to Donalds and they’d give you some money, to keep you going. Turners only looked after their own people, the European growers that went to Turners, they had hardly any vegetable growers there, although the only green vegetable grower was Franklin, he grew a lot of celery and that was about it. And you had the Europeans growing pumpkins, potatoes, onions, all that stuff but they didn’t have much green. In those days Donalds controlled the whole lot. They had all the greens. The Chinese, they wouldn’t go there, because the, [laughs] they knew what was going on. If you had put your stuff out where the Franklins had their celery, by the time you turned your back around that’d be all on the ground. Just took them off and threw them all away. You’re not supposed to be there. So who’s gonna be a Chinese and put stuff there?[10]

Much more time is devoted to talk about movies, dancing, and racing, and in the flow of conversation these are the easiest and chattiest topics with the brightest tones.[11] Perhaps this is because they were interviewed by a peer who understood their experiences, with whom they wanted to reminisce.

Or perhaps their glossing over experiences of racism means that it didn’t affect them that much, and the newspapers are just exaggerating? Not quite.

The interviewees knew that what they said would have an impact, on those who would listen and on themselves as they said it. Maybe they didn’t want to be remembered only as victims of racism, or maybe they thought of discrimination as just another thing that they had to deal with. They talked about their work and leisure because of a pride in their own success, backgrounded by struggle. It was not a sign that everything was peachy.

Joyce and Cheryl’s interview extract has a similar pragmatic tone to Willie’s, but they are a generation younger and are interviewed five years later, in 2014.[12] More Chinese people came to Auckland as they grew up, and the conversation around Auckland Chinese history and culture has developed especially in the last ten years. Discussing their father’s exposure to discrimination, they were more explicit in their description of the injustice.[13]

Charles: What kind of discrimination did he face?

Cheryl: Well, originally he was from the era of the plait, the long hair, so the first thing he did was cut it off. Then he dressed himself like a gentleman, always had a hat, so all the children were very, very well dressed. Y’know, and the discrimination was more, they expected them to not be intelligent, really.

Joyce: I still remember Dad saying that when he worked in the railways, he had to look after another very good friend. People were picking on him, I think he, uh, he punched them. [Laughs] Cause they were just, yeah, to stick up, because he was a little fella, and my Dad was a bigger guy, and they were being really bad, horrible, to my Dad’s friend.

Charles: So what did Dad do?

Cheryl: I think he punched someone. To stick up for him because they were about to abuse Mr Fong! Little Mr Fong, in those days.[14]

This is the most that any of them ever say about the issue of racism. Underlying these comments is the sense that the expected emotion from Chinese people is thankfulness in general, and gratitude that they were seen as a model minority — at least that is a positive thing. In an article from the 14th of May 1975, published in the Auckland Star, Dr. Gam Lee communicates that children are taught good values, and to “maintain the respect others have developed for the Chinese community over several generations”.[15] He knew that as a minority, any action that a Chinese person took would represent not just themselves, but the whole group. Respect (of a sort) was given to them, but it had come through effort and needed to be held onto — it was something precarious that could be taken away.

Chinese people’s place in Auckland was a concern because it had to be, but mostly, they just strove for an opportunity to live their lives the way they wanted.

In the light of these stories, the broad goal of representing minority experiences becomes something harder to achieve. Everything was affected by specifics: age, which casted a pleasant light over childhood memories; trauma, which functioned in their lives in different ways; and the different years and places and families into which they were born.

The Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation collections at the Sir George Grey Special Collections, taken by the author.

What we can learn from this oral history collection in its days’ worth of audio is what it truly means to step into another’s shoes. We can dream about creating complete and inclusive accounts, but we cannot assume that there is simply some other, duplicate history running in parallel to the ‘mainstream’, and that all we need to do is reach out. Minority histories are shaped by their context — the way that these historical actors chose to carry out their lives, what they recorded about it, and the way that they speak about it in hindsight are all contained within the bounds of what was required for survival. Through interviews and evidence we learn about their lives, but we also see that their story changes our existing one. It demands a recognition of consequences and assumptions, going beyond incorporation and towards re-centering.

* Hanna was one of four students awarded a 2020 Summer Scholarship out of a highly competitive field. Her project focused on a group of Chinese families in Auckland in the twentieth century and she describes this topic as a timely one. As we grapple with the urgent need for ethnic diversity in history, this research highlights moments of grace in Auckland’s past, and suggests a reorientation in the way we write about ethnicity and what Auckland has been to its people.

[1] Charles P. Sedgwick, “The Politics of Survival: A Social History of the Chinese in New Zealand,” (PhD diss., University of Canterbury, 1982), 175; “The Chinese Question.” Observer, May 16, 1896; “The Chow Spread.” NZ Truth, January 1, 1910.

[2] “The Chinese Question.” Observer, May 16, 1896; “Mokai.” Kaipara and Waitemata Echo, December 11, 1912; “Yellow Peril Liars.” Maoriland Worker, January 7, 1914.

[3] Established in 2004 as part of a formal apology to the Chinese community for the series of discriminatory legislation put in place from 1881 (and then gradually abolished from the mid-twentieth century).

[4] David Wong, email correspondence with author, April 10, 2020.

[5] Joanna Boileau, Starch Work Done by Experts: Chinese Laundries in Aotearoa New Zealand (Wellington: Chinese Poll Tax Heritage Trust, 2019), 27-8; Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, August 20, 2009, and September 6, 2009, audio; Ella Hoy Fong (née Wong), interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, July 2, 2009, audio.

[6] Ella Hoy Fong, interview.

[7] Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview; Wong-Yee Chan, interview by David Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, July 21, 2011, audio.

[8]David V Wong Hop, interview; Joana F Sang, interview.

[9] Joyce Khoo and Cheryl Num, interview by Charles Chan, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 4th Project, September 27, 2014, audio; Wah Ying Chau (Chong), interview by Charles Chan, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 4th Project, July 21, 2015, audio; Willie Wong, interview.

[10] Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview.

[11] Wilie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview; Ella Hoy Fong, interview; Joyce Khoo and Cheryl Num, interview; Mavis Lowe (née Ah Chee), interview by David Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, July 15, 2010, audio; May Sai-Louie, interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, October 23, 2007, audio; David V Wong Hop, interview by Edwin Welch, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, August 22, 2011, audio; Joana F Sang (née Wong Hop), interview by Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, January 19, 2012, audio; Wong-Yee Chan, interview.

[12] Joyce Khoo and Cheryl Num, interview.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Centre Will Keep Chinese Unity.” Auckland Star, May 14, 1975.