Part Two

Bersatu Dan Maju: Malaysian International Students as a Rising Political Force

by Laura Prahash*

Negaraku My Motherland

Tanah tumpahnya darahku, For whom I spill my blood,

Rakyat hidup, The people live,

Bersatu dan maju! United and progressive![1]

Two decades after the first international students arrived in Auckland, there was a bustling international student community established at the University of Auckland. Between 1965 and 1969, the number of students had increased more than twofold, largely due to government-funded aid schemes.[2] However, by the late 1960s, wider social unrest was echoed within the international student community in Auckland as the relationship between these students and their host city shifted from cultural to increasingly political exchanges.

The international student body became a rising political force, one that compelled the Government to take action. This was most clearly seen amongst Malaysian students in Auckland. Using these students in the 1970s as a case study, we shall see how repression and student protests in Malaysia and New Zealand led to the imposition of a quota and a fee hike, which students then organised against in response.

In 1970, 40 percent of international students at the University of Auckland were from Malaysia.[3] But between 1976 and 1981, the number of Malaysian students decreased by almost 50 percent.[4] This can be attributed to the imposition of a quota on the number of incoming Malaysian students, an increase in fees, and allegations of spying and marriages of conveniences. It was the introduction of these discriminatory policies that would lead these Malaysian international students to assert their right to be here in Auckland, and to make sure New Zealanders knew that their presence, although temporary, was one that deserved recognition as contributing members of the central Auckland community.

The majority of overseas students in Auckland during the 1950s were aided by the Colombo Plan or other bilateral aid schemes. Yet, by the late 1960s, this was inverted, with 71% of all international students being privately funded by 1970.[5] The majority of these students hailed from Malaysia, which was undergoing a period of massive political and social upheaval.

There were very few universities in Malaysia at that time, and those that did exist had quotas set aside for Bumiputera (Malay and Indigenous) students, quotas which were introduced due to recent racial riots. For many ethnic Chinese, this meant that they had to go overseas in the pursuit of further education. In fact, there were more Malaysians studying in overseas tertiary institutions than in Malaysia.[6] Qualifications obtained overseas were also viewed in higher regard. The first female Engineering graduate from the University of Auckland, Gee-Ing Yeow, was a Malaysian international student.[7] She said that a big factor in her choice to study here was because a degree from the University of Auckland would be recognised globally, unlike a degree from Malaysia.[8]

A picture of Gee-Ing Yeow, the first female Engineering graduate from the University of Auckland[9]

Yeow was one of hundreds of Malaysian students on campus, many of whom were affiliated with the Auckland Malaysian-Singaporean Students Association (AMSSA). Prior to the mid-1970s, they were largely a social club: which organised sports games, movie nights, camps and forums. But two developments would slash the number of Malaysian students, forcing AMSSA to step into a new phase of advocacy. The first of these was a quota which aimed specifically to limit the number of Malaysians studying in New Zealand.

40 Percent

The AMSSA first heard about the quota in October 1976 when the Minister of Immigration, Frank Gill, officially announced that there would be a 40% limit on the number of private students from any one country, and that entry from the Middle East would now be allowed. Gill alleged that this was due to increased participation from a wider number of countries, especially those in the South Pacific and the Middle East.[10] Despite his claims, the following year only saw an increase in three South Pacific students, and no students from the Middle East.[11]

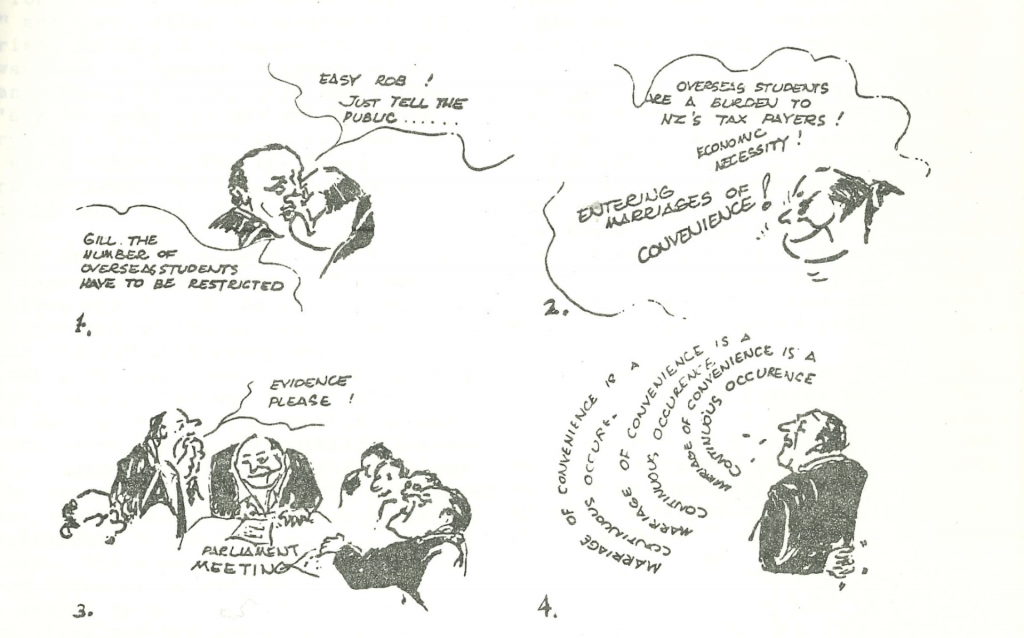

Another political intervention included the tightening of restrictions for permanent residency, including a two-year probationary period on marriages between overseas students and New Zealanders. Gill justified this change by insisting that Malaysian students were frequently getting “marriages of conveniences” in order to secure permanent residency. When questioned about where his evidence was, he refused to offer any.[12]

A cartoon from SUARA (a publication produced by AMSSA) illustrating how a student interpreted the claims Mr Gill was making about marriages of inconvenience and then his refusal to show evidence.[13]

Why Malaysian Students?

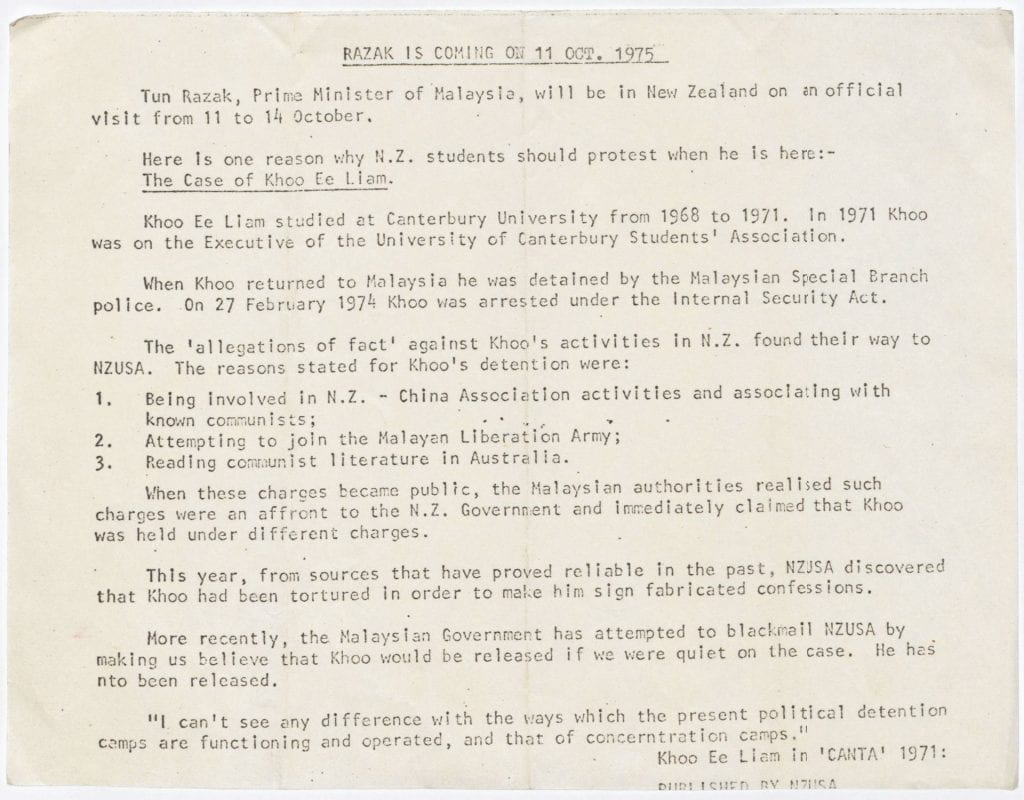

Student activists in Malaysia in the early 1970s posed a threat to the Malaysian Government as they actively spoke out against repression and protested. As a result, the Government passed the Malaysian Universities and University Colleges (Amendment) Act of 1975. This meant that no one affiliated with a tertiary institution, whether staff or student, could engage with any political activity, otherwise they would be expelled, arrested, and could be imprisoned without a trial or tortured.[14] In response to this repressive Act, there were protests within Malaysia, as well as by Malaysians in Australia, the UK, and New Zealand, demanding the release of these students. One way the Malaysian government responded to these growing political protests was through initiating talks between New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Norman Kirk, and Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Abdul Razak, in 1972.[15]

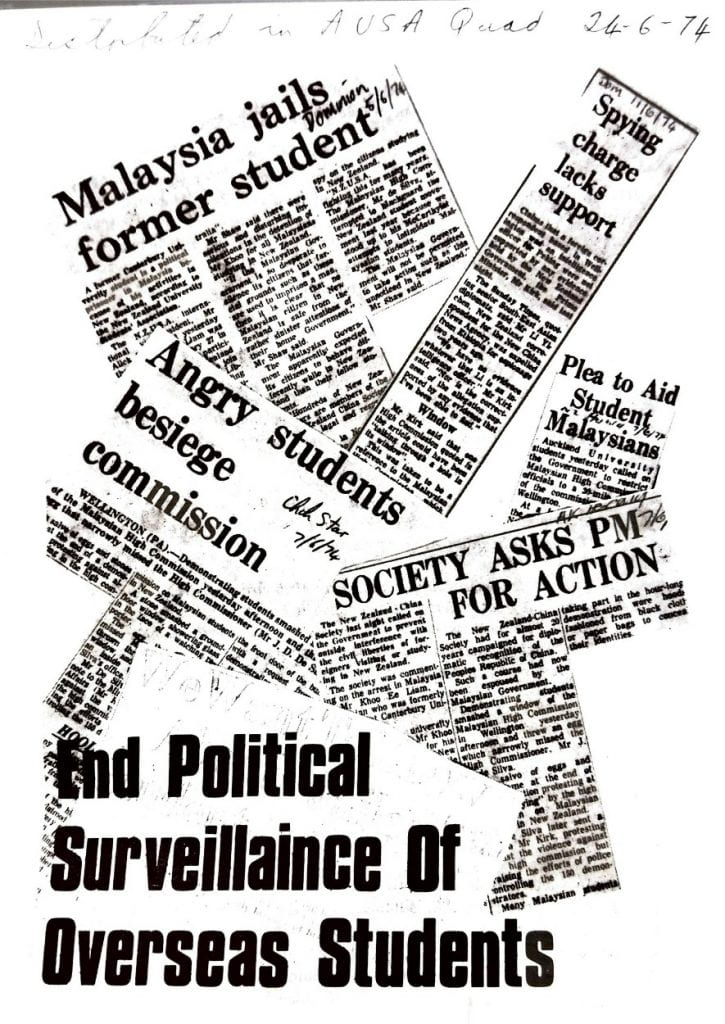

The following year, the Malaysian High Commissioner, Mr Jack de Silva, alleged that Malaysian students in New Zealand were being ‘subverted with Communist propaganda’.[16] Although this allegation was refuted by both Kirk and Razak, who said there was no evidence for those claims, it raised suspicions that Malaysian students abroad were having their actions monitored. These events came to a head when a student returned from his time studying in New Zealand only to be arrested in Malaysia for being politically involved in New Zealand.[17] Malaysian international students worldwide were outraged. This confirmed that they were being monitored, and that their government was prosecuting students for actions taken legally in New Zealand. The AUSA president called for NZUSA to question the government about the use of New Zealand Secret Services to monitor Malaysian students.[18]

A pamphlet titled “End Political Surveillance Of Overseas Students”, with -“distributed on AUSA quad 24-6-74” handwritten on the top in pencil by the History Professor who collected it, Michael Stenson. Inside the pamphlet was information about Khoo Ee Liam (the student who was arrested), and the intimidation of students by the Malaysian government.[19]

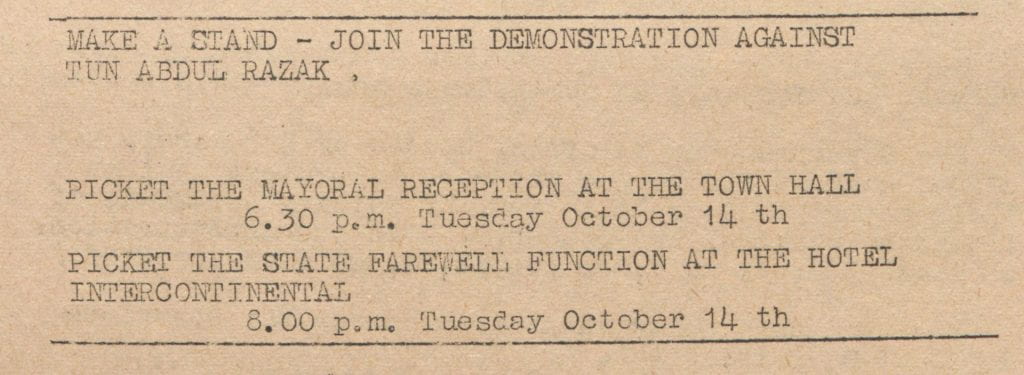

When Razak toured New Zealand in late 1975, he was met with student demonstrations in Auckland, and handed a petition. The AUSA president read the demands of the students, expressing solidarity with the cause of the Malaysian students.[20]

Two examples of pamphlets that were distributed in Auckland when Malaysian PM, Tun Abdul Razak, came to visit in 1975.[21]

Immediately following Razak’s visit, the two governments began corresponding about restricting numbers of students coming to New Zealand.[22] This appears to be no coincidence. It appears that the New Zealand government instituted the cutback to appease concerns the Malaysian government had about its overseas students protesting its regime.[23]

The government’s interference toward suppressing political activity impacted campus life beyond these instances of protesting. The Malaysian High Commission told Malaysian students at the University of Auckland to form a Malaysian Students Association separate from the AMSSA, which would allow them to have a tighter rein on the students’ behaviour. Despite an overwhelming majority voting against this formation, it proceeded and was officially recognised by the Malaysian High Commission.[24] In fact, the University of Auckland was the only main hub in New Zealand that retained a separate Malaysian Singapore Students Association despite pressure from the Malaysian High Commission.[25] AUSA continued to officially recognise “the AMSSA as representing Malaysian students in Auckland,” and banned AMSA from the use of student amenities altogether.[26] The secretary from the AMSA suggests that AUSA refused to recognise the AMSA because that would involve challenging the AMSSA, whom they were closely affiliated with.[27] Publications by both groups revealed much distaste for the other. Not even their shared identity as Malaysians was enough to bridge the growing rift.

Malaysian students were very aware that the socioeconomic and political situation back home was behind these changes, and made this clear in their student publications.[28] While it was financially risky for New Zealand to be so dependent on a single country for international student income, it became clear that a quota and the later imposition of a fee was just another way to ensure that fewer Malaysians were making it to our shores. Read more about this in my third article

Semua Kita Berseru (Let Our Voices Soar as One)[29]

AMSSA took action. Along with several other international student clubs at the University of Auckland, they formed the Auckland Overseas Students Action Committee (AOSAC), a standing committee in AUSA. Allied with NOSAC, the National Overseas Students Action Committee, they initiated a campaign that led to a national conference of Malaysian students. An action week was held on campus from 18-23 July 1977, with events such as forums, meetings, and a cultural evening.[30] The final event was a rally organised by AUSA and AOSAC on July 26th, the day before the Overseas Students Admission Committee (OSAC) AGM, and similar rallies were held simultaneously at every other campus nationwide.[31]

OSAC unanimously voted the following day at their 1977 AGM to recommend the quota be dropped.[32] The Auckland University Council also condemned the cutbacks, recognising the contribution of Malaysian students to New Zealand, and calling for consultation between the Government and universities.[33] It appeared that both OSAC and the University Council had not been consulted about the cutbacks at all.[34]

As a direct result of the cutback, the total number of first-year undergraduate Malaysian students at Auckland University decreased from 90 in 1976 to 56 in 1977.[35] Across the nation, the number of private first-year undergraduate students that came directly from Malaysia decreased by over 75% in just one year.[36]

Even though ultimately the quota was still enforced, these student actions demonstrate a marked shift in how international students saw themselves as part of New Zealand, Auckland, and the University of Auckland student body. The Anti-Cutbacks Campaign was possibly the first New Zealand political campaign led by overseas students.[37] AMSSA was acknowledged by AUSA for contributing to life on campus beyond their intended cultural and social role, but in particular as a political organisation.[38]

Once thought of as on the fringes, these Malaysian students demanded treatment as educational equals to other Auckland and New Zealand students. As an article published in Suara at the start of the year expressed, “just because you are temporarily living in N.Z. you don’t have to feel you cannot make searching comments about N.Z. society.”[39] Although their time here may have been relatively brief, these students undoubtedly left an impact on Auckland. But there was a bigger hurdle soon to come: the imposition of a 750% fee hike for all international students.

[1]This is the Malaysian national anthem, Negaraku, translation and lyrics from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negaraku

[2]‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics 1965, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1966, U16; ‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics 1969, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1970, U16.

[3]‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics 1970, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1971, U16.

[4]‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics 1976, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1977, U16; ‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics 1981, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1982, U16.

[5]Nicholas Tarling, International Students in New Zealand: The Making of Policy since 1950, Auckland, New Zealand: New Zealand Asia Institute, University of Auckland, 2004, 35.

[6]Suara, 4, no.3 (1979), 2.

[7]‘First Woman Engineer’, New Zealand Herald, 9 December 1969.

[8]‘First Woman Engineer’

[9]‘First Woman Engineer’

[10]‘Overseas Students’ Cutbacks Campaign’, 29 July 1977, Socialist Action League records. 1970-1979. MSS & Archives A-209, File 3/519. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[11]‘Overseas Students’ Cutbacks Campaign’

[12]‘Overseas Students’ Cutbacks Campaign’

[13]Suara, June-July (1978), 4.

[14]‘University and University Colleges Amendment Act’, Michael Stenson papers. ca. 1968-1977. MSS & Archives A-189, Series B, File B/5.Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services; ‘Malaysia-Singapore Supplement’, William Broughton literary research papers., MSS & Archives 2014/05, Series 1, File 1/162h. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[15]Salient, 4 October 1976.

[16]‘End Political Surveillance of Overseas Students’, Michael Stenson papers. ca. 1968-1977. MSS & Archives A-189, Series B, File B/4. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[17]‘End Political Surveillance of Overseas Students’

[18]‘Solidarity! For Khoo, Against Coup’, Craccum, 48, no. 13 (1974),1.

[19]‘End Political Surveillance of Overseas Students’

[20]‘The Trail of a Prime Minister’, Socialist Action League records. 1970-1979. MSS & Archives A-209, File 3/522. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[21]Michael Stenson papers. ca. 1968-1977. MSS & Archives A-189, Series B, File B/4.Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[22]‘Malaysian Students Cutback Conference Background Paper – Christchurch 1976’, Socialist Action League records. 1970-1979. MSS & Archives A-209, File 3/522. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services

[23]‘University quota cuts cause stir’, Auckland Star, 16 February 1977.

[24]‘End Political Surveillance of Overseas Students’, Michael Stenson papers. ca. 1968-1977. MSS & Archives A-189. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[25]‘Malaysian Government Interferes at Auckland University’, Craccum, 42, 10 (1969), 3.

[26]‘The Auckland Malaysian-Singapore Students (AMSSA) Statement: WHY AMSA IS NOT APPICIATED (sic.)’, Socialist Action League records. 1970-1979. MSS & Archives A-209, File 3/522. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[27]MSA Secretary, ‘The MSA Challenge and Response’, in Malaysian Evening, 3rd Sept. 1971: Souvenir Programme, University of Auckland Malaysian Students Association, 1971, 16.

[28]‘Our Message’, Suara, 2, no. 4 (1977), 3.

[29]This is a quote from the Singaporean national anthem, Majulah Singapura, translation taken from the official Government translation at https://www.nhb.gov.sg/what-we-do/our-work/community-engagement/education/resources/national-symbols/national-anthem

[30]‘Go All Out (Action Week Program)’, Suara, 2, no. 3 (1977), 4.

[31]‘Go All Out’

[32]‘Our Message’, Suara, 2, no. 4 (1977), 3.

[33]‘Consultation Wanted’, New Zealand Herald, 19 July 1977.

[34]‘Students to Protest at Cut in ‘Outside’ Places’, Evening Post, 25 May 1977.

[35]‘ISHI Report of Secretary’, May 1977, New Zealand Federation of University Women, Auckland Branch further records. MSS & Archives 2011/01. Series 7. File 7/84. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[36]‘ISHI Report of Secretary’

[37]‘Our Message’

[38]‘Message from AUSA President’, Suara, 2, no. 1 (1977), 5.

[39]‘Message for 1977’, Suara, 2, no. 1 (1977), 3.