Part Three

A Rift Down Hobson Street: The Yugoslav Clubs and Political Debate

by Helena Wiseman*

The two Yugoslav Clubs in Auckland were divided by more than just the road on Hobson Street. Immediately after the war they had worked together to support their community, and many Dalmatians frequented both locations. But at the highest levels of the organisations, political tensions simmered. The disagreements that ensued were fundamentally Yugoslav in nature, but played out in Auckland city, where they captured attention beyond the Dalmatian community.

In 1947, Tito’s Yugoslav Consul visited New Zealand. One club, the Benevolent Society, chose to host his visit; the other, the Yugoslav Club, decried it as too political. A fault line that had long existed in the community finally gave way. On 15 October 1947, the Northern Advocate ran a piece headlined “Auckland Yugoslavs Split into Factions”.[1] The paper – read widely in Auckland society – then detailed the fundamental debates within the Dalmatian community.

The article tells us that wider Auckland was interested in the political lives of their Dalmatian immigrants. The interest makes sense in the context of 1947: Yugoslavia was by that time a communist state, and the Cold War was beginning to take hold.[2] Given that context, and post-war suspicion that once again afflicted a Dalmatian community, the question becomes to what extent the ‘split’ in the Yugoslav community was sensationalised by Auckland media, and if so what form this moment in Auckland Dalmatian history actually took.[3] The answers require an examination of activities of the clubs from 1947 through the 1950s.

According to the Northern Advocate, the essence of the factionalism was that “members of the Yugoslav Club have refused to share in the activities of the politically-minded Yugoslav Society Marshall Tito [the Yugoslav Benevolent Society]”. The paper reported that members of the Yugoslav Club regarded the Society Marshall Tito as “a thinly veiled communist organisation”, which was a charged allegation in 1947.[4]

The Society Marshall Tito or Benevolent Society’s members perceived themselves as from a certain class of the Auckland Dalmatian community. Tony Barbarich, who joined the club in 1948 amidst this very disagreement, characterised his club as “working class”, as contrasted with the “rich orchardists” at the Yugoslav Club. He called that divide a “faction”, and so we know that the community itself did perceive a political break, and feel some sense of disconnect between the two societies.[5]

We can also look to the activities of the clubs and see clearly the political divide. The correspondence of the Yugoslav Club includes several letters to political organisations that had reached out to the club to collaborate, rejecting those offers on the grounds that the club did not engage with political matters. In 1946, the club’s secretary replied to Mrs A.M. Cassie of an unnamed political party, who had written to ask for sponsorship and use of the clubrooms. The requests were denied because the club “cannot sponsor any political party”, for it had been “established for social purposes only”.[6]

Figure 1. Letter to A.M. Cassie. Source: Dalmatian Genealogical and Historic Society Museum and Archives, Box 4-5-b, File A-61.

Similarly, in October 1946, the club President J. Marinovich wrote to the President of the Labour Party in response to a request for support. Given Yugoslavia’s communist regime at the time, it is possible that the Labour Party thought the Yugoslav Club might provide a strong support base. But this request too was denied. Political ‘neutrality’ was expressly stated. “As you know” was added in pencil, perhaps suggestive of continual efforts to build a reputation as apolitical, before the unequivocal statement “we are not a club concerned in political activities so cannot support you openly”.[7] The last phrase of the letter, however, seems to suggest that the political disengagement of the club was based primarily upon a concern for the reputation of the Dalmatian community. “Individually”, Marinovich added, “we will do everything in our power to support you”.[8] The caveat draws distinction between member and club. Of course Dalmatians, like all people, had views about society that amounted to political beliefs. It was the club, viewing itself as an interface between members and Aucklanders, that wished to be perceived as neutral.[9] This tells us something of what it was to be an immigrant, from a politically-charged state like Yugoslavia, in a distant country like New Zealand in 1947. The focus on social activities that other Aucklanders themselves quite enjoyed was a safer choice for a community seeking acceptance.

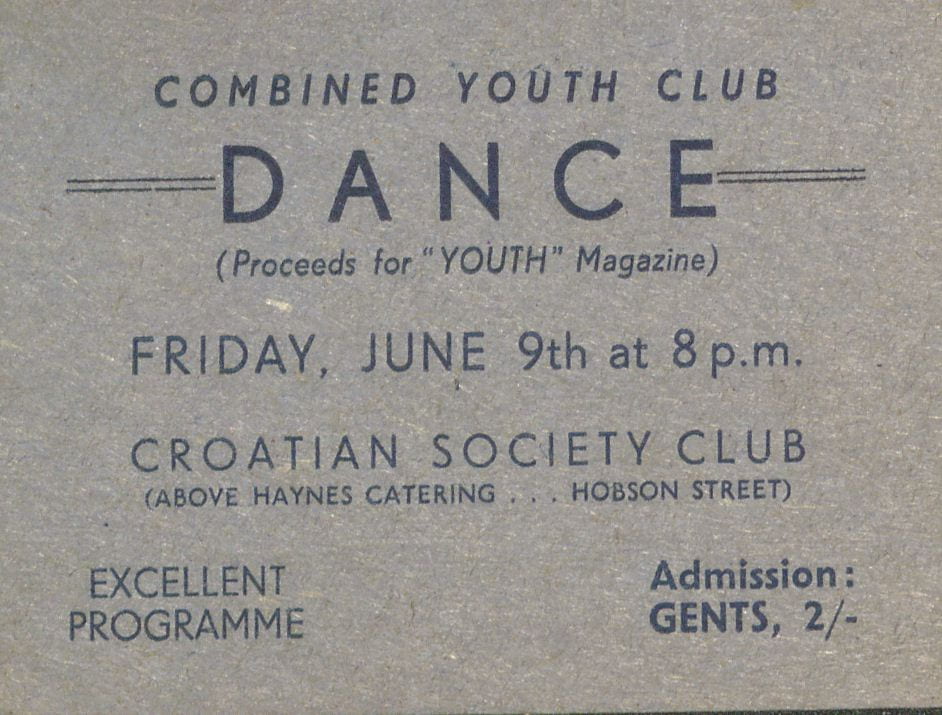

Figure 2. Combined Dance Ticket. Source: MSS A-139, File 11/1a, ‘Jugoslav Society invitations and papers’, Box 16, Series 11, Wilfred (Bill) McAra Papers, University of Auckland Special Collections.

The Yugoslav Benevolent Society took a very different approach to being Dalmatian in Auckland. It was overtly political. There is strong evidence in the documentation of the Society and the New Zealand Communist Party’s youth branch, the Auckland Young People’s Club, that the Benevolent Society had earned speculation that they were communist.

The Communist Party papers include a wide range of invitations and programmes to the Yugoslav ‘Marshall Tito Ball’. The name of the event suggests a higher level of comfort with open political views, but the fact that the Young People’s Club was so involved also indicates a strong link between the groups.[10] More tellingly, the two organisations held a combined dance at the Benevolent Society clubrooms in 1950.[11] The contrast with the Yugoslav Club is clear: as the latter rejected all requests to host political gatherings, the Benevolent Society held dances with the Communist Party in their rooms.

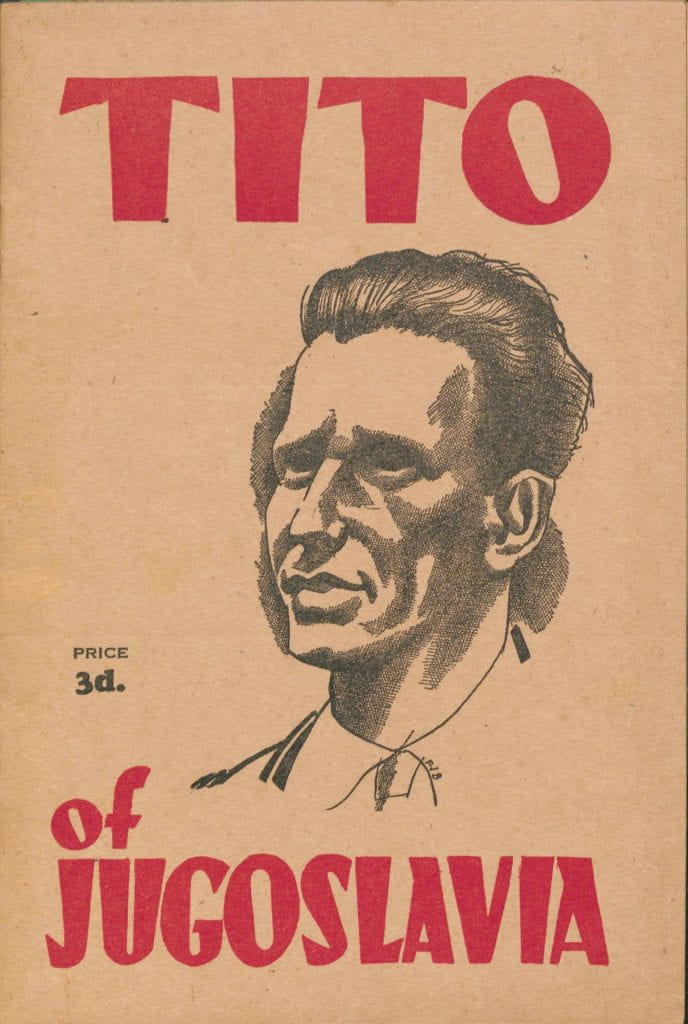

We should be careful not to draw too much implication from mere association with the Communist Party, but the political positioning of the Benevolent Society was not limited to organisational collaboration. In the Society papers, there is evidence that it distributed communist propaganda. The booklet below is a propaganda document about Marshall Tito, printed in Perth. Its presence in the Benevolent Society document, along with adverts for screenings of Soviet films, suggests the society had at least some role in distributing the material.[12] This seems a plausible claim, given Canvin has argued that this club was politically “radical” and distributed propaganda.[13] Moreover, in 1947 the Northern Advocate reported a comment from an anonymous Dalmatian claiming that the Benevolent Society was “intervening in New Zealand politics by distributing material and encouraging Yugoslavs to vote for Communist candidates”.[14]

Figure 3: Tito of Jugoslavia Booklet. Source: MSS A_139, File 11/10, Box 16, Series 11, ‘Jugoslav Association invitations and programmes, Wilfred (Bill) McAra Papers 1913-72, University of Auckland Special Collections.

The framing of the comments illuminates how these political tensions went to the core of what it meant to be a Dalmatian immigrant in Auckland. The interviewee perceived the Benevolent Society’s political nature as problematic principally because it brought “homeland politics” to Auckland and saw that reality as obstructive to acceptance in Auckland. Quoted by the Northern Advocate as a “prominent Yugoslav”, the person said the following: “there is a clear line of demarcation between those who wish to adhere to the politics of their homeland and those who wish to be assimilated into New Zealand society”.[15] To be political in a Yugoslav way was an issue for those who most wanted to assimilate. Here, again, is the balancing act facing Dalmatians wishing to rebuild their home in Auckland: for those who prioritised their Auckland identity, having clubs that presented as political organisations was a risk. Of course, those people tended to be well-resourced and landed, and those class interests are relevant.[16] On the other hand, those who wished to preserve political ties to home, or indeed those working-class Dalmatians who thought being left-wing was actually part of being Dalmatian, had no issue with their club taking a political position.

These questions of identity are complex. As mentioned, the intersection of class and ethnicity merits consideration. So too does the wave of migration the immigrants on either side of this debate arrived within. Those who left after Yugoslavia’s formation and the beginning of Tito’s regime were far more likely to be politically-wedded to the homeland.[17] Those who had come during the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s reign were more conservative.[18] Conservatism’s framing as ‘apolitical’ is also important to note: the Yugoslav Club undoubtedly perceived itself, and wanted to be perceived by Aucklanders, as politically neutral. But people in the Benevolent Society, recognizing the shared class interests of their neighbours, saw that choice as simply political conservatism.[19] This raises the question: is the act of forming an immigrant community club in some way inherently political? To what extent can a cultural club preserve ties to the homeland without simultaneously tethering itself to the politics of home?

The implications for Auckland of these Yugoslav debates, which began to resolve themselves as tensions lessened during the 1960s, are less difficult to assess. This city’s newspapers reported on the schism between two Yugoslav cultural societies, and in so doing had no choice but to explain to other Aucklanders the nature of those debates, and the views of the community. The clubs, intentionally or not, brought the politics of their homeland to Hobson Street, and to the minds of Aucklanders. Dalmatians did so because they were attempting to reconcile their identities. That stress is ever-present in this story. Nevertheless, the result was a period of time in which Aucklanders read about, and in some way considered, what it meant to be a Dalmatian Aucklander, and that meant necessarily trying to understand the Dalmatian community who had chosen their city as home.

[1]Northern Advocate, ‘Auckland Yugoslavs Split into Factions’, 15 October 1947, Page 4, Papers Past.

[2]Trlin, Andrew. Now Respected, Once Despised: Yugoslavs in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1979.

[3]Jelicich, Stephen. ‘The Yugoslav Community’, lecture, 1990, University of Auckland Special Collections, New Zealand Glass Case, Cassette LC90-42.

[4]Northern Advocate, ‘Auckland Yugoslavs Split into Factions’, 15 October 1947, Page 4, Papers Past.

[5]Barbarich, Tony. Oral history interview by Smita Biswas, 30 July 2015, Record OH-1210-020, Dalmatian Genealogical Society Collection, Auckland Central Library Special Collections.

[6]Letter to A.M. Cassie, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Box 4/5-b, File A-61, ‘Club Correspondence 1943-47’.

[7]Letter to Labour Party, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Box 4/5-b, File A-61, ‘Club Correspondence 1943-47’.

[8]Letter to Labour Party, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Box 4/5-b, File A-61, ‘Club Correspondence 1943-47’.

[9]Andrew Trlin, ‘Yugoslav Clubs’; Stephen Jelicich Winter lecture.

[10]‘Jugoslav Association (Also Yugoslav Society and All Slav Union) invitations and programmes. (Oliver B.Y. Gregory Material). File Item 11/10, Box 16, Series 11, MSS A-139, Wilfred (Bill) McAra Papers 1913-72 Collection, University of Auckland Special Collections.

[11]‘Jugoslav Association (Also Yugoslav Society and All Slav Union) invitations and programmes. (Oliver B.Y. Gregory Material). File Item 11/1, Box 16, Series 11, MSS A-139, Wilfred (Bill) McAra Papers 1913-72 Collection, University of Auckland Special Collections.

[12]‘Tito of Jugoslavia‘, Jugoslav Association (Also Yugoslav Society and All Slav Union) invitations and programmes. (Oliver B.Y. Gregory Material). File Item 11/10, Box 16, Series 11, MSS A-139, Wilfred (Bill) McAra Papers 1913-72 Collection, University of Auckland Special Collections.

[13]J.A. Canvin, ‘Yugoslavs in Auckland’, Masters Thesis in Anthropology, University of Auckland 1970, p. 56.

[14]Northern Advocate, ‘Auckland Yugoslavs Split into Factions’, 15 October 1947, p. 4, Papers Past.

[15]New Zealand Herald, Volume 82, Issue 25222, 7 June 1945, p. 6, Papers Past, https://:paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19450607.2.6.3.

[16]Barbarich, Tony. Oral history interview by Smita Biswas, 30 July 2015, Record OH-1210-020, Dalmatian Genealogical Society Collection, Auckland Central Library Special Collections.

[17]Trlin, Andrew. Now Respected, Once Despised: Yugoslavs in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1979.

[18]Trlin, Andrew. Now Respected, Once Despised: Yugoslavs in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1979.

[19]Barbarich, Tony. Oral history interview by Smita Biswas, 30 July 2015, Record OH-1210-020, Dalmatian Genealogical Society Collection, Auckland Central Library Special Collections.