By Elizabeth Larkworthy*

In September 1893, New Zealand women had won a huge victory – they had gained the right to vote. But what would they do with this newfound political power? And how could they use it to champion the greater good? These were the questions on the minds of small groups of politically inclined women that emerged in early twentieth-century Auckland.

Emily Patricia Gibson was one such woman – a political activist, feminist, suffragette and journalist active in Auckland during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though acknowledged by the National Council of Women upon her death in 1947 as “one of the few remaining political women pioneers of New Zealand,” she remains one of the lesser-known female figures in Auckland’s history.

Mrs Emily Gibson. Ref: Megan Hutching. “Gibson, Emily Patricia,” Te Ara Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3g7/gibson-emily-patricia. Courtesy of NZME/NZ Herald Archives.

Emily was the daughter of Edmund Ray, a barrister, and Anna Thompson. Born in Dublin in 1863, Emily spent her early working career as a compositor and proof-reader in the production of Catholic missals. She later moved to London, where she stayed for twelve years working for a liberal newspaper until it ceased operating.

In 1891 (now in her late twenties), Gibson immigrated to Aotearoa New Zealand, alongside her sister, the widowed Clementina Kirkby and her two children. Emily spent the rest of her life in Auckland, shaping local politics and putting down personal roots. After her arrival, Emily worked as a proof-reader for the Auckland Star. She married William Gibson in 1894, an Auckland asylum attendant and bricklayer, with whom she had three children. A working man, William was of like mind with Emily, becoming the secretary of the Auckland Bricklayer’s Union. At Rose Road, Ponsonby, their home was the venue for several Auckland Women’s Franchise League meetings and, later in the 1900s, the Auckland Women’s Political League.

Gibson’s contributions to women’s activism in Auckland spanned most of her adult life. Discovering that the movement for women’s suffrage was in “full swing” upon her arrival to Auckland, she and Kirkby enthusiastically joined the Auckland Women’s Franchise League (later renamed the Auckland Women’s Political League), presided over by prominent Auckland suffragist Amey Daldy. Subsequently, Gibson became one of the first Auckland women to record her vote after New Zealand women gained suffrage in 1893.

Emily soon became a pillar in the movement for women’s rights in Auckland. She acted as secretary of the Auckland Women’s Political League (AWPL) from 1907-1913 and 1914-1917, and was a founding member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) Auckland established in 1916. Gibson was also closely aligned with the New Zealand labour movement, joining the Labour Party soon after its founding in July 1916.When the WILPF became the Auckland Women’s Branch of the Labour Party in 1925, Gibson acted as the corresponding secretary until the two organisations split in 1930. Activism appears to have run in the family with her first child, Elizabeth Ray Gibson (Ray Wynn), eventually becoming president of the Auckland branch of WILPF and of the Auckland Women’s Branch of the Labour Party in the 1960s. Wynn also contributed her services as secretary to the Branch for fifteen years.

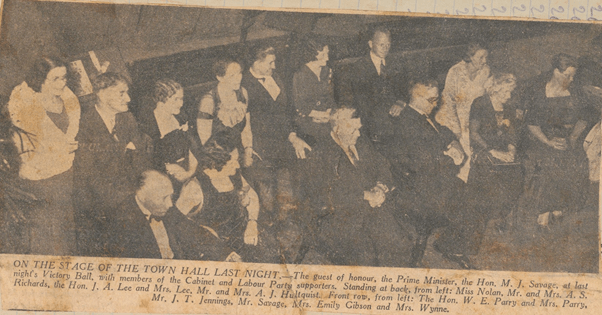

Emily and her daughter, Ray Wynn, seated next to Prime Minister Michael J. Savage at the Labour Party Victory Ball in 1935. Emily is in the front row, second in from the right. Emily Gibson scrapbook. 1936-1947. MSS & Archives 2014/9. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning.

Though Emily stopped working for the Auckland Star when Ray Wynn was born, journalism remained a key tool in her campaign for political reform. Throughout her life, she submitted articles and poems of political protest to Auckland papers such as the Auckland Star and New Zealand Herald, as well as the labour journal the Māoriland Worker and communist newspaper The People’s Voice. She also served on the advisory board for the left-wing women’s magazine Woman To-day, contributing several articles over its short run between 1937 and 1939. Thus, with weapons of “voice and pen,” Emily battled against the injustices she saw in her society.

Emily was a socialist, but she realised that, in the fight for change, “we [political women] were not living under socialism, we had to deal with conditions as we found them.” Seeking change from both local and national authorities, she fought steadfastly for various causes – from the rights of women, workers, and children to the need for world peace.

“Nothing is ever settled until it is settled right” – Emily and the Auckland Women’s Political League.

The work of Auckland women did not end once they had gained the vote. This much is clear in Gibson’s 1907 poem, “The Woman’s Place,” pasted inside her scrapbook and published in the Auckland Star. Written in response to the idea that “a woman’s work lies at home,” Emily writes:

“While a wrong remains unrighted

While children go unfed

While willing hands are idle

And strong men beg for bread;

While Might is Right and Giant Creed

Enslave the human race,

In the vanguard by her brother—

That is the woman’s place.”

In Gibson’s view, women, now empowered by the vote, could no longer afford to stand idly by while injustice remained rife. During her time as the Auckland Women’s Political League’s (AWPL) secretary, Emily repeatedly expressed frustration with the seemingly widespread political ‘apathy’ of women.As she remarked in one Māoriland Worker article, “there is only a small portion of any community who will take an interest in public affairs, more especially is this the case where women are concerned.”

This was apparent during Emily’s years as secretary for the AWPL, whose membership hit a maximum of 35 during the 1900s. With Amey Daldy, the previous president of the League, entering old age and unable to run meetings, the AWPL went into recess in 1905. In 1907, the League was revived, with Gibson as secretary and Kirkby as president.

Perhaps the best reflection of the aims of the revived League are summarised in a draft of the objectives of the League attached to the 1912-1916 minute book. Their aims included removing the ‘disabilities’ of New Zealand women, such as being unable to become members of parliament, and unequal pay. The League also aimed to provide opportunities for women to discuss matters of “public importance.” As part of the League, Emily took part in efforts to remove the parliamentary disability for women, to raise the age of sexual consent (which was 16) to the same age a girl could consent to her marriage (21), and to improve the working conditions of factory women in Auckland.

In Auckland, Gibson directed her efforts towards addressing the disparities in treatment between male and female school-teachers. One resolution proposed by Gibson in a 1908 AWPL meeting urged the Minister of Education, George Fowlds, to apply the principle of “equal pay for equal work” to female teachers, given that “in present conditions no female teacher is allowed to hold the position of headmistress in any large primary school.” The example of Emma Rooney, who had opened the Richmond Road primary school in 1884, stood out in Emily’s mind. According to Emily, Rooney had been ousted from her headmistress position and transferred to a ‘back-country’ school on the Auckland Board of Education’s insistence. This was because, Emily stated, the Board had realised that it “would never do” to have a female headteacher when there were men available for the job. The Board removed Rooney as headmistress, despite much protest from pupils and a delegation of women from the Auckland Women’s Liberal League in 1895, including Emily.

Gibson’s insistence on the issue arose again in 1910 when she wrote to the Auckland Star on behalf of the AWPL, urging the Grammar School board to allow female teachers to apply for the headmistress role at the girls’ Grammar School. For Gibson, the lack of female headteachers was symptomatic of a broader issue in Auckland society. Only a small minority of women participated on public boards, committees, municipal councils, and other public positions, even after women had gained the vote. As Emily remarked in a New Zealand Herald article in 1912, the number of Auckland women at that time on public boards and school committees could be “counted on one hand.” Nineteen years after gaining suffrage, only two women had represented Auckland on municipal councils, in Parnell and Onehunga.

Past Auckland Women’s Franchise League members and their daughters gather in September 1940 to mark the 47th anniversary of women’s suffrage – Emily sits in the front row, far right. Emily Gibson scrapbook. 1936-1947. MSS & Archives 2014/9. Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning.

In her articles, Emily urged Auckland women to come forward and grasp the newfound political power on offer after receiving the vote. Gibson often blamed New Zealand women for not having done more with the vote, with little consideration of other social conditions that might have prevented them from coming forward. It was, in her view, “owing entirely to women’s own apathy” that at this time, almost all prominent public positions in New Zealand were held by men. As part of efforts to see this rectified, the AWPL nominated its members Mrs Kirkby and Mrs Rule as candidates for the Auckland school committee elections in 1910. Gibson also nominated female candidates to sit on the Auckland hospital charitable aid board in 1915. In addition, the League actively supported female trailblazers such as Dr. Florence Keller and Ellen Melville in their bids for local elections.

Gibson also spent her time as part of the AWPL fighting for “purely local issues” that would improve the lives of Aucklanders. In response to the shortage of female toilets in Auckland, Gibson and the AWPL “badgered” the City Council into building the ladies convenience at Grafton Bridge. Another Auckland focus of Emily’s was the rising costs of living in the city. In her attempts to reduce living costs for Aucklanders, Gibson agitated the government to establish a state coal mine in Auckland, due to the high price of coal that continued to rise leading up to the first world war. From 1908 to 1913, Gibson also repeatedly implored the City Council to establish a municipal fish market in an attempt to address Auckland’s scarcity of fish and “exorbitant” prices.

Gibson utilised her role in the AWPL to overturn injustices in the city. Particularly, she sought more political power for women and to improve the living conditions of her fellow Aucklanders. However, the underlying theme in all this work was her wish that “the great mass of women had understood the power the vote put into their hands and used it accordingly.” If this had occurred, Emily said, “we could have revolutionised matters and made New Zealand what it is sometimes erroneously called – a paradise.”

Women for peace and freedom

As part of the WILPF in Auckland, Emily’s work took a more international focus. After leaving the Auckland Women’s Branch of the Labour party in 1930, Gibson acted as the corresponding secretary for the WILPF. Her work included maintaining contact with peace movements locally and internationally, including Britain, Australia, and the WILPF’s international body in Geneva. Emily joined a small group of women fighting for peace and justice on a national and international level. Throughout the 1930s, monthly meeting attendances were often small, numbering between 10 and 20 members. Despite financial difficulties and small membership forcing the League to form a ‘corresponding group’ separate from the international body of WILPF in 1932, Gibson’s presence remained constant.When the League again became a section of the WILPF in 1933, its members credited Emily with holding them together during their period of difficulty.

Gibson’s duty to vulnerable women and children carried over to her work in this League. During the Depression, she raised her voice in the League’s demands for relief for unemployed women and girls.The League worked closely with the Auckland Unemployed Women’s Association in attempts to bring the issue to the governments’ attention. In addition, as part of the League’s years-long protest against the Child Welfare Act of 1925, Gibson used her journalistic talents to point out the abuses of power occurring under the Act and injustices inflicted upon Auckland children in a 1937 issue of Woman To-day.

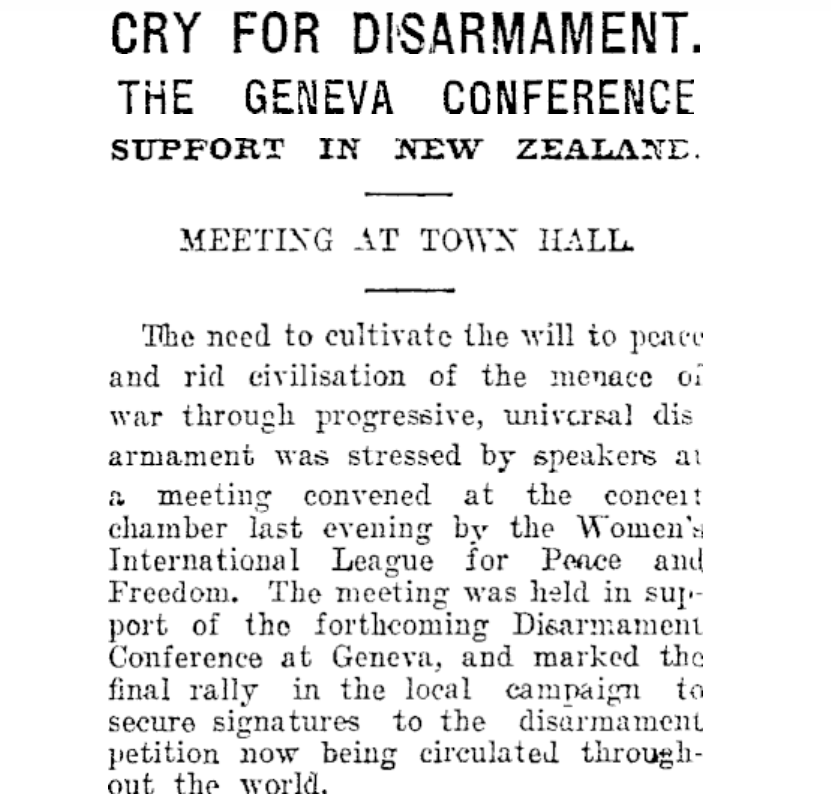

One of Emily’s largest efforts as part of the WILPF was her role in gathering signatures for an international petition for world disarmament, sent out by the WILPF headquarters in Geneva. Gibson received requests for petition forms from “all over New Zealand” and led the effort to organise Auckland WILPF members to collect signatures between 1930 and 1931. The League also placed Emily in charge of organising a disarmament meeting in the Auckland Town Hall. This was the “final rally” in the League’s bid to attain more signatures in Auckland. The meeting provided a forum for local leaders, including speakers on behalf of the League of Nations Union, the Auckland University College, and Auckland-based Labour politicians such as George Fowlds and John A. Lee, to express their support for “progressive, universal disarmament.” Gibson, alongside Miriam Soljak, spoke on the efforts of their League towards peace since the inception of the WILPF in Auckland. The efforts of Emily and the WILPF were rewarded in 1932, with signatures collected nationally totalling 41,928.

A clipping from the Auckland Star describing the proceedings of the Auckland disarmament meeting. “Cry for Disarmament,” Auckland Star, September 29, 1931, p.5.

With the beginning of the Second World War, the League declined. In 1940 Emily expressed her hope for the League’s revival when peace arrived, but four years later she reported that membership had dwindled to “almost nothing.” Eventually, the League stopped functioning in 1946, one year before Emily’s death.

Throughout her life, Emily’s dedication and persistence shone through in her activism. At a time when only a minority of Auckland women spoke out, she consistently fought for the rights of others more vulnerable than herself. If nothing else, she could bring attention to the injustices experienced by others through her writings in local papers. She pushed for increased political power for women, from the vote, to women on local councils, to female MPs. She was a passionate fighter in the cause for peace, believing war an unnecessary evil that caused widespread violence and misery. Instead of seeking upheaval, she carried out her duty to rectify injustices by working within the AWPL and WILPF to seek reform from the local, national and international powers of the day. Though she was not always successful, she made her mark in Auckland history as a political pioneer. As Emily wrote in 1914, “I have heard women say the vote is no use. They are wrong. It is not everything, nevertheless it is a necessary weapon.”