By Ione Cussen*

The Salvation Army Bethany Home in Auckland was a much-loved and well-utilised private maternity hospital and home for single mothers. Running from 1897 until 2011, Auckland Bethany was one of seven Bethany Homes that operated throughout the country. These homes witnessed over a century’s worth of developments in women’s rights, sexual health, birth, and parenthood. Established as a refuge for single mothers who needed assistance, Bethany grew to be known as a home that would offer help to women in need, without the weight of religious expectations or moral punishment that was often associated with homes for single mothers.

The 1960s and 1970s present as a significant period in the history of the Bethany Home, as it allows the exploration of transforming attitudes towards single mothers at a time of great change in Auckland. Although change was in the air, general attitudes towards sex, contraception and abortion remained largely conservative, especially in regard to single women. The stigma of sex outside of marriage was still considerable. The contraceptive pill became available to New Zealand’s married women in 1961. Although, the pill was not distributed to single women until 1973, due to concerns that freely available contraception would facilitate extra-marital relationships.

The 1961 Crimes Act amended the existing legislation surrounding abortions, although it did little to provide women with reproductive autonomy, deeming that an abortion was only legal if it was performed “in good faith for the preservation of the life of the mother.” A media focus on backstreet abortions in the early 1970s brought the issue of safety and accessibility into the spotlight. The ongoing and highly charged debate eventually led to the opening of Auckland’s first abortion clinic in 1974, and the 1977 Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion Act, which although still restrictive, did make accessing a safe abortion easier. Prior to these drastic developments in women’s reproductive autonomy, extra-marital pregnancy was often met with stigma and struggle. With few options available, many women sought help from organisations like the Bethany Home, to support them during pregnancy and birth, and make plans for the future.

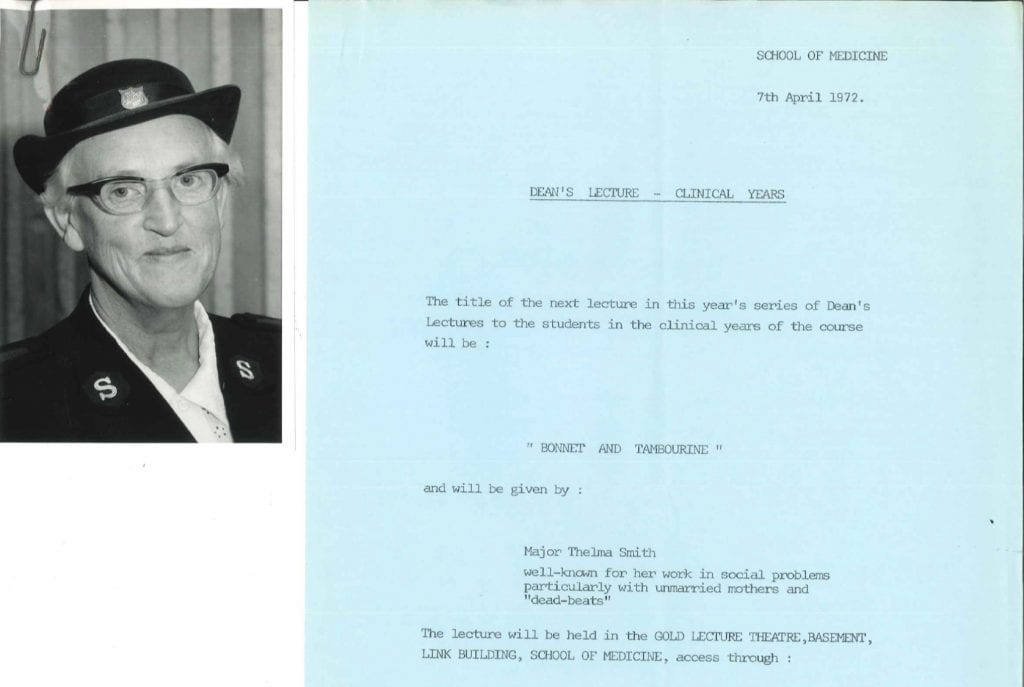

The Auckland Bethany Home has a remarkably positive history considering the often negative and moralistic connotations that are associated with homes that cared for single mothers. Captain Thelma Smith (matron from 1950-1970) and Major Eunice Eichler (matron from 1970-1992) saw Bethany through great periods of social change. They both contributed significantly to developments in maternity care and adoption procedures, including advocating for state assistance for single mothers, the development and implementation of “open adoption” and the inclusion of fathers during labour and birth. Countless sources referred to the political vigour and personal compassion of both Captain Smith and Major Eichler. Over their combined forty-two years of service at Bethany, they emerged as ceaseless and passionate advocates for the rights and welfare of mothers: be they single, or otherwise. Major Eichler explained that Bethany provided single, pregnant women with “a neutral place [and] unpressured time to sort themselves out, to consider [their] options and to make an informed decision.”

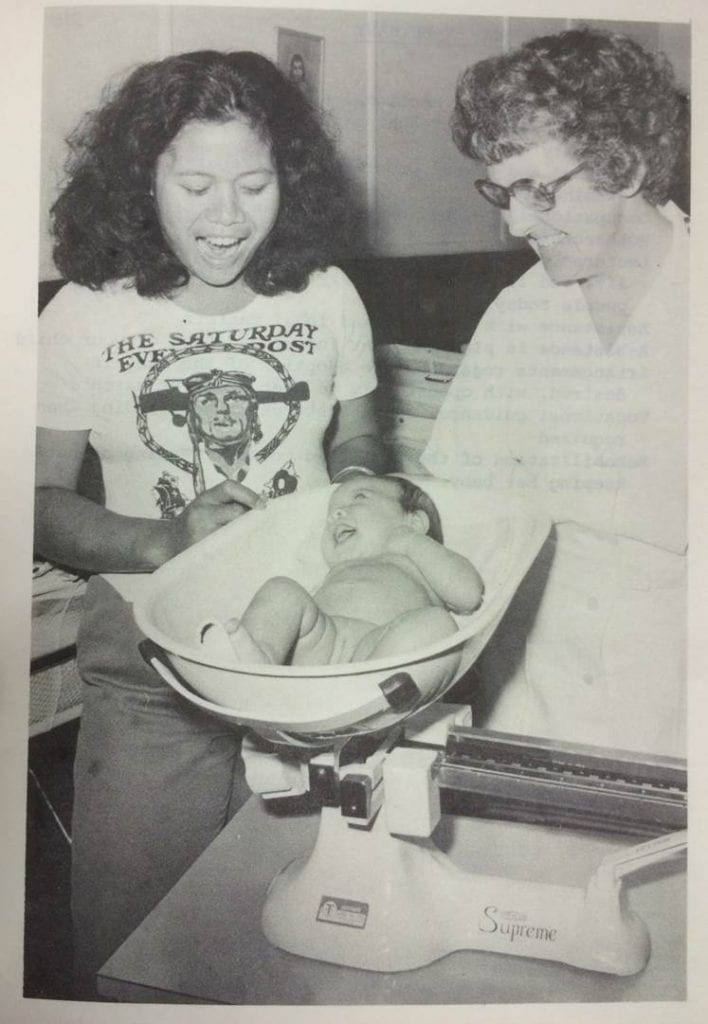

At Bethany, a heavy emphasis was placed on providing well-rounded care. In addition to physical check-ups, the mothers were given antenatal and relaxation exercises, and group talks about what to expect during labour. Counselling for both the mother and her family was on offer, and social events and outings were considered to be of upmost importance. Educational talks and workshops took place, with discussions ranging from relationships, and contraception, to vocational guidance, and how to care for a child. The care offered at Bethany was innovative for the era. Most homes that cared for single mothers during the 1960s and 1970s focused on the physical elements and moral repercussions of pregnancy and childbirth, rather than the holistic needs of individual women. The personal affection and appreciation that many women at Bethany had for the staff and Matrons was evident in letters sent back to Bethany after residents had returned home. Letters exclaiming “thanks for everything”, “with all my love”, and “I don’t know what I would have done without you”, clearly paint a picture of a place that had a positive impact on the lives of many.

Bethany’s reputation stood in stark contrast to other mother and baby homes in Auckland. For example, the Anglican St Mary’s Home in Otahuhu, established in 1884, has had scores of retrospective abuse accusations from women who felt that they were ill-treated, and petitions for an official inquiry into “forced adoption” has been lodged with Parliament as of 2016. Numerous women in the care of St Mary’s during the 1950s to the 1970s have attested to being sexually abused by doctors; made to perform hard labour whilst heavily pregnant; having their babies forcibly adopted without their permission; and being slapped and refused pain relief whilst giving birth. Historian Joanne Richdale has argued that the Anglican-run women’s homes in Auckland were considerably concerned with moral reform, and had a hardening of attitude, particularly as they moved into the twentieth century. The lack of compassion exhibited by the St Mary’s Home, up until and during the 1970s, was justified by the Home as a means to reform the “fallen” ways and correct the moral compasses of women who had extra-marital sex, be that consensual or not.

The Maternity Hospital at Bethany catered for both married and unmarried mothers. By the 1970s, the increased popularity of hospital births, and tight limits on available beds, meant that many smaller maternity homes saw an enormous increase in patients. Married women flocked to Bethany for the birth of their babies, encouraged by its reputation of being “more friendly and less impersonal than the larger maternity hospitals,” such as St Helen’s Hospital or National Women’s Hospital. Bethany allowed fathers to be present during the birth of their child, a progressive move that was largely forbidden in other hospitals. Mary Dobbie of the Parents Centre explains that Bethany’s popularity was due to the “warm, family centred approach to obstetrics, its emphasis on full father participation, [and] its willingness to meet the needs of the young and the unorthodox.” Bethany was “a haven for those who found the impersonalised care of large institutions upsetting and who feared the routine application of drugs and technological procedures.” Letters of thanks from Bethany’s private patients provided similar justifications for the home’s popularity. One such letter, from a woman who gave birth in 1976, described her experience as “exceeding anything that we could ever have hoped for,” she went on to write that “the personal interest taken by Matron and all her staff in each and every mother and baby is a great credit to both the hospital and the Salvation Army.” The healthy influx of private patients not only took some of the pressure off already stretched maternity services in Auckland, but it also helped to finance the charitable work of caring for unwed mothers.

The Salvation Army Bethany Home in Auckland cared for single, pregnant women in need of support. Although their day-to-day care played a significant role in helping individual women, the work of Bethany Matrons Captain Thelma Smith and Major Eunice Eichler also had a major impact in shaping new sex education methods, and changing adoption laws.

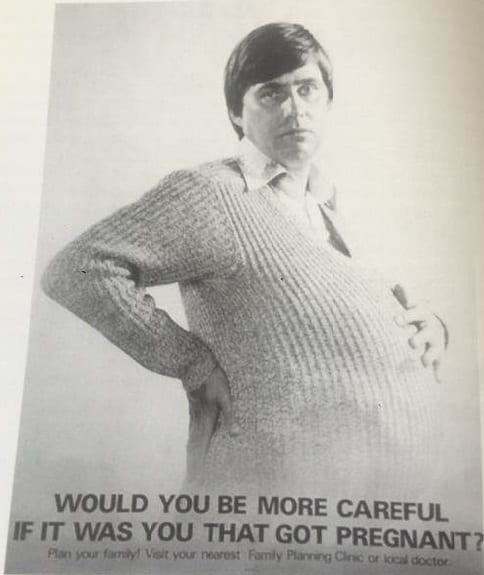

The Matrons at Bethany saw sex education as a significant part of equipping women with knowledge of their own body, so that they could make informed decisions; an approach which was a far more holistic and empowering than the status quo. During the 1960s and 1970s, sex educators typically kept a staunch focus on chastity as an ideal, despite the growingly sexual nature of popular culture. As historian Helen Smyth has pointed out, “sound sexual knowledge could not be said to have kept pace with the more open and explicit sexual culture.”

The Matrons at Bethany, aware of this lack of education, developed a new means to share with teenagers the reality of what was involved with teenaged motherhood. Volunteer residents at Bethany, often heavily pregnant, visited senior high school classes to “preach [the] petting pitfalls.” The teenagers gave lectures about how they fell pregnant and what difficult choices lay ahead of them, with the hope that “it may prevent some other girl becoming pregnant”. Major Eichler explained that the whole process is “done very carefully… the girl must really want to go along and give a lecture, there is no force or even suggestion, they have to raise the subject.”

The introduction of these lectures came alongside tape recordings of “startling confessions” from pregnant fourteen and fifteen-year-olds, who explained “exactly how they got into trouble.” These tapes were designed to debunk many inaccuracies about safe sex, with the most troubling example coming from a pregnant 13-year-old who believed that “it was impossible to become pregnant if both partners held their breath.” The tapes became a popular form of education within high schools, but Major Eichler asserted that the presence of a pregnant peer more powerfully enforced the message, stating that “there is nothing that brings it home better than the real thing.”

Along with influencing sex education in Auckland, Bethany also contributed to major advances in adoption laws, encouraging adoption protocols that considered the welfare of the birth parents, as well as the children. Most notably, Major Eichler was amongst the first to implement open adoption in the 1970s. Open adoption gave the adoptive and birth parents an opportunity to meet before the adoption took place. The staff at Bethany found that this pioneering initiative eased the concerns of birth parents, giving the birth parents confidence that their child was going to a family where they would be loved, supported and wanted. Closed stranger adoption, on the other hand, restricted the information available to both parties. Whilst this did protect the identities of all involved, it often also led to greater anxiety and guilt on behalf of the birth parents, and a lack of knowledge about the child’s genetics for the adoptive parents.

The concealment of information also made it difficult for adopted children (if they so wished) to reunite with their birth parents as an adult. Importantly, open adoption demystified the adoption process. It removed the secrecy and, as Barbara Sampson has observed, put a human face on this often highly emotional process. Instead of having no knowledge about who was adopting their child, birth parents could select the adoptive parents that they liked, based on files that contained their background, photographs, beliefs and details. From 1973, Bethany encouraged women in their care to opt for open adoption; finding that when the actual hand over took place, it was done in an atmosphere of trust and openness.

Like many homes for single mothers, Bethany’s demographic began to change dramatically towards the later part of the twentieth century. Stigma towards single parents began to ease, and greater support existed for those to choose to pursue parenthood. This was in part due to political changes. The Social Security Amendment Act of 1973 introduced the Domestic Purposes Benefit, which provided single parents with financial support and subsequently, means and opportunity to keep their child if they wished. Adoption was no longer the only option. Increased access to contraception and abortions also gave women more control over their sex lives and bodies. With such great social changes afoot, Bethany turned its focus to the younger demographic of pregnant girls and women, who now made up the majority of their residents, and did until its closure in 2011. Education and support remained cornerstones of Bethany’s work, leaving a legacy of kindness in a history that was so often filled with fear and shame.

Primary Sources

Wellington Booth College of Mission: Salvation Army Archives, Auckland Bethany Centre Records, 1913-1990.

Newstalk ZB, 2018.

New Zealand Herald, 2005.

The War Cry, 1973.

Secondary Sources

Dobbie, Mary, The Trouble with Women, Queen Charlotte Sound, 1990.

Else, Anne, A Question of Adoption: Closed Stranger Adoption in New Zealand 1944-74, Wellington, 1991.

Richdale, Joanne, ‘The Women’s Home, 1884-1904: Reclaiming Fallen Women in Nineteenth Century Auckland’, MTheol Thesis, University of Auckland, 2004.

Salvation Army (Auckland Congress Hall Corps), Heart of the City: Auckland Congress Hall Stories 1883-2008, Auckland, 2008.

Sampson, Barbara, Women of Spirit: Life-stories of New Zealand Salvation Army Women from the last 100 years, Wellington, 1993.

Smyth, Helen, Rocking the Cradle: Contraception, Sex and Politics in New Zealand, Wellington, 2000.