By Mark Sinclair*

There is something about broken glass that seems to resonate through every riot. Whether it is the shattering of a transparent fragile barrier that separates the poor from owning what they can clearly see but not afford or, the scornful reflection that in certain lights looks back at the potential stone thrower and motivates a violent act that destroys a despised image. Whatever the motivation, the smashing of shop front windows seems to be a universal release for the frustrated and the angry. The 1932 Queen St riot was the most violent act of the 1930s Depression in New Zealand. Yet the Riot Act was not read, the Police were not issued with firearms, and nobody was killed. The riot can now be seen as a foundational confrontation in which some saw the potential for European style social conflict – “a call from Goebbels” – and others saw a sign that, in both social and economic terms, New Zealand had the space and the national desire to be better than that.

Pickets and broken windows Queen St April 14th 1932. Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19320420-43-1

In the winter of 1931, there were 50,000 registered unemployed in New Zealand. Twelve months earlier there had been only 5000. By late 1932, in the depths of the depression, it is estimated that 100,000 were unemployed – 16-20% of the workforce. Many observers of the 1930s ‘slump’ saw it as a contest between “desperate people and callous and unfeeling authorities be they bankers, businessmen, officials or most often, politicians in government”. On April 14th and 15th 1932, this contest became violent when desperate relief workers and the unemployed aggressively challenged both the authorities and the property rights of the wealthy by rioting in Queen St and Karangahape Rd in Auckland.

“Backblock camps for the outcast, the superfluous,

reading back-date magazines, rolling cheap cigarettes,

not mated;

witnesses to the constriction of life essential

to the maintenance of the rate of profit

as distinct from the gross increment of wealth.”

A.R.D. Fairburn from Dominion (1938)

On the morning of April 16th, when this rioting was over, there were 200 people injured, 250 glass windows smashed and 85 arrests which resulted in 83 convictions. Of the 30 policemen directly engaged in the fighting outside the Auckland Town Hall, 21 were injured. The New Zealand Herald would report the events under headlines of “Mad Orgy”, “Uncontrolled Mob” and “Wanton Destruction” but the Auckland Star editorial showed greater empathy when it wrote “though the actual damage done is serious, it is not really as grave as the exhibition of savagery that produced it.” The poet and relief-worker A.R.D Fairburn, inspired by the riot, wrote “the thought of a plate-glassless Queen St gives me fresh hope for humanity… I didn’t think they had the guts.”

First-hand experience of the riot would also influence the work of Robin Hyde and, even more directly, John Mulgan. Both would see the riot as a very real consequence of the poverty and humiliation that was felt by the urban poor and treat it as an event in the Depression which focused their perception of what life in New Zealand should be like in the future. For Hyde the riot had a purpose that must not be forgotten. “The job will be keeping things alive… If change is to achieve anything the memory of ‘what people wanted in the first place’ must not be lost.” For Mulgan the riot created a more socially aware protagonist “If fellows like me make more trouble now than they used to, it’s because they’ve got more sense.”

John Mulgan https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/john-mulgan

Iris Wilkinson (Robin Hyde) was a reporter in the midst of the disturbance. She is responsible for two of the most memorable images of the riot, when recalling the sight of the student Special Police as an “intrepid force of novices”, and the “exclamation of an enormous and derisive lady in the throng, “Yah,” cried she, “Glaxo babies!” Hyde is fascinated by the smashed shop windows, commenting that Auckland’s two most prominent glazing companies, Phillips & Impey and Smith & Smith, made a fortune, but both actually “lost not a pane” from their own premises. The media and publicity were also an issue. Hyde commented “Since Massey died, we seem to have hit the newspaper world to the boundary only twice. Once by indulging in a most expensive earthquake, once having a riot before our plate glass was insured.” In 1939 Hyde would take her own life while living in poverty in London.

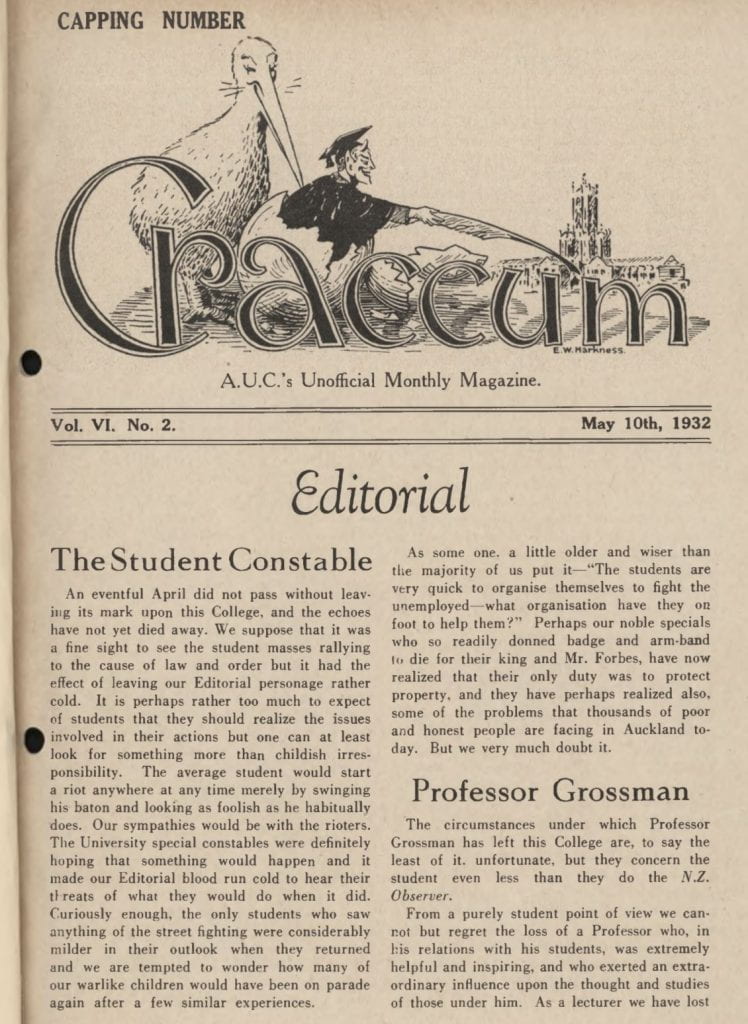

In 1932 John Mulgan was an exceptional student at the University of Auckland and an able and courageous editor of the student newspaper Craccum. His views supporting the unemployed after the riot were not well-received by conservative forces within the Student Association or the Professorial Board.

“Perhaps our noble Specials… have now realised that their only duty was to protect property, and they have perhaps realised also, some of the problems that thousands of poor and honest people are facing in Auckland today. But we very much doubt it.”

John Mulgan Craccum May 1932

Although he was regarded by many as the best candidate, Mulgan was denied the University’s nomination for a Rhodes Scholarship in 1932 and again in 1933. Notwithstanding this, he made his own arrangements to enrol at Oxford using private means. He left in 1933, and would never return to New Zealand.

Mulgan wrote two books. His first was the novel Man Alone, published in 1939 by Selwyn and Blount and, more influentially, re-published in 1949. His second book, Report on Experience, was a war-time memoir. Incomplete at his death in 1945, it was later finished by his wife and published by Oxford University Press in 1947.

Since 1949, Man Alone has been regarded as the first truly quintessential New Zealand novel. It was, for many years, studied extensively in New Zealand schools and universities. For this reason alone, it could be described as the most influential New Zealand novel of the twentieth century. Mulgan wrote Man Alone at Oxford in 1938, some six years after his personal experience of the riot and his editorial in Craccum. His vision and loyalties had become clearer by then. “There were thoughts within him that had not been there before.” The unemployed were no longer just deserving of pity. They were now fellow New Zealanders suffering physical pain, fear, economic deprivation and the humiliation that the inability to find work had forced upon them. “To them it was the releasing of accumulated desire, a payment for the long weeks and months of monotony and weariness and poverty and anxiety that would be satisfied like this in a few moments of freedom and destruction.”

The central character in Man Alone is Johnson, who joins the march of the unemployed up Queen St on April 14th. Johnson witnesses the fighting outside the Town Hall, the use of fence palings to attack the police and the surge back down Queen St when the “shop windows began to go” as the fast runners “broke everything they saw without caring”. After leaving the mob, Johnson stops, and leaning on the railings outside the Ferry Building, he turns and looks back. “It was quiet now, though even from where he stood, he could see light catching on broken glass strewn across the street and the shop windows that he saw were gaping and glassless. It was a clean business of wrecking that his friends had made.”

Mulgan’s description of Johnson’s experience is in accordance with the key elements of all reporting on the night of the riot including that of both the Auckland Star and the New Zealand Herald. Although Man Alone is a novel, Mulgan had probably read the dailies, and his story is true to the record of experience in terms of its perspective and description of the riot. The fence palings became the stuff of legend after Colin Scrimgeour, the Methodist City Missioner and the ‘owner’ of the fence that was destroyed, made a controversial radio broadcast the next day, when he proclaimed:

“If what happened last night makes authority act to help desperate people obtain the justice they deserve, the pickets torn off the fence of the Methodist Mission in Airedale Street will have caused this church to give to the people the most outstanding service of the church’s hundred years of history.”

Mulgan begins Report from Experience with a description of New Zealand, a nation that he had not seen since 1933. Reflecting on his experience of the riots in Queen St, he makes the observation that “We had lived as a community in a fair state of material happiness and unconcern and now the insubstantial nature of this living came home to us. It was emphasized by hungry men who threw rocks at shop windows and by an underlying hatred in the eyes of relief workers on the roads.”

His vision for New Zealand’s future is driven by his belief that New Zealand was a country where there was room to change, where the pioneer spirit of individualism was tempered by an appreciation that people turned out to help their neighbours when they were in difficulty and “survived because they lived as a community and not as men alone”. It was an accommodating nation where, after the war, there would be many more European immigrants, and “Girls would wear bright dresses, and men would talk quietly together. Few would be rich and none would be poor.” Written during a desperate period of the Second World War, when Allied victory over the Axis powers was by no means certain, these lines reflect a courageous optimism that New Zealand would be an egalitarian society offering a valuable social example to a better post-war world.

Mulgan’s life also ended tragically. On the evening of Anzac Day 1945, in Cairo, he took his own life by taking an overdose of morphine. He was 33. The deaths by suicide of both Hyde and Mulgan are beyond explanation. Both were young and optimistic for New Zealand’s future place in the world. Both must have hoped that the country would offer the chance for their children to live happy and fulfilling lives. Yet, while they could hold this vision for others through dark times, they would could not hold it for themselves and as a consequence both would never return to New Zealand and both would die alone.

“That’s Auckland mate – the Queen of the North.”

“The what?”

“The Queen of the North. That’s what they call it in Auckland. This is God’s own country.”

“It looks alright.”

“Its not a bad little town – nor a bad little country either. It looks small after London though, don’t it mate?”

John Mulgan – Man Alone (1939)