By Chris Turnbull*

Auckland is a Pacific city. Many of us are familiar with how Pacific Island settlers were drawn to Auckland by the demand for agricultural and then manufacturing labour in the 1960s and 1970s, but our relationship with the Pacific has an earlier history. This paper describes how the foundations of today’s Pacific city were laid in the 1840s, through the interaction of Pacific leaders, New Zealand’s Governor, and the missionary community. Three leaders, George Tupou, George Grey, and George Selwyn were influential in the formulation of a Pacific policy which had Auckland at its centre.

The first official contact between Auckland and the Pacific appears to have been initiated by Tonga’s Tu‘i Kānokupolu, Josiah Tupou. In February 1844, Tupou wrote a ‘Memorial’ to Queen Victoria, sending it through the Methodist Reverend Lawry to Governor Fitzroy in Auckland. According to Tupou, Tonga ‘had from of old been a separate and independent kingdom’, however, because of the ‘unfavourable conduct of the people of France’, ‘we now really fear that they have a design to take Tonga’, and he asked that Victoria ‘take us under Your Majesty’s protection’. This letter was sent to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Stanley, but there is no record of action or a response from either Britain or Fitzroy. After Josiah Tupou’s death in November 1845, attention was again directed to the Pacific by Reverend Lawry. In 1847, Lawry brought a letter from George Tupou, the new Tu‘i Kānokupolu, to Governor Grey enclosing a copy of Josiah’s earlier letter and noting that there had been no response. George Tupou wrote that ‘our minds continue as they were – we wish to be friends with England’, and ‘we do not wish to fall into the hands of any other nation’.

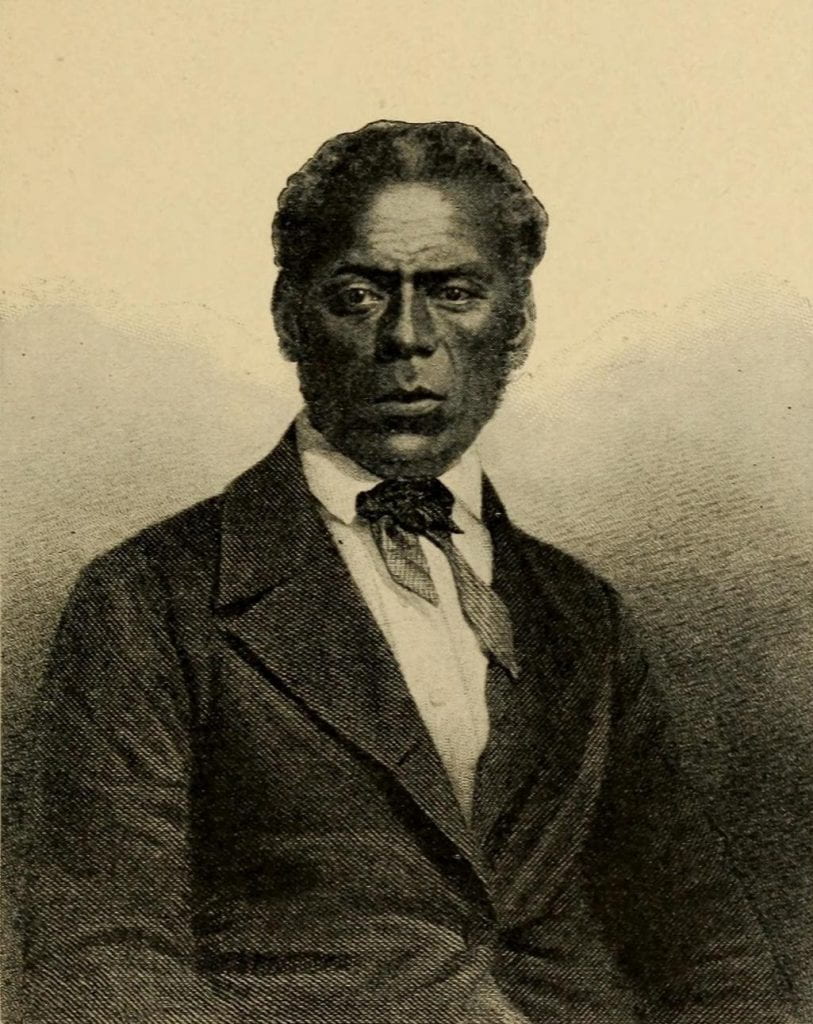

King of Tonga, George Tupou ~1860, J.F. Hurst, The History of Methodism, Eaton & Mains, New York, 1902, p. 125.

This time Grey responded immediately, assuring Tupou of his interest in Tonga and of Queen Victoria’s interest, in assisting in raising the inhabitants of Tonga ‘from vice and barbarism to Christianity and civilisation’. He sent his reply to Tupou with Captain Maxwell, Senior Officer of the Royal Navy, and asked Maxwell ‘to promote and confirm the feelings of friendship and regard which are at present entertained by these Islands for the British race’. Maxwell subsequently reported to Grey that in Tonga, ‘British protection is much desired by King George and many of the principal chiefs’. Maxwell invited Tupou to visit New Zealand and was positive that ‘such a visit and the intercourse and friendly relations that might be expected to follow, might result in vast benefits which would affect not only George Tubou and his Country but possibly also a large portion of the Polynesian Race’.

Grey then wrote to the Colonial Secretary, Earl Grey, noting that Tonga desired ‘to be brought under Great Britain, in the same manner that the New Zealand islands have been’. This goes considerably further than Josiah Tupou’s request for protection, or George Tupou’s expression of friendship, but Grey saw the communications with Tonga as presenting an opportunity, and he argued that any cost of establishing a civil administration would be compensated by an expansion in commerce. This assertion was not backed by any substantial analysis and Earl Grey was not persuaded. The islands were distant from New Zealand, would require a separate administrative and military presence, and there would be a significant initial cost to establish law and order. Britain was not interested in a new Empire in the Pacific, given ‘a deficient revenue and a disinterested population’.

While this first imperial initiative of Grey’s was unsuccessful, there was a more enduring consequence of Tupou’s expression of friendship. Bishop Selwyn had accompanied Captain Maxwell on his visit to Tonga, ‘at the request of the Governor of New Zealand, seconded by my own strong inclination’. This was Selwyn’s first visit to the Pacific from New Zealand and it appears to be when he finalised his plans for what became the Melanesian Mission. His original intention had been ‘to form a Polynesian College for the different branches of the Maori family scattered over the Pacific’. After his voyage with Maxwell, he appears to have been more impressed by the opportunities in the Western Pacific, noting that this was ‘the point upon which the Missionary energies of the New Zealand Church ought to be bestowed’. After returning to Auckland, Selwyn then made a return voyage to Melanesia to bring students back to the mission school at St Johns.

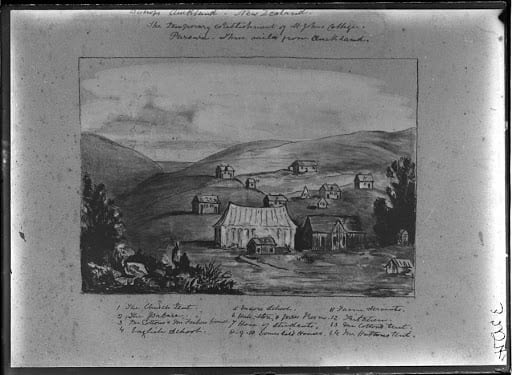

Sketch by Caroline Harriet Abraham of St Johns Theological College, 1852-55, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-3204.

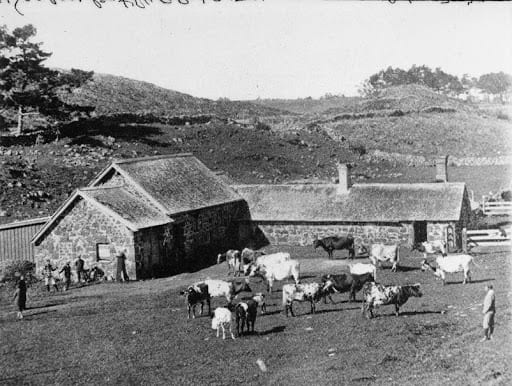

Selwyn’s Melanesian mission influenced Grey to support the establishment of further schools for Pacific Islanders. Grey believed that ‘promising children’ from the islands should be educated, ‘where they will be surrounded entirely by Christian associations, and where, also, they will be brought up in British customs and habits’. He encouraged the missions to establish schools in Auckland by offering grants of land, provided that they admitted ‘inhabitants of the islands in the Pacific Ocean’. Grey intended that the schools would be ‘a component part of that great system of missions which the piety and benevolence of Great Britain has established throughout the Pacific’. This would make Auckland ‘the metropolis for a considerable number of islands’ which would ‘certainly enjoy an extensive and lucrative commerce’. By 1853, the Anglican, Wesleyan and Roman Catholic churches had accepted Grey’s offer, establishing schools at St Stephen’s in Parnell, at Three Kings and at Takapuna.

Original stone buildings of Wesley College, Three Kings, 1904, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-2637.

Auckland’s early relationship with the Pacific was initiated by Josiah Tupou and George Tupou and their desire to establish political relations with the British empire. Grey’s response made an emotive case for the expansion of British empire in the Pacific, which, though well intentioned, lacked the political or economic analysis to persuade Britain. However, Grey retained his interest in the Pacific and developed a more carefully considered scheme to encourage the education of Pacific children in Auckland, so as to place Auckland within the Pacific and the Region within the British Empire. Early Auckland recognised and cultivated its place in the Pacific and its role as a Pacific neighbour and outpost of Empire.