*Lucy Mackintosh

Local, or place-based history, is often dismissed by academic historians as lacking an ‘analytical edge’, or as presenting places as fixed, stable entities that do not relate to national questions. But by relegating local narratives to a field outside of ‘real history’, historians can miss diverse, nuanced local perspectives on the past that are not visible in the archival sources that historians tend to rely upon. These narratives can give a very different perspectives on the past and can change the bigger picture.

My doctoral research explored places in Auckland where deep histories, both natural and human, have been woven together over hundreds of years, forming potent sites of history that have continued to affect communities in the city and across New Zealand. The study followed the remnants of these histories in three iconic landscapes in Auckland – Pukekawa/Auckland Domain, Maungakiekie/One Tree Hill and the Ōtuataua Stonefields. Using landscapes as an archive, it sought to uncover not only the stories that have been celebrated and remembered in Auckland, but also vestiges of stories that have been erased or forgotten. These stories tell us older, more complicated stories about iconic Auckland landmarks such as the obelisk at Maungakiekie and the Auckland Museum at Pukekawa, and highlight the importance of lesser known places such as the Ōtuataua Stonefields, where long and polarizing histories emerge occasionally as flashpoints.

Spanning the length of human occupation in Auckland, the thesis examined particular moments in each of the landscapes and explored how these histories have evolved and continue to shape the city today. Forgotten places such as the early Māori gardens of the Ōtuataua Stonefields, Te Wherowhero’s cottage in the Auckland Domain, the Ihumātao mission station, John Logan Campbell’s olive grove, Chinese market gardens in the Domain and sites of remembrance on Maungakiekie, allow us to understand histories that have not made it into our history books or memorials, but which still resonate through Auckland and beyond, whether or not most of us are aware of them.

The landscapes of Pukekawa, Maungakiekie and the Ōtuataua Stonefields show how Auckland’s volcanic soils, rivers and harbours are core historical factors that have actively influenced where and how people have lived across the isthmus. Their lava flows formed large areas of free-draining, fertile soils that have drawn people to them since humans first arrived in Tāmaki and provided key organisational devices for the shaping of the city.

These landscapes also remind us that histories prior to the arrival of European settlers in 1840 are not just a prelude, or pre-history, to the main historical events in Auckland. Rather, Māori histories, networks and knowledge underpin and explain the present in ways that are hard to recognise in less grounded histories.

Pukekawa, or ‘hill of bitter memories’ for example, commemorates those who died during the inter-tribal musket wars of the 1820s and 1830s. Pukekawa reminds us that the history of the Auckland cannot be adequately explained by the arrival of European settlers in 1840, but must be seen as part of ongoing tribal adjustments following the inter-tribal musket wars. Though this site is now marked by a Museum built as a memorial for those who died in the first and second world wars, the earlier, less visible wars evoked by the name of the hill are just as important for Aucklanders to remember.

At the Ōtuataua Stonefields, some of the deepest foundation stories of Auckland’s human history have been co-constituted with the physical environment and have shifted and evolved in ways that do not fit easily into European concepts of time and space. The continuities, fluidities and complexities of histories at Ihumātao also provide a counterpoint to histories that continue to emphasize the dominant narratives of particular ruptures in Auckland’s history, such as the Te Taoū invasion of Tāmaki and the establishment of the European town of Auckland in 1840. Though these moments had a significant impact on Auckland’s history, they were not experienced uniformly across the isthmus.

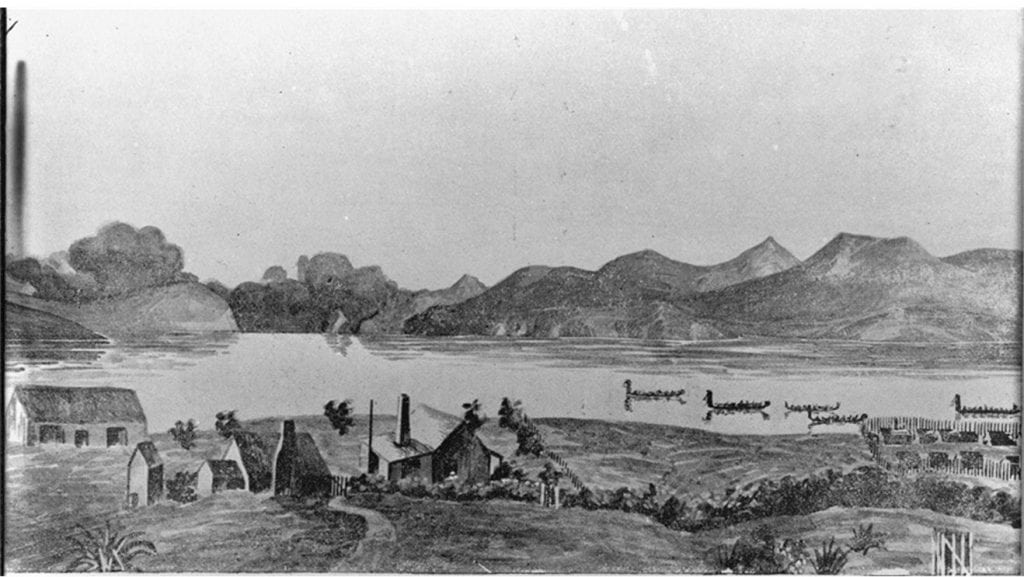

‘Ihumatao Mission Station opposite Manukau Heads, 1855’, by Mrs Forsaith, NZ Map 4-1252, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Furthermore, Pukekawa, Maungakiekie and the Ōtuataua Stonefields reveal a very different colonial Auckland. Historians and the wider public tend to think of colonial towns in New Zealand as ‘neo-Europes’ and focus on connections between New Zealand and Britain. These places, however, show much more textured histories of colonial Auckland. In these landscapes, Māori tribal networks, missionary circuits, Chinese trading practices and Mediterranean connections all operated alongside the structures of the British empire that have preoccupied historians of Auckland.

At Ihumātao, Māori continued to live on their ancestral lands and practice ahi kā well into the colonial period in Auckland, inviting the missionaries into their space on their own terms. For almost twenty years, the Ihumātao mission station and the Ōtuataua Stonefields operated as hybrid places, where missionaries, Māori and local settlers lived alongside each other. Alongside the strict routines introduced by the missionaries and the fixed boundaries set upon the land by the Crown, Māori continued to follow more fluid patterns of existence, moving between their dispersed territories and maintaining their tribal networks. At Ihumātao, the forced evictions of Māori from their ancestral lands on 10 July 1863 created a moment of rupture that had devastating and long-lasting consequences for its Māori communities.

Even in the Auckland Domain, the ‘heart’ of colonial New Zealand, different worlds coexisted in the same space, each with their own notions of identity and place. Just as the governor was establishing botanical and kitchen gardens in the grounds, Potatau Te Wherowhero was moving between his cottage in the Auckland Domain and his other whare (houses) in different locations across Auckland, seeking to forge lasting relationships among tribal groups and between Māori and Pākeha. Tribal leaders such as Ēpiha Pūtini and Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, along with other rangatira, demonstrated an ongoing engagement with the colonial town despite marginalization, and continued operating within their own tribal dynamics and networks alongside European ideas and practices in Auckland.

John Logan Campbell’s olive grove at Maungakiekie was another intricate space where the ideas of Māori, North Americans, Italians and Chinese intersected with the British practices that have been well documented by historians of the nineteenth century. The olive grove highlights the finer, less linear workings of a local community over time, as well as the wider international networks outside of the British empire that often get lost with the teleological lens of history.

View along olive grove in Cornwall Park, 1913. Sir George Grey Special Collections, 4-2490, Auckland Libraries.

The remnants of the Ah Chee market garden beside the Domain, meanwhile, offer glimpses of a Chinese immigrant community that was closely connected with the European settler communities in Auckland, but that also operated within different ontological assumptions, processes and networks.

Ah Chee’s market garden in the process of being ploughed over to convert the site into sports grounds. New Zealand Herald, 19 February 1921, Supplement, p.2.

The Ah Chee family continued to build on these processes after they left their market gardens and have since made a substantial impact on Auckland’s foodways, with the establishment of Foodtown and Georgie Pie.

Chan Ah Chee (centre) with his grandchildren (not dated) PH-NEG-C42317a, Auckland War Memorial Museum.

By delving deeply into specific places and considering the broader questions that arise from them, new historical connections across the city as well as nationally and internationally emerge that are hard to see and understand in more generalised histories. These connections challenge and reframe some of the assumptions that currently underpin understandings of Auckland’s and by extension New Zealand’s history.

An expansive timeframe undermines any simple phasing of the past into clearly delineated periods that historians often work within, and shows how our current moment is inflected by remnants of earlier histories, with different systems and ideas that have been dismantled, rearranged and built upon over time. By entering the landscapes of Auckland, the physical environment also becomes part of the history of New Zealand’s urban spaces. It re-centers the weight and power of geography in Auckland and forces the reader to move away from a tendency to treat the material world as a passive backdrop to events.

Places resist singular stories and triumphant narratives, and instead open up histories, making room for the presences and absences, as well as the voices and silences that are part of this city’s past. Opening up the ground of Auckland’s landscapes uncovers deep and complex histories, at once indigenous, settler and international. These places tell multi-faceted and nuanced stories that need to be understood alongside the more familiar histories of Auckland. They are important stories to tell if we are to know, understand and reckon with this city’s past.

*Lucy Mackintosh is the history curator at Auckland War Memorial Museum | Tāmaki Paenga Hira and has recently completed a PhD in history at the University of Auckland examining the connections between people and places in three historic landscapes: Auckland Domain, Maungakiekie/Cornwall Park, and the Ōtuataua Stonefields. This piece is based on the book “Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland” available here.