Part Two

LAND OF SCORIA AND HONEY: Pioneering Economies on Rangitoto Island

by Blair McIntosh*

On the front page of an 1896 edition of the New Zealand Herald’s Saturday paper, a member of the public writing under the pen name ‘Colonus’ introduced their 2000-word monologue On Rangitoto with the following assertion:

“It does seem strange that while life and industry and enterprise have been for so many years throbbing and palpitating around the shores of the Waitemata Harbour, this great mountain [Rangitoto] should be standing so grimly and gloomily picturesque opposite the doors and windows of fifty or sixty thousand people, without a single mark to show the touch of the hand of civilisation … the hand that would try to reduce the great cinder block to the production of either the utile [useful] or the dulce [pleasant].”

It is important to note that Colonus’ description of Rangitoto Island as a landscape without a ‘single mark’ of human industry or enterprise is deeply misleading. Rangitoto has always functioned as a place of sustenance and economic livelihood for a variety of different communities. Yet, in many other ways, Colonus’ assertion nevertheless reveals how in the eyes of many Aucklanders, the Island’s greater purpose was still waiting to be unlocked. Indeed, throughout much of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, Rangitoto attracted no shortage of enterprising individuals to its shores all intent on reaping the enigmatic Maunga’s promise of lucrative financial reward. As this essay will argue, central to Rangitoto’s economic lure was its perceived location on Auckland’s imagined frontier. It stood as a place that was both ‘out there’, with vast amounts of resources and land yet to be properly exploited but also ‘over here’, still within close proximity to Auckland markets. However, it was this same state of ‘in-betweenness’ or liminality which ultimately limited the chances of economic success and caused many of these pioneering industries to have their hopes of finding an arcadian paradise of ‘scoria and honey’ painfully dashed.

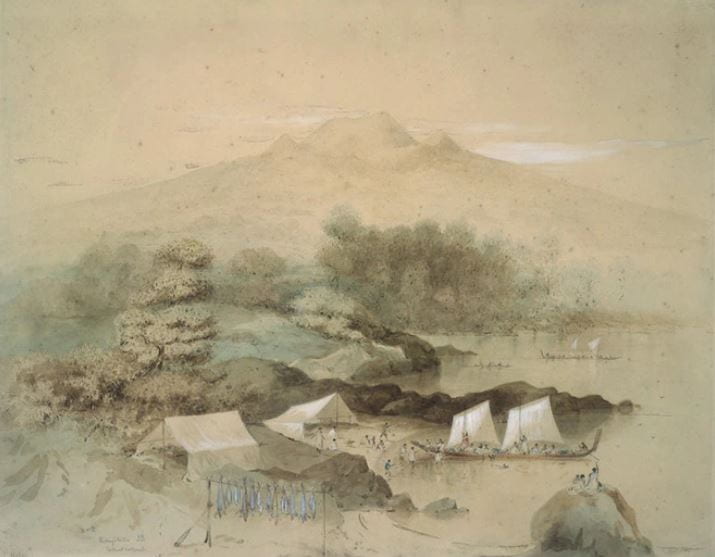

Extinct Rangitoto, watercolour by Charles Heaphy, c. 1857. Depicted in the foreground of this painting is a temporary Māori fishing camp, including two large tents, a fish drying rack and a few fishing canoes. Although Heaphy’s portrayal of Māori activity does need to be considered carefully, since the watercolour was painted from memory five months after his initial journey up the maunga’s summit, it nevertheless is useful for highlighting how expeditions to the Island for harvesting resources were an important activity for Tangata Māori (the Māori people). Image from National Library, Reference C-025-022.

EARLY MAORI ACTIVITIES ON RANGITOTO

The history of economic activity on Rangitoto Island doesn’t start in the late 1800’s with Pākehā notions of commercial potential. For a least a century before then, Māori frequently harvested marine and land-based resources from the Island. One of the most prized among these was the kaka bird, as its feathers could be used to weave impressive korowai (cloaks) or traded with other tribes for items of prestige. According to oral histories of early Rangitoto preserved by Ngati Tai ki Tamaki, the Island’s abundant bird population was protected by the powerful Te Tini O Maruiwi chief Peteru, who viewed the island as his ‘kahui-kaka’ or parrot sanctuary. Alongside bird hunting, fishing and oystering were two other core economic activities conducted on the Island, often harvested on a seasonal basis by all three ropu (groups) who claim mana whenua over Rangitoto. These three ropu include Nga Puhi, a Northland based iwi; Ngati Paoa, descendants from Tainui Canoe who settled in the Hauraki region and Ngati Tai ki Tamaki, whose ancestors include both Tainui and New Zealand’s earliest inhabitants, known as Te Tini o Maruiwi.

Moreover, transcripts from the Native Land Court reveal that Nga Puhi and Ngati Tai likely also cultivated some small plots of kumara on Rangitoto, which was often planted with scoria to protect the kumara from frost and help with drainage. For a more in-depth look at how these three ropu likely navigated their overlapping claims and harvesting of resources on Rangitoto Island, Tommy De Silva’s series of essays on Ngati Atua history serve as an excellent starting point.

SEARCHING FOR WHITE GOLD: SALT MANUFACTURING ON RANGITOTO ISLAND

On August 10, 1890, the Devonport Borough Council succeeded in petitioning the New Zealand Government to hand administrative authority of Rangitoto Island over to its newly established Rangitoto Island Domain Board. Although the Board’s primary aim was to ‘open up the Island as a recreation reserve for the enjoyment of the public’, its members were not averse to ‘opening up the Island’ for the enjoyment of another, more commercially-orientated, segment of Auckland society either. Although several early overtures by some rather colourful personas from Auckland society—including one proposal by Parnell-based doctor SJ Stratford to be granted a lease of the ‘Island of Rangitoto at a nominal rent for nine hundred and ninety-nine years’ to establish a family vineyard and sanatorium (health spa)—were initially declined, mounting expenses associated with developing and maintaining the Island’s rudimentary infrastructure caused the Domain Board to look for new ways of financing its operations.

One of the earliest to be approved was an application in March 1892 for five acres of land on the west side of Rangitoto Island’s foreshore, successfully negotiated by Mr James Stubbs on behalf of the newly-formed Colonial Salt Manufacturing and Refinement Company. Originally a salt merchant from England, Stubbs was determined to be the first domestic producer of salt in New Zealand—especially after the New Zealand government announced it would offer a bonus £1 per ton ($220 per ton at today’s rates) on the production of the first 500 tons of salt made domestically, so long as it was refined by the 31st March 1893. By December 1892 Stubb’s salt manufactory on Rangitoto Island already included four furnaces, a drying shed and several windmills for power generation, and was producing 30-40 tons of refined salt per week. Contrary to what many later visitors to Rangitoto assumed, the salt was not made by simply allowing seawater to evaporate in scoria holding ponds located at ‘Saltpan Flat’ near Mackenzie Bay. Instead, impure rock salt imported from Adelaide, South Australia was mixed with local seawater to produce salt of a higher quality and cheaper yield.

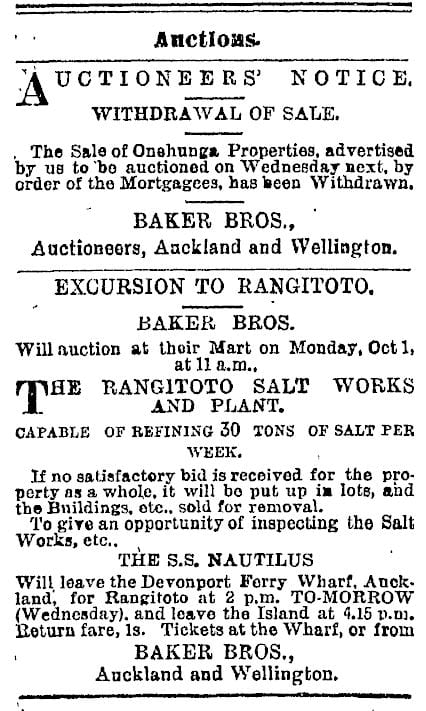

Although the salt refinery was initially profitable (thanks in part to the Government’s generous £1 per ton bonus), the manufactory’s fortunes would soon suffer a heavy blow in February 1893 when a severe storm battered Rangitoto Island and completely destroyed one of the plant’s windmills. Unable to the recover the cost of lost production and struggling to continue maintaining facilities on the Island for the manufactory’s workers, Stubb’s economic venture was at cross-roads. A spike in international rock salt prices caused the Colonial Salt Manufacturing and Refinement Company to finally seek the sale of the salt works operation, attempting to sell the Rangitoto plant on two occasions at auctions held in September and October 1984 respectively. Despite numerous attempts to secure a potential buyer, the manufactory failed to sell, causing Rangitoto’s first and only saltworks operation to gradually fade away into obscurity on the shoreline of Mackenzie Bay.

View of Mackenzie Bay today, overlooking where the holding ponds and panhouse were located.

An advertisement taken out in the Auckland Star for the first unsuccessful auction of the salt works in September 1894 is pictured here. Advertisement, Auckland Star, Volume XXV, Issue 229, 25 September 1894, Page 8. Image of Mackenzie Bay author’s own.

“THE GREAT CINDERBLOCK OF AUCKLAND”

Salt was not the only commodity that enjoyed a brief but intense economic boom on Rangitoto Island. Stone in the form of scoria soon proved also to be a lucrative resource, as the Island which amateur writers like Colonus once referred to as the ‘great cinderblock of Auckland’ increasingly became one. Indeed, as early as 1872 some small-scale efforts to quarry scoria stone from Rangitoto were already being attempted due to the Island’s touted reputation for having ‘an almost inexhaustible supply of superior stone and refuse fit for all purposes’. By 1898, these small-scale endeavours had coalesced into two major mining operations: several quarries under the supervision of the Devonport Borough Council’s Domain Board (which eventually used prison labour for all mining activity—for more information, see my final essay), and the largest quarry in the Southern Hemisphere, owned by the influential Auckland Harbour Board (now known as Ports of Auckland).

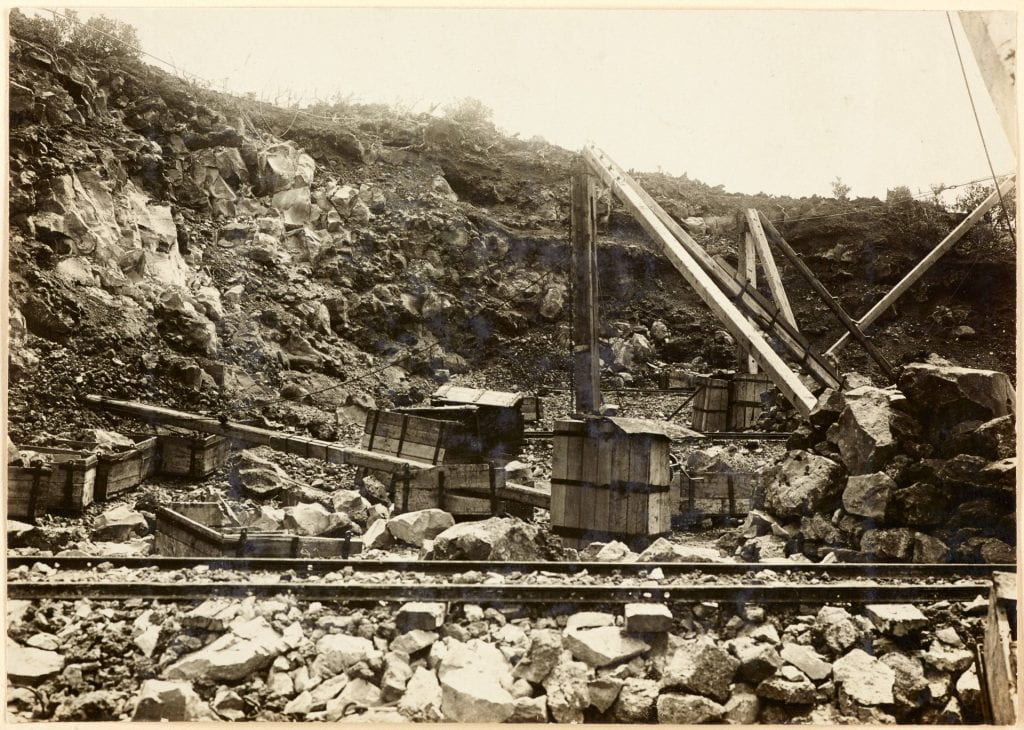

Panorama of Islington Bay Quarry, overlooking the wharf pictured left. In the righthand photograph, a section of quarry face can be seen alongside the trolley carts used to take scoria to the stone crushing plant. Images from Album 43, p 95. Auckland Harbour Board archives. New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa [19232].

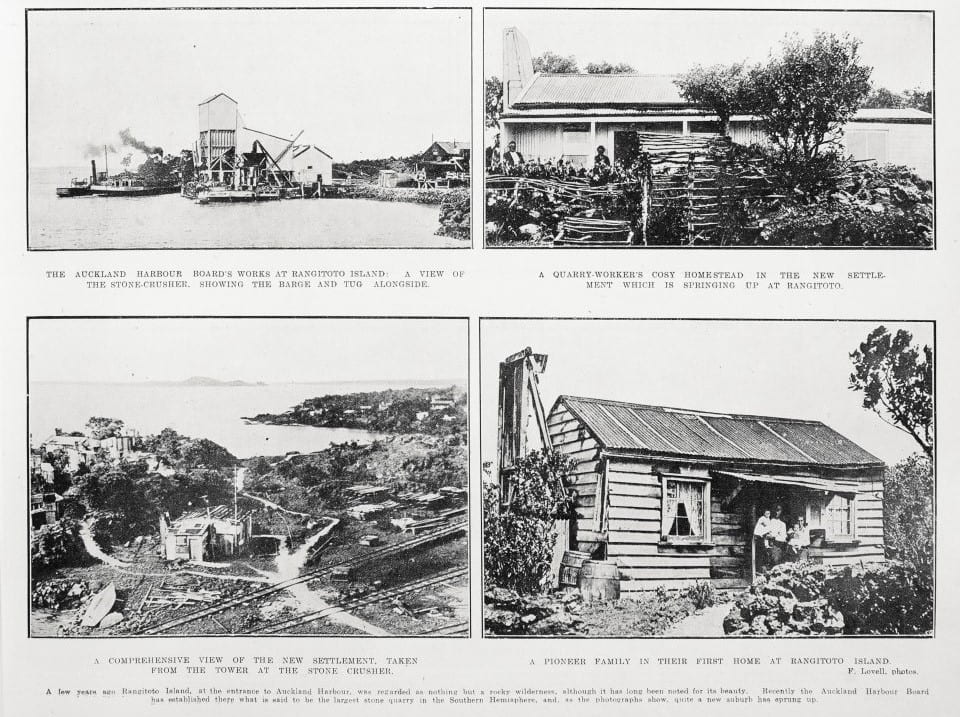

Situated near Islington Bay, the Auckland Harbour Board’s stone quarry covered nearly 60 acres of Rangitoto Island, and at its peak provided employment for up to 100 workers. As part of its mining operation, the quarry featured no fewer than nine hand cranes, two wharves, a stone crushing plant and multiple trolley lines to quicken the delivery of quarried material to dedicated scoria barges at a rate of 200 tons every few hours. From here, the stone (often in the form of cinderblocks or concrete chips) was shipped to Auckland for use across a vast array of building projects, including the construction of some recognisable landmarks like St Matthew’s and St Paul’s Church alongside the Melanesian Mission in Mission Bay. Due to the site’s remote location, the Auckland Harbour Board also built an additional 50 huts surrounding the quarry to accommodate workers and their families, alongside a small library, several gardens and even a ‘Rangitoto Quarry School’ which had 11 students on its roll by 1927. As the arcadian romanticism of one New Zealand Herald article written in October 1922 betrays, life at Islington Bay Quarry still possessed for many Aucklanders the aura of the frontier. It was a place which, as the article’s author opines, could be richly imagined as an ‘Island Paradise’, wherein:

“Lean men with rippling muscles; resourceful wives and sun-browned children, live as gypsies, within nine miles of a bustling city, and yet know the ways and the peace of the wilderness, with wallabies, possums, and wild bees sharing in a splendid isolation.”

Photographs from a section of the Auckland Weekly News on life at the Islington Bay Quarry, showcasing the quarry’s infrastructural progress and new ‘homesteads’ for quarry workers and their families. Many of these would later be turned into baches during the interwar years. Image courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Images, Reference Number AWNS- 19221026-37-8.

STIRRINGS OF TROUBLE ON THE FRONTIER

Although the vision of life on Rangitoto as a place abounding—quite literally—with ‘scoria and wild honey’ was a powerful one, the reality was less idyllic. Quarrying was an extremely hazardous occupation, with injuries from poorly-detonated explosives, falling rocks and machinery malfunctions common. At Islington Bay Quarry alone, six quarry workers were seriously injured (often with fractures to the skull) and two were killed after being crushed to death under falling debris. Receiving only £4 8s per week ($398 at today’s rates), the pay was little for the risk workers incurred. After the hospitalisation of two men with skull, nose and hand fractures in two separate quarry accidents on the same day, public scrutiny of mining operations on Rangitoto began to mount. Indeed, it was not just mining accidents the general public demanded action over. Concerns over continued environmental damage to Rangitoto were raised too. As one of the most vocal critics of quarrying on Rangitoto Island, the Akarana Māori association, decried:

“We consider that it should be the aim of the future to endeavour to protect this island so far as it is possible as a sanctuary for native flora and bird life. The granting of quarry rights in the past has led to the lamentable destruction of this natural beauty.”

Photograph taken of hand crane no. 2, damaged during a severe storm. Headlines from various newspapers regarding worker injuries at Islington Bay Quarry featured on the right. Photograph from Album 10, K32. Auckland Harbour Board archives. New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa [19136]. Headlines taken from Auckland Star, Volume LIV, Issue 260, 31 October 1923, Page 7; Feilding Star, Volume 9, Issue 3655, 25 February 1932, Page 8; and Sun (Auckland), Volume II, Issue 410, 19 July 1928, Page 13.

Some particularly passionate Aucklanders at a public meeting of the Devonport Borough Council took this objection even further, imploring the Council to put a stop to continued mining on Rangitoto for fear it would ‘permanently disfigure’ the Island’s symmetrical and iconic shape. Indeed, by 1929 even the sizeable coffers of the Auckland Harbour Board—which only one decade earlier generated more revenue than the rest of Auckland combined—was not enough to mitigate the spiralling expenses and negative publicity continued mining at Islington Bay brought. After one final plea with the Domain Board to extend their £10 per annum lease for a further 12 months, Islington Bay Quarry ceased operations in early 1930 just as the full effects of the Great Depression were beginning to be felt in New Zealand. Forced to dismantle all quarry structures to prevent their misuse, the scoured landscape of Islington Bay is all that remains to record the contribution of Rangitoto’s largest attempt at reaping from the maunga’s slopes a bounteous harvest of lucrative financial rewards.

WHY RANGITOTO?

“Now and again somebody has…found a lonely hermitage for years at its base, while drawing a precarious livelihood from the waters surrounding it; and from the same waters, the Saltworks people endeavoured to draw as precarious dividends, to be submerged at last by the fate that has seemed to be guarding its lonely shores. Sometimes, too, a crank has come around who would transform its barren heights into a vineyard, or crown its triple peaks with fortresses that would rain storms of fire and hail on any daring marauder that presumed to come within the circuit of its horizon. But all these assaults on its solitary grandeur have had the same fate, and to-day it stands as it stood when Captain Cook first saw it over a century ago, as lonely and as desolate as if it was in the Antarctic zone.”

It is perhaps fitting that the same author who opened this essay with such conviction in Rangitoto Island’s economic promise should also guide us in trying to make sense of why all these ‘pioneering industries’ met such an untimely demise. The questions Colonus raises in his piece are pertinent ones: how could a place with such vast resources and natural endowments continue to defy attempts to permanently operate on its shores? And if these efforts appeared to always end in failure, why did so many Aucklanders keep trying?

Whilst there are no simple answers to these questions, I would argue that critical examination of Rangitoto’s real and imagined position in Auckland can offer up several promising clues. As this wider essay series has sought to demonstrate, Rangitoto has always felt to Aucklanders as a place that straddles what we think of as being both ‘out there’ and ‘over here’. Those who came to the Island in search of commercial success were no exception to this, envisioning Rangitoto as a land where the lucrative rewards of ‘prosaic and progressive enterprises’ synonymous with the imagined frontier coexisted alongside its economically-expedient location ‘within nine miles of a bustling city’.

Yet in many ways, this tantalising state of ‘in-betweenness’ or liminality which drew many entrepreneurial pundits to the Island’s shores was also a financially fraught one. Whilst in theory Rangitoto was as close to the central city as the suburb of Remuera, its geographic isolation ‘out there’ in the Hauraki Gulf without running water, electricity or a road network meant that any major commercial operation not only had to fund their own production costs, but also their own infrastructure, including wharves, maritime transport and company town. With such significant overhead costs, any deviation from the highest rate of return—be it from fluctuating market prices, labour issues or even damage sustained in freak storms like that which occurred to the Island’s salt manufactory—was likely to spell financial ruin. Equally, although Rangitoto has the raw materials and space necessary to make the concentrated development of extractive industries like mining and salt production possible, the Island was not far enough removed from Aucklanders ‘over here’ on the mainland to avoid inviting intense, even injurious public scrutiny into its operations. Simply put, because Rangitoto was not definitively a place that was either ‘out there’ or ‘over here’, many commercial operations on the Island only found themselves burdened with the drawbacks of both.

Whilst the economic promise of Rangitoto representing the proverbial promised land overflowing with material and resource abundance was never fully realised, these economic enterprises nevertheless paved the way for another group of Aucklanders to remake the Island in the likeness of their own (pioneering) self-image.