Part One

Pacific Immigrants in the ‘Greater Ponsonby’ region

by Flynn McGregor-Sumpter*

The three decades following the conclusion of the Second World War saw a significant rise in migration to Aotearoa New Zealand. Pacific Islanders in particular were attracted to New Zealand through a scheme that aimed to address the labour shortages in process work and manufacturing. These low-skill, low-wage jobs were plentiful in the 1960s and 1970s, which resulted in an influx of immigrants to New Zealand, predominantly from the Pacific Islands, in order to fill these gaps in the workforce. This growth in the Polynesian population of New Zealand is represented by the fact that in 1966 there were just over 26,000 Pacific people in the country, and only ten years later the population was close to 66,000. Cook Islanders, Niueans and Tokelauans took advantage of their New Zealand citizenship by enjoying free access into the country, whilst Samoans and Tongans were specifically in demand as workers.

The majority of the job openings that Pacific immigrants took were located in Auckland, so along with it being the nation’s biggest city and also main port of entry, it was natural that most Pacific immigrants settled in Auckland. In these early migration years, many Pacific families resided in Auckland’s central-city suburbs, the region which is often termed ‘Greater Ponsonby’. In the aftermath of the Second World War, “large numbers of the established population of relatively prosperous trades people and professionals” left suburbs such as Freeman’s Bay, Ponsonby and Grey Lynn, as they sought the “comforts and space of Auckland’s expanding suburbs”. As a result, houses in this region were, although often run-down, very accessible. Therefore, Pacific people were attracted to the area with the low rent, the inner-city location and bus connections making it easy to access jobs in factories, hospitals and industry. A further benefit of this central location for Polynesian immigrants was the proximity that Freeman’s Bay, in particular, had to the ships bringing in and taking supplies to and from the Islands. The recent arrivals to New Zealand regularly sent money and goods back to their family in the Pacific, whilst they often received foods such as taro and bananas from their homelands, which provided a large portion of their diet.

Once a strong network of Pacific people was established in these inner-city suburbs, the numbers of migrants to the region only continued to grow. Among Polynesian communities, being close to family is incredibly important to creating a sense of security, so the ability to move to a new country yet remain close to kin networks resulted in the substantial growth of the Pacific population in and around the central-city.

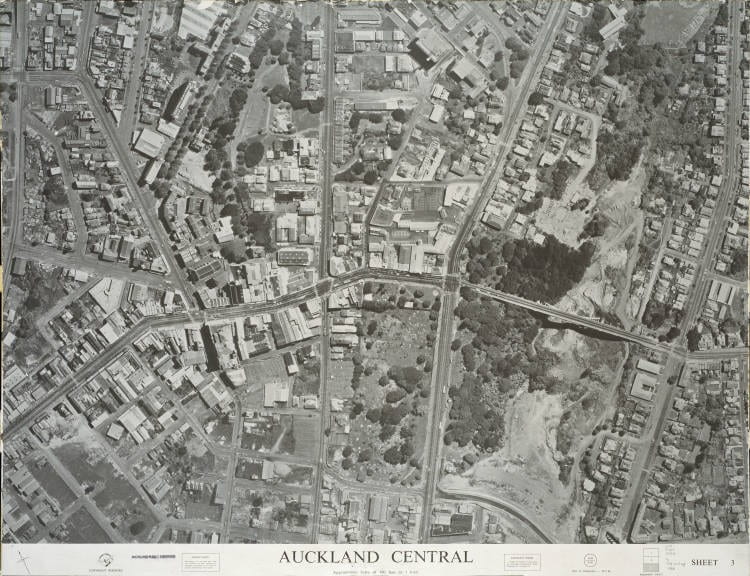

An aerial photograph taken of Karangahape Road (running horizontal from the middle of the photograph to the bottom left) and surrounding suburbs in 1966. Many Pacific immigrants lived on either side of the ridgeline.

The intensification of Pacific Island immigrants in suburbs such as Ponsonby, Grey Lynn, Newton and Freeman’s Bay resulted in there being significant changes to the inner-city. In Freeman’s Bay, for example, by 1966 21 per cent of the population were Pacific Islanders, compared to six per cent of the overall Auckland population. Similarly, Ponsonby was termed ‘little Polynesia’, with 42 per cent of the residents being Polynesian or Māori by 1971.

As one would expect, the adjustment to a new city had its challenges for Pacific immigrants. One of the major issues was housing (as it remains today). The size, layout, and price of the standard central Auckland home was not desirable for Pacific peoples. Many found that “European houses were not big enough for Polynesians, who wanted big rooms where large groups could sit and talk and many guests could stay”. Furthermore, most immigrants could not afford to pay for larger houses to accommodate their needs. As a result of this, by the 1970s many Pacific families were forced into renting, as purchasing their own house in the central city was already beyond their means. This was highlighted through a study taken in 1972 of Tokelaun immigrants living in central Auckland. The survey found that only just over 50 per cent of participants owned their own home. Contrasting this, over 70 per cent of Tokelauan immigrants living in South and West Auckland were home owners. The gap in these statistics reveals that it was already very challenging for Pacific immigrant families to purchase an inner-city house that was suitable to their needs.

Due to the frequency of these housing challenges, a group of Pacific Islanders living in central Auckland, known as the Pacific Islands Housing and Welfare Association, began to give advice on a variety of issues. First and foremost, they aimed to “advise and help Islanders and other citizens on housing”, which included the best practices for buying, selling, leasing or renting a house. Second, they wanted to help immigrants get professional advice in their own languages. Third, they helped Islanders and other citizens with welfare and financial matters. And, lastly, the group aimed to teach Pacific Islanders about the law in New Zealand, with the desire to help them settle into New Zealand society seamlessly. Whilst these issues did not disappear, the influence of such groups portrayed the changing identity of those residing in inner-city Auckland. Pacific immigrants became very adept at helping each other out in their newly formed community, which went a long way to solidifying the central suburbs of Auckland as a place where Polynesians could express themselves and fit in incredibly well.

A second example of the changing face of ‘Greater Ponsonby’ was the significant shift in the makeup of local schools. A number of primary and secondary schools in the area started gaining large numbers of Polynesian students, so much so that in some schools the majority of students did not have English as their first language. For example, at Newton Central School in the mid-1970s, more than 90 per cent of the school roll was made up of immigrants, and English was taught as a second language to most students. Moreover, at Auckland Girls Grammar School, “An increase in Polynesian students pushed up the percentage of non-European girls from 23.5 per cent in 1971 to more than 80 per cent by the mid-1980s”.

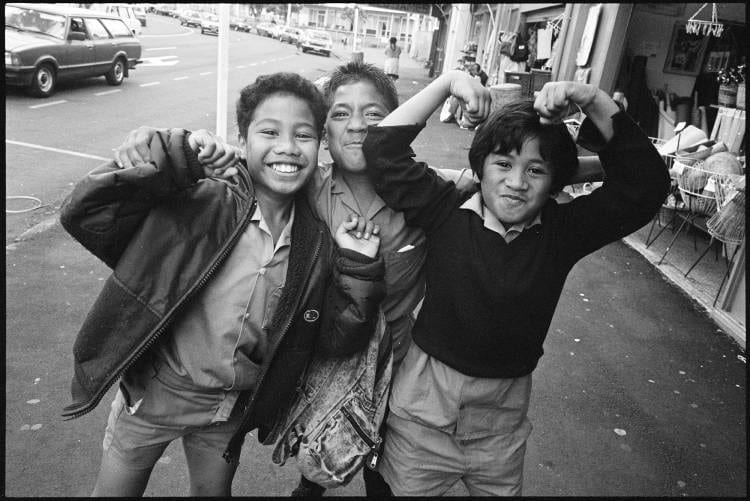

School children on Great North Road in Grey Lynn

Over the course of two decades Pacific culture became dominant in this inner-city region. Pacific Island churches, clubs, and shops selling Polynesian artefacts, clothing and produce became increasingly evident. Local greengrocers in ‘Greater Ponsonby’ in the 1960s and 1970s stocked taro, bananas, coconuts and breadfruit. Furthermore, some families even grew taro and bananas in their backyards, whilst some kept chicken and pigs. Traditional feasts, where extended families would congregate and Polynesian music would be played out through the streets, were regular occurrences and part of the changing inner-city scene. Pacific culture thus began to dominate suburbs such as Ponsonby, Grey Lynn, Freeman’s Bay and Newton in the latter half of the 20th century, with Polynesian immigrants remaining true to their culture and identity.

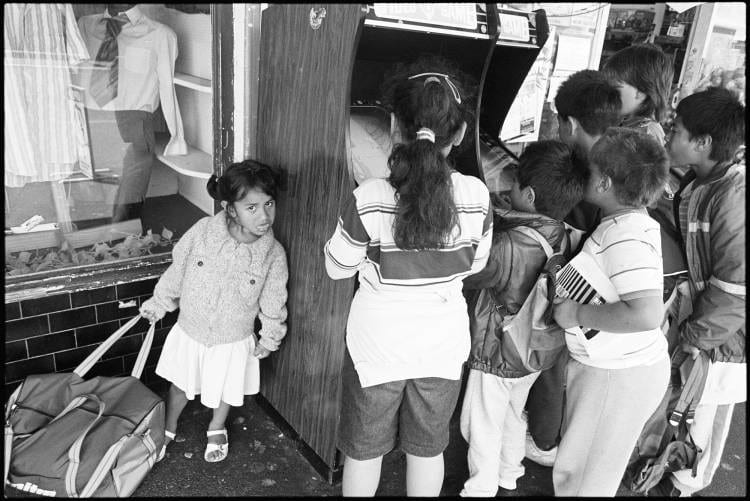

Local children playing an arcade video-game on Great North Road in Grey Lynn

With so many Pacific Islanders making these central Auckland suburbs their home, Karangahape Road became a “mecca” for Pacific peoples. K’ Road quickly became ‘the place to be’, especially on a Thursday late shopping night when Pacific Islanders, both young and old, would shop, talk, meet and hang out with their friends “in true Pacific fashion”. The emergence of Karangahape Road as a significant place for Polynesians began in the 1960s. As they lived nearby, they shopped on K’ Road and started businesses, selling clothing and fruits and vegetables. In the 1970s, the street was filled with Pacific Island shops, with bananas and taro spilling out onto the pavement, and colourful clothing all over the place.

It is important to note that Karangahape Road had also been a place of significance for Māori before colonisation. K’ Road was the only street in central Auckland with a Māori name until the middle of the 20th century, due to the fact that it’s path predates European settlement. The Karangahape Road and Great North Road ridges were used as a walking route by Māori to reach Manukau Harbour – hence the translation of Karangahape to ‘the winding ridge of human activity’, pertaining to the fact that the ridge was a major walking route for more than six hundred years. It was quite fitting, then, that K’ Road became a place of significance for the recently-settled Pacific immigrants.

Reflecting the fact that Karangahape Road was such a key location for Pacific people in more recent times was the construction of Samoa House on K’ Road. This building was the flagship of the Samoan community, and having it on Karangahape Road reveals the strong Samoan presence that was evident in and around the central suburbs. K’ Road became a central space for newly-arrived Pacific immigrants in Auckland. Many Pacific families lived just off the Karangahape/Great North Road ridgeline in the surrounding suburbs of Newton, Freeman’s Bay, Ponsonby and Grey Lynn. Their influence on Karangahape Road itself greatly strengthened the notion of the street being a landmark in Auckland, and whilst this Pacific presence did not last, it certainly started the diverse history of K’ Road in the latter decades of the 20th century.

An aerial photograph taken of Great North Road (running from top right to bottom left) in 1974. Many Pacific immigrants lived on either side of this ridgeline.