Part Three

The ‘right’ way to be a feminist: conversations on the Contagious Diseases Act 1869 and the feminist consciousness of late nineteenth-century Auckland.

by Saana Judd*

The Auckland Women’s Liberal League’s support of the controversial Contagious Diseases Act 1869 (C.D. Act) was a source of outrage among many New Zealanders. The League’s support of an Act that attempted to combat sexually transmitted diseases by examining female sex workers was provocative in a society that regarded state regulation of prostitution as immoral. So contentious was the Liberal League’s position that they were accused of being “the only body of women in the British empire that [had] ever passed such a resolution”. The level of criticism the Liberal League received for endorsing the Act, in contrast to the support the Auckland Women’s Christian Temperance Union (AWCTU) and Auckland Women’s Political League (AWPL) received for opposing it, reveals how there was undoubtedly a ‘right’ way of being a feminist in late nineteenth-century New Zealand. Whilst feminists were defined by their fight for gender equality and autonomy for women, equally important was the pursuit of social purity through Christian values. The failure to advocate for social purity was an example of feminism done ‘incorrectly’, as demonstrated by the criticism the Liberal League received for supporting the C.D. Act.

Criticism at home and abroad

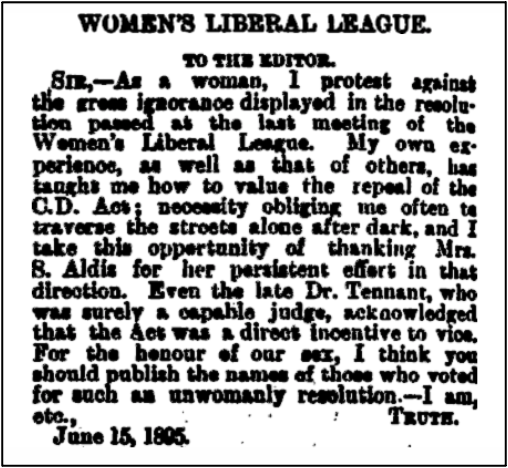

Following the Liberal League’s endorsement of the C.D. Act, newspapers throughout New Zealand were bombarded with letters from the public ardently criticising the League’s resolution. Particularly prevalent was rhetoric implying that the League must have been severely misinformed about the true impacts of the Act. The Liberal League was accused of being “foolish and hasty” and “sadly misled”, with its members displaying “utter ignorance” and “evidently [knowing] very little about” the C.D. Act. The public criticised the Liberal League for supporting an act that “encourages prostitution, leads to the spread of disease, insults womanhood, and defies the law of God”. While a small subsection of society supported the Liberal League – including prominent politicians and some from the medical field – the vast majority demanded that they retract their statement immediately. One woman claimed that “all the liberal women of New Zealand have to bear the blame for what was really done by a small body in Auckland”, while another asked the New Zealand Herald to “publish the names of those who voted for such an unwomanly resolution”. This sense of outrage and disappointment that a feminist group could vote for such an Act was also felt overseas.

Letter from an anonymous women criticising the Liberal League’s position on the C.D. Act. Source: “Women’s Liberal League.” New Zealand Herald, 19 June, 1895. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH18950619.2.59.5

The Liberal League’s resolution was a point of scandal among feminists in Europe. Like the condemnation the Liberal League received domestically, criticism from overseas emphasised the supposed ignorance of the group. In a letter addressed to the Auckland Star – a paper in favour of repealing the C.D. Act – the Women’s Liberal Association of Bristol stated that the Liberal League’s position must be “the result of ignorance” as it was unfathomable how a feminist group could support a “cruel and one-sided law enforced on the poorest and most helpless class of citizens”. Similarly, the AWCTU received a letter from a suffragist in Switzerland “deploring the action of the [Liberal] League and asking for their address that they might send some literature on the subject”.

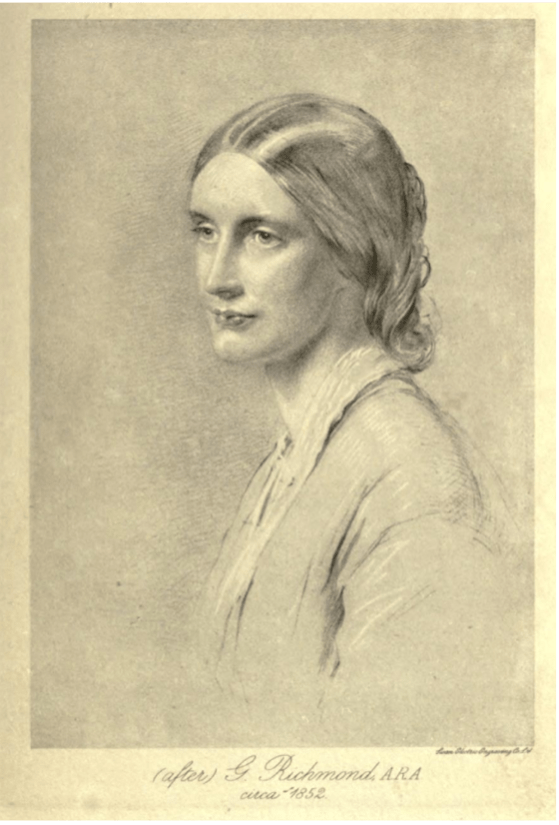

However, the most prominent critique from overseas was that the Liberal League had not been wise in its use of the recently won franchise. Writing in response to the League’s resolution, British feminist Josephine Butler, who led the campaign to repeal the C.D. Acts throughout the British Empire, urged New Zealand women to use their vote to “demand the repeal of a law which is an insult to women”. Butler stressed that it would be a “subject of self-abasement as women if it could be said throughout the world that the first group of Anglo-Saxon women who possessed the vote had failed to use it in this great purifying work”.

Portrait of English suffragist Josephine Butler by George Richmond. Source: Johnson, George W., and L. A. Johnson. Josephine E. Butler: an Autobiographical Memoir. Bristol: J W Arrowsmith, 1909.

While the Liberal League received extensive condemnation at home and abroad, the place from which criticism was most expected was the AWPL and AWCTU. The AWCTU, which was particularly enraged at the Liberal Leagues position, expressed “extreme regret that any society of women should favour the re-introduction of the C.D. Act”. In response, the AWCTU pledged that it “would leave no stone unturned until the disgraceful acts are swept from the statute books” and invited the Liberal League to discuss their controversial resolution at the Union’s next meeting. Taking a similar stance, the AWPL was deeply opposed to and disappointed at the League’s position. After being mistaken for the Liberal League by a woman in Dunedin, the AWPL sought to make it clear that they had “nothing whatever to do with the resolution favouring the C.D. Act”.

Similar, yet different.

Despite the criticism the Liberal League received, their support of the C.D. Act and the repeal campaign led by the AWCTU and the AWPL share a great deal of similarity in principle. Most obvious was the fact that both campaigns centred on achieving equality for women. For the Liberal League, achieving equality meant amending the C.D. Act to make medical examinations apply to both men and women. Contrastingly, the AWCTU and the AWPL desired to achieve equality by abolishing the C.D. Act entirely and instating a new law that would impose a single standard of morality for both sexes. While these two positions have conflicting ideologies behind them, they are both guided by the desire to remove the sexual double standard in the C.D. Act and achieve gender equality under the law.

In addition to equality, the Liberal League, AWCTU, and the AWPL all shared the desire to protect women. The AWCTU and the AWPL wanted to protect the bodily autonomy of women by repealing an Act that gave police the power to order invasive medical examinations. The Liberal League, on the other hand, wanted to protect women from unknowingly contracting harmful venereal diseases from their adulterous husbands. Ultimately, the shared desire to achieve equality and protect women made the Liberal League, AWCTU, and AWPL all worthy of the title ‘feminists’. Despite this, the Liberal League’s stance on the C.D. Act was still criticised as “unwomanly” as it did not support ideals of social purity. The sheer extent of the pushback the Liberal League received suggests that they were no longer a ‘true’ feminist group in the public’s eyes. If this is the case, what does it tell us about the state of feminism in late nineteenth-century Auckland?

Feminism done correctly?

The criticism the Liberal League received for its support of the C.D. Act reveals the prevalence of Christianity in the feminist consciousness of Pākehā women in the late-nineteenth century. At that time, feminism in New Zealand was focused on the demand for autonomy and equality for women. However, with over 90% of Pākehā being Christian, feminism was also heavily influenced by Christian moral values. Many Christians believed women were the “moral guardians” of society, making it a woman’s job to achieve the Christian ideal of moral purity. As such, to empower women would be to enhance the moral purity of New Zealand.

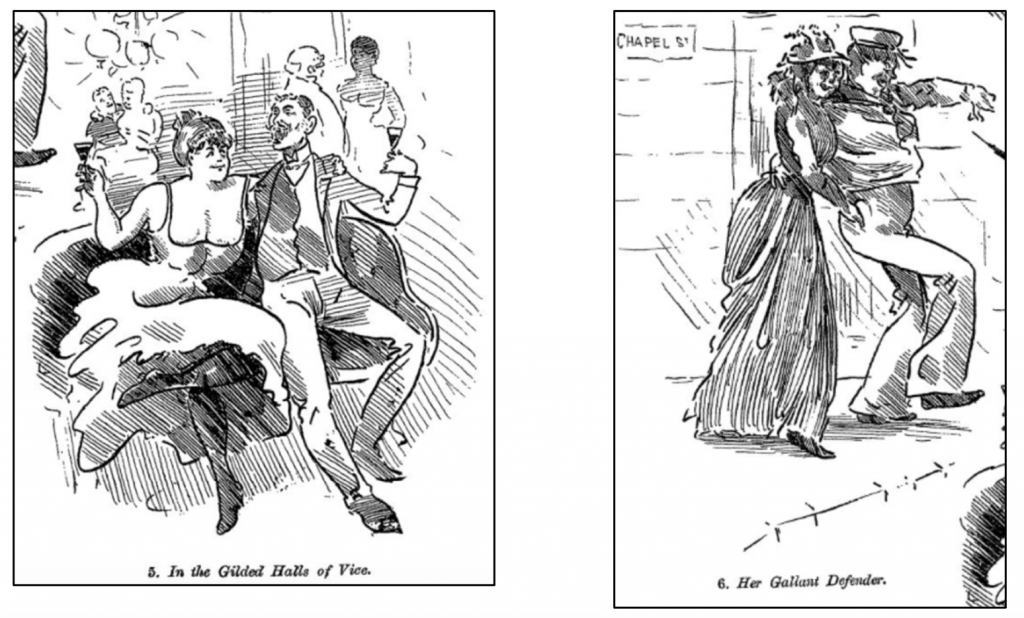

Adopting this position, many feminists aimed to rid society of ‘impurities’ such as alcohol, gambling, and prostitution. The Liberal League’s support of the C.D. Act – a law that regulated prostitution – was therefore condemned as an action that “insults womanhood and defies the law of God”. The public’s outrage that a group of women could possibly hold this perspective suggests that the Liberal League had violated commonly understood conditions of feminism. Despite the intention of the Liberal League to promote gender equality and protect women – ideals that were shared with the AWCTU and AWPL – they were not seen to be ‘doing’ feminism correctly as they did not promote the idea of social purity. Clearly, feminist intentions alone were not enough to be a ‘correct’ feminist. Rather, the ‘right’ way to be a feminist in nineteenth-century New Zealand involved fighting for women’s rights while also pursuing Christian values of moral purity.

1889 cartoons by William Bloomfield detailing the ‘social evil’ of prostitution. Source: Blomfield, William. “The Seven Ages of a Lost Sister”. New Zealand Observer and Free Lance, 12 October, 1889. H-713-095. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. /records/22306446

Has anything changed?

The idea that there was a correct way of ‘doing’ feminism in New Zealand during the late nineteenth-century calls into question the state of feminism today. Specifically, it challenges us to question whether there is a ‘right’ way to be a feminist in the twenty-first-century? In some ways, the rigid religious rules around feminism are no longer prevalent. Christian values of social purity no longer dictate what it means to be a feminist in 2022. On a basic level, being a feminist today means demanding equality with men, as it did for all three feminist organisations of the late-nineteenth century. However, beyond that, there still exists a series of unwritten assumptions about what a feminist must be. Western culture tells us that feminists should not be overly concerned with their appearance, they should strive to be more than mothers or wives, they should be liberal and progressive, they should oppose pornography, they should not shave their body hair. The list goes on.

In many ways, the criticism the Liberal League faced for supporting the C.D. Act mirrors the situation many self-proclaimed feminists find themselves in if they do not correctly follow these prescribed rules of feminism. However, despite these rules, it is true that what it means to be a feminist has become increasingly fluid since the late-nineteenth century, as seen in the support of New Zealand feminists for the decriminalisation of sex work. Although the details of the C.D. Act remain controversial, had the Liberal League existed today, their support for state regulated prostitution would align closely with contemporary feminism in New Zealand.

Conclusion

Following universal suffrage in 1893, local female political groups played an important part in advocating for the rights and interests of women in New Zealand. This is particularly true in Auckland, where the Auckland Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Auckland Women’s Political League, and the Auckland Women’s Liberal League all campaigned to achieve gender equality in marriage, divorce, employment, and healthcare. However, it was the topic of venereal disease and the Contagious Diseases Act 1869 which dominated much of the feminist debate in late nineteenth-century Auckland. A controversial and divisive topic, the contrasting opinions of the AWCTU and the AWPL on one hand, and the Liberal League on the other, revealed a significant split in the feminist consciousness of Auckland women at the time.

However, it was the zealous criticism that the Liberal League received from all sectors of society – both in New Zealand and abroad – that revealed the presence of a dominant feminist narrative at the turn of the twentieth-century. Behind this narrative was the idea that socially ‘correct’ feminism must go beyond the pursuit of equality for women. Rather, the ‘right’ way of doing feminism also involved the promotion of social purity through Christian ideals. Whilst the association of feminism with religion has largely eroded away in New Zealand, unwritten rules still quietly dictate what it means to be considered a ‘true’ feminist in the twenty-first century.