Part Two

Swimming in Onehunga: a long journey to the pool

Part Three

Jellicoe Park: a green space of remembrance

by Gretel Boswijk*

Swimming is part of Auckland life, in the sea or at one of the public swimming pools scattered across the city. Some of these pools, such the Parnell Baths and Tepid Baths on the north side of the Tāmaki isthmus have been operating for over 100 years, and have been written about. However, it appears that there were few public swimming pools on the south side of the isthmus until the opening of the Onehunga War Memorial Swimming Pool in 1956. Recently I investigated the origins of this swimming pool for Masters dissertation on living memorials. As the name suggests, it was built as a post-World War II (WWII) war memorial, but exploration of its history shows it was a product of long held desires for a swimming pool in the borough and was part of a wider trend to providing swimming facilities across Auckland during the first half of the 20th century. This short essay outlines the long journey to the opening of the Onehunga pool.

Writers such as Caroline Daley and Annette Lees show how swimming became popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. At Onehunga, people could swim at the beach, although the tidal range of the harbour would have limited bathing to the hours around high tide. The local swimming club held carnivals at Onehunga Wharf until the 1910s when they relocated to swimming baths on the north side of the isthmus. The popularity of swimming in Onehunga is evidenced by a 1915 New Zealand Herald report that over 350 women had signed a petition calling for improved bathing sheds at Onehunga Bay and that some ‘200 or more [women bathing] in the water at once is a common sight’. (The women also asked that the council forbid horse owners from swimming their horses when and where the ladies were bathing.)

Sea swimming aside, there was a strong desire from the 1890s onwards for a swimming pool in the Borough and the subject was often raised at council meetings. (Some Onehunga Borough councillors were also members of the local swimming club.) A local pool would offer a safe alternative to sea swimming, provide a space to learn water skills, and support club activities. Various plans were put forward. In 1919, councillor T. W. Morton suggested that a swimming bath should be part of the new war memorial park at Onehunga Domain (now Jellicoe Park). In 1926, the borough council considered a plan for a war memorial park at Geddes Basin which included a saltwater pool, and in 1931, contemplated a (freshwater) swimming pool at the site of natural springs by the Onehunga Railway station.

In between, in 1929 the Auckland Harbour Board granted permission for new bathing sheds and a large saltwater pool (50 yards (45 m) square) to be built at the foot of Normans Hill, the site of the current Onehunga Lagoon (Figure 1). Work on this began in 1933 with construction by relief labourers as part of a wider beach improvement scheme. The concrete tank would fill by tidal flow but permitting swimming at any time during the tidal cycle, and it was anticipated to be in use by summer 1934-35. Whether it was completed remains a mystery. No report of its opening was found and there is no sign of the pool in the modern landscape, overwritten by more recent alterations to the foreshore and road.

Figure 1: View of Onehunga Bay at the junction of Esplanade and Normans Hill Road, looking south towards Mangere Mountain, ~1927. Unroofed Ladies and Gentlemen’s changing sheds are on the foreshore by the beach. The saltwater pool was built in this area. Photograph by E.D. Pritchard, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 36-P50B.

By 1938 the council was again discussing provision of a swimming pool for the borough and the following year, engineer, Mr. R.D. Baker, reported to council:

‘that the plans and specifications for the proposed swimming pool in Trafalgar Street, adjoining Jellicoe Park had been placed before the Local Bodies Loans Board for its approval to place the loan proposal for the pool before the ratepayers.’

The pool would be 100 ft long by 60 ft wide (30 m x 18 m), with dressing sheds, flood-lighting and underwater lighting. It would be heated by electricity and the design included space for sunbathing on the roof of the building. But it never got beyond plans, perhaps due to cost and the disruption of WWII.

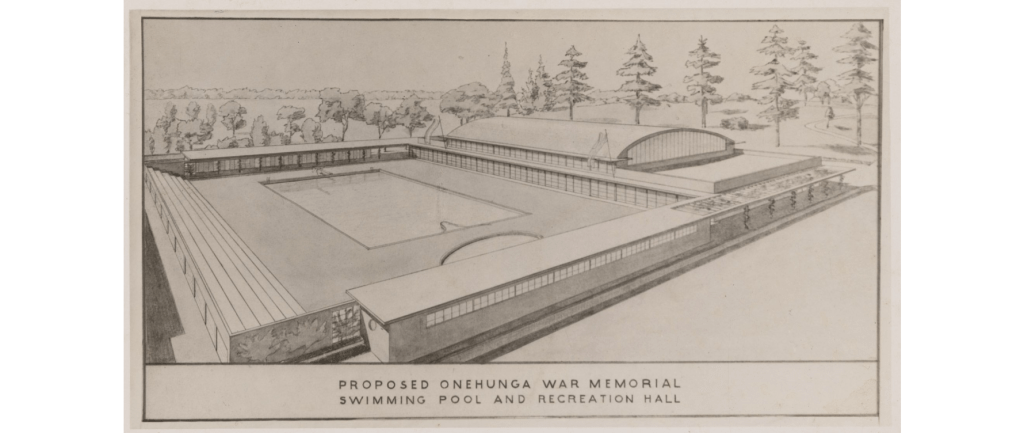

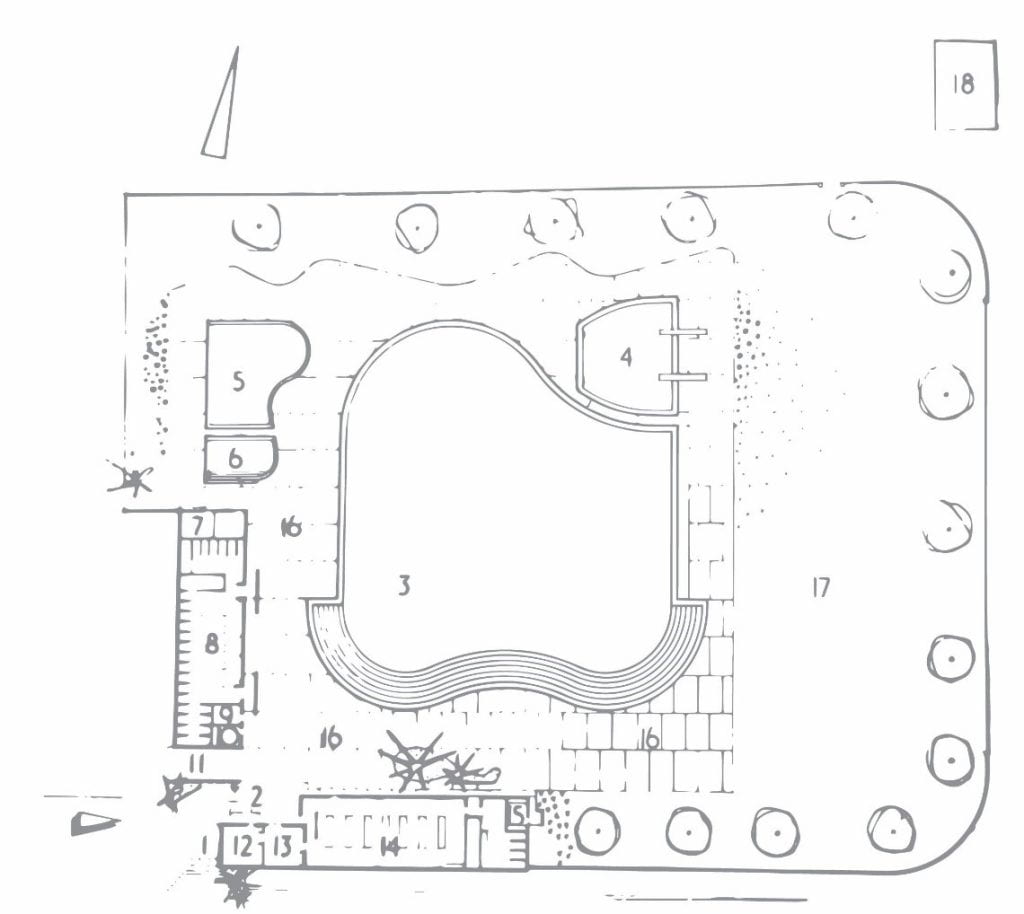

A new plan for a pool resurfaced in 1951 as a utilitarian (or living) memorial adjacent to Jellicoe Park, itself a World War I (WWI) War Memorial Park. An architect’s drawing shows a large rectangular outdoor pool situated in an expanse of concrete and with a glass fronted hall on the south side (Figure 2). The final version that was built, designed by architects Mark Brown and Fairhead, lost the hall and presented a new free-form lido-style swimscape to Onehunga and New Zealand. Its curves evoke the British lidos of the 1920s and 1930s (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Proposed swimming pool and recreation hall adjacent to Jellicoe Park, Ashe Photograph, 1951. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 957-403.

Figure 3: Reproduction of an architect’s sketch drawing of the complex included in the 1956 Opening Day brochure.

The provision of a public swimming pool in Onehunga fit within civic improvement schemes, adding to recreational facilities within the Borough. Additionally, the creation of a swimming pool aligns with wider conversations about the provision of swimming facilities by municipal authorities in the Auckland region, particularly from the 1930s onwards.

Swimming pools provided bounded, safe and controllable spaces for swimming but in the early 20th century their location was biased to the Waitematā coastline, with coastal pools at Shelly Beach (lost to the motorway and replaced by Point Erin baths) and Parnell, and the covered Tepid Baths between. On the North Shore, a large swimming bath was proposed for Hinemoa Park, Birkenhead and Milford’s ‘Great Wonder Pool’, reportedly the largest in New Zealand (now the Milford Reserve) opened with great festivity in December 1936. A sea-pool was even built on Rangitoto Island, serving the bach community there. The opening of the Olympic Pool at Newmarket in 1940 filled a gap in public swimming facilities in central Auckland. In between, school ‘learner pool’ proliferated across the regions, giving children necessary water skills. The completion of the Onehunga Pool in 1956 provided safe summer swimming for the south side of the isthmus (Figure 4). Although the buildings have been modified and the complex expanded with the addition of indoor pools since the late 1970s, the outdoor pools are still in operation. They are like a blue oasis offering water-based fitness, recreation and wellbeing amidst the suburban landscape.

Figure 4: Looking west over the Onehunga War Memorial Swimming Pool, Onehunga, in 1956. Whites Aviation Ltd: Photographs. Ref: WA-43849. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/32052216