Part One

Opening the Door to the Private Spaces of Auckland’s Queer Communities

by Frederike Voit*

Stepping out of one world

And into another that’s

The way it seems

But I don’t care what

Others might say –

That’s the way I

Want to be

T.

In 1986, the Homosexual Law Reform Act legalised sex between men aged sixteen and over. This law change was the culmination of a decade and half of political discussion, and had mobilised New Zealanders to voice their opinions on homosexuality in over 1100 submissions to the Justice and Law Reform Select Committee. In light of this intense popular and media attention – which also coincided with the country’s first cases of HIV/AIDS in 1984 – Homosexual Law Reform may seem like a natural starting point in telling the story of New Zealand’s queer communities. These communities, however, did not come into existence the moment they were exposed to public scrutiny. The world that journalists, politicians, and everyday people stepped into in the 1980s was a well-established one, which had long found expression in a network of queer spaces.

Auckland, in particular, was believed to have “the largest gay population of any city in New Zealand,” and accordingly also many queer spaces. This was a fact that queer people were intensely aware of, recognising that Aucklanders “are prone to complacency, when you and your lover can easily … take off to the pub.” The city’s queer pubs and clubs also attracted those who lived further afield, with people visiting from as far as Paparoa in Northland. An exploration of queer spaces from the 1950s until the turbulent mid-1980s thus reveals the lively presence of queer people in Auckland at this time as well as the active role of the city in shaping their lives.

Despite their centrality in the history of Auckland’s queer communities, these spaces were often hidden, transient, or – as is the focus of this article – private. Likewise, the people who occupied them often only appear in sources by first names or pseudonyms. In light of these challenges, the four articles comprising this project are not a comprehensive survey of significant locations and people, but rather a thematic series of insights into the types of spaces that queer Aucklanders inhabited. While I use the word queer as an all-inclusive term for these groups, it is, of course, anachronistic, and individuals are referred to by the labels they themselves preferred.

The problems of queer people in private spaces

Most private homes in mid-twentieth century Auckland were not havens for queer people. The broader societal discrimination experienced by the city’s queer communities inevitably filtered down into these spaces. Actual or anticipated rejection by family members was a particular concern, leading many queer people to hide not only their sexuality, but also interests, friends, and partners during their youth. Even in adulthood, housing insecurity followed queer people throughout their lives. Section 146 of the Crimes Act 1961, which was later repealed with Homosexual Law Reform, outlined penalties of up to ten years’ imprisonment for “keeping a resort for homosexual acts.” This section was regularly employed by landlords to evict tenants suspected of being queer. Others were only protected by their landlords’ and neighbours’ ignorance. This was the case at a New Years’ party hosted by Les Mack at his Parnell flat, complete with drag performances and dancing. The next day, “the elderly neighbour … said to the owner of the house, ‘it was so lovely to see your tenants enjoying themselves, they played charades all night!’” Here, as elsewhere, safety depended on secrecy.

In addition to external threats such as eviction, many queer people felt conflicted in private spaces because they rejected the conventional aspirations of home ownership and a nuclear family. This was particularly prevalent among self-identified ‘lesbian-feminists’, who were active in second-wave feminism during the 1970s and 1980s. One such woman, Julie, questioned whether buying a house was too “capitalist” before making the investment. Another, writing anonymously because of an ongoing child custody dispute, emphatically condemned “the oppression of women through … the nuclear family.” Internally as well as externally contested, the private spaces of Auckland’s queer community were the site of significant challenges.

The solution: establishing queer homes

Without minimising these challenges, I choose to instead foreground the ways that queer communities – quite literally – made themselves at home in Auckland. This typically involved living with other queer people. In earlier decades, couples often quietly moved in together, aware that they “had to be very careful because … there were always questions.” These questions, however, were not an insurmountable barrier. Some who wanted to do so even succeeded in establishing queer families, for example through whāngai (adoptions within whānau). Shirley Tamihana was one woman who raised a family this way, fostering two children of her female partner’s sister in a house that also, at various times between 1973–77, included the children’s birth mother and five other children.

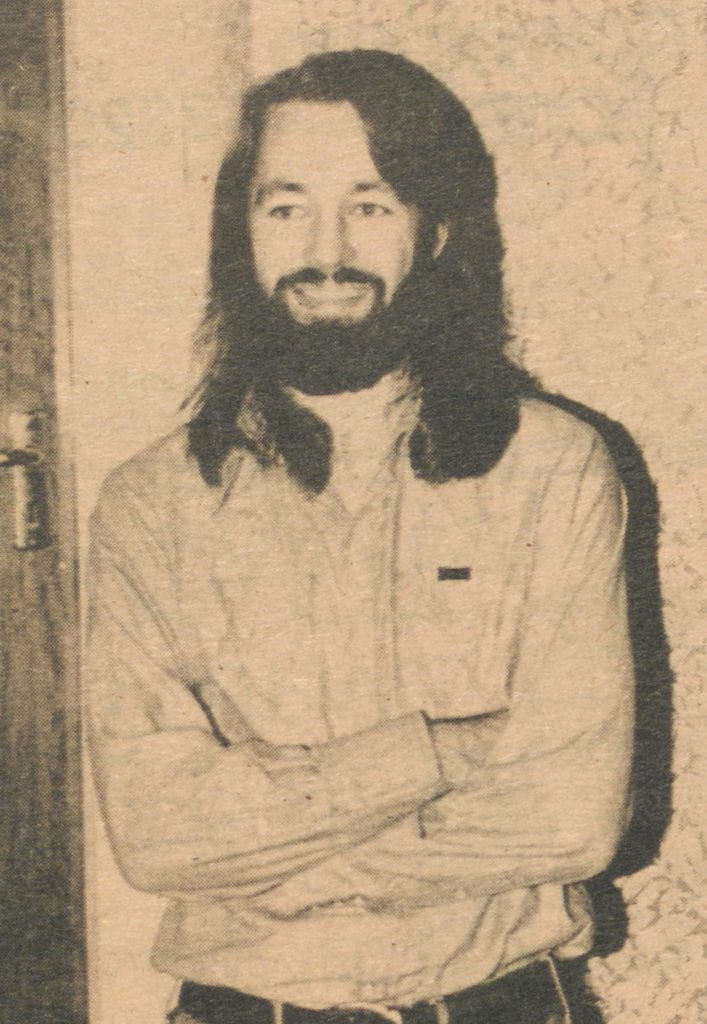

For others, the move from non-queer to queer-dominated private spaces was bridged by transitional housing arrangements. It was not unusual in the 1950s and 1960s for younger people or those not in relationships to spend time in boarding houses. This remained a popular pathway as hostel options diversified in the 1970s. In 1971, for instance, the Youthline Hostel on Lloyd Ave in Mt Albert was established by Felix Donnelly, Youthline co-founder and a Catholic priest. While the hostel was never an exclusively queer space, Donnelly – later a vocal proponent of Homosexual Law Reform – was “often having to place gays who’ve been evicted.” Lloyd Ave thus became a formative place for queer Aucklanders like David Russell, a Gay Liberation activist who stayed there shortly after moving to Auckland. “Felix Donnelly’s place … helped me to accept myself and come to terms with my sexuality,” as Russell attested.

Felix Donnelly (left) and David Russell (right), who were both associated with the Youthline hostel.

Over time, the most widespread and stable living arrangement for Auckland’s queer communities became flatting. This was a subtle shift: queer people sharing flats was certainly not new, and nor was it a lifestyle adopted by everyone. Yet what had begun as a necessity gradually transformed into a cultural phenomenon. Queer communities were beginning to organise politically during the 1970s and 1980s, with the first Gay Liberation groups arising in Auckland in 1972, and an echo of this new collective consciousness is seen in the desire to live collectively. Frankie, a woman who decided to leave her suburban Auckland house for a flat in 1983, did so because “my social needs of talking to other lesbians are not being met.” She was far from alone. A network of queer homes emerged in the city’s central suburbs, notably Ponsonby, Grafton, Grey Lynn, and Herne Bay. These houses were busy and dynamic spaces, advertising regularly for new flatmates. Indeed, one flat on Franklin Rd in Ponsonby was, from 1983-4 alone, home to Louise, Judith, and Jenny, likely also Hezzie, Sala’am, Lizzie, and Sarita, and many other women.

Location of the queer flat on Franklin Rd, January 2023. Photo by Friederike Voit.

Franklin Rd also exemplifies the clear and consistent division between lesbian and gay households. Indeed, advertisements for a “mixed gay/straight flat” were more common than for ones jointly rented by lesbians and gay men. This reflects the fact that these groups only began to understand themselves as having a shared identity beyond the 1980s. The common belief at the time that “homosexual men and women [strive] for different things,” including Homosexual Law Reform and women’s liberation respectively, thus translated into separate domestic lives. Yet with the exception of some lifestyle differences – including the tendency of lesbian households to prefer vegetarian flatmates – the similar patterns of shared housing in gay and lesbian communities do suggest a degree of shared social experiences.

This is not to say that all queer Aucklanders lived the same way. Naturally, these people were diverse and multifaceted, organising their lives according to more than just their queer identity. Houses were sought and offered for various timeframes, from advertisements for “people interested in buying a house” to one gay man’s offer of “accommodation for weekends [when] you are visiting Auckland.” Location, too, mattered: Nick, a nineteen-year-old student, specifically searched for a gay flat close to the university campus. These differing priorities, amongst many others, hint at the diverse lives which were lived in Auckland’s queer homes.

Stepping into a lesbian household on Wallace St

Location of the lesbian flat on Wallace St, January 2023. Photo by Friederike Voit.

The flat on Wallace St was considered unique even when it was established in early 1982, due to its exceptionally large size. A ten-bedroom Herne Bay house became home to ten women, one child, and several animals. This made it a subject of public interest in the lesbian community, with other women commenting that it was “great that a bunch of you have got together [to do] the communal thing in larger style.” This, indeed, was another factor that set Wallace St apart: it sought to apply the lesbian-feminist principles of shared labour and communal resources to a domestic space. Rosters would be created for grocery shopping and cleaning; vegetables would be home-grown to avoid the perceived dangers of chemically treated food; and childcare would be shared between the women.

After only five months, however, several occupants felt that these aims had succumbed to the pressures of routine and reality. While practical problems around tidiness and dogs in the house were easily resolved, one resident, Jane, reflected that “all our ideals … fucked out completely.” Consistency was impeded by four women moving out and five moving in within this short timeframe. Perhaps more damagingly, there was a lack of communication around both personal relationships and shared goals: “some wanted it to be a house of political activity, some wanted the emphasis on communication of feelings [and] others wanted a place to live.”

This 1985 advertisement for a lesbian flatmate refers to the Wallace St flat, as can be inferred from the phone number. It is one of many, testifying to frequent changes in the residents of the house.

Wallace St may not have been a successful experiment in communal living, but the individual activities of its occupants ensured that it nevertheless became a social and political hub in Auckland’s lesbian community. Many women did lesbian-oriented work from the house, including several collective members of the publication Dyke News. Its large size was also ideal for meetings and workshops. These were sometimes socially oriented, such as Maureen Thompson’s astrology workshop with eight participants – “a good number in the space of my lounge.” Others were political, including a meeting about unemployment for which fourteen participants gathered in the same space. Yet despite its increasing publicity, Wallace St never lost its private character. Lesbians stopping by the house to buy a copy of Dyke News were not merely there on business, but always warmly invited to drop in for a cup of tea.

Blurring boundaries between private and public spaces

The public presence of the Wallace St house was perhaps its least unusual element. Indeed, although the patterns of queer housing changed from the 1950s to the mid-1980s, such publicity emerges as a strong and consistent theme. In the mid-twentieth century, privately hosted parties were the main avenue for queer socialising. Featuring music by the likes of the lesbian group Lavender Jane, these parties could be an introduction into queer culture. They could also be intensely competitive, as people attempted to impress their friends with sponge cakes and trifles. Either way, as one man, Billy Farnell, remembers, “gay people [went] to one another’s homes. That was the crux of the whole thing.” As queer communities gradually became more visible, these parties did not decline in significance but became accessible to more people. By 1984, open invitations to house parties were even placed in queer newspapers.

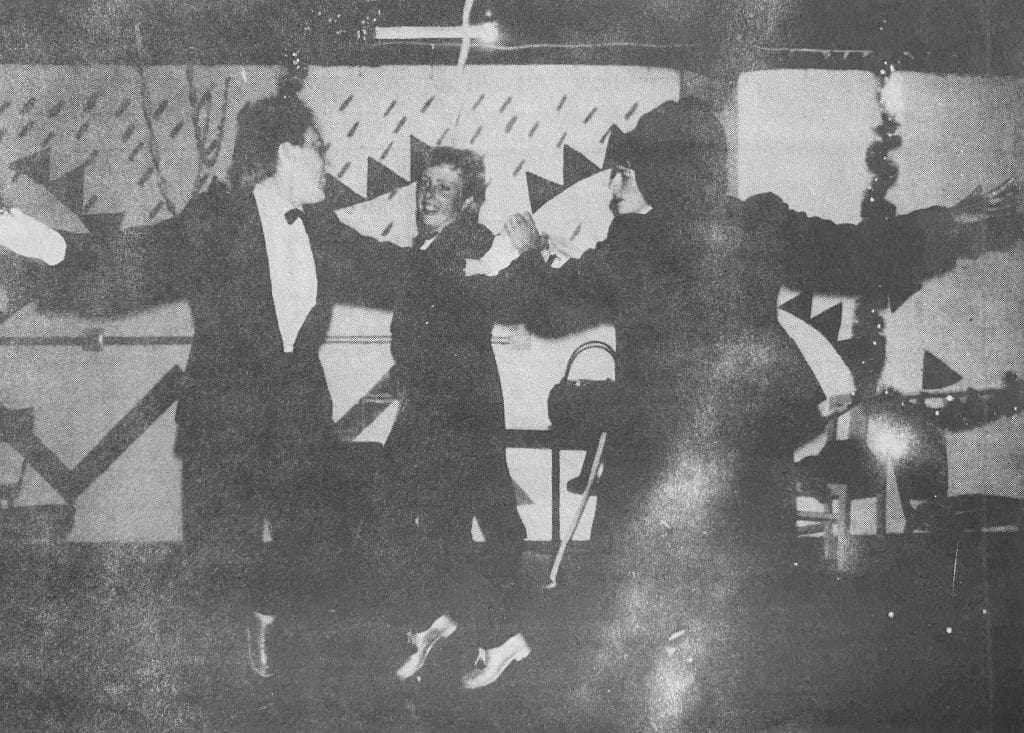

A lesbian household performing for ‘House Antics’ at the KG Club, December 1983.

The publicity of queer homes goes some way towards explaining why the household unit remained significant even as dedicated queer bars and clubs emerged in Auckland. Households often frequented these public spaces together, both informally and for organised events. The lesbian Karangahape Girls (KG) Club, for instance, featured flat performances at a ‘House Antics’ evening in December 1983. Wanganui Ave offered a synchronised dance routine, Paget St a musical drama, and the aforementioned Franklin Rd – whose residents planned the event – sang together. Houses thus shaped the lives of queer Aucklanders in more than a spatial sense, also fostering a sense of collective identity. Public spaces like the KG Club, however, were even more prominent in queer communities’ experiences of the city. The development of these spaces, which occurred alongside that of queer homes, is the focus of my next article.