Part Four

“Out of the Closets and into the Streets”: Conceptualising Auckland as a Queer Space

by Frederike Voit*

My preceding three articles have explored the private and public spaces which Auckland’s queer communities created from the mid to late-twentieth century. Yet the fact remains that it was impossible for queer people to live solely in queer spaces. Not only did familial relationships, education, and employment require significant time to be spent in non-queer surroundings but, as I have previously noted, queer spaces themselves were embedded within the landscape of mainstream Auckland. This article traces the evolution of this relationship between queer people and the city, approaching Auckland itself as a space that was occupied and shaped by queer communities.

This is not to say that queer people were always welcome in mainstream areas of the city. Throughout the period from the 1950s to the mid-1980s, a significant proportion of Aucklanders saw and treated queer communities with contempt. This attitude followed queer people throughout their lives, from homophobic slurs at school to the constant risk of losing employment as adults. “When you walk down the street, you realise there’s a barrier between you and the outside world,” as one gay man, Paul, described his life in Auckland. His experience certainly reflected the majority, and it is not my intention to understate the discrimination which these people faced. Yet the fact that such discrimination occurred at all, and that it was reported on – sympathetically and otherwise – in the city’s newspapers, is a testament to the open existence of many queer people in mainstream Auckland. Although they were silenced and suppressed, queer communities consistently attempted to carve out space for themselves in the city.

In a few cases, even as early as the 1950s and 1960s, they did succeed. Some queer people found accepting friends, while others sought employment with businesses that were informally known to welcome them. Such connections also helped to protect queer people when they inevitably encountered discrimination or legal trouble. This was the case when Trevor Rupe, a drag queen better known as Carmen, was taken to court for ‘behaving offensively’ in 1966. The residents who lived at Rupe’s boarding house told the judge that “we don’t care what he is … he’s a very kind person.” Rupe was found not guilty in a landmark verdict. Several years later, such acceptance was becoming increasingly common. It even became possible for the lesbian Operations Manager Bobbie to bring her girlfriend to a company Christmas party, where everyone “got along very well.” Personal relationships between queer and non-queer Aucklanders thus occasionally transcended societal intolerance, enabling some queer people to live relatively openly in the city. By the 1970s, such relationships were no longer the only way to achieve this liberation.

The personal becomes political

1972 was a dramatic year for queer people in mainstream New Zealand, and Auckland took centre stage. In March, the country’s Gay Liberation movement unexpectedly began at the University of Auckland with a speech by lesbian activist Ngahuia Te Awekotuku (then Ngahuia Volkerling), who had been denied a visa to study in the United States for the reason of ‘sexual deviance.’ Public knowledge of her situation catalysed the formation of Auckland’s Gay Liberation Front (GLF) which, weeks later, organised New Zealand’s first gay ‘happening’ in Albert Park. This protest was a broad statement against the discrimination which queer people encountered in mainstream Auckland. More specifically, it also demanded a response to a letter which had been sent to the city’s mayor, Dove-Myer Robinson, about such discrimination. While the Gay Liberation movement failed to achieve immediate results – not least because Robinson refused to meet with the GLF – it hereby set the tone for queer political activism in Auckland. As one participant jubilantly announced, “we’re coming out – out of the closets and into the streets!”

Left: Ngahuia Te Awekotuku addresses protestors at a Gay Liberation march.

Right: A scene from the gay happening in April 1972, taking place in front of the statue of Queen Victoria in Albert Park.

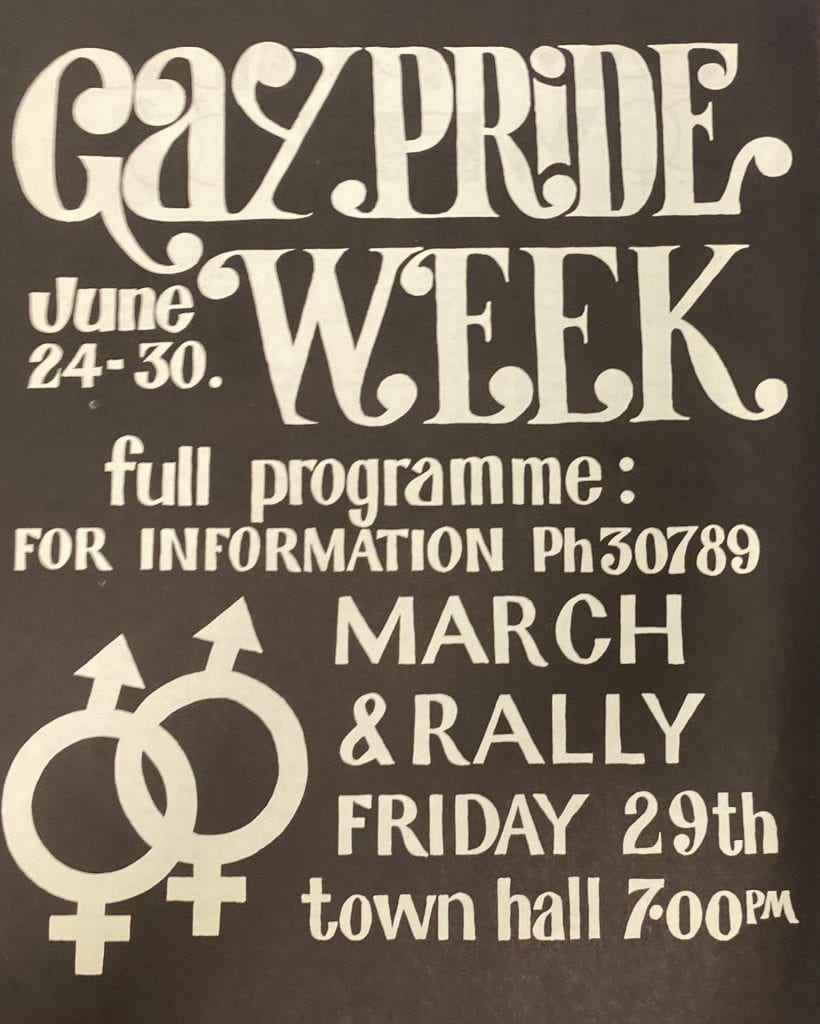

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, the closely linked Gay Liberation and Homosexual Law Reform movements continued to occupy the streets of Auckland. Marches and rallies ebbed and flowed, largely coinciding with the various campaigns to change the nation’s laws around homosexuality. Earlier legislative efforts, notably in 1968, had failed to gain widespread traction. By 1973, however, the Gay Liberation movement had gained enough members to organise Auckland’s first Gay Pride Week. The following year, queer people again took to the streets in support of the Crimes Amendment Bill, which would have legalised sex between men aged over twenty-one. And in 1985, an even more visible campaign began around the Homosexual Law Reform Bill. Yet marches were not the only way that queer Aucklanders engaged with political activism. Many simply did what they always had, trusting and gradually confiding in their non-queer friends and co-workers. This was no longer merely a personal decision, but had become “a tactic in … homosexual law reform.” This shift, more than anything, demonstrates how the 1970s and 1980s politicised queer people’s lives in mainstream Auckland.

A poster for Auckland’s first Gay Pride Week. This was held in June 1973 to coincide with the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, which began Gay Liberation in the United States.

Bridging private, public, and mainstream spaces through political activism

The rise of political activism is a well-researched aspect of Auckland’s queer history. Reflecting the spatial focus of my project, however, I approach this topic from a slightly different angle. It has become clear throughout my previous three articles that queer private, public, and mainstream spaces developed in parallel. Queer homes grew in popularity and dedicated queer venues began to emerge during the 1970s, the same decade in which Gay Liberation changed queer people’s lives on the streets of Auckland. As these parallel developments imply, the city’s various types of queer spaces were far from separate. In fact, as I explore in the remaining section of this article, political activism in the 1970s and 1980s was the point of convergence between queer public, private, and mainstream spaces.

On a practical level, queer homes and establishments were involved in the campaigns for Gay Liberation and Homosexual Law Reform. The GLF’s early protests in mainstream Auckland were organised from private houses in Remuera and Parnell until the growing size of the organisation made this impracticable. After this stage, queer public venues became involved. Queer people seeking to express support for the Homosexual Law Reform Bill in 1985, for example, were referred to the lesbian Snapdragon bookshop to find a list of Members of Parliament to lobby. In the same year, Snapdragon was also instrumental in the organisation of a Lesbian Visibility Week. This culminated in a rally at the Town Hall, for which the KG Club held both preparatory workshops and an afterparty.

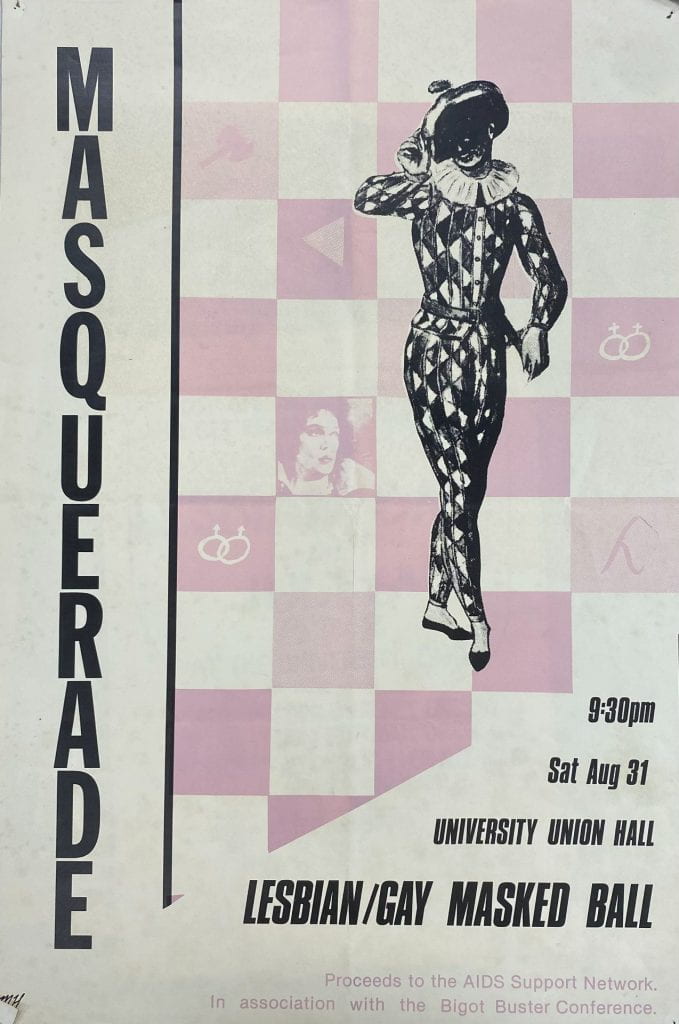

While these connections between queer homes, queer venues, and mainstream spaces were forged through political campaigns, they became truly vital during the fight against HIV/AIDS. This new disease, first discovered in New Zealand in 1984, was “far more than a bedroom issue.” Queer establishments provided information workshops, while fundraisers for the New Zealand AIDS Foundation were held at numerous venues including the lesbian-owned Alexandra Tavern. Such publicity was not limited to queer spaces. Indeed, queer communities felt that non-queer Aucklanders’ lack of knowledge on HIV/AIDS “intensifies feelings of sexual oppression [and thus] the issue should be out in the open.” This resolution gave rise to a plethora of HIV/AIDS-related events in mainstream spaces, such as a ball at the University Union Hall to raise awareness and funds for the AIDS Support Network. HIV/AIDS became a second issue which permeated queer homes, venues, and mainstream spaces equally, not only as an infectious virus but as a unifying social cause.

A poster for the Lesbian/Gay ball held at the University Union Hall in 1985, specifying that proceeds would go towards the AIDS Support Network.

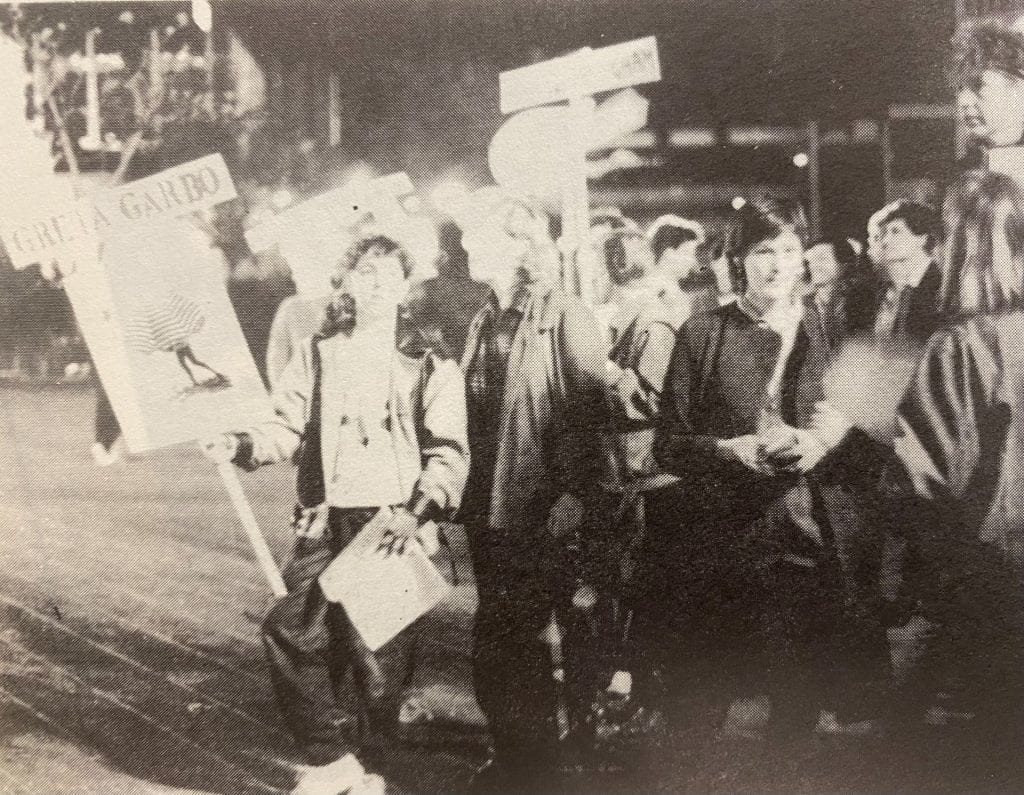

Beyond practical collaborations, these spaces also converged in a less tangible but ultimately more significant way. Gay Liberation marches and rallies in the 1980s were no longer solely driven by political anger, but incorporated and mainstreamed the celebratory culture that had underpinned queer house parties since the 1950s and become institutionalised in queer bars and clubs during the 1970s. The street theatre performances, protest music, and occasionally costumed demonstrations of this era all took their inspiration from these existing spaces. The Gay Liberation movement had, in its early years, attempted to channel such festivities into separate social outlets. Concerts followed workshops, while an exhibition entitled ‘Gay Culture/Gay Art’ was held during the otherwise exclusively political 1974 Pride Week. Once released from the confines of queer homes and venues, however, the spirit of celebration and social connection proved to be a seamless complement to political activism. As Bernie Sheehan, a self-proclaimed protest addict, reflected, “[marches are] such a social occasion, good for … catching up on gossip in between kicking policemen in the shins and chatting between the chanting.”

Protestors gather at the Lesbian/Gay Rights March in September 1985, which was described as having a “lovely, carnival atmosphere.”

The incorporation of this celebratory culture into Gay Liberation events was controversial. One march in Aotea Square in September 1985 drew particular ire, with protestors deploring that “great political speeches” had taken second place to dancing and balloons. Yet the same march also revealed how this festive atmosphere, familiar from queer homes and venues, helped to engage queer communities with political activism. Several participants, who were anxious about entering mainstream spaces and encountering the conservative backlash against Gay Liberation, described how it made them feel “safe” or even “elated.” The merging of private, public, and mainstream spaces in this way thus arguably contributed to the Gay Liberation movement’s most significant achievement, the passing of the Homosexual Law Reform Act in July 1986.

Auckland’s queer spaces after Homosexual Law Reform

The campaign for Homosexual Law Reform had brought the culture of queer spaces into mainstream Auckland. Now, it seemed that the Homosexual Law Reform Act would eliminate the need for these spaces altogether. The Act had raised hopes for “a society in which there will not be two distinct groups of homosexuals and heterosexuals.” Queer people would be welcome in mainstream spaces, rather than relegated to separate queer homes and venues. Perhaps reflecting these hopes, many of the venues which have featured throughout this project began to decline from the mid-1980s. The KG Club, after failing to replace its last premises, closed in 1985. The Backstage Club also closed in the 1990s. And the Staircase Club, which survived, gradually transitioned towards a mixed queer and non-queer crowd.

Yet Homosexual Law Reform did not make queer spaces redundant, because it also did not end the intolerance shown towards queer communities in mainstream areas of Auckland. Initial hopes of equality were tempered when the section of the Bill addressing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation had failed to pass into law. “External pressures on gay people are likely to get worse [if] the human rights section of the law reform fails,” as Gayspace News predicted, “and there will be a greater than ever necessity to have community welfare needs taken care of.” Another generation of queer spaces was required to replace the old. Queer flats continued to be established and a surge of new queer nightclubs emerged in the 1990s, from the mixed-gender Midnight Club to the lesbian Footsteps and Lassoo clubs.

People gathered in Aotea Square during Auckland’s annual Pride Festival, which also contains echoes of twentieth-century queer spaces. Photo by Friederike Voit, February 2023.

Anyone who is familiar with Auckland today will know that these spaces from the 1990s no longer exist and that they have been replaced, once again, with newer and fewer alternatives. Yet this does not mean that queer communities or queer culture have disappeared from the city. To the contrary, they are more visible than ever, both in large-scale events such as the annual Auckland Pride Festival and in everyday acts of inclusion. This, I would argue, is the ultimate legacy of the private homes, public venues, and mainstream areas which were occupied by queer people from the 1950s to the mid-1980s. These spaces fostered the culture of today’s queer communities and, when they united around the Gay Liberation and Homosexual Law Reform campaigns, they introduced this culture to the streets of Auckland. Auckland’s queer spaces still survive in the twenty-first century, in the form of Auckland as a queer space.