Part Two

“This was Paradise”: The Rise of Queer Public Spaces in Central Auckland

by Frederike Voit*

“This was Paradise”: The Rise of Queer Public Spaces in Central Auckland

Auckland’s queer communities never remained hidden in private homes. Throughout the period from the 1950s to the mid-1980s, they also occupied a number of public areas and venues in the city. As queer homes consolidated into a large network of flats, queer public spaces were evolving in parallel, transforming from informal gathering-points into dedicated queer establishments. This shift had been signalled early in the twentieth century, when gay men had first ventured en masse into spaces such as Blake’s Inn on Vulcan Lane and the area outside the Ferry Building. Yet it was in the mid-twentieth century that such meeting places began to multiply, laying the foundation for a landscape of queer public spaces in the central city.

The 1950s saw numerous inner-city establishments gain reputations as queer spaces. Coffee bars like the Ca D’Oro on Customs St were known to cater to an alternative clientele, a fact which also attracted queer patrons. The Ca D’Oro, like the Lilypond at the nearby Great Northern Hotel, also had the advantage of being close to the wharf. As those who lingered around the Ferry Building in earlier decades had already discovered, this area was frequented by merchant sailors who often spent their time in Auckland engaged in social or sexual encounters with the city’s gay men. These sailors not only influenced the location of queer public spaces but also shaped their character. Les Mack, for example, recalls the excitement when a transistor radio from one of the ships enabled wireless music to be played at the Lilypond for the first time. Unfortunately, such excitement often reached an early end. Many public spaces were bound by six o’clock closing restrictions, a legacy of World War I efforts to curb New Zealanders’ alcohol consumption. As the evening grew later, queer people thus either concentrated in the few venues which remained open – such as the Ca D’Oro, which spent its legally extended hours illegally serving alcohol in coffee cups – or departed for private house parties.

The Great Northern Hotel, where the Lilypond, a popular gay meeting place, was located. Photo by N. M. Dubois, 1970s.

The emergence of dedicated gay and lesbian establishments

With new alcohol licensing laws and the advent of ten o’clock closing in 1967, a major limitation of public spaces disappeared. Dedicated queer establishments rapidly replaced the earlier system of informal congregation. These spaces reached their target clientele without much effort, as proprietors were often well-known queer Aucklanders. OUT! Magazine publisher Tony Katavich, for instance, was certainly aided by his reputation when he opened Alfie’s nightclub in 1980. More systematically, public spaces also attracted queer communities by advertising in Auckland’s growing number of queer publications and by restricting membership, as the gay Aquarius Society did, to one gender. For the first time, the city had a range of exclusively queer bars and clubs: “this was paradise.”

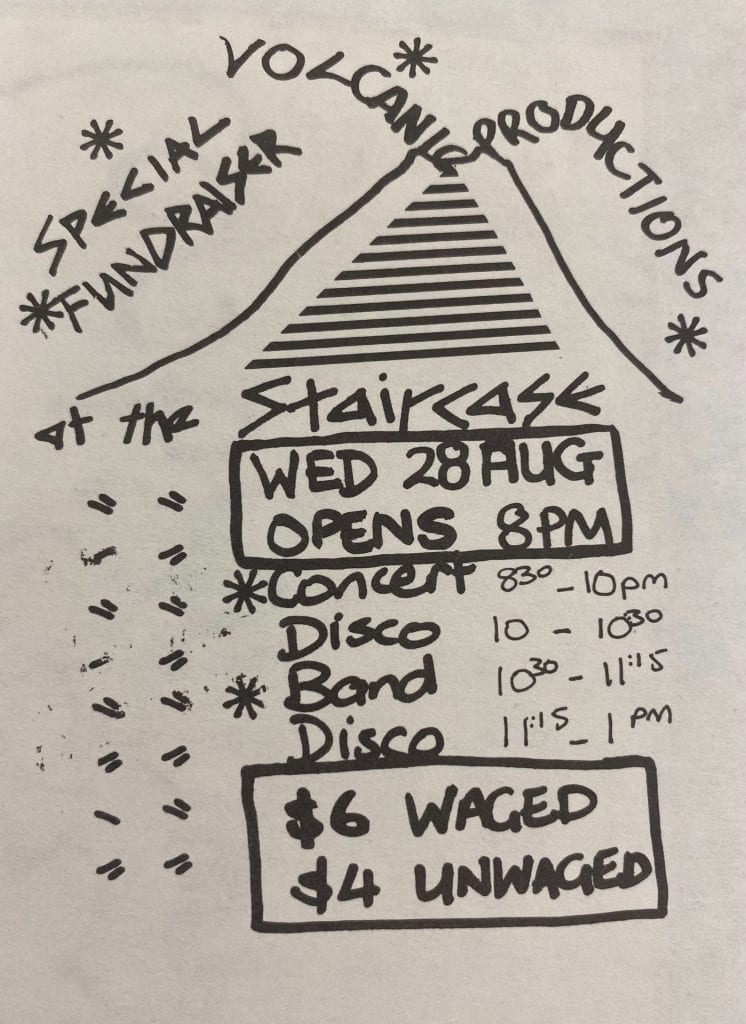

Yet Alfie’s and the Aquarius were far more than places to dance. Most gay establishments were businesses and also employed gay people. Russell Green worked as a dishwasher at the Mae West Bar in the Empire Hotel, for instance, while his partner Billy Farnell was a pianist at venues including the Staircase Club. Additionally, queer entertainers like the band Volcanic Productions found an audience at these spaces. This group held a fundraiser at a Staircase women’s night in August 1985, selecting the venue not only for its acoustic advantages but because their predominantly lesbian audience would “feel comfortable” there. Despite the Staircase taking all of the bar profit and forty percent of door entries, Volcanic Productions successfully raised $340 towards their first tape. Proprietors, guests, employees, and entertainers alike thus all found what they needed in Auckland’s gay spaces.

Advertisement for the Volcanic Productions fundraiser at the Staircase, 1985.

The lesbian community were also well-served by their most significant venue, the KG Club, which was established near-contemporaneously with gay clubs in the early 1970s. Unlike these, however, the KG Club was a community project rather than a business. A group of women converted a former hairdresser’s salon on Karangahape Rd, a run-down place with persistent plumbing issues, into a functional venue. Their aim to establish a community space was reflected in the KG Club’s eventual registration as an incorporated society, which ensured that it would not generate profit for members of the governing committee. Even beyond the requirements of this legal framework, all work at the KG Club was voluntary – with the singularly feminist exception that two cleaners, Joanna and Janet, were paid. In this way, the space not only embodied but actively strengthened the sense of community among Auckland lesbians. Disagreements about its management were always tempered by the sympathetic sentiment that, as one woman, Annie, expressed, “lots of us in the community have done our time on [the KG committee].”

As the main community centre for Auckland lesbians, the KG Club also had a wider range of functions than individual gay pubs and clubs. It even celebrated a lesbian wedding shortly after its establishment. On this day, the club opened early on a Saturday afternoon, a ceremony was held, and the entertainments, which lasted into the next morning, included “light opera” and an Elvis impersonator. “We did it because that’s the way we felt,” and the KG Club made it possible. While weddings remained a rarity, the club later expanded its services in a more official sense as the Inner City Women’s Recreation Centre. It became the training location for a softball team, offered weight training classes, and hosted organisations like the Lesbian Action Group. The KG Club thus supported its community just as gay spaces did, though in distinctly different ways.

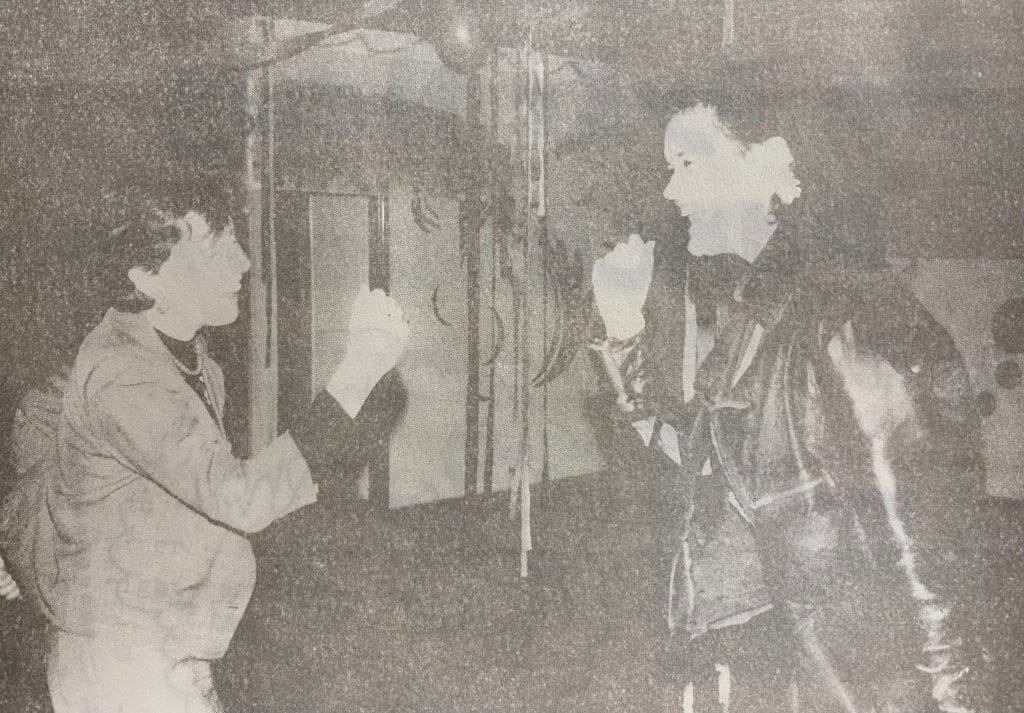

Women dancing at the KG Club in 1983.

Connection and co-operation among queer public spaces

While the distinctions between gay and lesbian venues were significant, and have been implicitly emphasised by historians discussing these spaces separately, this is not the full story. Auckland’s queer spaces were also interconnected and supported one another. When the KG Club was initially established, for instance, assistance in finding and financing premises was offered by the gay Aquarius Society. This debt was paid forward when the club later hired its premises out to other queer organisations – occasionally even without a fee. In a less altruistic example, after the lesbian-frequented Empire Tavern changed ownership in 1982, Kevin Smith from the Mae West Bar invited lesbians to join the gay men there. The offer was accepted, with around thirty women arriving on the first night.

This last episode speaks to the role of queer people themselves in creating connections between public spaces. Patronage of these spaces often overlapped, with gay and lesbian venues holding open nights for women and men respectively. This occurred in the early years of the KG Club, where men were permitted entry one night per week. While the KG Club’s open night policy was later reversed, other venues became increasingly mixed-gender over time. The Staircase held its first women’s night in June 1985. Similarly, the Backstage Club, which opened in 1976, was permanently open to Auckland’s whole queer community. Rather than differentiating itself as a gay club, it was marketed towards the theatre profession with monochrome décor, wallpaper featuring silent movie stars, and spotlit lighting. Yet the overlap in the clientele of queer spaces, somewhat surprisingly, did not translate into a clear spirit of competition. Backstage’s manager Lew Pryme even suggested that a greater number of venues would benefit all, “with the other clubs gaining new members who weren’t satisfied with [one] but had come out through it.”

While queer spaces were thus connected to each other, they were also integrated into the wider landscape of Auckland. Safe movement between public venues and private homes was a particular concern. Clubs created maps that pointed the way to the nearest taxi station, as well as encouraging people to walk home together or even organising transport when required. In addition to queer people finding their way out of public spaces, ‘square’ and later ‘straight’ society found its way in. Drag performances were especially popular with this audience, who frequently patronised queer establishments such as Mojo’s on Queen St. This interaction of queer and non-queer worlds, while it could be mutually enriching, was not without its difficulties.

The challenges facing queer spaces in a non-queer city

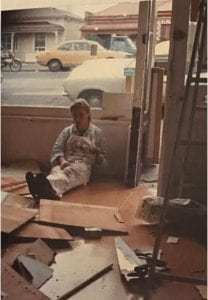

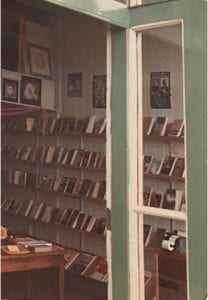

Simply being a queer venue in the 1970s and 1980s was challenging. The lesbian Snapdragon collective recognised the potential for discrimination even before opening their bookshop on Jervois Rd, initially not disclosing their sexuality out of fear that they would not be registered as an incorporated society. While their registration was approved without issue, the existence of a lesbian bookshop was certainly not met with universal support. Snapdragon was reprimanded by the Human Rights Commission after a male customer complained about certain books only being sold to women. In this case, a perfunctory response from the collective sufficed: the ‘women only’ sign was taken down, but the policy remained unchanged.

During and after the renovation of the Snapdragon Women’s Bookshop, which was carried out by members of the collective.

More serious consequences resulted from encounters with the police. Liquor licensing laws remained convoluted, with the result that raids on bars and clubs were not uncommon. They were also not unique to queer spaces, although raids on queer venues appear to have been more likely to escalate. This was sometimes, as during a 1976 raid on Backstage, the result of police making derogatory remarks about queer communities. On other occasions, queer people simply felt threatened by the police presence – especially as police questioning created a record of them having been in a queer space – and reacted aggressively. In either case, raids had the potential to cause significant damage. Backstage’s Lew Pryme was convicted on five charges of unauthorised liquor sales and fined $75, but succeeded in protecting his club. The KG Club was not so fortunate when, two years later, its Beach Rd premises were permanently closed after a similar raid.

This discrepancy likely reflects the fact that the KG Club, like many queer spaces, also faced significant financial issues. Its predominantly working-class committee did not bring their own capital to the club, and supported their similarly working-class customers by charging lower fees for the ‘unwaged’. On several occasions, such policies combined with high inner-city rents brought the KG Club to the brink of liquidation. An interim committee, established to avert this possibility in 1979, laid out the dire situation: the club was $3800 in debt while its weekly profit was a mere $70. Good relationships with creditors meant that the debt could be repaid slowly, yet this option was not available to all. The Snapdragon collective, when suffering financial difficulties of their own, were obliged to go through the arduous process of securing government support. One funding application was initially declined on the grounds that lesbians were not a “disadvantaged group.” And while the bookshop later did pay two employees through a different government scheme, this, too, only sufficed to cover limited opening hours.

Transforming challenges into opportunities

At times, the overlapping struggles against discrimination, financial strain, and outdated liquor laws and government policies became insurmountable. The KG Club had no choice but to relocate at least three times between 1971 and 1985. Other queer public spaces became similarly transient, with the Aquarius Society moving to Victoria St West in 1975. While these shifts naturally sparked uncertainty, they were also opportunities to re-evaluate the role of a venue in Auckland’s queer landscape. With the Aquarius’ change of premises, for instance, the club also expanded its range of services. Daytime opening hours were introduced, as well as amenities including a coffee lounge, pool table and colour television. In this sense, transience was not a threat to existence. Rather, it enabled queer spaces to evolve with the changing needs of Auckland’s queer communities, becoming more than a physical location.

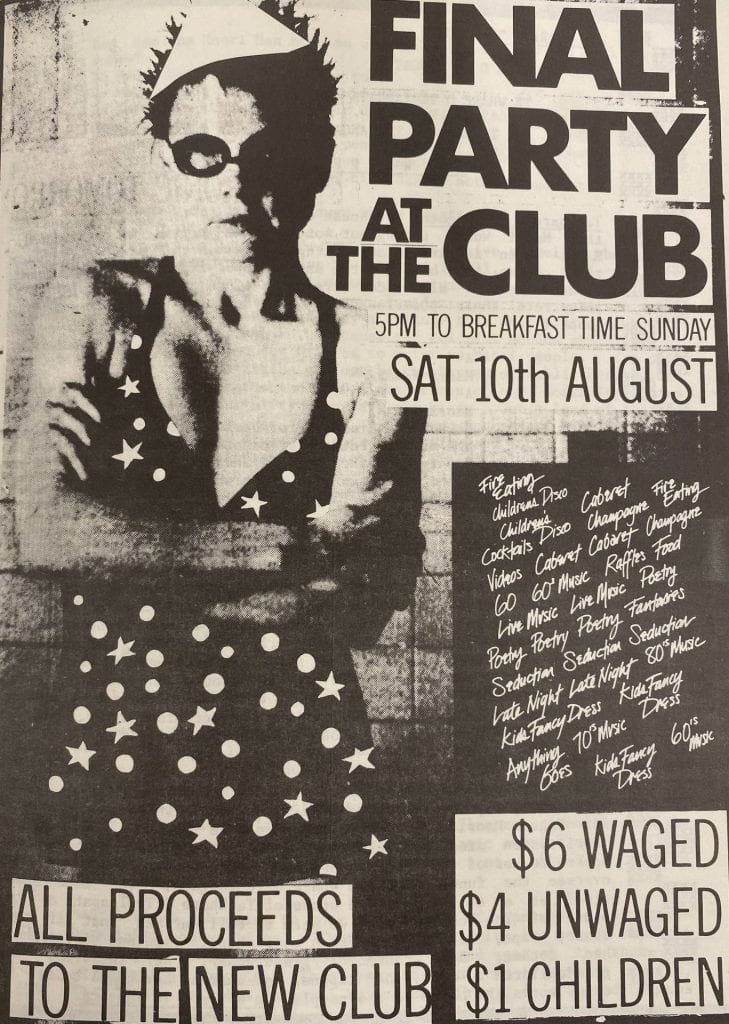

A 1985 advertisement for a KG Club party, with proceeds going towards new premises.

Some queer organisations even endeavoured to be transient from the outset. By occupying non-queer spaces at specific times, such organisations side-stepped the financial and logistical challenges of a permanent venue. This strategy was successfully adopted, for example, by the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) and its congregation of “gay people and friends.” With only twenty-five regular attendees when the Rev. Peter Alexander-Smith was appointed as its first pastor in 1977, establishing a new church was not an option for the MCC. Worship was instead conducted at St Matthew-in-the-City every Sunday evening from eight o’clock. This enabled the organisation, and others like it, to join the ever-growing network of queer public spaces in the heart of Auckland. Yet there was a hidden cost. As these spaces continued to increase in number, they were leaving some queer people behind. My next article takes a step back, retelling the story of queer public spaces from these people’s perspective.