Part Three

Wide Plains and Padded Cells: The Anatomy of an Asylum

by Sasha Finer*

Three things, at least, have to be looked to in providing for the insane. The first is, that they should be placed under sufficient restraint to prevent their doing harm to themselves or to others; secondly, that, in cases where reason is not irrecoverably gone, the patients shall be surrounded with facilities for aiding in their speedy restoration into society; and thirdly, that those who have to remain for a considerable time in the Asylum, and those who are deemed to be hopelessly lunatic, shall have the wretchedness of their lot ameliorated by all possible means.

Daily Southern Cross, 25 October 1866

Cultural attitudes towards mental illness in 19th century New Zealand tended after the Victorian model, which was perhaps evidenced in the eager adoption of the lunatic asylum as a means of dealing with the insane. Contemporary medical thought was that madness was an affliction with “its centre in the organs, and its seat in the mind”, which necessitated a similarly dual treatment – either “moral or physical remedies”. This concept of duality in madness, while probably not causally related, was certainly reflected in the cultural attitudes of dealing with the mentally ill at the time. It had previously been general practice to imprison those whose minds and behaviours deviated from the norm, but this kind of treatment weighed uneasy on the mind of what was an overwhelmingly Christian society. Morality, it had become more and more evident, must also be considered in the treatment of those of unsound mind.

The question raised was how to go about balancing a more moral approach with continuing to separate and confine those whose presence in ‘normal’ society was too uncomfortable. The answer, an attitude which would characterise mental health treatment for decades after, was that the insane should be separated and confined for the safety of others and of themselves. It was fine to continue imprisoning the mentally ill, as long as that imprisonment was suitably moral – replace the gaol cell with an asylum dormitory and balance would be established. The Victorian lunatic asylum was consequently a purpose-built ‘moral structure’ – a building spatially concerned with the contradictory efforts of treating morally, as well as separating and confining, the patients it housed. The new Auckland Lunatic Asylum was a building that, like its Victorian predecessors, was built for moral treatment, but also to separate and confine. This dichotomous expression of cultural attitude was physically exhibited in the Auckland Asylum in two key areas: the site chosen for the asylum, and the structural features of the building itself.

One of the most crucial decisions involved in the construction of the asylum was where to build it. While on paper the decision to build the asylum at the Whau seemed relatively straightforward, in reality it was the product of a tangled web of many factors including practical considerations and cultural attitudes. The Colonist’s list of criteria regarding the ideal site of an asylum demonstrates the range of these. It is relatively simple to see why practical considerations, such as the water supply and drainage of the soil, were included. It is less obvious why other criteria were added to the list: that the asylum should be built on land “undulating in its nature” is an oddly specific demand, and doesn’t seem like it should be considered as necessary a criteria as distance from “any nuisance, such as steam engines, shafts of mines, noisy trades, or offensive manufactures”. But many of these less evidently practical criteria are a product of cultural attitudes and ideas at the time regarding lunatic asylums and the lunatics themselves.

Some of the contradictions in these criteria reflect the contradictions in the attitudes themselves. The asylum should be “as central as possible to the mass of population in the country or district for which it is to be erected, and should be convenient with respect to its easy access by public conveyance, in order to facilitate the visits of friends and the supply of stores”. Yet it should also be separate from any of the noise and industry of many populated areas, and it should not be “surrounded, or overlooked, or intersected, by public roads or footpaths”. Moral treatment was to be provided in allowing visitors to access patients without difficulty and in ensuring supply of stores, while separation and confinement was to be provided in keeping the patients closed in and distanced from the public and their thoroughfares. The location of the asylum must be central but not too central; the patients must be accessible to the public, but the public must not be accessible to the patients.

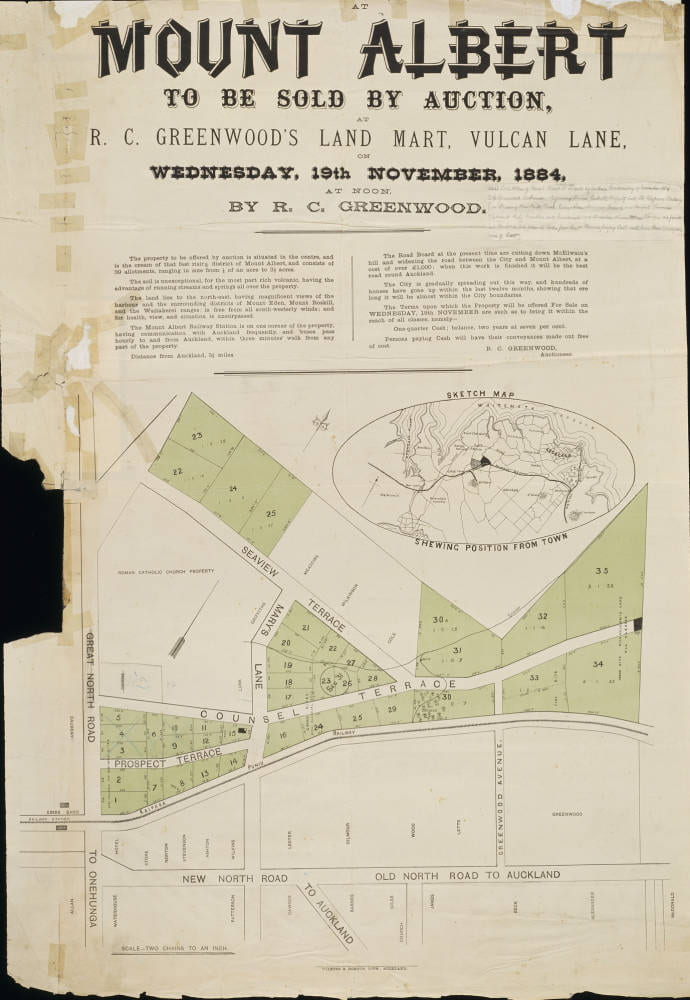

A map showing sections up for auction in Mt Albert, 1884. This is an area a little southeast of the asylum and its grounds, which are noted in very small font on the ‘sketch map’ provided. Many similar auction maps show various sections for sale surrounding the asylum during the 1880s; it is easy to see how, prior to these allotments being sold off, the asylum would have been relatively isolated from residential areas. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, Map 4497-5.

The site and its patients were indeed easily accessible by the public, as evidenced by the account of a visit to the lunatic asylum by a man writing to the Daily Southern Cross. The walk to the asylum is noted as a little over three miles from the city “by the Great Northern Road”, and the asylum itself is described as standing largely alone “in a wide plain, its bright red contrasting with the sombre hue of the surrounding fern: the sparkling waters of the Waitemata on the one hand… with a background of pine-clad hills away beyond the head of the Waitemata harbour”. The man (a member of the public who arrived unannounced, with no connection to any individual patient) described being taken on a full tour of the facility by a warden. This included entering the dayroom and various other rooms to view and interact with the patients, whom he described in great detail – the overwhelming effect was of a visit to the zoo. Clearly the public were allowed to come and go as they pleased; the same certainly could not be said for the patients.

The restriction of the patients was demonstrated in not just the site choice, but in the structure of the building itself. While comfort and design were considered to a degree, these factors occupied only one end of the ever-present dichotomy between moral treatment and separation and confinement. The floors were outwardly of hardwood and tile, but in areas “where extra security is deemed necessary” they were constructed from a dual layer of concrete and bricks. The doors which provided patients access to the world outside the asylum were made of iron; the windows which let in light and allowed views of the grounds were “sashed and framed with iron of slender looking proportions, but of great strength if tested”., The dormitories, where the patients slept, had “very much the aspect of prison cells”. But nowhere in the building itself were the contradictive cultural attitudes at the time made more apparent than in what the New Zealander described as the “dread ‘padded cell’”.

One of the many dormitory windows of the asylum, still a part of the building today. Although the iron sashes are no more, this narrow window (about a metre high, and no more than 35cm across) demonstrates the cell-like conditions of the patients’ rooms. Photograph taken by author, February 2023.

If any physical feature of the Victorian lunatic asylum could be said to best represent the contradictory attitudes to mental illness at the time, it was the padded cell. The phrase itself is a contradiction, nearly oxymoronic: ‘padded’ brings to mind a comfortable setting, whilst ‘cell’ does nothing of the sort. In keeping with the cultural attitudes towards lunacy and its treatment, the function of the padded cell perfectly exhibits the desire to separate and confine the insane so that they cannot harm others nor themselves. The room is a cell; the lunatic can do no harm to others. The walls are padded; the lunatic can do no harm to themselves. As an object of morbid fascination, the padded room has persisted in our cultural memory across centuries, and along with the straitjacket it is probably one of the first things that springs to any person’s mind when thinking of the Victorian lunatic asylum as an institution.

The padded cell was no less an object of morbid fascination to those who visited the Auckland Lunatic Asylum. The asylum contained at least two padded cells, one of which was described extensively and with avid fascination by a writer for the New Zealander:

“Having seen these rooms, we were about to pass one outwardly similar when our attention was arrested by hearing that it was the “padded room.” We instantly expressed a wish to see it, and we were at once gratified. The heavy door was thrown open, and we looked in. About nine feet long by seven wide, with heavy leathern paddings on every side, to the height of some seven feet; the door was also padded, as was likewise the door, the floor very thickly. The paddings were very soft and thick, and however much the poor unfortunate might rave and dash himself about, it would be difficult, we should imagine, for him to injure himself in this “padded room”… Having examined the place with considerable curiosity, and, we must confess it, not without a shudder, we quitted that part of the corridor, with a sincere pity for any human being whose madness should become so raving as to necessitate his being confined in the padded room.”

The man who wrote to the Daily Southern Cross also noticed the padded cell, despite only glimpsing it in passing, noting that the “walls and door all heavily padded showed the paroxysms of frenzy from which its poor inmate was protected”. He noted also that the patient confined within the cell was wearing a straitjacket, as was another patient – although he was perhaps unfamiliar with the name of the garment, describing only that the patient stood with “arms folded on his breast and his sleeves covering his hands… fastened behind his shoulders”.

Excerpt from “Wanderings Around Auckland: The Lunatic Asylum”, Daily Southern Cross, 1 December 1869.

One of the many dormitory windows of the asylum, still a part of the building today. Although the iron sashes are no more, this narrow window (about a metre high, and no more than 35cm across) demonstrates the cell-like conditions of the patients’ rooms. Photograph taken by author, February 2023.

There is no doubt that life in the new asylum was a cheerier prospect than imprisonment in the city gaol or the dismal hospital asylum. Nevertheless, the asylum’s veneer of moral respectability only masked what was still at its heart the same attitude of separation and confinement that justified locking up lunatics in gaol cells, and the asylum itself can’t have felt like anything but a slightly more upscale prison. Control of the insane did not stop at separation and confinement, however; the patients lived a regimented life under the watchful gaze of the attendants, as my next essay will touch on.