Part Three

1940s Fashion in Auckland, New Zealand

by Caitlin Kilpatrick*

“A bewildered follower of fashion might well ask, “What on earth have they in store for us next?”

This question, posed by the Mirror in 1947, weighed on the mind of Auckland women during the 1940s. A decade that would bring wartime scarcity and post-war prosperity, the 1940s were a time of uncertainty. This did not stop rapid changes in fashion and changing clothing throughout the decade. With George Courts, Rendells, Milne and Choyce, Farmers’ Trading Company, John Court and Smith and Caughey still lining the streets of Auckland, women had numerous opportunities to stay up-to-date with all of the latest fashion trends.

Clothing Rationing

From 1939 to 1945, World War II was a primary concern. This led to disruptions across all aspects of life – including fashion.

Clothing and textile rationing was a measure introduced across many countries. Rationing was introduced for a range of reasons, one of which was to “restrict consumption and put a brake on inflation,” as encouraging saving in that area would hopefully benefit the overall economy. There was also a desire to reduce the pressure on importation, as import and export restrictions during the war had led to shortages of common clothing materials such as linen and cotton. Finally, these rations allowed labour otherwise tied up in clothing production to be redirected towards war industries and overall benefit the war effort instead.

Those on the home front in New Zealand began to feel impacts in May 1942, when clothing and fabric rations were introduced. Adults were allotted 26 coupons per half-year, which could be spent on clothing and textile items. This number was chosen so that most classes of people could manage reasonably comfortably. These coupons were first introduced with six-month expiry dates, which invariably led to panic-buying near the end of the timeframe. These expiry dates were removed in 1943, ensuring that people were better prioritising their spending in order for the coupons to serve their purpose.

Despite the understanding of the necessity of rationing, these coupons were not entirely uncontroversial. While people were grateful that clothing was rationed before food, as “the life of clothes can be prolonged beyond their normal span” more easily than food could be, material rations seriously impacted housewives. The New Zealand Herald argued that the rationing measures added new complications, especially for housewives, and discussed the urgent need for regulations on the coupons to protect “husbands’ and fathers’ ration books from raids by wives and daughters.” Undeniably, women who were more concerned with fashion were impacted most by clothing rationing, as they were no longer able to stay in trend, but these clothing rations had wide-spanning effects across all aspects of the fashion system.

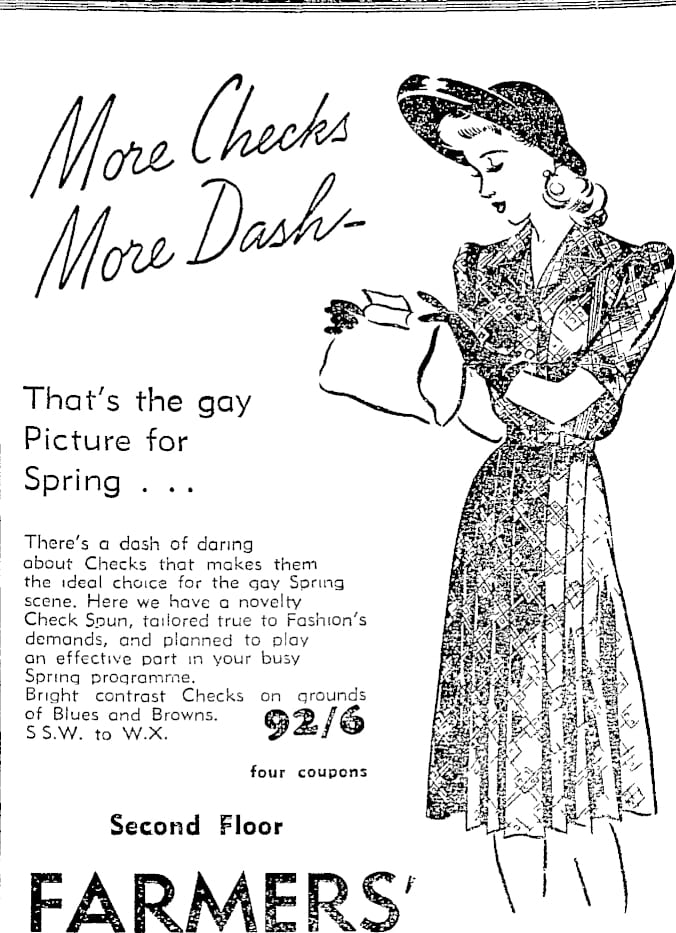

From the early 1940s to mid 1940s, there was less material available to make clothing, as well as fewer customers in the market purchasing clothing. This shaped the fashion industry of Auckland, leading to changes in their operations. To reflect these changes, advertisements for clothing and catalogues began to display both money values and coupons values for their clothes, allowing women to plan out the use of their coupons.

Image 1: Advertisement for Farmers’ feature the price in money (92 pounds, 6 shillings) and in coupons (four coupons). (Image by Farmers’ Trading Company for Auckland Star, 26 August 1943.)

Value in Clothing

For the fashion-minded woman, the restrictive nature of clothing rationing certainly impaired her perception of herself and her style. Without the ability to purchase clothing regularly, the priority given to clothing shifted. The goal was no longer to buy the most on-trend clothes and was instead to buy the most durable and functional clothing. Many women still despaired at the idea of wearing unfashionable clothing. As a result, newspapers such as the Auckland Star emphasised that “any woman who cannot spare coupons for fresh styles can wear her old coats and dresses and still be in the fashion.” This reduced the pressure women felt to be fashionable, allowing them to adjust to this value-focused mindset that was crucial during the war.

The impact of clothing rationing also required Auckland department stores to change their priorities. Throughout the early 1940s, the department stores continued to sell fashionable clothing, but adjusted their advertising to focus on value in cost and quality of clothing. Through the 1920s and 1930s, Smith and Caughey’s advertising had focused on fashion news and trends. This did not disappear in the 1940s, but was accompanied by emphasis on being their 60 year history as being “famous for value.” Both John Court Limited and George Courts ramped up their advertising of sales, bragging of “further sale price reductions” and “great summer fashion sales.” Milne and Choyce emphasised colours like navy as a “year-round asset” and black as “perennial, versatile, and smart” to allow Auckland women to feel confident in their stashes of long-lasting and wearable clothing. Farmers’ continued to hold their fashion parades during and after wartime in an effort to draw women to the store in a time where their primary concerns were outside of the fashion world. Clothes were to be “washable, serviceable, easily made and very pretty” and stores provided clothing that fit this description, along with the materials needed for women to make it themselves. This meant that despite the chaos of the world, Farmers’ attempted to keep some fun in the fashion and shopping experience. This built on value differently, adding novelty where it was not expected.

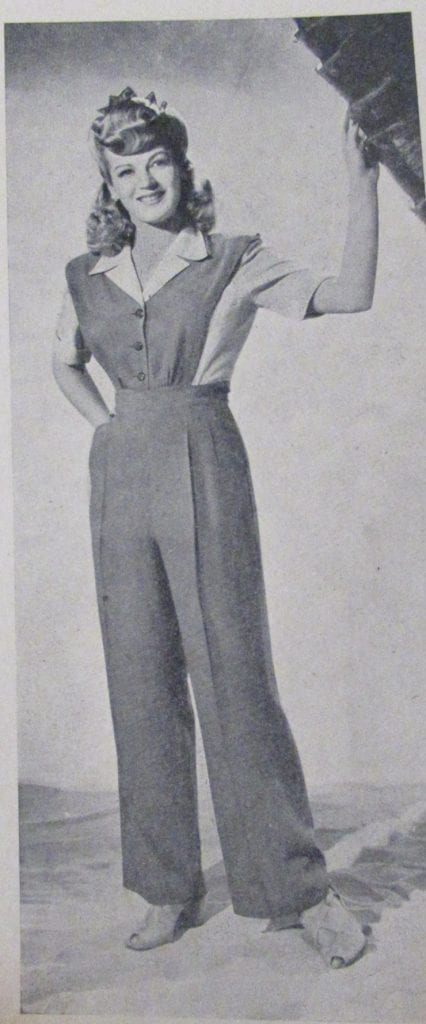

Image 2: An example of a wearable dress in The Mirror, with the pattern provided for free as part of their monthly pattern service. (Image by unknown for The Mirror, January 1945).

What Women Wore

Not even a world war could prevent Auckland women from striving to be fashionable. The Mirror (the key magazine for Auckland women) discussed the latest trends, and Auckland’s department stores continued to provide what people wanted to wear. While the 1940s did see a decline in fashion content in magazines compared to the 1930s, the Mirror made sure to continue with its renowned pattern service, and still featured images of the most popular styles from overseas.

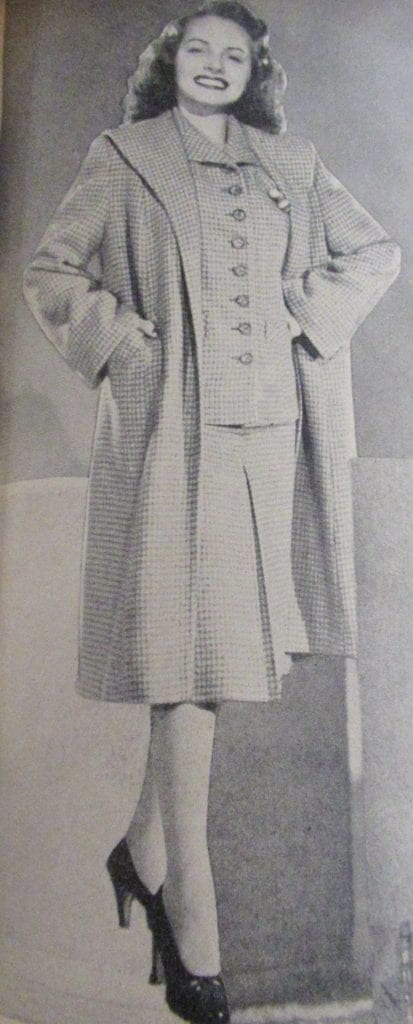

The key word to describe most 1940s fashion is ‘utilitarian’. Fashion not only needed to look good, but also had to be highly functional – 1940s fashion was made to be worn and had accommodations such as pockets that made clothing comfortable and useful. The Mirror decreed that “the smartest women wear suits for almost every occasion” and boasted that “everybody loves the freedom of a button-down-the-front dress,” placing emphasis on the styles that allowed the most movement.

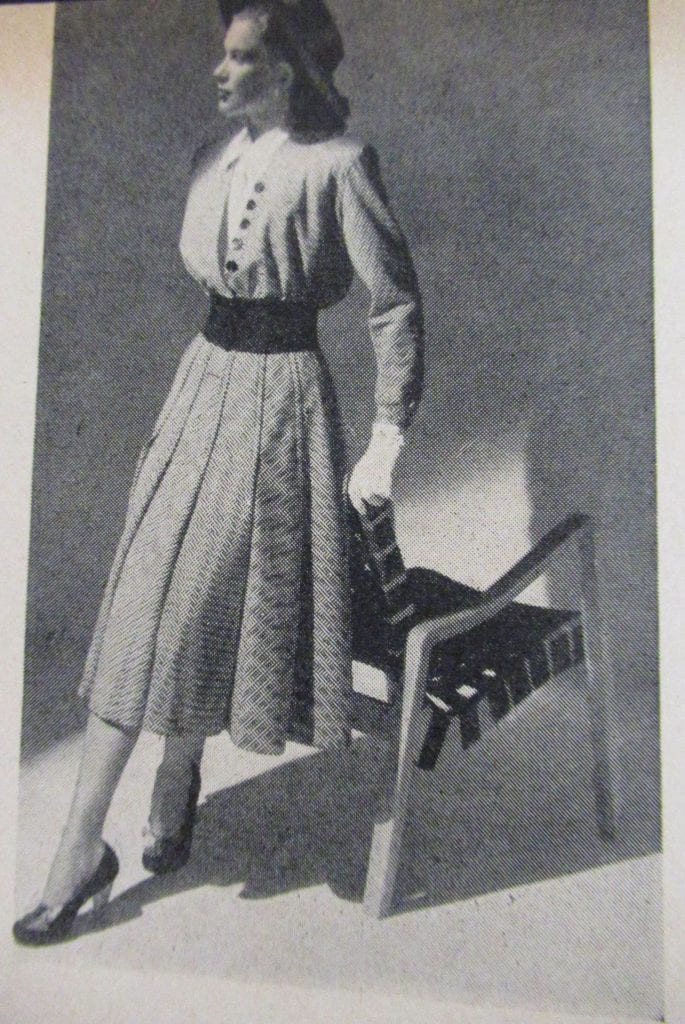

Hemlines varied over the course of the decade. According to one Mirror article, “the length of women’s skirts is world news,” and the contents of this magazine proved this to be true. The beginning of the 1940s saw significantly shorter skirts than the 1930s, likely due to war-imposed fabric shortages. However, skirt lengths grew again by the end of the decade, as more fabric was available post-War and designers wanted to put it to use. “Pathetically poor quality fabrics” due to wartime scarcity often meant that clothing was just what the fabric could cope with. At some points, this meant skirts became fuller as this is what the material could handle the best, while at other times it meant that skirts became shorter so that less fabric had to be used. The clothing styles were at the whim of the fabric that was available.

There was also immense progress for women in this time. Half a century of progress had meant that women had gained more autonomy over their decisions, leading to increased variety in clothing. With women having more say on how to spend their time and money, this meant that they were able to purchase the clothes that they personally saw as necessary. The 1940s saw a new “elasticity of choices of styles never before available to the fashion-conscious woman.” However, women were still urged to be up-to-date with the new fashion trends, as post-war stability began to make this possible.

Image 3: A display of the variation in dress styles of the late 1940s – both wider, more feminine skirts, and more narrow pencil skirts were popular during this time period. (Image by unknown for The Mirror, February 1948).

These revolutionary changes were seen in many different clothing items. A December 1944 issue of The Mirror marks the first sighting of the bikini, which apparently came about when women “could cut no more of the top or bottom of her costume, so took the only logical course: she chopped a piece out of the middle.” While this was not the most common style, it still marked a significant departure from the conservative styles of all previous decades. Furthermore, this decade marked trousers becoming a more acceptable everyday item of clothing for women. In 1940, Smith and Caughey advertised a new divided skirt (which was essentially a wide-leg pant), which was to be worn in a sports context. By the end of the decade, pants were slowly becoming a more functional staple in wardrobes as women became more active, with activities such as riding bikes becoming more commonplace.

Image 4: A trousers ensemble from 1944, one of the first fashionable examples of trousers. (Image by unknown for The Mirror, December 1944).

The Fashion of Auckland Women – Influenced by the World

The 1930s had Auckland women hearing that their fashion was among the worst in the world. The 1940s saw a shift, with it now discussed that New Zealand women had more important priorities than fashion, explaining why they were not as fashionable as their European counterparts. This decade saw world events interrupting the availability of imported clothing, but Auckland women took advantage of all they had available to them. Fashion magazines such as The Mirror, and department stores in the city meant that there were plenty of fashionable opportunities for Auckland women to take. This allowed them to try their best to be in style using the limited resources they had.

Restrictions of trade and worldwide fabric shortages meant that the first half of the 1940s was much more restricted in terms of international trends reaching New Zealand. Europe was under threat, meaning that Paris was not designing new fashion trends, hence no French trends made it to New Zealand. However, from 1945, after World War II was over, there was a return to desiring the fashions of Europe. 1945 marked “the great French fashion houses preparing designs for export [to New Zealand], for the first time since 1940.”

Image 5: A model wearing a 1947 Christian Dior dress, featuring a wider and longer skirt for “exaggerating the feminine line of the figure.” (Image by unknown for The Mirror, November 1947).

From this point forward, the fashions of the world were re-introduced to Auckland. Milne and Choyce discussed the shared desire for functional clothes in London, Paris and New York – the three western fashion centres of the world. The fashions from these cities were detailed, including Paris, where “clothes have become soberer since the liberation,” London, where “wardrobes are crippled by stringent privations,” and New York, where “American fashion reflects a mood impatient with fuss.” This reflected the general worldwide feel of the late 1940s – a continued desire to focus on value and utility in clothing.

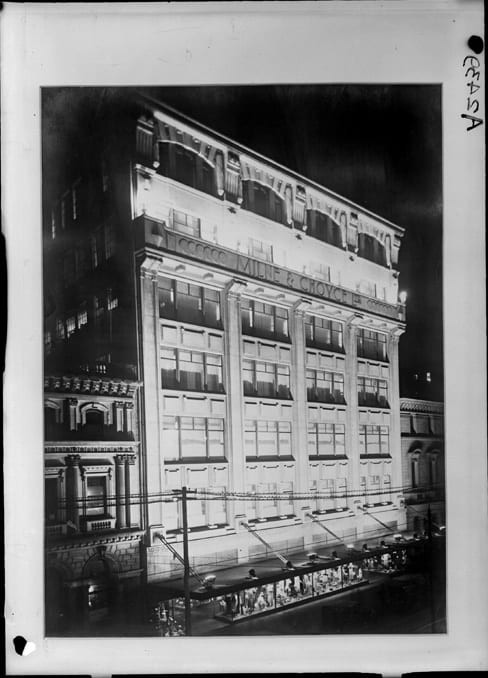

Later in the decade, fashionable items created for their looks began to reappear. Milne and Choyce used their large windows on Queen Street to display these new fashions. M&C “made fashion history” in their unique displays the fashion of Paris in their windows, making them extra visible for Auckland women. Designers such as Christian Dior and Balenciaga were making waves over in Paris, and M&C was revolutionary in displaying these “up-to-the-minute designs from leading French experts.”

Image 6: The Milne and Choyce building on Queen Street in 1944. (Image by Clifton Firth from Auckland Libraries Heritage Images Collection.)

From the 1940s, Hollywood also began to be an influential place for fashion. The Mirror showcased this, with displays in their magazine including pictures of Hollywood stars in the latest fashions. Yet, Paris reigned supreme, with even designers in New York trying to go to Paris to see the fashions. Just like in the 1920s and 1930s, London was also a key fashion destination. However, as stated by the Auckland Star, “as long as Paris is there, Paris will take precedence over London.”

Image 7: Janet Blair of Colombia Pictures, as featured in The Mirror in May 1945 in an attempt to advertise Hollywood fashion to New Zealand women. (Image by Columbia Pictures for The Mirror, May 1945.)

The Future of Fashion

Thus, the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s saw an intense evolution of women’s fashion. At the beginning of this time period, skirts were floor-length and all skin was conservatively covered. At the end of the period, there were options on how to dress. In considering the changes in fashion during the 20th century, it provides an interesting contrast to look at the 21st century.

Hemlines have changed dramatically over time. Skirts were shorter in the 1920s, longer in the 1930s, and varied during the 1940s – but always remained firmly below the knee. In 2023, skirts of every shape, size, and length are seen and worn. Fashion freedom has exploded, even compared to the women in the 1940s was believed that had an explosion in variety.

These decades saw the beginning of trend cycles. Through the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, women and magazines alike thought trends were moving fast, but compared to today, they were snail-like. Trends in 2023 breeze past, resulting in fast fashion unethically dominating most young women’s wardrobes – even with growing calls to end this unethical fashion movement. Hence, it provides an interesting insight to look back.

The 1920s-1940s centred Paris as the home of fashion, accompanied by London, New York and later Hollywood. To women in Auckland, so far away from these big cities, department stores and magazines such as The Mirror provided gateways to these big ideas and grand clothing designs.

The 20th century saw the birth of the department store as a gateway to fashion, but it also saw its decline. The rise of specialised clothing stores and the reduction of women making their own clothes contributed to this decline. John Court closed in 1972, George Courts closed in 1998, Milne & Choyce closed in 1999, and Rendells later closed in 2006. Only Smith and Caughey and Farmers’ remain in operation today – Farmers’ as a country-wide mega department store, and Smith and Caughey with two stores in Auckland, one in its original opening location. As online shopping grows more popular than ever before, it is interesting to see how the future of fashion will change women’s purchasing habits.

The Mirror provided interesting fashion insights throughout the 1920s-1940s, some of which can be helpful for women today such as the advice “to avoid anything of an extreme, or slightly ludicrous appearance, for it will not remain long in fashion.” For audiences in the 1940s, this was an important message in economically uncertain times. For audiences in the 2020s, this message may hold the same importance. As the world continues to change, women’s fashion provides a revealing lens through which one can see changing attitudes about consumerism, conservatism, and clothing.

As a whole, the 1920s to 1940s illustrate that fashion is, and always has been, important to women. This was the time period where fashion became a global industry, combining the ideas of fashion designers and women to create clothing.

As New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland took on a role as a fashion frontrunner, exhibiting this through housing women’s magazines and large department stores. Women in Auckland wanted to be fashionable, and it was important for them to have the clothing available to present this fashionable image. The 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s have exhibited to us that Auckland women were, and continue to be, fashionable.