Part Three

The Rise of Marching in Auckland: A Healthy Sport for Girls or Hidden Militarism?

Part Four

Marching: Aesthetics and Uniformity

by Katia Kennedy*

“Some squads marched with the precision of soldiers, chins well up, shoulders back, arms a-swing in quite the military manner.”

Figure 1: A team of marching girls on parade in Waiuku. (Unknown photographer, Marching Girls, Waiuku, 1960s, circa 1960. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/41336)

For most, the competitive sport of women’s marching likely seems like a figment of one’s imagination or for others, a relic of the past. However, marching– a precursor to cheerleading and band marching– is still around, though on a much smaller scale than in the past century. Forgotten now or not, marching burst into the public eye in the late 1940s and took Auckland (and the rest of New Zealand) by storm.

Marching is a uniquely New Zealand sport that emerged in the late 1920s but found its footing in the backdrop of the Depression in the 1930s. In an attempt to help people escape the bleak reality of the time, team sports were encouraged. Unfortunately for girls, the main team sports they played during this time was basketball and hockey—both winter sports. Those that wanted to participate in sports year round found a solution in marching.

What is marching?

It began as a recreational activity, loosely based on the Army Manual of Elementary Drill. Teams of at least nine girls would execute moves from the Drill to brass or pipe band music. Judging took place mostly by ranking general appearance and execution of movements. Since the early days, the sport has evolved with more precise march patterns, different music, and a more refined judging system.

Fitness and physical exercise for girls seems to have been promoted during the mid to late 1920s. Auckland in particular began to promote marching through annual inter-house sporting carnivals held at Carlaw Park. Girls from various businesses would don distinctive colours and patterns and compete in the carnivals. The first of its kind was held in 1924. These carnivals grew rapidly in popularity. By 1928, 500 girls took part– 200 more than had in 1925.

Already popular in Auckland, World War Two saw a rise in the sport’s profile nation-wide. One reason for the growing interest in marching was the increase in girls and women entering the workforce, giving more businesses opportunities to enter into the Inter-House Carnivals. Another, and perhaps the most important, was that the sport attracted returning Army Officers and Drill Sergeants. These men became coaches or judges, lending the sport a credibility it did not previously have. In 1941, the North Island Girls’ Marching Association was formed with the cooperation of the Defence Department. Close military association would continue through the marching girls’ history. Under the North Island Association, regional centres were formed and under the Auckland Centre, teams like the Point England Swiftfoots and Papatoetoe Highlanders competed.

Outside of competitions, marching girls were a common spectacle for entertainment at official events, like school galas and church functions. These occasions often showcased more “glamour-oriented” marching than was presented in competitive environments. Marching teams also commonly performed guards of honour at team members’ weddings and in parades, such as in Auckland Domain during the Queen’s visit in 1963.

Figure 2: Crowd’s watching marching team during the Queen’s visit in 1963. (Rupert Pike, The Queen’s Visit to Auckland, 1963. 1963-02. Photograph. Rupert Pike Collection. https://digitalnz.org/records/44671603/the-queens-visit-to-auckland-1963.)

Why did girls march?

Marching girls competed in three different categories: midget, junior and senior. The midget grade consisted of girls aged 8-12 and the junior grade was for girls 12-15 years of age. There was no age limit for senior teams. The most common reason given as to why girls joined and continued to participate in marching teams was the fellowship they found. Friendship among the girls was actively encouraged and for women who were no longer school-aged, this would have been an acceptable way to socialise and network with other women.

Another lure was the prospect of travel. Marching teams travelled for regional competitions and some more successful teams travelled overseas once the sport had spread to other countries. A number of successful Auckland teams have been recorded travelling consistently both within New Zealand and overseas. One of Auckland’s most decorated teams, the Scottish Hussars for example, claimed the Senior New Zealand Championship title for the fourth time in 1958 in Invercargill.

It appears that Australia was the most common place to invite Auckland teams to compete. The Point England Swiftfoots Marching Girls team travelled to Australia to compete in 1961 and again in 1965. Although it remains unclear whether the Balmoral Marching Team actually left New Zealand, they were given a list of rules to follow for a proposed tour of Australia in 1976. These rules were mostly concerning the behaviour of the marching girls on tour and will be covered further in the next article.

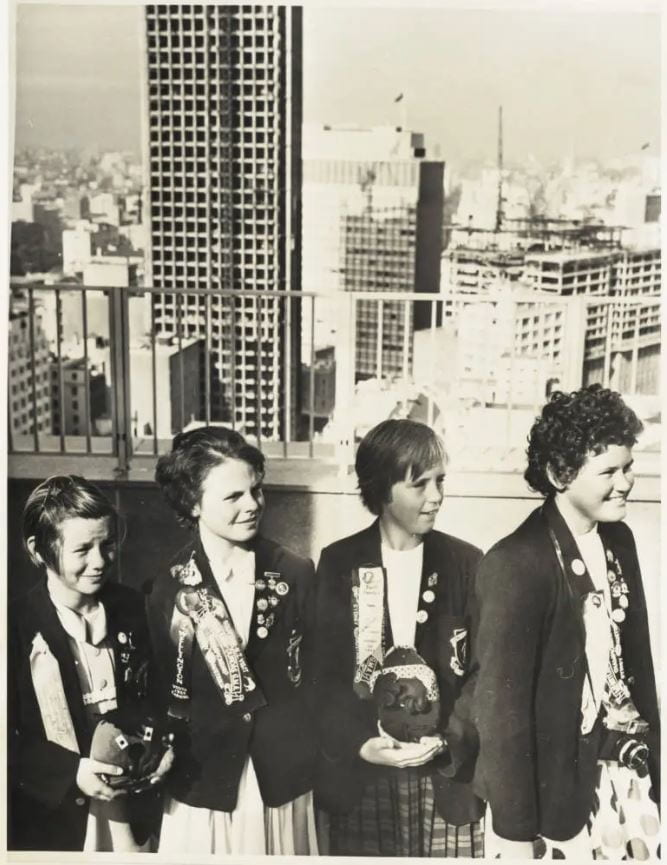

Figure 3: members of the Point England Swiftfoot Marching Girls in Sydney. (Unknown photographer. Swiftfoot Marching Girls in Sydney, 1965. 1965. Photograph. Mt Wellington Public Library Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/92264.)

Military connections

Following the end of the war, the marching competitions were judged almost entirely by Army personnel. Wanting to leave behind the dullness and stress of the war years, an effort was made to brighten up the competitions. This largely appeared in the form of costumes. Indeed, many photographs provide glimpses into how colourful competition days would have been.

Figure 4: A North Shore Girls Marching Association team in uniform. (Unknown photographer. North Shore Girls Marching Association team. 1980-1989. East Coast Bays Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/31955.)

Many reports made by people watching marching displays also note the colourful nature of the sport. One such poem appeared in the Quick March magazine:

“The town is full of colour now

The marching girls are here;

They only bring their pretty selves—

they need no marching gear.

[…] From Auckland with Instructor Smeal

The bonny wee Hussars

(The pride of Auckland City and

Their loving ma’s and pa’s)

Another title seek to win—

They rank as topmost stars.”

Despite the outward appearance, marching retained its distinctive militaristic style. The need for precision and synchronised execution of movements like the various pivots, inclines and counter-marches (see glossary below) were originally based on the Army Manual of Elementary Drill. Smartness was promoted and although military discipline was not encouraged, it was ‘suggested’ to ensure a high standard of drill results. The whistles and commands used by the team’s Leader were also distinctly martial. Such commands needed to be presented first with a cautionary directive, followed by a one syllable executive command, delivered sharply. For example, commands like “atten-TION” and “team—HALT” were frequently heard. Once the “atten-TION” command was issued a marching girl was expected to do the following:

“Spring into the following position: Heels together and in line. Feet turned out at an angle of about 30 degrees […] Knees straight. Body erect and carried evenly over both thighs with the shoulders […] down and moderately back. Arms hanging from shoulders as straight as the natural bend of the arm will permit. Wrists straight. Hands closed but not clenched. Thumb lying over the crook of the index finger. Back of the closed fingers lightly brushing the thigh. Thumb level with the outside centre of the thigh. Neck erect. Head balanced evenly on the neck and not poked forward, eyes looking their own height and straight to the front. The weight of the body should be balanced on both feet and evenly distributed between the fore part of the feet and the heels. Breathing should not in any way be restricted, and no part of the body should be drawn in or pushed out.”

Figure 5: An unidentified marching girl standing at attention. (Rykenberg Photography. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/76857/rec/206)

The highly technical nature of the sport drew criticism from some but was hotly defended by those involved. The military influence on the sport was noted by many. In the monthly Quick March magazine, adverts for the New Zealand Women’s Royal Army Corps frequently appeared to conclude monthly issues with the tagline: “As Marching Girls, you know the value of teamwork.”

To an uninitiated outsider, the precise, synchronised movements indeed screams militarism. One particular New York Times article, where Auckland’s Scottish Hussars sat front and centre, took this stance. The author did not hold back in his criticism of the sport, acknowledging the large following marching had attracted but described it as an “unnatural, unfeminine” and ultimately an outlet of “hidden fascism.” This article sparked outrage from associations across the country. The ‘cult-like’ nature of marching displays was also noted by writers A.R.D Fairburn and Bruce Mason who critiqued the sport for its militaristic undertones. Indeed, there is little to obstruct even the casual viewer from making such a connection. Although it has evolved since its inception, the origins of the sport are hidden only beneath the loud music and bright costumes.

Health of marching girls

As with most sports women attempted to participate in in the late 1920s, men who seemed concerned for the health of the women involved followed any sporting developments. One such onlooker wrote to the New Zealand Herald in 1927, expressing concern that by throwing their weight back, marching girls would suffer from “stretched abdominal muscles,” “hollow backs” and “displacement of internal organs.” This onlooker appears to be in the minority with their critique on the techniques overshadowed by the many praising the sport’s promotion of healthy young women.

One of the major draws of the sport was the promise of exercise for the girls and women competing. Marching was neither too demanding nor too strenuous that it would draw criticism for being unlady-like. It also had the benefit of developing a “fine, upright carriage” and worked as a leg-strengthener. The benefits of the sport did not come by accident. In Auckland particularly, there was an attempt to improve and promote good posture by sending marching captains to a series of lectures in 1938 ahead of the annual sports day at Carlaw park.

Medical professionals recommended the sport due to marching being available to anyone who could walk without assistance (although the intense judging of the uniformity of teams begs the question of whether ableist undertones permeated the sport).

Parents of marching girls were just as aware of the health benefits of the sport. One mother wrote to the Quick March magazine singing the sports’ praises, stating that when her daughter began marching “her legs were distinctly crooked, but […] now they are almost straight and she is in much better health.” An emphasis was placed on instructors ensuring the physical fitness of their marching girls. At the highest levels, a series of lectures was attended by Pam Inder (Member of the New Zealand Marching Association Instructional Committee) and the notes sent to Paul J. Phillipe (Instructional Co-ordinator of the N.Z.M.A in 1976) on the best methods of training and how to improve physical fitness with the intention of incorporating such techniques into training manuals for instructors across the country.

Much of the praise marching received in the 1950s seems to stem from its affirmation of the ‘ideal’ female figure. Alongside the intense curating and judging of marching girls’ appearances, reports referring to marching often refer to the attractiveness of the girl’s participating. For example, when the New York Times article on the fascist nature of marching was published, marching associations and centres around New Zealand argued that all marching was only guilty of producing healthy girls and women. In fact, one such line published in the Quick March and distributed nation-wide, stated that the sport, “so vigorous an exercise might so embellish many sylph-like figure with muscle as to create a new generation of rolling-pin dictators in the kitchen.” Marching, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, provided a sphere for women to inhabit unimpeded because of its reaffirmation of gender roles and the nuclear family. Perhaps this is why marching held such a sway over girls and women in New Zealand when cricket struggled to draw a crowd. This also may be why it has slipped from public favour into oblivion in recent decades.

Although marching was created in New Zealand and enjoyed huge popularity in Auckland, it attracted attention from around the globe. The extremely technical side of the sport, coupled with its overt military backgrounds drew criticism from some but these were ultimately overshadowed by both the health benefits of the sport and the enjoyment of those participating. As the sport developed, an emphasis was placed on judging, including meticulous inspection the general appearance of the girls competing, which may have been one of the contributing factors to its eventual decline out of the public eye. As we shall see in the next article in this series, the technical aspect of marching was only half of the intricacies of the sport. The other half was extremely and meticulously driven by the aesthetics of competitive marching.