Part One

Prisoners to Patients – the Pre-Asylum State of Mental Health Care in Auckland

by Sasha Finer*

A glance at the report of the inquest will show the evil of committing people of diseased mind to either the gaol or hospital. If any one ever required special treatment – medical, hygienic, or domestic – it is the lunatic.

Colonist, 31 March 1863.

The earliest piece of legislation in New Zealand concerning the mentally ill was the Lunatics Ordinance of 1846, which aimed to “make provision for the safe custody of and prevention of crime being committed by persons insane”. This addressed what was essentially the primary social concern regarding the insane at the time – that as individuals who deviated significantly from the behavioural norm, they posed a threat to ‘normal’ members of society. The solution to assuage this fear – as exemplified in both the Ordinance and the concurrent development in Britain of the Victorian ‘lunatic asylum’ – was to remove and confine those exhibiting symptoms of madness from society for the safety of others, and to a lesser extent themselves.

In order to do this, the Ordinance provided that after a process of certification it would be lawful to commit a person found to be “a dangerous lunatic or a dangerous idiot” to a gaol or public hospital, or otherwise “some public colonial lunatic asylum”. The issue with this, as pointed out with some derision by The New Zealander in 1849, was that no iteration of the latter existed in the entirety of the country even three years on from the passing of the Ordinance. In fact, none would exist for a while yet. Another five years would pass before the opening of the Karori Lunatic Asylum in Wellington, the first public lunatic asylum existing as an independent facility in New Zealand, which was established as late as 1854.

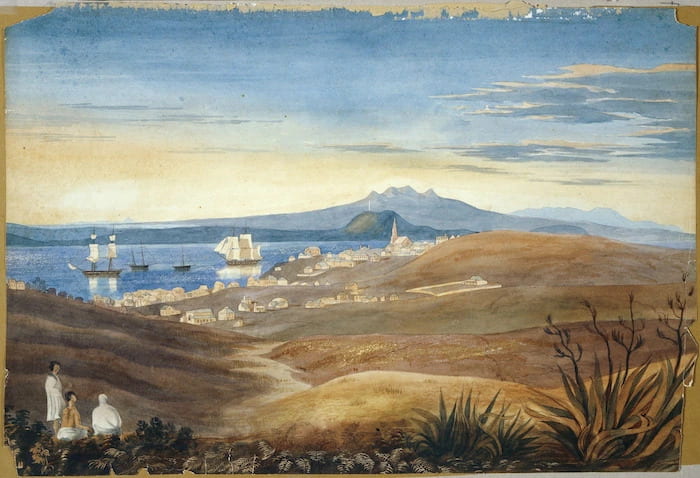

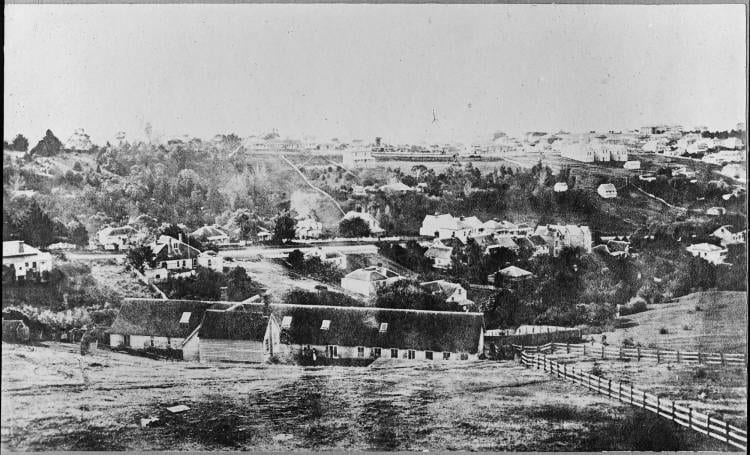

Figure 1: A painting depicting the nascent city of Auckland around the time the Lunatics Ordinance was passed. This view is from roughly around the top of Queen Street, which follows the path of the stream down into the midground of the painting. The building to the right with the large rectangular enclosure is Government House, located today on the University of Auckland campus. Ashworth, Edward. Auckland looking North. [1843?]. Ref: A-275-007. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

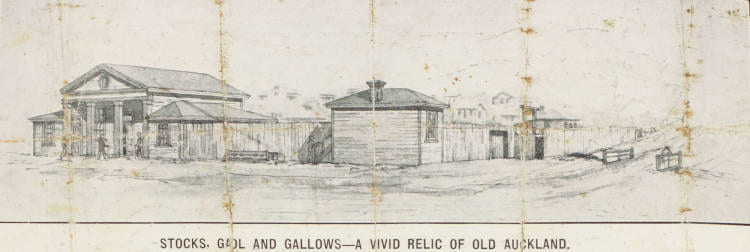

In the rapidly-growing province of Auckland this meant that for a good part of the 19th century, those deemed to be insane were confined within either the city gaol (which existed as a collection of buildings and a courthouse at the corner of Queen and Victoria Streets between 1842 and 1865) or at the hospital in Grafton. Gaol records are scarce until the opening of the Mt Eden Stockade in 1856, and it is difficult to tell just how common it was for lunatics to be held at the gaol. It is possible that a ‘pauper asylum’ existed as a separate wing or building attached to the gaol, as was the case in Wellington; while some secondary source material indicates that this may have been the case, there is little definite evidence for it.

Regardless, it is certain that some of Auckland’s lunatics were imprisoned at the gaol – in 1842 a man who was ‘“wandering about the town in a state of mental imbecility – with no means of support – no employment, and a nuisance to the respectable inhabitants of this town”’ was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment in the city gaol. The Auckland Times in 1843 reports the death of a man in the gaol “under the dreadful affliction of lunacy… [who] died by the visitation of God”, and in 1848 The New Zealander notes a coroner’s inquest held upon the death of “William Barr, a lunatic in the gaol of Auckland”.

A rendering of the Auckland City Gaol at the corner of Queen Street and Victoria Street West, as it stood circa 1850. Visible (L-R) are the courthouse, guardroom, stocks, gaol, and gallows. Today this site is occupied by the ANZ building. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection, NZG-19101207-0032b-01.

By 1849, public concern in Auckland was rising regarding the appropriate treatment of the insane. The city gaol as a holding place was described in an article in The New Zealander as a place in which there was “no possibility of placing the afflicted persons under such care as affection and common humanity would suggest”, and there were concerns expressed regarding the increasing frequency of “mental maladies” within the community. A tipping point had been reached, and the overwhelming public sentiment in Auckland was that a proper facility was sorely needed “for the application of treatment, either medical or moral, by which they [the insane] may be restored to their reason and to society”. Several influential members of the community had signed a petition presented to Governor Grey citing the Lunatics Ordinance and calling for immediate action towards instituting an asylum or similar facility in Auckland; it would serve, they argued, as important a need as that of any ordinary hospital. The New Zealander proposed some form of subscription drive to fund the building of the asylum.

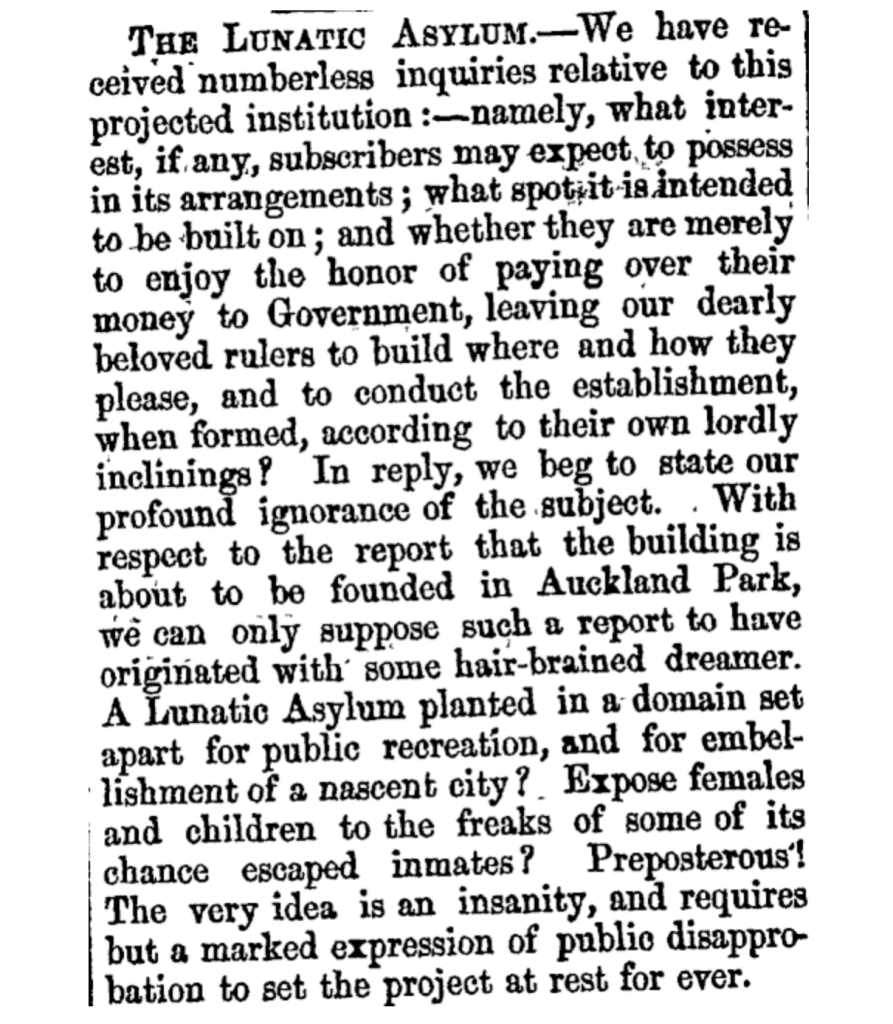

The pleas of the community did not go unheard. A year on, preliminary meetings were being held regarding the establishment of some kind of facility for holding and treating “the cases of insanity, which, as is well known, have unhappily been not very infrequent in this colony”. Governor George Grey was consulted and, as a supporter of the project, backed the “most convenient and suitable” proposal of constructing a detached building on the hospital grounds within the Auckland Domain, which was the generally agreed upon site at the time.

The Daily Southern Cross demonstrates that the proposed site on the hospital grounds was not exactly universally lauded. (What we now know as the Auckland Domain had been officially dubbed ‘Auckland Park’ by Governor FitzRoy in 1844.) Daily Southern Cross, 8 August 1851. Accessed via Papers Past.

There was, however, a brief and highly contentious instance of opposition from the Auckland Borough Council when some members raised objections to building an asylum on the hospital site, which was noted as “extremely ill-placed” and notoriously unsuitable for even its initial purpose. Personal opinions may have factored into these objections, too – many were clearly uncomfortable with having an asylum and its ‘dangerous lunatics’ situated so centrally. But issues with funding meant it was impossible to change the site without significantly delaying the build at best – or putting a stop to the endeavour entirely at worst. As a consequence, passions rose in the meeting hall as one member “[arose] with flashing eye… to denounce the amendment”, and “hurl[ed] his indignant thunders against Government Officers and residents whose selfish inhumanity sought to put a stop to the erection of a humane and much wanted establishment”. In the end the objection was overturned within the span of four days and the building of the asylum on the hospital grounds commenced in 1852. It was understood that with the facility’s location the asylum would exist as a part of the general hospital, and could therefore be maintained financially with the hospital endowments.

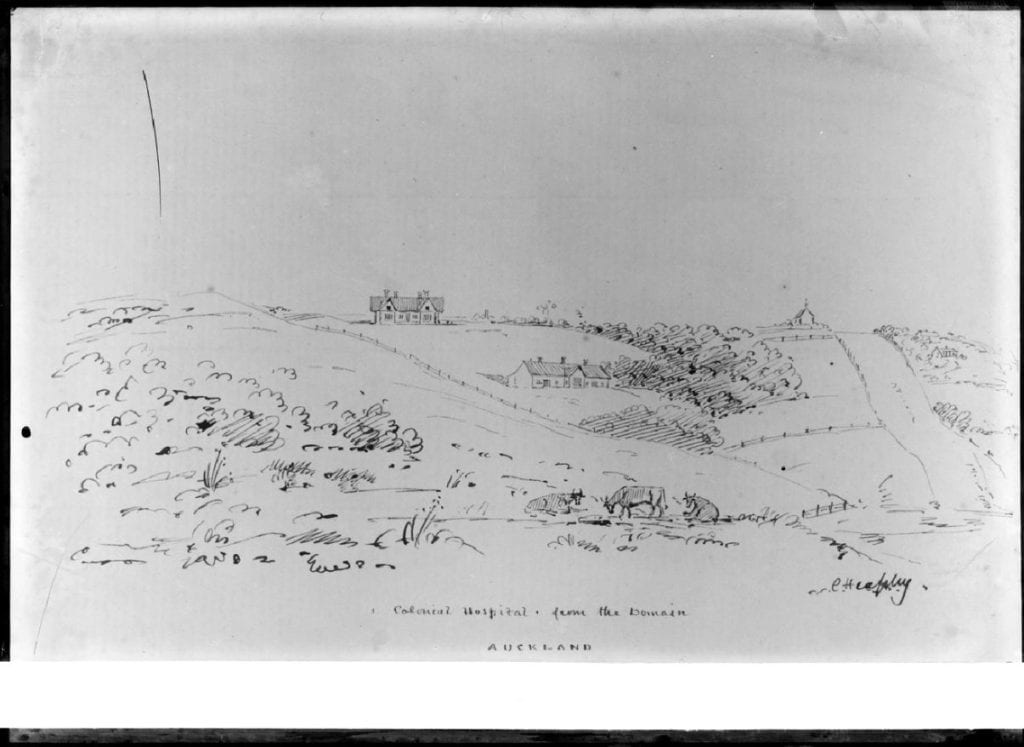

A sketch done by Charles Heaphy circa 1850s showing the hospital building (top left, on the horizon line) and the hospital asylum (slightly below and to the right of the hospital). The buildings are viewed here from the domain behind the hospital grounds; Grafton Gully has been rendered as an area of dense bush centre-right, and the road visible on the very right is probably Symonds Street. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

Although it would turn out to be a short-lived facility, the construction of the hospital asylum provides an interesting snapshot into ideas about space and mental health treatment at the time, as exemplified in a letter written by the Assistant Colonial Surgeon at the time –Henry John Andrews – to the Auckland Provincial Council. In the letter, which concerns a proposed enclosure around the asylum building, Andrews petitioned strongly for considering what he called the “moral treatment of the insane”. The walls of the enclosure, he argued, should be erected “in such a manner as to inclose [sic] some of the trees or shrubs… by an arrangement of paths, monotony might to a great degree be avoided”. He was of the firm opinion that variation in surroundings should be taken into account when constructing spaces for the patients, as not only a comfort but also “a powerful means of cure”.

Andrews’ letter reflects heavily in its attitude and also directly references by name the English psychiatrist John Conolly, who had some 20 years earlier significantly transformed the treatment of asylum patients in England by introducing the principle of non-restraint. Conolly had also recently published The Construction and Government of Lunatic Asylums and Hospitals for the Insane, a manual with a considerable section devoted to the benefits of airing courts, grounds, and outdoor activities in the treatment of the insane. He believed, as Andrews paraphrased, that “nothing tends more powerfully to depress the mind, than the monotonous bare walls of which frequently surround such enclosures”. This spatial consideration in the construction of the hospital asylum was reflective of slowly-changing Victorian attitudes to mental illness at the time – considering treatment over mere confinement – and the influence that those Victorian attitudes and practices had on the establishment of lunatic asylums in New Zealand.

The hospital asylum building, still standing circa 1880. It is viewed here as it would have been seen from the ‘new’ hospital building when looking out over Grafton Gully. The post-and-paling fence visible to the right of and just below the building is likely the enclosure that Andrews advocated so fiercely for. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1-W0437. The hospital asylum building, still standing circa 1880. It is viewed here as it would have been seen from the ‘new’ hospital building when looking out over Grafton Gully. The post-and-paling fence visible to the right of and just below the building is likely the enclosure that Andrews advocated so fiercely for. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1-W0437.

Unfortunately Andrew’s tree-filled enclosure was not enough to make the hospital asylum a pleasant facility, nor one which provided for the moral treatment of the insane. Doomed from the beginning by hasty planning and construction, with little time and attention seriously paid to the objections raised by the Auckland Borough Council regarding site choice, these early issues were only aggravated by poor management and an influx of patients well beyond what was anticipated. From its establishment the hospital asylum took in patients from not only the Auckland province but other provinces, such as New Plymouth, which had no sufficient facilities to keep them. When combined with a noted steady increase of people exhibiting symptoms of madness in the Auckland province already, it is no wonder that the facility quickly became overcrowded. The Head Keeper of the asylum in a 1862 letter to the Provincial Surgeon – Thomas Philson – entreated him quite desperately for aid to somehow ease the severe overcrowding and poor conditions at the facility; Philson himself would later refer to the place as “only makeshift – a prison”. At the time overcrowding was so severe that two patients had been removed to the “common jail of Auckland” (possibly the old city gaol, but probably the newer Mt Eden Stockade) for want of space.

An 1863 report which proved to be the death knell for the hospital asylum showed that 49 patients were being kept in a completely insufficient structure built to contain only 33, inciting outrage from the general public. The Colonist wrote of the conditions described by the report:

“The building is overcrowded by one-half; the rain comes pouring in by the roof in wet weather; three or four maniacs are compelled to sleep together in a miserable room, and the handful of keepers are ‘often’ aroused by the shrieks of the weak and helpless, attacked in the night-time by infuriate companions”.

It was clearly a miserable situation. Blame was laid largely at the feet of local politicians, who were accused of overlooking their public duty to the hospital asylum in favour of squandering money on causes likely to get them more votes. With the attention of all the province – if not the country – on the Auckland hospital asylum, the responsibility fell on the Provincial Government to address what was described as “the fruit of years of culpable neglect”.

Fortunately for them, the Provincial Government had seen the writing on the wall of the hospital asylum quite early on and had already begun arrangements for a new asylum to be built – one which would be modelled after the great lunatic asylums of Britain, existing as an independent facility apart from the hospital. Plans for the architecture had been commissioned and imported from England, and the only question was where to build the facility. By 1863, three possible sites had been proposed – the first at Three Kings; the second at Ellerslie; and the third and most favourable situated at Point Chevalier, in the area known as the Whau.