Part Two

From Distant Dream to Reality: The Fight for the Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1926-1951

by Nathan McLeay*

From the mid-1920s, the distant dream of a bridge spanning the Waitematā began to draw rapidly closer to realisation. Public interest in a bridge was formalised in 1926 with the establishment of the Auckland Harbour Bridge Association. Headed by E.G. Skeates, now the Mayor of Birkenhead, the association aggressively pitched its dream of a harbour bridge to those key factions whose support was required if that dream was to be achieved—the general public, local authorities, and central government.

When central government refused its suggestion that a lottery be promoted to raise £1 million toward the cost of a bridge, an infuriated association circulated a petition, to be submitted to parliament, through which residents could show their support for a bridge. In the resolution, formalising the decision to seek public input, association members complained bitterly that the government had offered no potent reasons in refusing to help finance a bridge, and asserted that, given the unquestionable benefits a bridge would bring, a petition was a necessary escalation.[1] The petition, which had amassed 25,000 signatures by the time it was presented to parliament, was a tremendous success: however reluctant the government was to actually build a bridge, such a show of enthusiasm could hardly be ignored. As a result, a royal commission was established to investigate the feasibility of a bridge across the Waitematā.[2] The Harbour Bridge Association had scored a major victory, and a bridge now seemed closer than ever.

The royal commission held sittings in late 1929. Yet, bridge advocates who had pinned their hopes for a breakthrough on this commission would have been sorely disappointed when it published its findings in early 1930. In its report, the commission concluded that the “day had not yet arrived when a bridge was necessary.” [3] In the view of the commission, a harbour bridge would be an expensive and unnecessary luxury given that the existing ferry service provided an “efficient, entirely adequate and extremely cheap” means of crossing the harbour. Despite this negative verdict, the commission’s report included detailed examination of five possible sites for a bridge, indicating a preference for a crossing between Stokes Point and Fanshawe Street. The report even went so far as to outline both the financing and design of a potential bridge, stating that a harbour bridge would ideally be paid for via tolls and include provisions for trams as well as cars and pedestrians.[4]

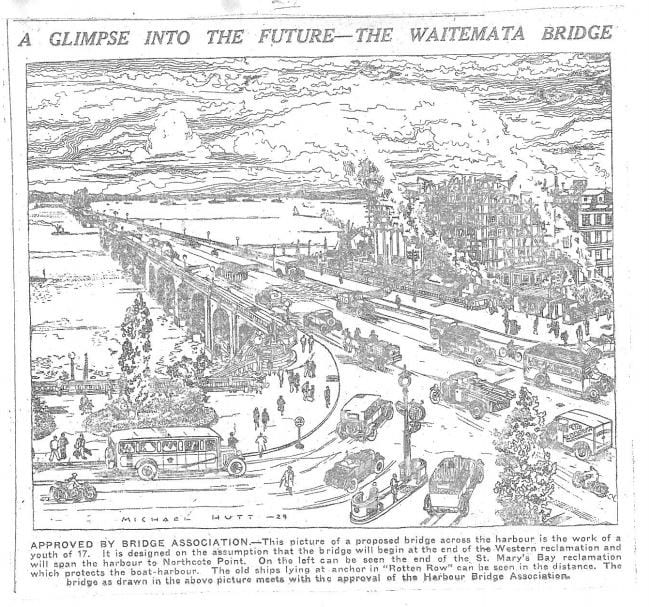

Public enthusiasm for a harbour bridge intensified from the mid-1920s onwards. This depiction of a possible bridge between Northcote Point and the St. Mary’s Bay reclamation, the work of a “youth of 17,” was drawn in 1929 and promoted by the Auckland Harbour Bridge Association. Clipping from a scrapbook concerning early designs for an Auckland harbour bridge found at Research North, Takapuna, in the Auckland Harbour Bridge Archive.

Though the royal commission had ruled it far too soon to consider spending public money on such a project, the findings from the report did not close the door to a bridge completely. The government may have passed on a bridge, but private enterprise was still interested. The Auckland Harbour Bridge Company was founded in late 1930, and the following year was granted a charter to construct a bridge and collect tolls. The company proposed a bridge along the lines suggested in the report of the 1929 commission, but the onset of the Great Depression prevented any further progress.[5]

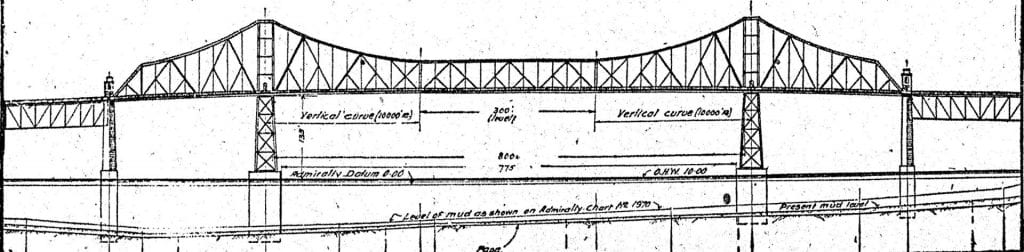

The bridge design proposed by the Auckland Harbour Bridge Company in 1931. Like the 1959 bridge, it would have extended from Stokes Point to Fanshawe Street, and consisted of a steel superstructure resting on concrete pillars. “A section of the proposed Auckland Harbour Bridge, showing the central span,” New Zealand Herald, 20 March, 1931, p.13.

The cause would be renewed once again in 1936, by another mayor of Birkenhead, Ernest J. Osborne. Osborne founded the Waitematā Harbour Bridge Association and lobbied Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage for support. Savage, the MP for Auckland West and a former Auckland councillor, agreed to support a bridge on the condition that a “measure of unanimity” was secured from the affected local bodies. Osborne, however, could not budge the Auckland City Council beyond supporting a harbour link in principal only—rumours flew that the council’s obstinacy was connected to Auckland mayor Ernest Davis’ chairmanship of the Devonport Steam Ferry Company.[6]

The Waitematā Harbour Bridge Association too sought public support for its cause. In 1938 it published a brochure attacking the 1929 commission, arguing that their estimates of trans-harbour traffic increase were “entirely erroneous and pessimistic,” and commenting acidly that “[i]t takes men of vision to build bridges—pessimists prefer obsolete methods of transport.” The brochure also asked Aucklanders to pay a subscription of five shillings to the association, to help its campaign to “close the gap in the highway system.”[7]

The beginning of the Second World War in 1939 and the death of Savage a year later spelled more delays, though by 1943 the Waitematā Bridge Association was advocating for a bridge as an employment-creating project to help rehabilitate returning servicemen. In 1945, the association presented to parliament a petition that led to the appointment of another commission.[8] In contrast to earlier efforts, this time the work of bridge advocates was to bear fruit.

The following year, the 1946 Royal Commission on Trans-Harbour Facilities, under the chairmanship of prominent Wellington lawyer Sir Francis Frazer, sat for five and a half weeks, recording over 1,200 pages of evidence. It found that, based on its projections of future population and traffic growth both in Auckland and on the North Shore, a bridge would become “urgently necessary” within ten to fifteen years, and urged that work begin as soon as possible:

[W]e consider the provision of direct access to the North Shore area as overdue . . . as soon as the specialist staff is available, investigations and economic studies should be put in hand, and the actual date of commencement of the work itself should be determined in the light of the economic conditions prevailing when the designs and specifications are completed.[9]

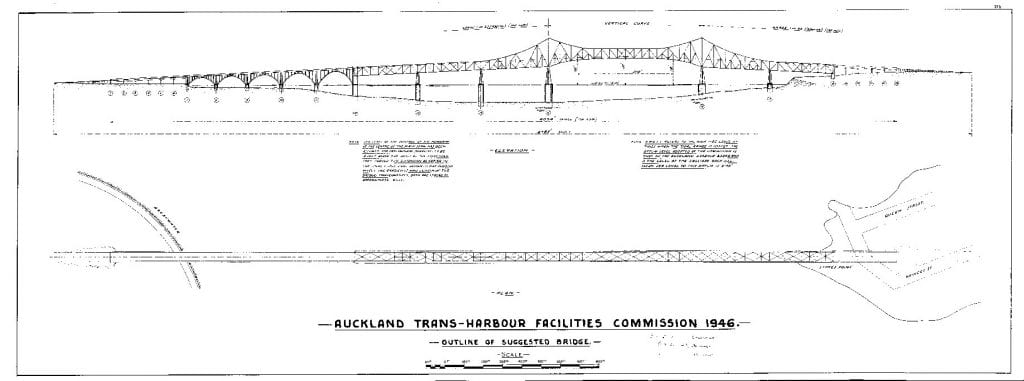

The commission advised that a bridge comprise a four-lane carriageway plus two footpaths, and be erected between Stokes Point and the “western end of Saint Mary’s Bay Boat Harbour.”[10]

An outline of the bridge suggested by the 1946 commission. Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into and Report upon Trans-Harbour Facilities in the Auckland Metropolitan Area and the Approaches Thereto, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, Session 1, D-06, 1 January 1946.

At the commission’s insistence, the Ministry of Works began preliminary work on the bridge, and in 1949 Freeman, Fox & Partners were appointed as consulting engineers for the scheme. On December 1, 1950, the Auckland Harbour Bridge Authority was created by act of parliament. Led by Auckland mayor Sir John Allum, the authority was established with a mandate to “construct, maintain, manage and control a bridge across the Waitemata harbour from Point Erin to Stokes Point.”[11]

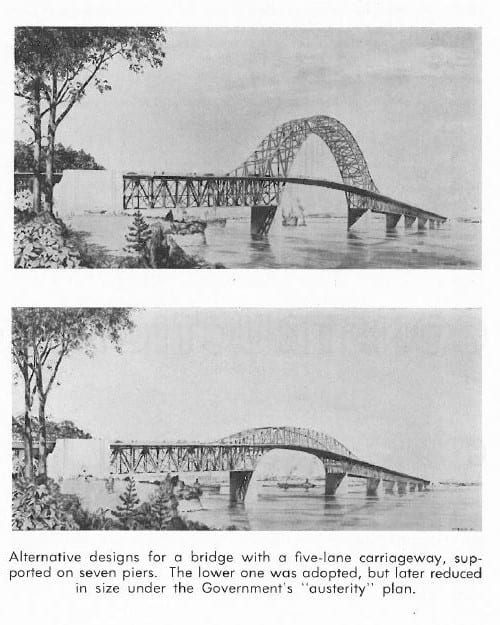

The newly-formed authority wasted no time in setting about its appointed task. It met for the first time on March 8, 1951, and began planning talks with Freeman, Fox & Partners the month following. By May, the authority had decided on its bridge: five traffic lanes, two footpaths, and no railway, at an estimated cost of slightly over £8 million.[12]

Alternative designs for a bridge with a five-lane carriageway and two footpaths, supported on seven piers. The lower design was approved by the Auckland Harbour Bridge Authority in May 1951, but later reduced in size under the government’s “austerity” plan. The Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1951-1961, p.13.

The authority’s decision was not met with unanimous approval. Critics questioned the lack of railway; disparaged the “ugly” proposed design; called for greater North Shore representation on the authority; argued the case for a tunnel instead of a bridge; urged that other public works be given priority—the list of objections, according to a retrospective published by the authority in 1962, was “almost endless.”[13] The omission of a railway was the target of particular scrutiny, with many seeing a rail-less bridge as a missed opportunity. North Shore MP Dean Eyre had expressed as much when, in July 1953, he remarked in parliament:

[i]t is to be hoped that provision is made on the bridge for an electric suburban train . . . bridges are not built every day. It would be inconsiderate of us to require the next generation to build a bridge to take the railway to serve the increased population which will occur . . . I hope that the authorities concerned with the acceptance of the final plans will think of two generations ahead and provide an electric suburban line on the bridge.[14]

Common too was the argument that a harbour bridge should be a low priority for public spending. “[T]here is a remarkable lack of enthusiasm for the project,” declared popular left-wing monthly Here & Now in its February 1953 issue, “and it seems as if one man’s determination to have it built or to bust is keeping it in the foreground, ahead of many more urgent jobs. We admire Sir John Allum’s tenacity, but if the same energy could be diverted to slum clearance or electrification of the suburban railways it might be better spent.”[15] In its April issue that same year, the magazine took another swipe at the bridge, stating that Auckland could have a bridge “only at the expense of other more urgent public works,” and that the cost involved was “hardly warranted to make it easier for car owners on the North Shore to accentuate the city’s parking problem.”[16]

The government, however, was worried less about where the money was being spent, and more about spending it at all. Balking at the cost of authority’s preferred design, the government refused to approve a loan to have it built.[17]

Without financial backing, the project was left in limbo until December 1953, when at last the government gave in, agreeing to fund a bridge provided that the cost of construction did not exceed £5 million. Freeman, Fox & Partners hurriedly produced a new “austerity” plan, deleting the major approach roads and cutting the fifth traffic lane and two footpaths. A contract for the construction of this cheaper bridge was let to a consortium of two British steel construction companies, Cleveland Bridge and Engineering and Dorman Long, in October 1954, and work on the site began in late 1955.[18] After almost a century of speculation and argument, of visionary plans and failed attempts, Auckland was at last going to have its bridge.

*Nathan McLeay was awarded a 2019 Summer Scholarship at The University of Auckland out of a highly competitive field and his award was funded by a Jonathan and Mary Mason Summer Scholarship in Auckland History. His research project explored the history of the Auckland Harbour Bridge.

[1] “Bridge of Waitemata,” Auckland Star, 3 September, 1926, p.10.

[2] Margaret McClure, The Story of Birkenhead, Auckland, 1987, pp.175-77.

[3] Waitemata Harbour Transit Facilities (Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire Into), Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, Session 1, H-35, 1 January, 1930, p.14.

[4] ibid., pp.17-24.

[5] Auckland Harbour Bridge Association, The Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1951-1961, Auckland, 1962, p.4.

[6] Graham Bush, From Survival to Revival: Auckland’s Public Transport since 1860, Wellington, 2014, p.127.

[7] “Bridging gap took men of vision,” North Shore Times Advertiser, 15 May 1979, page unknown: clipping found at Research North, Takapuna, Auckland, in Auckland Harbour Bridge VFL, 642.2, Volume 2, AUC; Waitematā Harbour Bridge Association, “Proposed Auckland Harbour Bridge,” Auckland, 1938, document found at Research North, Takapuna, in the Auckland Harbour Bridge Archive.

[8] The Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1951-1961, p.5.

[9] Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into and Report upon Trans-Harbour Facilities in the Auckland Metropolitan Area and the Approaches Thereto, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, Session 1, D-06, 1 January 1946, p.6, pp.34-35.

[10] ibid., p.7.

[11] The Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1951-1961, p.10.

[12] ibid., pp.11-12.

[13] ibid., p.12.

[14] New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), July 6, 1953, p.198.

[15] Here & Now, “Notes,” February 1953, p.4.

[16] Here & Now, “Notes,” April 1953, pp.4-5.

[17] The Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1951-1961, p.12-15.

[18] ibid.