Part Three

Two Powerful Voices in Diverse Communities

by Brooke Stevenson*

Mere Newton and Mary Dreaver were two women in politics in the 1930s that commanded an influential were voice within their respective communities. On the 28th August 1939, Mere Newton suspended standing orders of the Onehunga Borough Council Meeting to highlight the need for better Māori housing in their community.[1] No doubt Newton was influenced by her experiences eight years prior when she was on the forefront of helping the plight of those impacted by the Māngere housing crisis where Māori families, who were disproportionately affected, were living in horrendous conditions.

A few years later, Mary Dreaver stood up in parliament and urged members of the house to consider allocating money to build a school for obstetricians and gynaecologists in Auckland in order to curb the number of deaths during childbirth. No doubt Dreaver was influenced by her eight years on the Auckland Hospital Board, and her relatively underprivileged upbringing with a Progressive father-figure.

The directions that Newton and Dreaver’s politics took were shaped by their respective social and cultural backgrounds, despite their both ending up as hard working members of the Labour movement. Newton was closely connected to the Māori community and this cultural identity was evident through much of her politics during her time on the Onehunga Borough Council and secretary of the Epsom-Oak Labour Branch of the Labour Party. Dreaver, by comparison, grew up as a working-class European, and largely centred her politics around Progressive Labour ideology, in particular, showing a political interest in the betterment of healthcare.

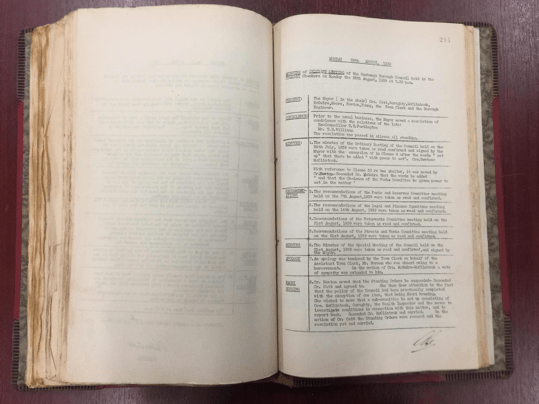

Photos of the Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books of Cr. Newton suspending standing orders to highlight the failure of the Council to attend to the matter of Māori housing in Onehunga. Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books, 28th August 1939, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 20, Auckland Council Archives.

A Voice for Māori

Newton had two successful terms as a member of the Onehunga Borough Council in 1938-41 and 1941- 44. Exploring the minute books of the Onehunga Council from this time period, a strong theme emerges concerning Newton’s work on the Council – the betterment of Māori in the community. On the 28th August 1939, Newton moved that standing orders be suspended. The minute book read:

She then drew attention to the fact that the policy of the Council had been practically completed with the exception of one item, that being Māori housing. She wished to move that a sub committee be set up consisting of Crs. McClintock, Geraghty, the Health Inspector and the mover [Newton] to investigate conditions in connection with this matter, and to report back. Seconded Cr. McClintock and carried.[2]

Agreeing with Newton, the councillors pointed out the oversight and moved to create a sub-committee focused on investigating the burdens Māori faced with regards to housing. According to the Onehunga Council minute books, this was the first instance of Newton officially advancing issues related directly to Māori in the community, but it certainly wasn’t the last.

Thus began a pattern of Newton being a direct liaison between the Council and the Māori community in her two terms in office. Upon receiving an application from Māori women to cultivate Council land rent free, she put forward the case to the Council and gained their majority vote for the motion.[3] Among other things, Newton made a point to push for greater job opportunities for Māori workers, and advocated for One Tree Hill to have its name officially be recognised by Auckland Council as Maungakiekie for the centennial celebration in 1940.[4]

A photo of the Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books of Cr. Newton asking the council if they would consider supporting her pledge for One Tree Hill to be named Maungakiekie for the centennial celebration in 1940. Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books 30th September 1940, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 21, Auckland Council Archives.

In addition to Newton’s political advocating, she also was a great promoter of tikanga Māori in her capacity as secretary of the Epsom-Oak branch of the Labour Party, and as head of the Tamaki Māori Women’s Welfare League. The effect of Newton’s work within the wider Auckland community far exceeds simple entertainment for interested Pākehā. Newton used her social and organisational skills to foster connections between European and Māori culture in Aotearoa New Zealand as well as facilitate political bonds and a working relationship between the two cultural groups.

The events Newton organised often had a political motivation where she brought mātauranga Māori culture into the political realm. This was often done during the welcoming, celebrating and farewelling of prominent members of society and the Labour party. There are reports of Newton curating the ‘fine examples’ of Māori woven crafts at the Māori School of Learning to ‘Her Excellency’ Lady Bledsloe, wife of the Governor General.[5] Newton also organised a Māori farewell for William Jordan M.P. departing as High Commissioner to London in 1936, at a Māori ceremony where 56 girls from the Queen Victoria Māori Girls’ College took part in the send-off.[6] The same year she also welcomed the Prime Minister, Michael Joseph Savage, to the Māori Orakei village by hosting the afternoon tea, taking place before the traditional hāngī.[7] In addition to this, Newton organised presentations of gifts made to prominent Labour Party members, including a Māori style carved book rest and a carved pipe.[8] Despite being virtually unknown today, Newton was involved in the organisation of a multitude of high profile events.

In a grand display of Māori and Polynesian culture, the South Seas concert was put on display in 1936. As one of the organisers, Mere Newton was well settled in company of high esteem, including Princess Te Puea Hērangi and the Anglican Māori Minister for the Auckland district Reverand W. Panapa. The Auckland Star reporter spoke of stirring hakas, poi dancers of rare quality, and Māori chants difficult for the European ear to distinguish and the European voice to reproduce. A powhiri, village games and stories being told of Māori arrival to New Zealand were on the programme to a “large and appreciative audience”.[9]

A Progressive Voice for Medical Fallacies in Society

Where Newton’s political approach was influenced by her culture and her experiences in the Māori community, Dreaver was influenced by her Progressive upbringing and her experiences on the Auckland Hospital Board from 1933 to 1944 which informed her time in parliament. Dreaver was born to a strong trade unionist father and she had worked through the Great Depression as a piano teacher supporting her family.

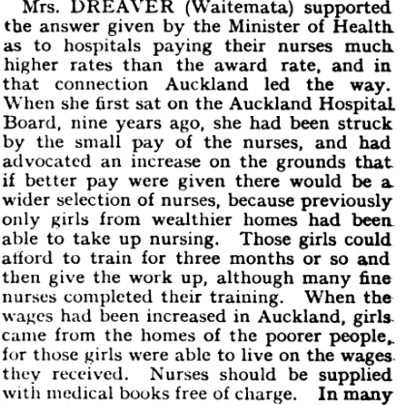

Whilst she commented on diverse issues, strong themes emerge from Dreaver’s speeches which focus on the plight of women and children, especially but not exclusively in a medical sense. Dreaver stressed the importance of the need for a school for obstetricians and gynaecologists in the Auckland district. According to Dreaver, this was to enable doctors to get the training they needed in Auckland instead of having to go abroad for it, citing that it would undoubtedly reduce maternal mortality.[10] She also advocated for better pay for nurses, stating that there should be a wider selection of nurses coming from poorer backgrounds and a pay increase would rectify this issue.[11] She also inquired and raised awareness to the Minister of Health about the urgent need for the supply of insulin after a crisis with distribution in 1942.[12]

An extract from Historical Hansard records detailing Mrs. Dreaver’s support and advocacy for nurses receiving increased pay. Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust, (9th July 1942) Adjournment: Questions, p.530.

Another example of Dreaver’s political campaigning to improve healthcare was her support of the Auckland Community Health Centre and the Auckland Council Empowering Bill, where the aim was to establish a community health service for the City of Auckland. Dreaver claimed when she introduced the Bill to parliament for a second reading that:

“There was nothing political in or about it, and there was no profit making in the objective for which statutory authority was sought. The Bill aimed at a further promotion of the welfare of the poorer people and their children.”[13]

As much as Dreaver and Newton were influenced not only by their gendered experiences, but also by their social and economic circumstances and community connections which impacted on their politics.

This is the third article in a three part series. To read article one.

* Brooke was one of four students awarded a 2020 Summer Scholarship at the University of Auckland out of a highly competitive field. Her award was funded by a Jonathon and Mary Mason Scholarship in Auckland history. Brooke’s research project explored women in Auckland politics. She focused her efforts on two women, studying the motivations, methods and achievements of Mary Dreaver and Mere Newton.

[1] Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books, 28th August 1939, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 20, Auckland Council Archives.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books, 27th September 1939, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 20, Auckland Council Archives.

[4] Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books, Monday 30th March 1942, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 21, Auckland Council Archives, Onehunga Borough Council Minute Books 30th September 1940, OHB 100 Council Minutes 1868 – 1989, Item 21, Auckland Council Archives.

[5] ‘Māori Handicraft’ Auckland Star, Volume LXIII, Issue 165, 14th July 1932.

[6] ‘Māori Farewell’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 170, 20 July 1936.

[7] ‘Visit to Orakei’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 4, 6 January 1936. See Nicolas Jones article…

ncreased pay. dvocacy for nurses recieving etailing Mrs. Dreaver’or ‘he s and a pay increase would rectify this issuealf of the

[8] ‘Gifts from Maoris’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 231, 29th September 1936.

[9] ‘South Seas concert’ Auckland Star, Volume LXVII, Issue 52, 2nd March 1936.

[10] Linda Bryder The rise and fall of the National Women’s Hospital

[11] Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust, (9th July 1942) Adjournment: Questions, p.530.

[12] Historical Hansard, Hathi Trust, (25th June, 1942) Supply of Insulin, p. 399.

[13] Historical Hansard Hathi Trust (8th October 1941) Auckland Community Health Centre and Auckland City Council Empowering Bill, p.1051.