Part One

Parnell: The Patchwork Suburb

Part Two

Parnell: A Suburb of Contrasts

Part Three

Gentrification in Parnell

Part Four

Living in Parnell

Parnell, as one of Auckland’s oldest suburbs, has a history extending back to the early settlement of the area. When Pākeha arrived in New Zealand and began obtaining land, the area which we now call Parnell was one of the earliest acquisitions. Parnell Village, as it was initially called in 1841, was a crucial part of the growing city of Auckland. After Parnell Village was brought under the governance of Auckland City in 1915, however, histories of the area became fewer and the local significance of the suburb was often obscured. The developments of the twentieth century, a period filled with events of international significance, are often overlooked in relation to changes within the local history of Parnell. For these reasons, over the course of my Summer Research Scholarship, I chose to focus on shifts and changes in Parnell after the Second World War.

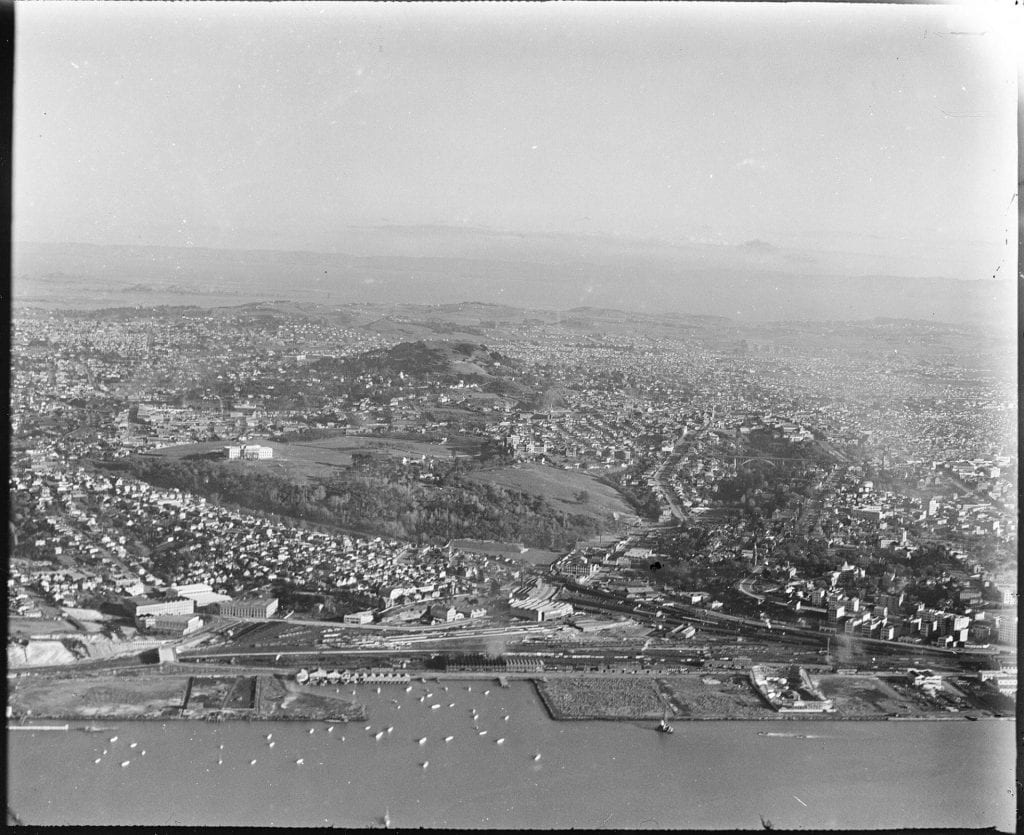

Photo: Central Auckland from the air, 1928, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections FDM-0473-G, Auckland.

Why study local history?

When thinking about local history, there is often a question that jumps to mind: what is the significance? In the twenty-first century, at a time when enrolment in university Arts degrees are faltering and mainstream (historical) entertainment sources such as the ‘History Channel’ are instead dominated by reality TV, studying local history seems like a lost cause. In New Zealand particularly, we can often be dismissive of our history – not out of a disrespect for the past, but instead an apathy. History has an image problem. It comes across as boring, it makes people think they need to memorise dates and locations, and so on. In New Zealand schools, we have often taught our history in very specific ways, which not only reinforces misconceptions about our nation’s history, but creates a relatively boring narrative which saps enthusiasm for further study. It is worth noting that under the Sixth Labour Government, there has been a massive push to revamp what New Zealanders are being taught about our history, with in-depth consultation with Māori and an acknowledgement that New Zealand’s past is filled with diverse stories, rather than a uniform ‘colonial’ narrative.[1] This is a welcomed move, and hopefully it will help remake the image of New Zealand’s history. However, the study of local history may still come across as tedious to some. This is compounded by the fact that for many, history is the study of the distant past and previous lifetimes. In this case, the suburbs and homes of New Zealand are overlooked in favour of famous battles of ‘great civilisations’. Why bother studying the everyday?

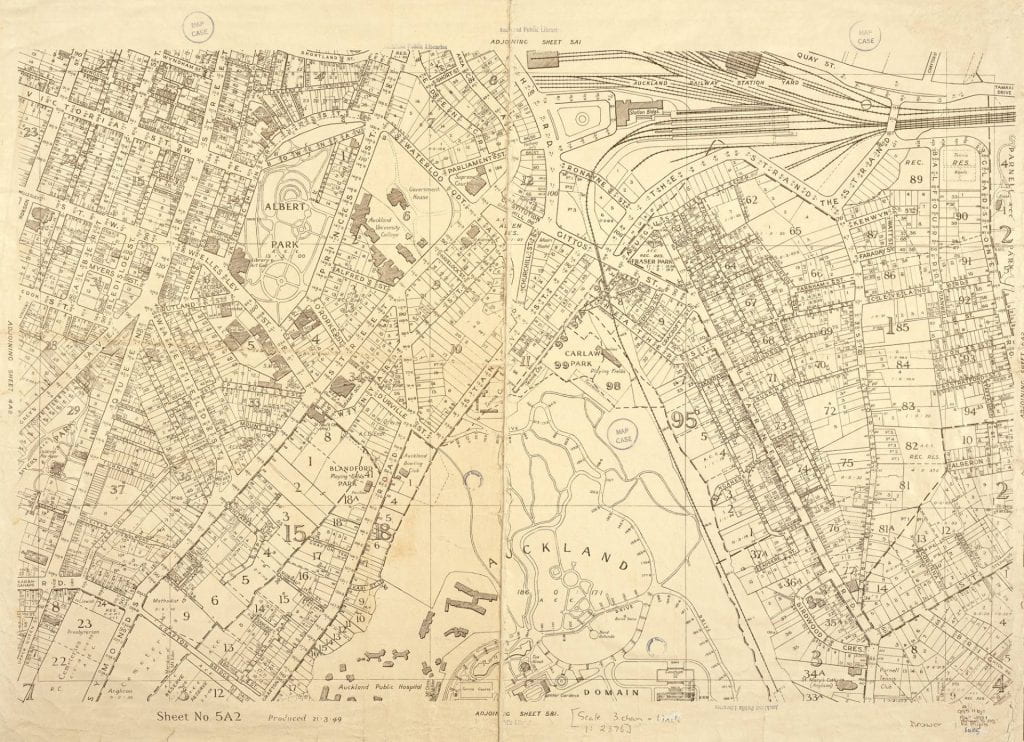

Auckland City Council planning map, sheet No. 5A2, 1949. Many maps like this were produced throughout the twentieth century as Auckland Council developed the city: see what differences you can spot! Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 6005, Auckland.

The answer is relatively simple. If we fail to study our local history, it becomes difficult to formulate any cohesive narrative of the past. In this way, we risk losing our heritage. Local history is just as important as the history of major monuments or landmarks, because it is in the local spaces that we experience the day-to-day, our social and cultural histories. The places where we live and work influence how our lives progress, and if we ignore the history of these areas we can become disconnected from the land around us. As I studied the Auckland suburb of Parnell, I began to feel a greater connection not just to the suburb but to Auckland as a whole. I am not originally an Aucklander, but in studying the city’s history I started to feel more ‘at-home’ than I had previously. This is why local history is important: it grounds us.

Why Parnell?

When beginning the project, there were many different suburbs I could have chosen to study. Why Parnell? I was originally attracted to Parnell’s history because of the suburb’s reputation. In the Auckland of 2020, Parnell is often associated with images of wealth and respectability. For nearly two decades, Parnell (as part of the Epsom electorate) has voted consistently for representatives from the National and ACT Parties, which continues to colour how the suburb is perceived. On a more personal front, I was drawn to Parnell due to my own experiences in the area. Over the course of my studies, I have often found myself in Parnell for work or visiting friends and family. It was at the beginning of last year that I started spending much more time in the area, visiting friends who had just moved to Auckland for work. It was when I visited this flat, located on Garfield Street, that Parnell’s unknown history started to jump out at me. Here was an 8-bedroom flat, 3 stories tall, in one of Auckland’s oldest suburbs, being rented to people who were just starting out in the workforce. Rent was (relatively) expensive for a house which had a number of peculiarities: bedrooms led in to other bedrooms, the stairs were incredibly narrow, and the backyard almost non-existent. This was not a home designed as an 8-bedroom flat, but instead intended as a magnificent villa. This trend played out all along the street, with multiple homes converted into flats or medium-density living. Looking up towards Parnell Road, and down towards St Georges Bay Road, these older homes give way to modern businesses and industrial developments. The whole area is a patchwork.

Photo: Hulme Court, one of Parnell’s most distinctive historic buildings, in 1977. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 435-17-01, Auckland.

Photo: Hulme Court, one of Parnell’s most distinctive historic buildings, in 1977. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 435-17-01, Auckland.

As I delved into the story of Parnell, this same trend I observed was reflected in the suburb’s history. Throughout the twentieth century, Parnell has found itself to be a ‘patchwork suburb’. It does not quite fit into one easy category as do some other parts of Auckland. It has attracted workers, students, young families, the elderly, and international migrants, while also pushing these very same groups out at various points in the twentieth century. The gentrification of the 1960s and 1970s, which helped turn the old slums into up-and-coming developments has perhaps extended the life of the suburb significantly. Writing about Parnell, I relied on the oral histories gathered by the Parnell Heritage Society and the Auckland Central Library. Planning maps and old photos could only tell me part of the story. In order to truly understand Parnell’s history, I needed to hear from the people who had lived there. The stories I have listened to do not present the full history of the suburb but they do provide first-hand accounts of how changes were experienced. There will be those of you reading who feel I may have done Parnell injustice; you may remember it differently from those who have had their oral histories documented. To you, I urge that you also record your stories. Write them down, audio-record them, and get in touch with your local heritage groups. Without these sources, the history will be lost to time.

[1] Jessica Long, ‘New Zealand History to Be Taught in Schools by 2022, says PM Jacinda Ardern’: www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/115712569/new-zealand-history-to-be-taught-in-schools-by-2022-says-pm-jacinda-ardern?rm=a