Part Four

Activism at the Summit: a new beginning for Maungakiekie?

by Isabella Wensley*

The Summit complex on Maungakiekie/One Tree Hill has a complicated symbolism. The monument and summit itself have been seen alternatively as a memorial to John Logan Campbell, a symbol of racial harmony, or a symbol of colonialist domination.

This complicated web of interpretations simmered below the surface throughout the twentieth century as the city of Auckland sprawled around the mountain. The tree and obelisk became a symbol of Auckland, for visitors and locals alike. The original debate over what the summit stood for was brushed over by the creation of its icon status, becoming something in itself, separate from the racial and colonial meanings.

This was not to last. While throughout the 1990s the summit was supposedly still standing as a monument representing unity for the city, disputes over Treaty of Waitangi settlements and Māori sovereignty, coupled with pervading social and economic inequities for Māori, were sowing resentment under the surface.

This was all brought to a head on October 26, 1994, when Māori activist Mike Smith took to the lone pine tree at the summit of Maungakiekie in the early hours of the morning. In possibly one of the most well-known acts of protest in New Zealand he sawed through a chunk of the tree, before being arrested by police.

While the tree remained standing after this attack, its lifespan was significantly shortened, and it embarked on a dangerous lean. A steel frame was added to protect the tree from future attacks, further adding to the complicated web of structures on the summit. However, this structure did not protect the tree as intended and on October 5th, 2000, Smith’s family members returned to finish the job. Reported as “praying in Māori” they drove a wedge through the chainsaw marks, severely damaging the sick tree.[1]

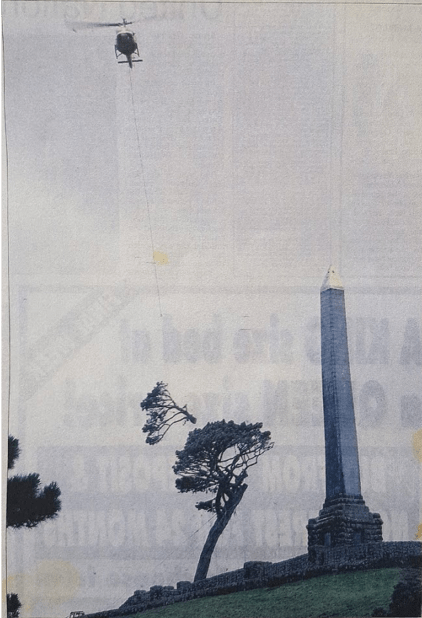

This final attack marked the death knell for the tree. On the 26th of October that same year, Auckland Council approved its removal and it was taken away limb by limb by helicopter in front of crowds of emotional Aucklanders.

The tree is removed by helicopter in front of a crowd of emotional Aucklanders. “City pines for an heir,” Central Leader, October 27, 2000.

The outpouring of grief at the removal of the tree surprised many and asserts the idea of Maungakiekie as a symbol of identity for Aucklanders. At the removal, the mayor Christine Fletcher stated, “Aucklanders are sentimental about the tree, and it is considered by the entire country as an icon.”[2] Nothing makes this clearer than the media coverage of the removal. The removal was treated as though it was the death of a person. Reports from the day before talked of a ‘funeral’ being held for the tree with people wrapped in rugs sitting vigil by the tree until dawn and many laying wreaths and singing.[3] At the scene of the removal, people stood with tissues and hankies for their tears. There was also a rush to collect pine cones and leaves as souvenirs to remember the tree by.[4] In the days following, many walked up to the summit to lay flowers on the stump that one reporter emotively stated was “still oozing sap 24 hours later.”[5] An obituary for the tree was put in the Herald stating its “death date” on October 26th aged 125 years old.[6]

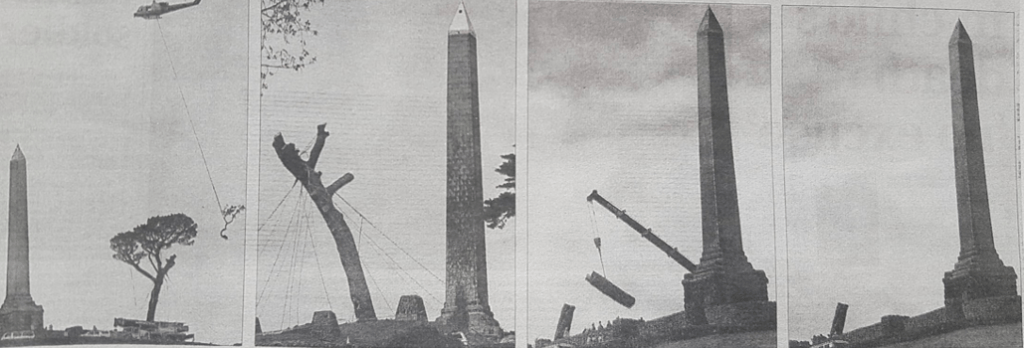

A series of photos depicting the felling of the tree. “125 years of city history felled,” The New Zealand Herald, October 26, 2000.

Many Aucklanders responded angrily to the chopping down of the tree. For example, one letter to the herald lamented the fact that the tree could not have one final use as quote, “Mike Smith should have been hanged from it”.[7] The ACT party drew links between Smith’s actions and a threat to state legitimacy, implying that it and the opening of a floodgate in Māori protest against Treaty of Waitangi settlements.[8] Today, of the local histories which do include a section on the attack, the act is labelled as “dissident vandalism”.[9]

Māori were divided in their response to the attacks. Some, for example, Sir Hugh Kawharu respected the message of the protest but not the method, in reference to the fact that Smith attacked the sacred Maungakiekie instead of making a political statement at Orakei.[10] This was also reflected in the response of Ngāti Whātua who viewed Smith as a trespasser going against the wishes of their ancestors who had authorized the planting of the tree and the erection of the obelisk. However, at the same time, Ngāti Whātua launched a Treaty of Waitangi claim that the sale of Maungakiekie was invalid given its sacredness to Māori at the time. This suggests again that while critical of the method of protest, Ngati Whatua leaders did not necessarily oppose the message.

Over time, opinions on the protest are less divided. Once the high emotions had simmered down, reflections could be made on the tree and what it symbolized. For many, the highly publicized act of protest was a catalyst for learning more about Māori treaty grievances, bringing a greater understanding of the issues with post-colonial legacies. When periodically the event returns to the media, the point is made that Smith’s actions were an “undeniable success” if his aim was to provoke debate, given that we are still talking about it today.[11]

In 2016, the Auckland Council announced that they would plant new trees at the summit. Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei had postponed any idea of replanting while their Treaty claim was being processed. After treaty negotiations were completed in 2014, discussion could return to replanting the tihi of Maungakiekie. When the tree was first removed in 2000 there was a substantial debate about the replacement. Some favoured another English pine tree to “symbolise the early settlers who created this great country.”[12] Others proposed new ideas such as a “flowering cherry tree”, a “steel sculpture” or two trees; a pine and a totara to “symbolise the spirit of the treaty.”[13] Overwhelmingly though there was consensus that it could not remain as ‘no tree hill’. No matter what was planted, the tree had to be replaced. The Tāmaki Authority eventually decided to plant a grove of 9 pohutukawa and totara trees. This departure from the Monterey pine is significant as it represents an embracing of the Māori history of the summit where, before it was cut down in 1852 totara had stood for years, planted over the whenua of a local chief.

Crowds gather to see Historic One Tree Hill planting,” New Zealand Herald, June 11, 2016.

It is tempting to draw the connection that with this new planting, a new, more united generation can begin for Auckland. Indeed, this is what then-mayor Len Brown envisaged with his statement that the trees were a symbol of a more “united city” that, “against the backdrop of the resolution of most of the iwi grievances” has moved past previous divisions.[14] However, it is not that simple. The conflicting identities present at the summit of Maungakiekie did not disappear with the planting. These identities have much deeper roots.

However, it cannot be ignored that the summit and Maungakiekie have changed significantly to depart from its colonial symbolism. While the obelisk still stands, the mountain itself, under the 2014 Tāmaki Collective Treaty Settlement, is vested in the group of Auckland iwi and hapū called the Tāmaki Collective that, alongside Auckland Council, jointly manages the mountain.

Today, Maungakiekie officially has a dual Māori/English name, is vested in Māori authority, and has native New Zealand trees at the summit where a pine tree once stood. It has still retained its icon status for Aucklanders but with a new understanding and acknowledgement of New Zealand history since colonisation.

[1]“Man Arrested at Pine on One Tree Hill,” The Dominion, October 6, 2000.

[2]“One Tree Hill Felling to Begin Tomorrow,” New Zealand Herald, October 25, 2000.

[3]“Funeral for a Friend of the City,” The New Zealand Herald, October 26, 2000.

[4]“Crowd Grabs One Tree Hill Souvenirs,” The New Zealand Herald, October 26, 2000.

[5]“Skyline Misses its Signature,” The New Zealand Herald, October 28, 2000.

[6]“Obituary: A Lone Pine,” The New Zealand Herald, October 28, 2000.

[7]“Replacing the Tree: What readers think,” New Zealand Herald, October 27, 2000.

[8]Leonard Bell, “Auckland’s Centerpiece: Unsettled Identities, Unstable Monuments,” p.115.

[9]Graham W.A. Bush, The History of Epsom, Auckland, 2007, p.385.

[10]Bell, p.70.

[11]“The Maungakiekie movie: sometimes it takes a chainsaw to start a conversation,” The Spinoff, August 4, 2017.

[12]“Replacing the Tree: What readers think,” New Zealand Herald, October 27, 2000.

[13]“Replacing the Tree: What readers think” New Zealand Herald, October 27, 2000.

[14]“Activist: One Tree Hill Part of ‘Political Illusion,” New Zealand Herald, October 20, 2015.