Part One

“Mere Cold Stone” The Different Meanings of the One Tree Hill Obelisk

by Isabella Wensley*

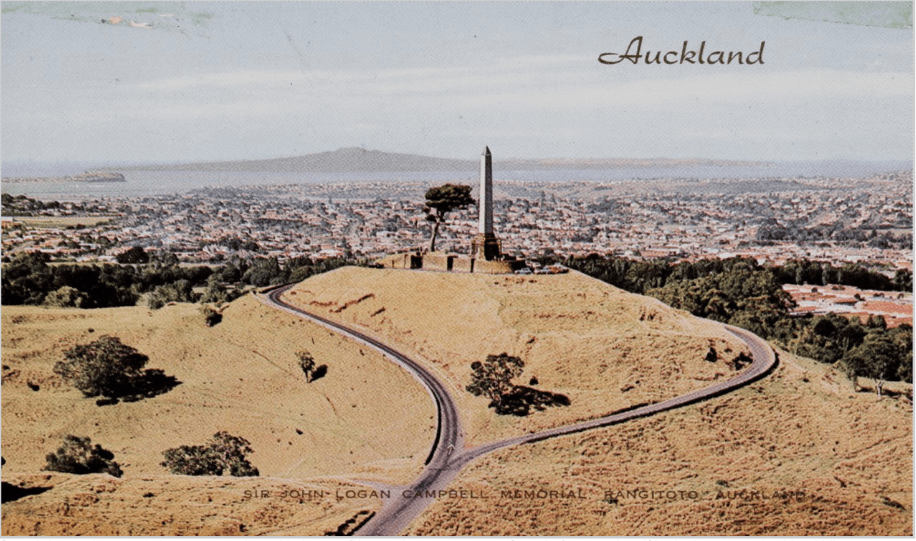

Photo depicting the completed obelisk at the summit of Maungakiekie. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 996-159.

The Maungakiekie/One Tree Hill obelisk is one of the most distinctive landmarks in Auckland. Standing at odds with its natural landscape, it rises 100ft above the summit, its sharp concrete angles contrasting with the rolling grassy hilltop it sits upon. Viewed close, a sharply etched inscription on two faces is visible. It reads:

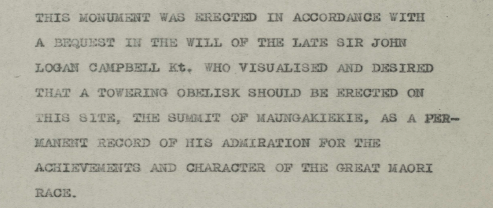

“This monument was erected in accordance with the will of the late Sir John Logan Campbell who visualised and desired that a towering obelisk should be erected on this site, the summit of Maungakiekie as a permanent record of his admiration for the achievements and character of the great Maori people.”

Despite construction finishing in 1940, the One Tree Hill obelisk was only unveiled at a ceremony in 1948. The delay was agreed to after the Cornwall Park Trust Board received a petition from the Akarana Māori Association to postpone the ceremony due to the wartime conditions.[1] The Māori King was invited to lead the ceremony.[2] The arrival of the obelisk was met with much less fanfare than was initially planned, only being mentioned briefly in the newspapers, with the delay seeming to quash the initial excitement caused by the obelisk.

Nonetheless, the obelisk is now a clear symbol standing above Auckland. It is meaningful to so many, referred to as a “landmark that spelt home to Aucklanders” and “Auckland’s icon”.[3] But though most agree that the summit is meaningful for Auckland, there is less agreement about what it is symbolic of.

This debate around the meaning of the obelisk can be boiled down to three main perspectives. Firstly, there is the misconception that the obelisk stands as a memorial to Sir John Logan Campbell. Secondly, linked in with the memorial idea, is the notion that the obelisk is representative of colonialist dominance over the landscape. Finally, the obelisk can be seen as a symbol of racial harmony and respect.

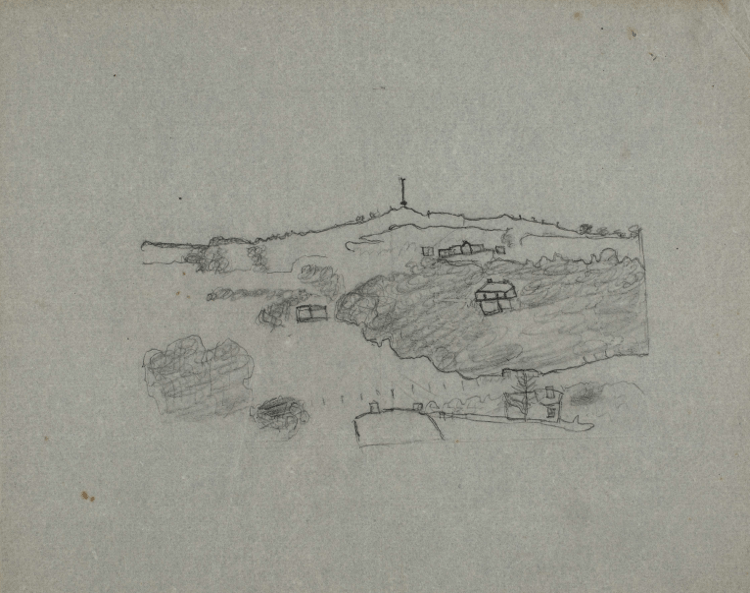

View of the obelisk from the foot of Maungakiekie. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints, 02486.

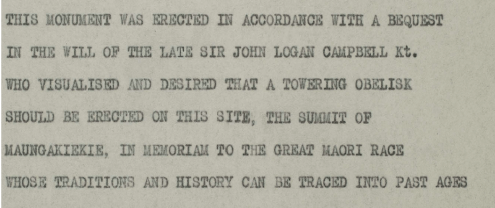

The trustees of the Board began with a clear vision. Sir John Logan Campbell bequeathed £5,000 for the “uprearing heavenward of a towering obelisk in memoriam to the great Maori race.”[4] He intended the obelisk to represent his respect and admiration for Māori at a time when he believed they were a people “doomed in our own day”.[5] The words “in memoriam” in particular drew attention to his belief in the eventual coming of “a never-ending night to the aboriginal race of darker blood”.[6]

Sketch of Maungakiekie with proposed obelisk. Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-5-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

Early building plans for the obelisk demonstrate the clear intention to assert this notion of the ‘end of the Māori race’. For example, early plans of the obelisk included a statue of a Māori chief throwing away his “old-time weapons” to grasp the “opportunities for a fuller life made possible by the advent of civilisation”.[7] Linked in with this was the colonial confidence that the obelisk would “typify the new outlook that has come to the Maori race with the advent of civilisation”, the clear inference here being that colonisation was beneficial to Māori.[8]

Despite this strong vision with which to work from, throughout the 1920s and 30s, the Board faced significant obstructions in getting the obelisk started. Due to a series of funding problems, engineering roadblocks, and changing social attitudes, the Board gradually faced greater opposition to the monument.

Firstly, the Board received countless suggestions to replace the obelisk with something more appropriate for the landscape than the proposed Egyptian obelisk. Suggestions to make it into an observatory were advanced by the Auckland Astronomical Society and were subsequently rejected by the Board.[9] The announcement in 1934 that the costs of building the obelisk had raised to £15,000 increased criticism. Several letters referenced the perceived uselessness of a memorial, with one stating “£15,000 on mere cold stone is too much and I hope the proposal will be revised.”[10]

Secondly, opposition was mounted against the very idea the memorial was proposed to stand for. For example, a letter in 1933 raised the issue that “the words ‘in memoriam’ may possibly be read as implying that the history of the Maori Race is finished” noting that “we are all glad to think that there is to-day a very different view of the future of the Maori”.[11] Similarly, another letter expressed concern that the money should be spent on improving the future for Māori, instead of relegating them to the past.[12]

By the time the monument was erected, the board adjusted the inscription to remove any reference to the idea of a need to memorialise a dying race as Campbell had envisaged. Therefore, Auckland ended up with a monument to “the great Maori people”, a much more future-focused inscription than the original.

Proposed inscription for the obelisk with the controversial “in memoriam” replaced with the words “record of admiration”. Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-314-2-8-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

One proposed inscription for the obelisk. Note in particular the words “in memoriam”. Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-314-2-8-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

This description of the Board’s decision-making process in construction suggests that Māori had no agency in the decision. This is untrue. There was collaboration between Auckland and Northland iwi on the design and purpose of the obelisk. The need for Māori consultation was first raised in August 1933 in a letter that asked the question, “Have the Maoris themselves been consulted as to their wishes about the memorial?”[13] This letter was intended to raise opposition to the obelisk, with the writer supposedly thinking that any consultation would result in a change of plans.

However, Māori consultation heralded significant support for the memorial. In January 1937 a petition was presented to the Board by the Akarana Māori Association with signatures from Waikato and Auckland iwi leaders as “evidence of the unanimity of the Māori people” as to the suitability of the memorial.[14] Later communication expressed a desire for Māori to be involved in the design process with this wish being fulfilled through several summit meetings and the appointment of an artist who had Māori support.[15] Where the board had previously been criticised for the “uselessness” of an obelisk, Māori opposed the memorial having any “utilitarian purposes” in order to show appropriate respect to the sacred “memory of our ancestry”.[16] Additionally, upon finalisation of the plans, the Association wrote of the gratitude they felt that “the historic past of our Maori Race” should be honoured.[17] Here there is no mention of the idea that the obelisk was a memorial to a ‘dying race’ suggesting already vastly different ideas of what the obelisk meant.

Returning to the initial question of what the obelisk stands for, it appears that the answer is complicated. There are many varied perspectives for what this distinctive monument is memorialising and what it represents for Aucklanders.

For Māori at the time, the obelisk was reportedly seen as a way to “urge to us Pakeha and Maori now a united people to carry on to future time the noblest ideals of our respective ancestors”.[18] However, for many others, the obelisk was seen as a symbol of colonisation and settler dominance. For example, the summit of Maungakiekie is often confused as a memorial to Sir John Logan Campbell himself. This confusion began early as evidenced by the swift rebuttal “the monument is not in any sense a monument to Sir John Logan Campbell”, by the Board in response to a contractor labelling it as such.[19] Despite this quick shutdown, confusion has remained that the obelisk stands as a memorial to Sir John Logan Campbell. It is easy to see where this confusion originates. At his death in 1912, John Logan Campbell requested to be buried not in Parnell with his daughter but at the summit of Maungakiekie.[20] His grave position, at the base of the obelisk, therefore, is somewhat misleading and can be seen as dominating the summit memorial.

The obelisk, therefore, cannot be described simply as a symbol of one idea or concept. It is inherently a complicated monument that can communicate many different messages. Dictating exactly what message it is intended to communicate would always be quashing the voice of another. What is indisputable, however, is that the obelisk is an Auckland icon.

[1]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-314-2-24-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[2]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-317-1-4-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[3]“More than a Tree,” Central Leader, October 25, 2002. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

[4]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-313-1-9-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[5]Sir John Logan Campbell, Poenamo Revisited: A Facsimile of the 1898 Edition of Poenamo By Sir John Logan Campbell, p.86.

[6]Campbell, p.86.

[7]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-311-3-7-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[8]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-311-3-8-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[9]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-313-1-23-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira.

Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[10]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-7-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira.

Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[11]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-313-6-4, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[12]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-313-1-17-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[13]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-311-4-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[14]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-6-3-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[15]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-313-2-5-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[16]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-7-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira, Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[17]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-6-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[18]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-312-7-1-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira.

Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[19]Sir John Logan Campbell Papers, MS-51-314-1-2-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tamaki Paenga Hira. Deposited by Cornwall Park Trust Board (Inc).

[20]Lucy Mackintosh, “Shifting Grounds: History, Memory and Materiality in Auckland Landscapes c.1350–2018,” p.200.