Part One

Bridging the East and West: the First International Students in Auckland

by Laura Prahash*

Many of us, myself included, tend to take the presence of international students for granted. With this pandemic preventing many international students from staying in or entering Auckland, it’s become increasingly clear how valuable their participation on campus and in our society is. For example, the current absence of international students has influenced hiring policies within the University of Auckland, there are far less students on campus, and many shops around the city campus that serviced this student community have had to close.[1]

But nothing is ever completely unprecedented in history. COVID-19’s impact on international students as discursive subjects can be traced back to the dynamic relationship Auckland has always had as a city with these transient residents. These recent developments and my own personal history as an immigrant sparked my interest in the history of international students in Auckland City.[2] My early research led me to the first international students at the University of Auckland who came in the 1950s as part of the Colombo Plan, a foreign aid scheme. It was reported at the time that these students were grateful to receive training and participate in a new way of life. They initiated and engaged in instances of cross-cultural interactions, which were facilitated by the campus clubs and the media, and helped to introduce greater diversity into a previously insular campus and Auckland community.

The Colombo Plan was intended to not just be altruistic aid, but to act as a “weapon against communism.”[3] It was hoped that aiding South and South-East Asia would prevent the spread of communism through those regions to our shores. Following China’s turn to communism, there was uncertainty over how the now “Red China’ would affect international relations and the distribution of power.[4] Foreign Defence Ministers from Commonwealth countries met together in Colombo, Sri Lanka, to discuss the threat that China now posed, and how to support surrounding Asian countries during this period. The New Zealand Minister of External Affairs, Mr Doidge, was one of many who viewed world peace as an important international policy and saw the Colombo conference as an opportunity to work toward it.[5]

The Colombo Plan consisted of two types of assistance: capital and technical. The former involved New Zealand sending people and capital overseas to set up institutions and resources, such as building clinics in Ceylon or sending surveyors to Malaya, while the latter consisted of students being sent here from participating countries to be trained.[6] The Colombo Plan was just one of several assistance programmes that the New Zealand government offered international students.

The first group of Colombo scholars arrived in New Zealand in March 1951, with many more arriving soon after. They were generally in their early to mid-twenties; many of them already had education and jobs, but were here to obtain further qualifications or more specialised training. The courses they undertook varied in length from a few months to several years.

The subjects they pursued – engineering, teaching, accounting, agriculture – were all approved with the intent that students would learn the content here and then return home with their newfound knowledge to help their home country.

As foreign policy personified, the Colombo Plan students received a lot of press coverage. Seeing these students walk through our Auckland streets helped to bring the aid work that New Zealand was doing overseas closer to home.[7] There was even a documentary made about the students that detailed some of the study and work that the students engaged in.[8]

As a student in the video said,

“Being granted our degrees or diplomas, we can now go home where we must face a new challenge. We must leave many friends behind, and we hope also something else: understanding and our appreciation. We hope that we have given something to New Zealand, and not just taken, because the Colombo Plan is for the mutual benefit of all of us. We leave, and others are already arriving to carry on the good work, and they too will return, and together, we will work for the benefit of our countries.”[9]

Obtaining a qualification here was not just about individual achievement, but for the good of their nation.

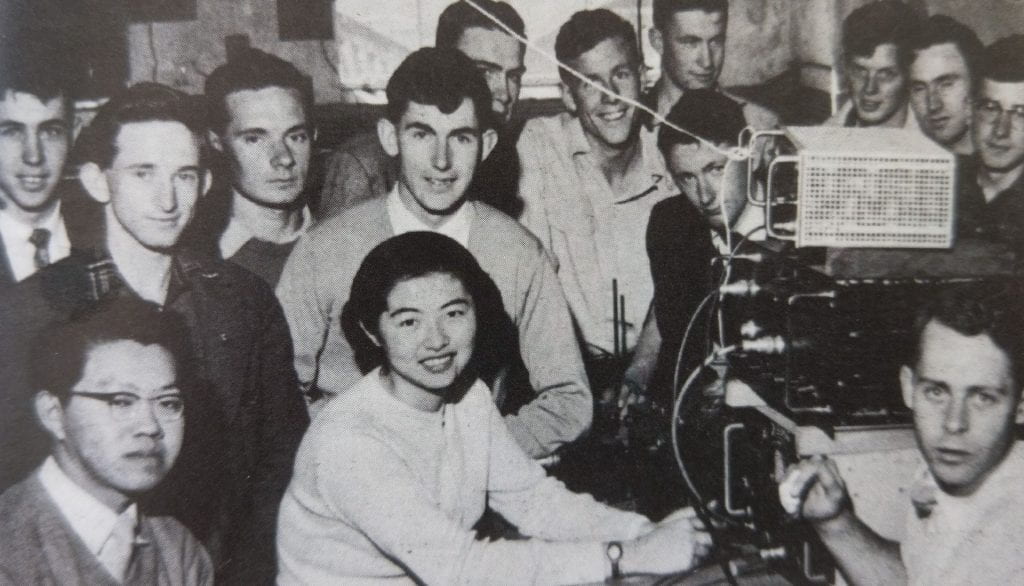

A photo of Malayan student Teh Paik Lian in her Physics class[10]

The Colombo scholars in Auckland generally excelled academically. Some even went on to win prizes, such as Peter Yew, who won the Auckland University College prize for Accountancy in 1952, or Goh Kuan Meng, who won the Stage 1 Botany Prize in 1957.[11] Two Colombo Scholars even worked at the University library in 1959 after the Cataloguer and her assistant resigned.[12]

But what about outside of the classroom? Like most overseas students, the Colombo Plan students came here, “not only to study from books, but also to see life here.”[13] They visited marae, met local students and families, and saw tourist destinations. But beyond improving racial understanding and cultural exchange between local and international students, this also aided relationships between international students from different countries as these students formed bonds with others from neighbouring countries they otherwise would not have met. They were united in their identity as Colombo Plan students but still retained a cultural identity that was uniquely theirs, and they shared it with each other through song, dance, and spending time together.

Outside of these gatherings, the Colombo Plan students in Auckland were involved in campus clubs, which influenced their experience of Auckland, and how Auckland understood these students in turn.

A prominent group on campus which many international students joined was Students’ International (SI), founded by a mix of international and local students in September 1958. Another group was the Auckland Malayan Students Union (MSU). 50 members of the MSU, mostly Colombo Plan students, organised a celebration on 31 August 1957, to mark the Independence of the Federation of Malaya. The new national anthem was played but no one sang the words because the government hadn’t yet sent them the lyrics, and the students themselves only received the tune that morning.[14] At the event, a local MP and the MSU Chair both expressed the benefits of an education abroad, and stated that a new Western perspective and greater cultural awareness was gained alongside a qualification.[15]

The two groups took different approaches in their interactions with Aucklanders. SI sought to establish interpersonal relationships between domestic and international students, while MSU chose instead to interact with the wider public as a group to encourage interest in Malayan culture. Despite the different approaches, SI and the MSU would work together to organise a Malayan Evening in 1958.[16]

As players in a game of cultural exchange, the students were clearly thinking about their interactions with the locals, both students and the wider public, and about how the clubs could help to facilitate and encourage a broader range of relationships. The Colombo Plan may have been touted as a bridge between ‘the East and the West’, with the governments as architects, but it was the clubs and the media who formed planks across the foundations of policy, so that the students could walk freely between.

In later years, SI began to host more cultural evenings and performances. In fact, it was the big concert that SI hosted every couple of years during the 1960s that enabled them to expand their influence from just an on-campus group, to the greater Auckland public. This exposed a predominantly Pākehā Auckland to cultures that they would have had little prior exposure to, especially given the immigration laws of that time. “Gaudeamus” was one such concert organised by SI in July 1961. It was hosted in part to mark the 10th year anniversary of the Colombo Plan, to “show in some tangible way their gratitude for the help which has been given to their countries.”[17] It was very well received, with an opening night audience of around 500 attendees.[18]

Photos from Gaudeamus, July 1961[19]

Other events around Auckland (and New Zealand) were hosted to mark the 10th anniversary of the Colombo Plan. The Auckland Mayor, Dove-Myer Robinson, marked the occasion by hosting a morning tea for about 35 Colombo Plan students.

Three Colombo Plan students at the morning tea marking the Colombo Plan’s 10th Anniversary[20]

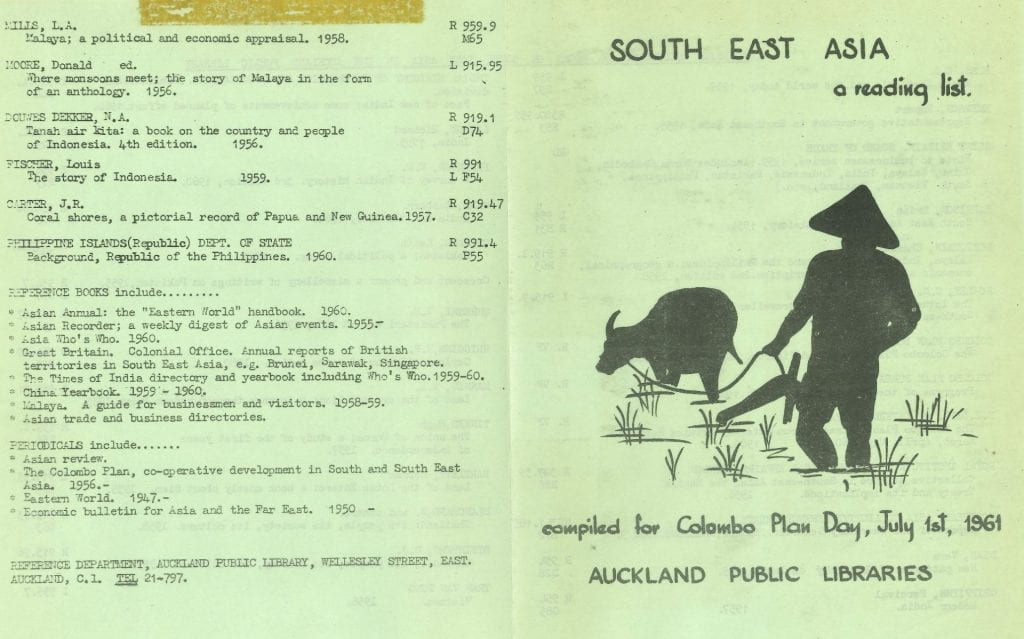

The photo exhibition hosted by the Auckland Central Library was another way for the public to get involved with the anniversary celebrations. There were also dolls, dress fabrics, and carvings on display for the public to look at.[21] Below is a photo of a catalogue that accompanied this exhibit, of which several entries are still accessible today in the same library, 60 years on.

Photos of a reading list pamphlet distributed at the photographic exhibition at the Auckland City Central Library, 1 July 1961.[22]

Not all were in favour of the Colombo Plan, or even the influx of international students. Many students faced racial discrimination or hostility when trying to find board.[23] One letter to the New Zealand Herald denounced the Colombo Plan as a waste of time, claiming that, “there does not appear to be the slightest evidence that we have gained any good will from these people.” An Auckland Colombo Plan student wrote back refuting this, stating that not all rewards were immediately evident or physical, and that this plan was leaving many individuals and countries indebted to New Zealand.[24] He wasn’t the only Colombo Plan student to write to the paper. A student from North Borneo wrote a letter to the Herald expressing his gratitude and the regret he felt at having to leave this “wonderful country and its most wonderful people.”[25]

At the start of the 1960s, the international student community in Auckland could hardly be considered a threat. Although their time here was underpinned by foreign policy and building bridges between New Zealand and Asia, they were also welcomed as a force to expand the insular nature of the Auckland community, facilitating cultural exchange and greater diversity. But that would soon change as their numbers continued to increase along with their voices. Anxiety was already growing around students overstaying and fast-tracking their way to permanent residency, fears we will see amplified by the Minister of Immigration and members of the public in the 1970s.[26] However, this would be met with opposition. The international student body would soon rise as a political force, one which demanded addressing.

[1]‘Dozens of empty stores on ‘golden mile’’, Central Leader, 1 October 2020.

[2]As a South-East Asian migrant, I felt like there had been a lack of work done into the history of South-East Asian migration to Auckland, despite there being a significant SEA population there.. I was stunned to learn that many of the first migrants from this part of the world came to Auckland as international students, and this led me into a path untangling the history of international students here in Auckland.

[3]‘Colombo Plan is Weapon Against Communism’, Auckland Star, 17 July 1952.

[4]‘The Near North II – N.Z. must keep an eye on what is going on’, Auckland Star, 19 January 1950.

[5]‘Mr Doidge’s Policy at Colombo is to Strengthen Empire’, Auckland Star, 5 January 1950.

[6]‘Aid Plan Forges Asian Links’, New Zealand Herald, 1 July 1961.

[7]New Zealand and Colombo Plan’, New Zealand Herald, 7 April 1952.

[8]New Zealand National Film Unit. Pictorial Parade No. 153 (1964), 2015. From Youtube, Video, 16:59. Posted by Archives New Zealand.

[9]Pictorial Parade No. 153.

[10]Fay E. Hercock, A Democratic Minority: A Centennial History of the Auckland University Students’ Association, Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press with the Auckland University Students’ Association, 1994, 67. Photo originally from the Herald.

[11]‘Accountancy Prize – Colombo Plan Student From Borneo’, New Zealand Herald, 1 April 1953; ‘Brilliant Student From Malaya’, New Zealand Herald, 16 October 1958.

[12]Olive A. Johnson, The True University: A Short History of the University of Auckland Library, 1883-1986, Auckland, N.Z: Auckland University Library, 1988, 18.

[13]Pictorial Parade No. 153.

[14]‘East-West Fusion “Will Create a New Nation”’, Auckland Star, 2 September 1957.

[15]‘East-West Fusion “Will Create a New Nation”’; ‘Malayans Mark Independence’, New Zealand Herald, 2 September 1957.

[16]‘Students International Crosses Crevasses’, Craccum, 26, no.2 (1961), 7.

[17]‘Colombo Plan Display’, Auckland Star, 1 July 1961; ‘Colombo Plan students are of high standard’, Auckland Star, 19 July 1961.

[18]‘Races mingle in song and dance’, Auckland Star, 5 July 1961.

[19]‘Students Re-Create Some Festivals and Customs of Their Own Land’, New Zealand Herald, 5 July 1961.

[20]‘Colombo Plan: Way to Win Asians’ Friendship’, New Zealand Herald, 4 July 1961.

[21]‘Colombo Plan Display’, Auckland Star, 1 July 1961.

[22]Library Scrapbook, 1957-1964. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 173.

[23]‘Many Difficulties in N.Z. For Asian Students’, University of Auckland clipping books, 1959-62, MSS & Archives E-3, Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[24]‘Dominion’s Role in Colombo Plan – Borneo Student Gives Opinion’, New Zealand Herald, 1 July 1957.

[25]‘Thanks From Borneo Student’, New Zealand Herald, 8 December 1955.

[26]‘Students From Overseas’, New Zealand Herald, 9 August 1957.