Part Three

Majulah! – The Continued Fight of the Malaysian International Students

by Laura Prahash*

The year is 1979. Malaysian students in Auckland and across New Zealand had just spent the last three years battling a discriminatory quota limiting the number of incoming Malaysian international students, bolstered by allegations of ‘marriages of conveniences’. Little did these students know that the fight was far from over. In May, the announcement of a 750% fee hike for international students would cause an uproar across the country. Here in Auckland, our student associations and leaders stepped up to take the lead in defending what they saw as an unfairly targeted audience.

A 750% Increase

The Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, announced in May 1979 that the fee for private overseas students was to be increased to $1500, marking the shift from “education-as-aid to education-as-trade”.[1] This fee hike was expected to bring in $800,000 revenue by the first year, and $2 million by 1982.[2] Muldoon originally justified the fee hike by insisting that all Malaysian students had rich families who could afford the raised fees, meaning this policy would increase revenue without decreasing the number of students.[3] Despite this policy applying to all international students, Muldoon made it clear that Malaysian students were the target here, and not just because they dominated the international student body. I examined why Malaysian students were targeted specifically, in my previous article.

Early Warning Signs

The cutback and fee hike may have come as a surprise to the students (and to me), but after further research, I realised there were several warning signs years earlier. Annual reports from the University Grants Committee and the Universities from 1969 already pushed for policy regarding international students to be reviewed. The University of Auckland was specifically told by the aforementioned committee to control enrolments due to the limited size of the campus, and began to tighten its general intake policy in 1971. While this included accepting fewer overseas students, it apparently did not go far enough.[4][5]

The overwhelming number of private international students was clearly on the minds of immigration policymakers. When an immigration policy review took place in late 1973, the first topic was private overseas students, as they allegedly cost $3.5m a year more than the fees paid* (* – they acknowledged that this figure was unpublished).[6]

Why were so many policymakers eager to cut down the number of international students? At this time, international students were partially supported by the government (and therefore taxpayer money) and appeared not to contribute to society. The incoming Asian students were also seen as a ‘threat’: studying was a potential route to permanent residency during a time when immigration laws made it extremely difficult for non-Europeans to become residents, hence the former Minister of Immigration’s unfounded claims of “marriages of conveniences”.

Majulah! (Onward!)[7]

The Auckland Malaysian-Singaporean Students Association (AMSSA) once again stepped up and took action. Along with the National Overseas Students Action Committee (NOSAC) and other committees around New Zealand, they organised a Day of Action on June 15th, 1979.[8] When Deputy Prime Minister Brian Talboys showed up on the University of Auckland campus that day to open a new department, he was met with protestors who waved signs and tried to hand him a petition.[9] Students also took to Queen Street, protesting the increase in fees.[10] This Malaysian student described their experience in the protest:

“As we marched down Queen Street I was moved to see its immediate result apart from the large turn-out. The people walking along Queen Street stopped to look at the placards and banners. Those with cameras took candid shots. T.V. crews were filming the event for their news item while radio reporters taped down the students’ reactions.”[11]

Prominent figures on Auckland’s campus were also involved in this issue. Brain Lythe, the Overseas Students Counsellor, explained that many students and their families were already “scrimping and saving”.

Brain Lythe (second from left) on the UOA quad with several bilateral aid students.[12]

Lythe had previously worked alongside AMSSA regarding both the quota issue as well as when international students were banned from participating in graduation ceremonies the year prior, in 1978. He noted that these decisions emphasised “just how vulnerable overseas students are to the whims of decision making which is remote from them and which has little knowledge of the students personally.”[13] The Auckland University Students Association (AUSA) President, Janet Roth, urged all students to get involved, insisting that this was part of a wider attack against education, and that the most vulnerable student population, the international students, were just being targeted first.[14]

Roth was right. If you read newspaper articles in the following few years, you will read about the bursary (allowances for students) being slashed, quotas being enforced, a drop in the number of staff, and increasing fees for domestic students. Just like AMSSA did here, the students would rise up to protest these changes as well.

AMSSA engaged with the press to clear up public misconceptions, clarifying that the majority of students from Malaysia studying in New Zealand were actually from lower or middle income families because it was affordable, and that richer families would have instead sent their children to the US or UK.[15] Roth also chimed in, stating that it was short-sighted to scapegoat international students during a time of economic crisis.

Not everyone was sympathetic. Aucklanders wrote to newspapers, saying that students “expect rich and poor New Zealand taxpayers to provide [for their] education”, or that they “can see no earthly reason why the New Zealand tax payer (sic.) should pay for these foreign students when they contribute nothing to the economy of this country.”[16]

It wasn’t just laypeople either. The University Grants and Universities Committee even stated in their annual report that, “It need hardly be pointed out that these students and their families contribute virtually nothing as taxpayers towards the costs of our universities.”[17]

Results?

Nonetheless, some progress was made. The government relented and agreed to exclude secondary students from this fee. This only spared less than 2% of the incoming students, as most were enrolling in tertiary institutions.[18]

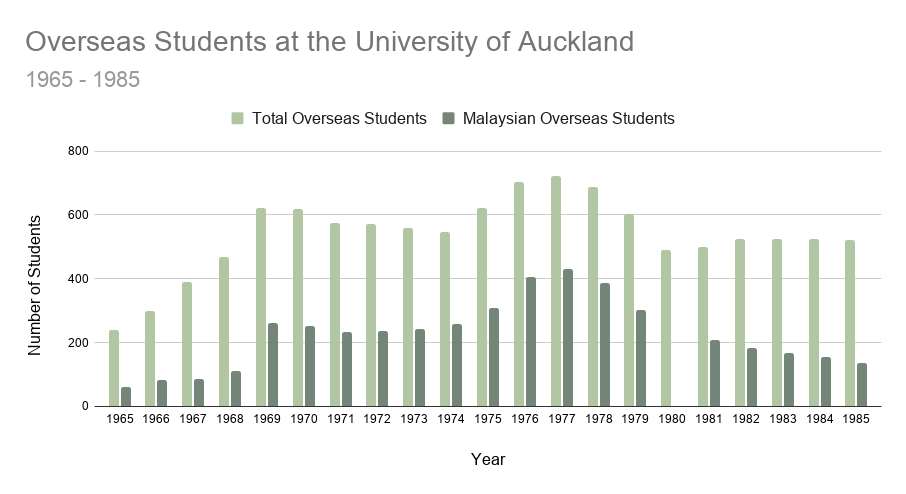

So what about the remaining 98%? Muldoon’s bold claims that the fee increase wouldn’t affect student numbers were unfounded. The University Grants and Universities Committee report of 1979 noted a significant decrease in the number of applications that year, and the number of overseas students decreased overall by 30% since 1977.[19] Figure 1 illustrates this decrease.

The number of overseas students at the University of Auckland between 1965 and 1985.[20]

Ironically, just a decade earlier, the then Minister of External Affairs said that “New Zealand would strain its resources to the limit and make any sacrifice to take in Malayan university students.”[21] The quota and the fee hike cannot, therefore, be viewed solely as an attempt to open education access to a broader range of countries. The combination of politics and diplomacy, immigration fears, and economic downturn led to a radical change in policy and perspective.

In their pursuit for higher education and standing up for their counterparts back home, Malaysian students in Auckland found themselves at the receiving end of several policies that singled them out. Despite their liminal position as temporary members of Auckland’s population, they took to the streets and to the papers, asserting their rights to be here and to receive a fair education. However, the quota and the fee hike were both imposed nonetheless, the first in a series of policies targeting tertiary education that would eventually hurt all students. In particular, the rising fees mark the changing attitudes toward international students and the birth of our now fifth-largest export industry – education.

The case study of Malaysian students at the University of Auckland demonstrates how the international student community in Auckland shifted from being perceived as a source of cultural curiosity and exchange to a political force, one vulnerable to the whims of their home and host government’s decision making. In times of crisis, outsiders are discarded first. The Malaysian international students would be the first victims in a series of policy decisions attacking our tertiary education sector. They did not take this lying down. Like students before and after them, they drew public attention to their plight, banding with allies in an ultimately unsuccessful endeavour.

The disposability of immigrants grew into anti-Asian sentiment in the late 1990s. In the early 2000s, fears of an “Inv-Asian” became prominent in particular at the University of Auckland.

These fears would resurface several years later, with the outbreak of COVID-19. The next article will explore how international students were viewed by their peers, other Aucklanders, and even overseas, and how fear and the economy have shaped the relationship between international students and the wider Auckland community.

[1]J.Collins, ‘Perspectives from the Periphery? Colombo Plan Scholars in New Zealand Universities, 1951‐1975’, ed. Peter Rushbrook, History of Education Review 41, no. 2 (2012), 136. https://doi.org/10.1108/08198691311269501.

[2]‘Private Foreign Students to Pay for Studies’, New Zealand Herald, 14 May 1979.

[3]‘Fees Hurt Overseas Students’, New Zealand Herald, 24 January 1980.

[4]Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (AJHR), 1970, E-3, 14-15.

[5]AJHR, 1972, E-3, 20.

[6]AJHR, 1974, E-21, 7.

[7]This is in reference to the national anthem of Singapore, Majulah Singapura (‘Onward Singapore’).

[8]‘Report on Fee Campaign’, Suara, 4, no. 4 (1979), 3.

[9]‘Protestors Meet Talboys’, Star Weekender (Auckland), 16 June 1979.

[10]‘Protesting Asians in March’, New Zealand Herald, 16 June 1979; ‘Students to March in Protest’, New Zealand Herald, 14 June 1979.

[11]‘Letters to Editor’, Suara, 4, no. 4 (1979), 20.

[12]Handbook for New Zealand Government Sponsored Overseas Students, Wellington, N.Z: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1988, 30.

[13]Suara, June-July (1978), 3.

[14]‘Part II: Focus – Fee-Hike’, Suara, 4, no. 3 (1979), 7.

[15]‘Attack on Student Pay-plan’, New Zealand Herald, 16 May 1979; ‘“We’re not all rich” Malay student says’, Auckland Star, 21 May 1979.

[16]Students’, Auckland Star, 6 July 1979; ‘Student Fees’, Auckland Star, 16 July 1979.

[17]AJHR, 1970, E-3, 15.

[18]‘Govt Lifts Fees For Some’, New Zealand Herald, 27 June 1979; ‘“Wipe Fees For All” Say Asian Students’, 25 June 1979, University of Auckland clipping books, 1979-81. MSS & Archives E-3, Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

[19]‘Overseas Roll Drops 30pc’, New Zealand Herald, 24 March 1980; AJHR, 1980, E-3, 9.

[20]‘University of Auckland’, In University Statistics, Wellington, N.Z.: University Grants Committee, 1966-1986, U1.3, U16 There was no data available regarding the number of Malaysian students at the University of Auckland in 1980.

[21]‘N.Z. Help for Students From Malaya: Minister’s Assurance of Interest’, New Zealand Herald, 5 November 1957.