Part Four

“Between Two Worlds”: Dalmatian Aucklanders

by Helena Wiseman*

“Our people have contributed a lot. We weren’t always appreciated, but we’ve been high achievers. We’ve done very well for ourselves”.[1]

Those were Auckland Dalmatian Tony Barbarich’s reflections on his experiences, and his community’s contributions to their society. The Dalmatian community is now notably integrated with wider Auckland. Dalmatian names are common and often well-known. Some of our most famous sports players have been Dalmatian, for example All White Ivan Vicelich and All Black Frano Botica.[2] Many Aucklanders would also strongly associate the Dalmatian contribution to Auckland with the vineyards and orchards of West Auckland. But this research, which began as an investigation into how Auckland city shaped Dalmatian newcomers, has revealed the extent to which those Dalmatian newcomers have shaped Auckland in return.

The industries that Dalmatians became involved with here are more varied than wine and kauri gum digging, and their involvement has been quite instrumental. The community’s role in the fisheries industry sheds light on the significance of Auckland as a Dalmatian diasporic settlement, and why they chose to come to this city to make their home. And so, to understand the ‘end’ of this story — the lasting impact Dalmatian Aucklanders have had on the city’s industries and institutions – we must return to the beginning, and to the home country.

The province of Dalmatia runs along the Adriatic coast of modern-day Croatia. Its villages sit high on cliffs or nestled on islands and overlook the Mediterranean.[3] At the time migration to Aotearoa New Zealand began, most of those settlements were subsistence-based. Villagers ate what they grew in the ground or caught at sea. As such, Dalmatians were historically useful to the various empires that annexed their country because they were exceptionally good mariners and fishermen: these were a people who loved the sea, and who viewed it as a window to the world.[4] There is a poetry in their choice of Auckland: City of Sails, land of two harbours.

It is unsurprising but equally unrecognised that Dalmatians became heavily involved in commercial fisheries. Today, one of our larger fisheries companies, Anton’s Fisheries, is still Dalmatian-owned.[5] Dalmatians also owned fish and chip shops, such as the ones on Hobson and Victoria Streets in 1950.[6] This was industry experience taken directly from Dalmatia and applied here. The use of the city’s harbour is something most Aucklanders may well identify as quintessentially ‘Auckland’, and in fact it had some Dalmatian foundations.

Horticulture was also integral to the Dalmatian way of life, and those skills have made their mark on Auckland as well. Most Aucklanders would be familiar with the Dalmatian-owned industries in West Auckland. Nola’s Orchard, and the Nola fruit shop, was so much a part of the Oratia community that when it burnt down in 2018, locals described it as “losing an institution”.[7] The locals saw the shop, located on the same roundabout on West Coast Road since 1935, as “iconic”, and a hub for their community.[8] Our story so far has been one of Dalmatians themselves using institutions and the cityscape of Auckland to forge their own social connections. But it is also one of the Dalmatian community, with their unique heritage, forming new networks and social hubs for every Aucklander.

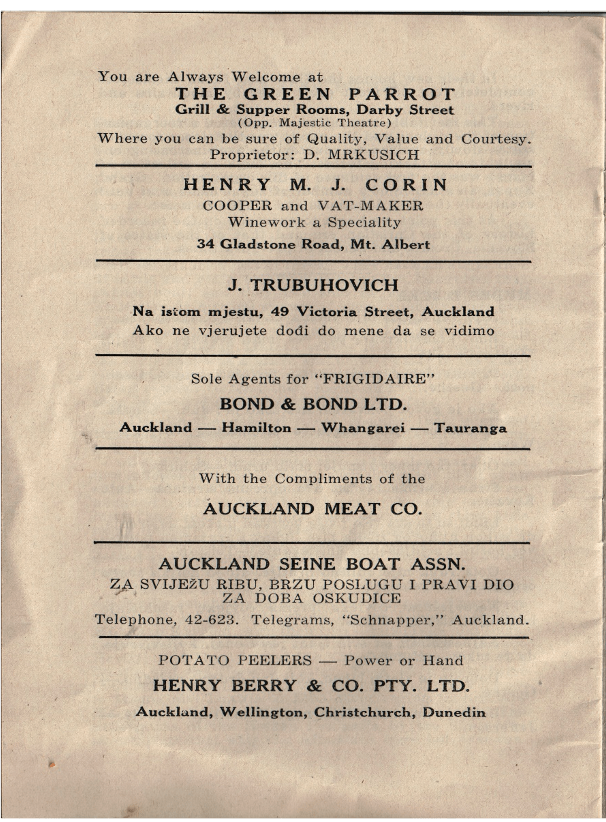

Advertisements for Dalmatian-owned businesses, including in maritime industries, from 1945 Picnic Programme. Source: Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Dalmatians in the Inner-City Box 1.

There are also institutions of Auckland which have helped build a sense of community, and which have become iconic in their own right, that were founded expressly so Dalmatians could begin to settle into Auckland. We can take football clubs as a case study.

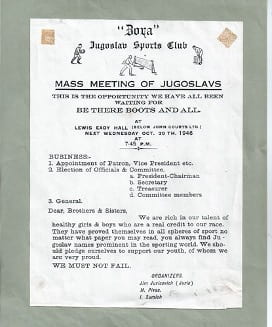

Football clubs were an important mechanism for social integration into Auckland for the Dalmatian community from the years after the Second World War. Dalmatians’ very first foray into sporting organisations in Auckland was through the formation of Jadran and Zora sports clubs in 1946. Sport was seen by the Yugoslav societies as a non-political, socially valuable way to build community networks in Auckland. Around 1946 the Herald reported that “members of the [Zora] club emphasised that the organisation was purely in the cause of sport and would not enter into any political or religious controversy”.[9] Rather, according to the advertisement for the club’s first ever meeting, the club “pledged itself in support of our youth”.[10] Zora had basketball (now netball) teams for women and girls, and a league football team for men and boys. Jadran was by solely a football club. Jadran means ‘Adriatic’, a reference to the coastline they came from, and, as Alick Dracevich recalled, was a way for Dalmatians to participate in their national sport together.[11]

Figure 2. Advertisement for the establishment of Zora. Source: Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Folder Z/S/3.

From Jadran grew other football clubs, including the most notable of them all: Central United. Founded in the 1960s, Central United Football Club is now located on Kiwitea Street, Sandringham, near the core of the inner-city Dalmatian community. Its logo includes the Croatian check, and its Dalmatian heritage is celebrated. Central has become one of Auckland’s most iconic and successful football clubs, and hosts the National League side Auckland City, who once won third place representing Auckland at the Club World Cup. Their team line-up did not lack for Dalmatian last names, either.[12]

The symbiotic relationship between Auckland society and its Dalmatian community speaks clearly when considering the example of Central Football Club. The club relied on Auckland’s central suburbs to give it geographical foundations. Using those foundations, the club’s purpose was to give Dalmatians an opportunity to come together. Founding member Davor Antunovich recalled how the club helped the community. “Somewhere to belong to make us more content. We had somewhere to belong to, and we could express our feelings in our own language. It hasn’t been easy being immigrants […] it is very hard. The moment you migrate, you put yourself between two worlds”.[13]

Figure 3. Central United Football Club 50th Jubilee Celebrations advert, 2012. Source: Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archive, Folder Z/S/3 Page 60.

Central Football Club typifies that process. The club was a place to play Dalmatians’ national sport and speak in their native tongue, where the shared experiences of moving to Auckland could be discussed in between plays. But the club is more than that. It is part of the fabric of Auckland city, an iconic institution, and a place where many immigrants from other countries eventually came to play sport and build the networks we have seen to be so important as Auckland’s notable ‘super-diversity’ developed.[14] Without ever forgetting its Dalmatian origins, Central Football Club has become an Auckland sporting institution in its own right – a duality that has run throughout this history.

When Dalmatians came to Auckland, they sought out ways to make a home here, and each method doubled as a tie extending thousands of kilometres over several seas to Dalmatia. Fisheries, agriculture, vineyards; picnics at our beaches, the kolo in our ballrooms, Yugoslav politics in our newspapers – all were features of what it meant to be Dalmatian, and were recalibrated into the search for what it meant to be a Dalmatian Aucklander.

The Dalmatian community never settled for mere acceptance and assimilation – they were never so willing to leave their beloved homeland behind. Instead, they found ways to balance two identities. Because they did, they have given Auckland city’s institutions and history a distinctly Yugoslav character. They have helped write this story, so complex to tell, of a Dalmatian Auckland.

[1]Tony Barbarich, oral history, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Collection, Auckland Central Libraries Special Collections.

[2]Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Museum display.

[3]Andrew Trlin, Now Respected, Once Despised: Yugoslavs in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1979.

[4]Stephen Jelicich,’The Yugoslav community’, lecture, 1990, University of Auckland Special Collections, New Zealand Glass Case, Cassette LC90-42.

[5]Tony Barbarich, oral history, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Collection, Auckland Central Libraries Special Collections.

[6]Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Museum.

[7]TVNZ, ‘More than just a fruit shop – community devastated after fire guts iconic West Auckland store’, December 26, 2018, tvnz.co.nz/one-mews/new-zealand/more-than-just-a-fruit-shop-community-devastated-after-fire-guts-iconic-west-auckland-shop.

[8]TVNZ, ‘More than just a fruit shop – community devastated after fire guts iconic West Auckland store’, December 26, 2018, tvnz.co.nz/one-mews/new-zealand/more-than-just-a-fruit-shop-community-devastated-after-fire-guts-iconic-west-auckland-shop.

[9]New Zealand Herald, ‘Auckland Yugoslavs form sports club’ c. 1946, DGHS_Z_S_S, page 29, Book 2, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Collection, Auckland Central Libraries Online Collection.

[10]Folder Z/S/3, Page 12, Dalmatian Genealogical and Historical Society Archives.

[11]Alick Dracevich, oral history, 2015, Record WOH-1040-023, Glen Eden Histories Collection, Auckland Central Library Special Collections.

[12]Jeremy Ruane, ‘History’, centralunitedfc.co.nz/history. Accessed 30 November 2020.

[13]Stuart Graeme McAdam, ‘Yellow Fever: Stories of a Soccer Community’, Honours Research Project, Social Anthropology, Massey University Auckland 2004.

[14]Stuart Graeme McAdam, ‘Yellow Fever: Stories of a Soccer Community’, Honours Research Project, Social Anthropology, Massey University Auckland 2004.