Part Four

Leaving home and coming home

by Slavenka Misa (nee Sumich)

Belonging, identity and citizenship were in a flux. Dalmatian New Zealanders began to apply to return to New Zealand before the end of 1948; disillusioned with Yugoslavia they were keen to return ‘home’. Some returnees, desperate and despairing of obtaining official permission and papers for their departure tried to flee over the Italian border. All returnees relied on the generosity of friends and relatives to enable them to purchase a ticket to return to New Zealand as any money brought from New Zealand and deposited in a Yugoslav bank account was retained by the Yugoslav government. The NZ Minister of Foreign Affairs, Peter Fraser, had warned in September 1948 that

NZ has no treaty with Yugoslavia…on the subject of dual nationality and British subjects who are of Yugoslav birth or origin should note that they are liable to be claimed by the Yugoslav authorities as citizens of Yugoslavia…Accordingly , British subjects by naturalization in New Zealand whom the Yugoslav authorities regard as Yugoslav citizens may not be able to obtain permission from the Yugoslav authorities to leave Yugoslavia.

The New Zealand government is also informed that the Yugoslav citizens are also citizens of Yugoslavia even though they, as well as their parents, may have been born in New Zealand.

These warnings came too late for those who had sailed on the Radnik.

Young male returnees who had been born in Yugoslavia but had not served in New Zealand armed forces during the War had to serve two years in the Yugoslav army before their requests to return to New Zealand were even considered. All who travelled back to New Zealand were issued with Yugoslav passports valid for six months as their British passports had been confiscated by the Yugoslav government.

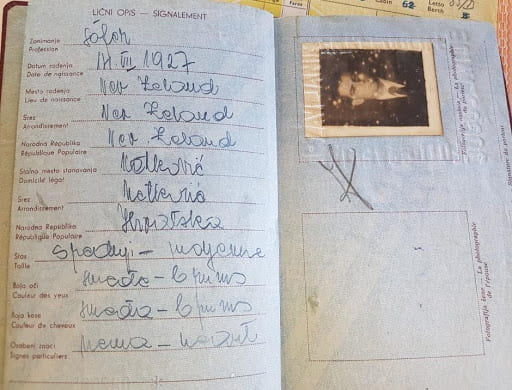

Ivan Sumich had already served in the New Zealand army during the war so was exempt from military service. But despite being a naturalized British subject, he had been born in Yugoslavia, and the regime was reluctant to allow him to return to New Zealand. He took three years to negotiate his passage; a time fraught with uncertainty, before he acquired the right to leave in 1951. He spent most of his three year stay in Yugoslavia working for his father on the family small holdings, helping others in the village of Podgora and striving to retrieve his British passport. The Yugoslav government refused to recognise his New Zealand naturalization and it took years of applications, letters, interviews, and fruitless visits to offices before he was finally granted permission and documents to leave Yugoslavia and return to New Zealand on a Yugoslav passport in 1951.

Steve Mrkusic, Gordon, and Victor Sunde were born in New Zealand, but it still took them about twenty months to retrieve their British passports and gain permission to leave Yugoslavia. They were all too young to have served in the New Zealand forces during the War and because they were not Yugoslav born, they escaped conscription into the Yugoslav military.

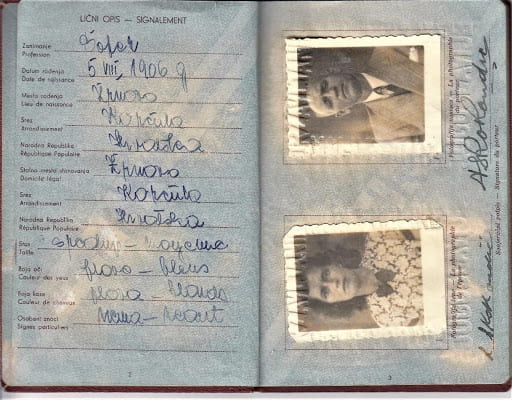

New Zealand born Boris Yelavich had sailed on the Radnik as a twenty-year old young farmer from Papakura on his New Zealand passport but returned to New Zealand from Yugoslavia in September 1951 on a Yugoslav passport.

The Yugoslav passport of Boris Yelavich recorded his occupation as ‘driver’ (šofer}. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF MARY SEYMOUR.

Boris Yelavich travelled on the Toscana with a large group of returnees most of whom were bound for Australia. He is standing behind the women, first man from the right, wearing an open collared shirt and dark jacket. PHOTO COURTESY OF MARY SEYMOUR.

Steve, Gordon, and Victor left Yugoslavia near the end of December 1949; their passage paid for by relatives in New Zealand. They travelled from Zagreb on the Orient Express to Venice and then on to Genoa where they booked first class passage on the Sebastian Caboto (Lloyd Triestino Line) leaving for Melbourne. The demand was high for berths onboard vessels sailing for the Southern hemisphere and prospective passengers could find themselves waiting weeks for a cabin. First Class may have been the most expedient choice rather than paying for longer accommodation in Genoa. It was certainly a pleasant and appreciated change for the young men after the rigors of post war Yugoslavia.

The postcard of the historic 76 metre lighthouse sent from Genoa by Steve Mrkusic to Ivan Sumich telling him that his cousin had arrived there safely. Steve commented that “the Italians are an easy-going people, there is no rushing around here”. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA

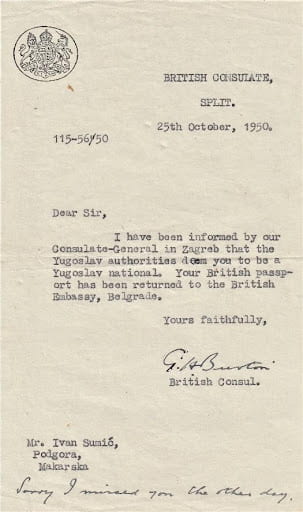

In March 1950, Ivan Sumich made a special visit to Belgrade to apply for travel documents. He was given a “Confirmation of Acceptance of the Report of his Notice of Departure”. He also had the vaccinations required for his travels while he was there. However, in October the British Consul in Split wrote to him to say that

the Yugoslav authorities deem you to be a Yugoslav national. Your British passport has been returned to the British Embassy, Belgrade.

Letter to Ivan Sumich from the British Consul in Split confirming that his British passport was out of reach. Mr Burton added a note saying, “sorry I missed you the other day”. They must have become well known to each other. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

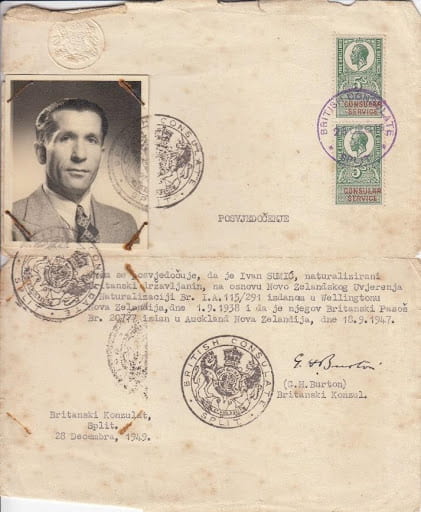

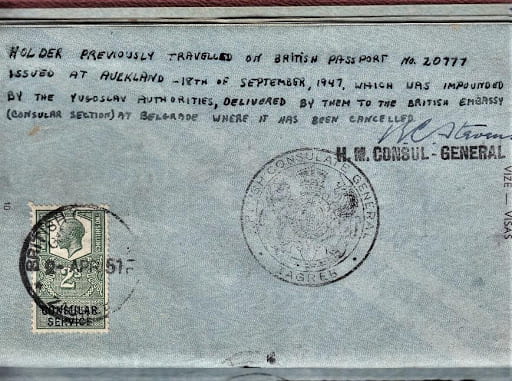

Eventually, on 31 March 1951, Ivan was granted a Yugoslav passport and visa to leave for New Zealand. It was valid for six months. The British Consulate added information (on 2nd April 1951) to Ivan’s Yugoslav passport: references to his New Zealand naturalization and citizenship, the number of his previous British passport, and a Commonwealth visa to travel to New Zealand.

The British Consul provided a document in Serbo-Croatian confirming Ivan’s New Zealand citizenship. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

Cover of Ivan’s Yugoslav passport. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA

The paragraph written on this page of Ivan’s Yugoslav passport confirmed the fact that Ivan had possessed a British passport and described what had become of it. The facing page described him as a citizen of the Commonwealth of New Zealand.

He set sail for New Zealand from Genoa on 15 May 1951. A cousin in Wellington had helped pay for his passage. Ivan travelled by train from Zagreb to Genoa, arriving on 3rd May. He spent twelve days waiting in Genoa before taking a third-class berth on the S.S. Surriento which departed on 15th May 1951. He had company in Genoa meeting a group of West Australian returnees who had also waited several years before being granted permission to leave Yugoslavia. The stay in Genoa was a pleasant interlude compared with the tribulations of the previous years. The Surriento sailed to Sydney via Fremantle so Ivan had the returning West Australians as companions for the journey.

Ivan Sumich aboard the Surriento at the port of Fremantle where he farewelled his West Australian friends. PHOTO COURTESY OF SLAVENKA

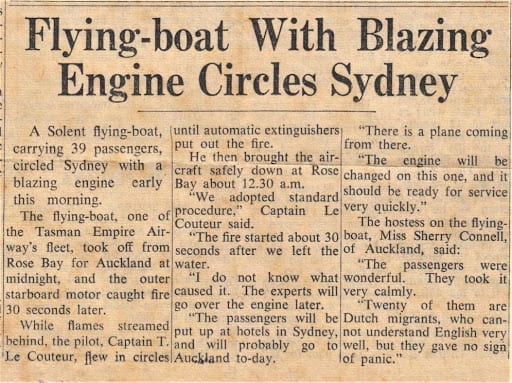

The final leg of Ivan’s journey from Sydney to Auckland was by Tasman Empire Airlines flying boat. It proved to be a dramatic experience. The plane developed a fire in one of its engines shortly after taking off at midnight. It flew around in circles with flames streaming behind it for nearly half an hour until the fire was stifled and the plane landed at 12:30 am. Ivan boarded the replacement plane the next day for a normal flight to Mechanics Bay on the shores of the Waitemata harbour, Auckland.

Ivan went to the cousin in Wellington who had loaned him money for his fare and spent several months working for him before returning to work as a stevedore in Auckland.

The dramatic engine fire onboard the flying-boat made the front page of The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 June 1951. Ivan Sumich kept this news clipping for the rest of his life. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

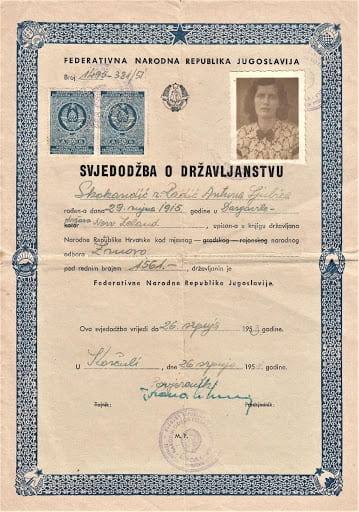

The Skokandich family travelled on the new Yugoslav passport of Nikola Skokandich (senior), the Skokandich children and their mother were also claimed as Yugoslav citizens. The children, Barbara, and Nick as well as their mother, Violet were born in New Zealand but since Mr Skokandich was Yugoslav born and they were his family they were included on his passport. They also made the sea leg of their return journey on board the Toscana though on a later voyage than Boris Yelavich.

Violet Skokandich’s Yugoslav Citizenship Certificate which was valid for two years. Yugoslav citizenship allowed her to be included on her husband’s passport and thus permitted to leave Yugoslavia. Violet and the children had also been included in the British passport of her husband when they left New Zealand in 1948. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF NICK SKOKANDICH.

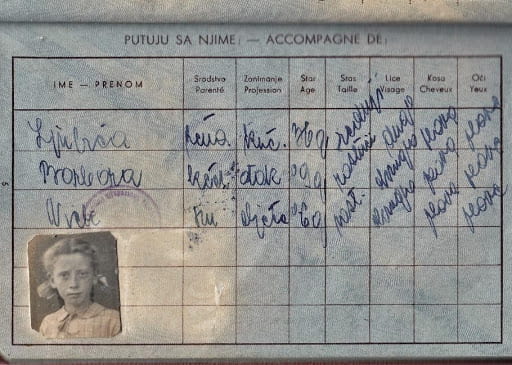

The Skokandich family’s Yugoslav passport. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF NICH SKOKANDICH.

This page lists the family members travelling on Nikola Skokandich’s passport; his wife Ljubica (Violet), daughter Barbara, and son Nick. Nick’s photograph has been lost as the glue dried up and the photo became loose.

Barbara and Nick Skokandich were young children (9 and 6 years old) when their parents packed up the family in December 1951 for their return. Their father had decided that his son and daughter would have a better future in New Zealand than in Yugoslavia. They enjoyed their journey back to New Zealand. The cooks in the galley would give them treats and Nick even had a tour of the engine room.

Nick was a seven-year-old by the time the family arrived in Sydney. They were to stay with relations while they arranged to sail to Auckland. Sydney impressed Nick.

Even arriving in Sydney, going to my cousin’s place in Blacktown (was great). We went up the main drag in this guy’s ’39 Chevrolet…and seeing all the cars…because I don’t remember the port (in Italy) where we got on the boat… or Perth where we stopped (Fremantle).

To Nick’s delight the family flew from Sydney by TEAL flying boat to Mechanics Bay, Auckland.

I remember looking out the window, as we took off, at the spray…the bumping through the top of the waves. Then we had to land again and go through the whole thing again, a second time, for the flight to Auckland because the engine broke-down. They were quite unreliable, the British motors. As we were actually taking off it stopped.

I don’t remember being tied down, seatbelts or anything. I can’t remember if I was next to the window, but I remember looking out the window. All the action… it was fantastic. As a little kid I was just beside myself.

This certificate was posted to young Nick by TEAL as a souvenir of his flight. Air travel was unusual and special in 1951. The name of the plane and the captain’s signature have faded. The plane was the AMO Aranui which is now restored and on display at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Auckland. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF NICK SKOKANDICH.

Starting again and settling in at ‘home’

The Skokandich family returned to Dargaville where Nick and Barbara’s maternal grandparents lived. They had paid the fares for the family’s travel. Settling into life in NZ would be harder for the children than for the adults because the children had forgotten how to speak English. Violet had received occasional newspapers and magazines in packages from her sister in NZ even though she had little opportunity to use or hear spoken English. However, English had been completely absent from the children’s world.

Nick was placed in the new entrants’ class as he had only just started school in the village of Žrnovo. He was a tall boy of seven while his classmates were two years younger. Barbara struggled to understand what was expected of her; copying what the others in her class did until she acquired some vocabulary. The complicated spelling system of English was a nasty surprise after the logical phonetic alphabet of the Serbo-Croatian language. When first called on to read aloud in class Barbara’s Croatian phonetics led to mispronunciations that amused her classmates.

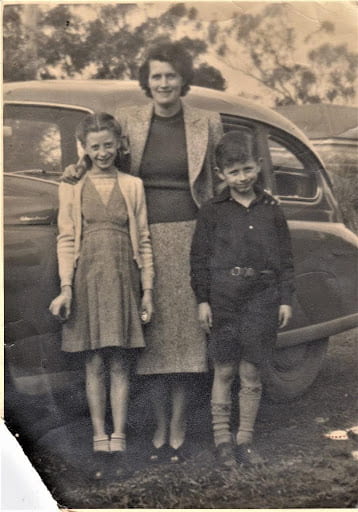

Barbara, mother Violet Skokandich, and brother Nick back home in Dargaville c. 1951. PHOTO COURTESY OF NICK SKOKANDICH.

For the young men, Steve Mrkusic, Gordon, and Victor Sunde, returning to New Zealand was a relief. Steve quickly picked up where he had left off.

Within days I obtained a job as junior draughtsman in the architects’ office of the Auckland Education Board. In 1951 the University of Auckland accepted my application to study architecture as a part time student. I completed final subjects in 1955 and obtained registration as an architect in 1957. Education became my field of expertise, culminating in my appointment in 1963 as Chief Architect of the Hamilton Education Board, a position I held for 28 years.

Victor assumed management of the P.&D. Sunde fruit orchard which prospered. He concentrated his efforts in promoting New Zealand fruit exports to Europe and was successful. He was chairman of the New Zealand Fruit-growers Federation for many years.

Gordon returned to his parents on their Oratia orchard with his socialist ideals still intact despite what he had seen in Yugoslavia. He owned a successful dry-cleaning business and was actively involved as a committee member of the Dalmatian Cultural Society serving a term as president.

He joined the Labour party and actively supported his electorate Member of Parliament. He was involved in community affairs as a member of the executive of the Waitakere Licensing Trust and as chairman. The Trust funded many cultural, charitable, and sporting activities. In 1998 he was elected to the Waitakere City Council.

Krešimir Jakich, who had worked in the Volunteer Brigade with Ivan, Gordon, Victor and Steve, stayed a little longer in Yugoslavia. He married and took his new bride back to Wellington in 1952. There they ran a fish shop and were loyal members of the Wellington Yugoslav Club.

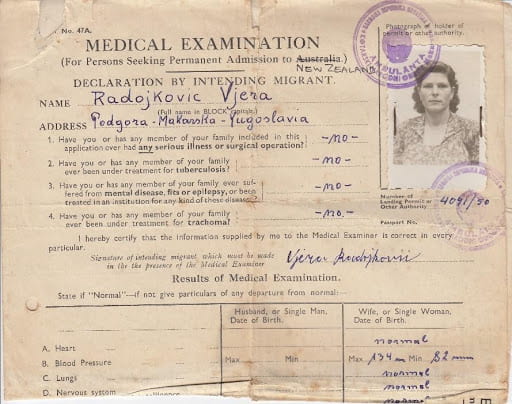

Ivan Sumich, left his fiancée, Vjera Radojković, in Yugoslavia to wait for the arrival of her Permit to Enter New Zealand. Ivan applied for Vjera’s Permit soon after he arrived in New Zealand. A supporting letter was written to John Massey M.P. by Simun Mercep, a well-known and respected member of the Yugoslav community. Nevertheless, Ivan was advised by the Minister of Immigration in October 1951 that he should reapply in six months’ time. It was early September 1952 when Ivan received a letter confirming that the entry permit was granted providing that £100 was lodged with the Collector of Customs, Auckland. They also required two passport size photographs of Vjera and copies of her medical and X-ray certificates.

Ivan completed all that was asked of him but there was still no sign of the Permit in November. Cables and letters were exchanged until finally the Department of Labour and Employment, Immigration Division wrote on 11th December 1952 to say that ‘… Miss Radojkovic’s permit has been dispatched to the British Representatives in Yugoslavia, and she should shortly be hearing from them.’ This was a massive relief as her Yugoslav passport was valid for only one year. Because of all the delays, it expired the day before she arrived in Fremantle. Fortunately, common sense prevailed, and when Vjera landed in Auckland her entry permit was accepted. Ivan and Vjera’s experience, is just one example of the bureaucratic labyrinth that had to be negotiated by the returnees. On one side was a government reluctant to release its citizens

Part of a medical document provided for the application for Vjera Radojković’s Entry Permit. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

and on the other a government unenthusiastic about ‘Balkan’ immigrants. During the 1950s New Zealand encouraged immigration only from Britain and Northern European countries such as the Netherlands.

Conclusion

By 1955, almost all of the Australian contingent had returned to Australia richer for their experience but poorer in pocket. It is not certain how many returned to New Zealand, but of the nineteen men who went back to the village of Podgora on the Adriatic coast, ten returned to New Zealand. That may be a representative example indicating that about half of the returnees from New Zealand made their way back ‘home’ as soon as they could. Many of the men who boarded the ships in Auckland were over 50 and were almost certainly going home to live out their sunset years with their families.

This episode is part of the story of migration, of the search for a better life, of idealism, love of family, home and patriotism which fueled the desire to return to what was thought to be a reincarnated, improved Yugoslavia. When the New Zealanders arrived, they found that the country was not a place where many of the returnees could see a good future for themselves or their children. They knew that New Zealand offered them a better one.

Any readers interested in discovering more about their Dalmatian roots or generally interested in the history of Dalmatians in Aotearoa New Zealand please contact the Dalmatian Archive and Museum

P.O.Box 8479

Symonds Street

Auckland 1010

Phone (09)303 0366

The DA&M is part of the Dalmatian Cultural Society and is housed on the ground floor of their building at

10 New North Road

Eden Terrace

Auckland