Part Two

The Voyage

by Slavenka Misa*

The Ships

The two Yugoslav ships that carried out the repatriation voyages were bought with the express purpose of repatriating young fit Yugoslavs living overseas. Both ships were old and had served as troopships. The Partizanka had better passenger facilities than the Radnik which was a cargo ship. After the repatriation voyages to Yugoslavia neither served any further purpose. The Radnik and Partizanka made ten repatriation voyages between 1947 and 1951 taking 4060 returnees from South America, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. They carried fare paying emigrants from Europe and the Middle East on their outward journeys and enthusiastic returnees back to the Adriatic ports.

The Radnik arrived in Auckland in February 1948 to take onboard 100 passengers, including one stowaway. The Partizanka arrived in January 1949 to take 23 passengers, including two stowaways.The returnees were expected to pay a fare according to their financial status. Ivan Sumich paid ₤95 plus ₤4-15 shillings passage tax. Post war Yugoslavia needed manpower and economic input to enable reconstruction. The returnees were bringing themselves and their worldly goods to benefit the building of a new Yugoslavia. Hundreds more returnees boarded in Australia (from Sydney and Fremantle). The Australian returnees would, within five years, almost all come back to Australia, as would those from New Zealand.

The Radnik was built in 1908 with space for 64 passengers. It was primarily a cargo vessel. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM.

About 300 Yugoslavs from NZ travelled in this immediate postwar period. The largest group were single men returning to their families after being detained by years of economic depression and war. Only three families made the journey and a total of eleven women. Those passengers leaving from Australia consisted of a far greater proportion of well-established families whose menfolk were driven by several forces: patriotism, idealism, family ties and their hope for a better life away from the racial prejudice they had experienced in Australia. The New Zealanders shared the feelings of the Australians but their experiences in New Zealand were, in general, less extreme (politically, socially and climatically) which could explain why they were less likely to make the radical decision to uproot their families.

A group of 59 Yugoslavs had already, independently, set sail in August 1947 on the Rangitiki bound for Yugoslavia. The New Zealand government was aware of this and even as the arrival of the Radnik was imminent there were rumours regarding pressure being put upon Yugoslav settlers and their families, by Tito’s regime, to return to Yugoslavia. However, in Kaitaia prominent members of the Dalmatian community pointed out that the returnees from their area were mostly older men who had come to New Zealand for work and whose families were awaiting their return which had been delayed by the war.

The New Zealand government distrusted those presumed to have a connection to a communist regime. The Cold War, which had begun in 1947 made the New Zealand government suspicious of any activities that could be labelled ‘communist’. Four Yugoslav men from Whangarei who had booked passage on the Radnik felt the need to respond to previous allegations in the press by stating that ‘… no pressure whatever had been brought to bear on them to return to their home country. Their main reason for going to Yugoslavia was to rejoin their wives and children.’ Two of the men had lived in New Zealand for over twenty years and all four had wives and children in Yugoslavia. Before the war, their families had hoped to come to New Zealand but now their letters asked for the men to return to a new Yugoslavia.

The Arrival of the Radnik

The Radnik was greeted by a flotilla of boats on 10 February 1948 as she waited at anchor in the Waitemata Harbour for a berth. Seventy-five per cent of the fishing industry in Auckland was then Yugoslav owned and a multitude of fishing vessels, owned by Yugoslav New Zealanders surrounded the boat, welcoming her to the country.

Excitement was high among the Yugoslav community. Intrepid and enthusiastic visitors came alongside and were assisted up the rope ladders hanging down the side of the Radnik. They were overwhelmed to see a ship from ‘home’ and to be hospitably welcomed aboard. Crowds came to look at the ship berthed at the wharf and to hear news of family and friends direct from survivors of WW2.

The Radnik at anchor in the Waitemata harbour with the fishing boats St. Vincent and St. George alongside. The rope ladders which visitors used to clamber aboard the ship are visible. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM.

Captain Lončarić of the Radnik with visitors at Auckland. L to R, Rita Bercich, Lucy Bakarich, Ana Botica, Ivy Babich, Tereza Bercich. It was a day to celebrate and wear one’s best clothes. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM

The captain and crew were shown great hospitality by the New Zealand Yugoslav community. Vehicles were put at their disposal, local produce and wines were donated and delivered to the crew. A dinner and dance was held in their honour at the Yugoslav Club Marshall Tito. People who were remaining in New Zealand wanted to send goods to their families back home and many crates were filled with clothing, food, and other domestic items and delivered to the wharf. Sugar was still a rationed commodity, until August 1948, and a permit was required for the export of flour, but these essential items were routinely hidden among second-hand clothing which was allowed to be sent without limitation. The crates were large and cumbersome and at least one proved problematic.

At the Lavus boarding house in Hobson Street there was a large backyard with a lean-to roof against the two storey building. This was a handy place to put together and fill a big, wooden packing case. Jessie Posa (nee Telenta) remembers,

(Mr Lavus) must have wanted to have a big box, he must have thought “ja ču big box”, you know, and so he filled it all up. And when they went to load it onto the truck, they couldn’t get it through the passageway. It was a fairly big boarding house, it was a two storey house, and it wasn’t as if it (the box) was… an average size… and so they didn’t know what to do.

There was no alley or driveway between the buildings.

I heard about it because Francie Lavus was my friend, we were exactly the same age. I was up there all the time with Francie and we all knew about what happened. The carrier who used to bring us all the potatoes to cook the chips… he was the carrier who came to collect (the packing case)…. But they “couldn’t get the bloody box out…”, it was quite funny at the time.

The men involved were determined and eventually solved their problem with the cooperation of the publican of the Prince Arthur Hotel. This hotel shared a fence with the Lavus property. Some of the fence was removed and the crate man-handled into the hotel’s yard. Where it could be collected and taken by truck to the wharf.

Tom Cibilich (smoking) waiting to unload his father’s luggage (Visko Cibilich) who was departing on the Partizanka January 1949. Note the large box in the back of the truck. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM

Leaving

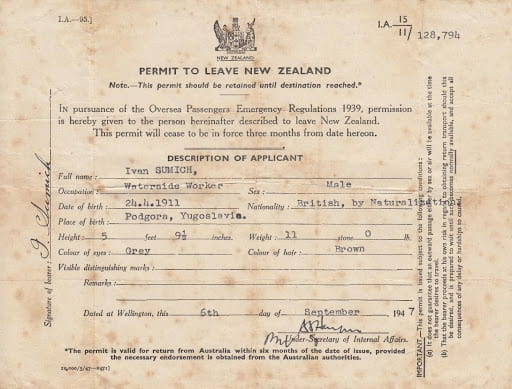

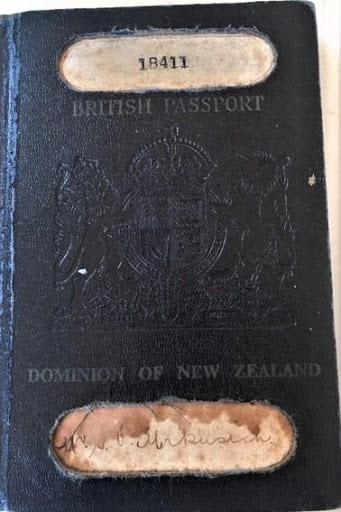

Preparations to leave had begun months before the arrival of the Radnik. Marin Ivicevich, secretary of the Yugoslav Association (Savez) (footnote explanation previous article) was an enthusiastic supporter of the repatriation movement and published advice to prospective returnees in the Napredak. He described how many photographs would be required for the documentation and how to apply for Yugoslav passports, or British passports for those who were New Zealand born or naturalised, as well as the necessary Permit to Leave New Zealand. He encouraged all travellers to make haste to complete their documentation.

Ivan Sumich’s Departure Permit. Sumich also travelled on a British Passport?ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA

Generous fund raising had paid for 450 bales of wool and 1200 sacks of hides to send to Yugoslavia. One hundred Romney sheep, a gift to the Yugoslav government from the Yugoslav community in New Zealand, were loaded on the Radnik as well as the belongings and baggage that the returnees were permitted to take. There was a delay in loading caused by disagreement over the commission rate to be paid to the shipping company. Many local Yugoslav men came to help move the cargo on to the ship and ensure its timely sailing. As well as their goods, equipment and clothing passengers on the Radnik in February 1948 were permitted to take food for the journey.

Nikola Skokandich had sold his car but took his hunting rifle and hunting dog so that he could be sure of feeding his family when they arrived on the island of Korčula. His six-year-old daughter and three-year-old son had their tricycle and pedal car with them which they would ride on the deck of the ship. Ivan Sumich took his ‘J Force’ memento, a samurai sword. The sword became a treasured possession of his father in Podgora, Dalmatia, after Ivan returned permanently to New Zealand.

Steve Mrkusic took

‘… everything personal, including bicycle, 22 rifle and ammo plus saleable items that were not available in Yugoslavia i.e. nylon combs, safety razor blades and sewing needles’.

The Radnik about to sail. Third from Left is Steve Mrkusic, Ivan Sumich (in white shirt and tie) then the Skokandich family. Violet partly obscured, young Barbara and brother Nick by the rail with Nikola their father behind them. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM

Gordon Sunde waving goodbye from the Radnik. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM.

The departure of the Radnik as described in the newspapers at the time was a moving occasion.

Slav songs centuries old rang out over the wharves …as the steamer Radnik… slowly, pulled away from Hobson wharf, breaking the streamers which linked passengers with about 2000 of their compatriots who had come to see them off.

There were tears on both sides as some of the passengers were leaving after living for decades in New Zealand. Eleven passengers would be setting foot in Yugoslavia for the first time in their lives.

Crowds at the wharf to farewell the Radnik passengers. Note Eutirija Jelicich, Chairwoman of the Ladies committee of the Yugoslav Cub Marshal Tito, first face in front on left, with her hair in a braid around her head. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE DALMATIAN ARCHIVE AND MUSEUM.

Accommodation onboard was basic. Steve Mrkusic recalls there were

no individual cabins. Sleeping was on tiered bunks in two ex-cargo holds, no privacy, ablutions were communal… Despite the above limitations we were a happy ship. The captain and crew were always helpful. Food was always appetizing and plentiful.

Gordon Sunde, who was looking forward to being part of the New Zealand contingent volunteering in the youth brigades in Yugoslavia, also enjoyed his voyage on the Radnik. He wrote a letter home on the first leg between Auckland and Sydney saying

I am very satisfied with everything on board. The food is excellent…my travelling companions feel content and lucky that they are travelling together…The sea is calm and only one lady is a bit seasick. We have enough to entertain us and listen to the gramophone and radio. We take our turn looking after the sheep (a gift which New Zealand immigrants are sending to their homeland) …a lot of attention is paid to hygiene and cleanliness. We have a barbershop and baths…”.

85 passengers boarded in Sydney and the Radnik sailed for Fremantle where 162 more came aboard. Once again there was a massive crowd waiting on the Fremantle docks to welcome and farewell the Radnik and amongst the crowd were relatives of the New Zealand passengers.

Twenty-one Corriedale sheep and three pure bred Merinos were added to the deck flock in Fremantle. The animals were well cared for. Steve Mrkusic explains they ‘ …were housed on the top deck in special timber pens that required sluicing every day. There was no smell.’ All the sheep arrived safe and well in Yugoslavia after which no more is known of them.

It is suspected they did not survive to be a breeding flock. There were too many hungry people in Yugoslavia.

A further large amount of cargo was loaded in Fremantle. Some people took all their belongings and tools of trade. The Vlahov family took a rotary hoe, pipes, shovels, rakes and seeds to start a market garden in Yugoslavia. One man took his Vauxhall car which he used as a taxi in Yugoslavia. Heavy machinery such as trucks and tractors were not a permitted export.

The Yugoslav government was short of funds which meant the ship travelled at a modest speed to increase fuel economy. Steve Mrkusic remembers, ‘… the trip took 49 days from Auckland to Split… The weather for the Indian Ocean stretch, which took 19 days, was lovely.’ With the addition of the Australian passengers there were 75 women and 35 children on the Radnik. The female crew members organised a party on board for 8th March, International Women’s Day. Anzac Day was also celebrated on 25th April by the passengers. However when the ship stopped at Colombo none of the passengers on the ship were allowed to alight because it was feared that some would ‘jump ship’. Members of the ‘secret police’ were among the crew and they monitored the passengers.

Arrival in Yugoslavia

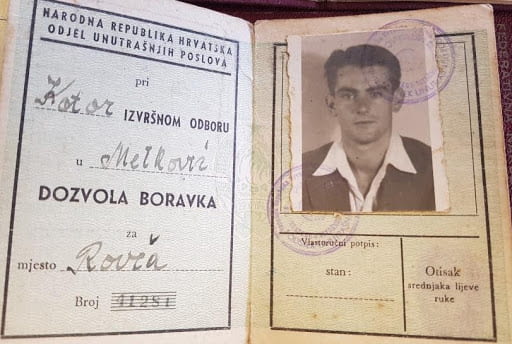

The Radnik anchored in the Adriatic, off the island of Vis and Yugoslav government officials came aboard and collected everyone’s passports. The passengers had not expected to relinquish their precious documents and Steve Mrkusic was unhappy.

I was a British subject and a New Zealand citizen. My British passport was confiscated by Yugoslav authorities at the island of Vis. The original intention was to stay in Yugoslavia for an indefinite period. Confiscating my passport was an unfriendly act.

Steve Mrkusic finally retrieved his British passport, late in 1949 and returned to New Zealand.

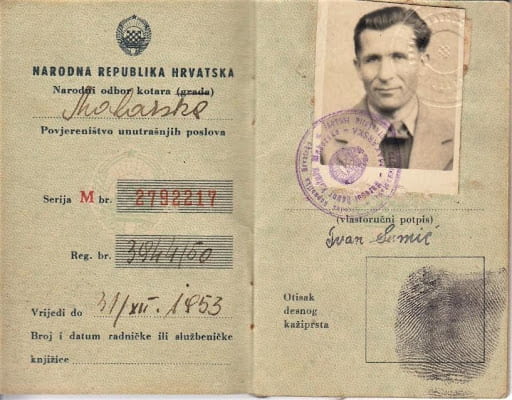

On entering Yugoslavia, the returnees were all given new citizenship documents and their money was exchanged for Yugoslav currency. The newcomers were not aware until later that the exchange rate on the ship was very unfair.

The welcome for the arrival of the Radnik in Split was very warm. A massive crowd of people had squeezed into the festively decorated port area to welcome the returning migrants. In the main they were family and friends awaiting their nearest and dearest but no doubt there were some curiousity seekers. There was an official welcome with speeches and a navy band played marches and folk songs while a choir of migrants sang the national anthem, ‘Hej, Slaveni’, from the ship.

Identity pass belonging to Ivan Sumich who was a Yugoslav citizen. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

Resident’s permit belonging to Boris Yelavich. Boris was New Zealand born so not a citizen of Yugoslavia. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF MARY SEYMOUR.

It was spring when the Radnik berthed in Split. Passengers were reunited with family and despite relinquishing their passports, there was still a sense of optimism and hope amongst the new arrivals.

The Partizanka, came to Auckland almost a year later, on January 18, 1949. It was impatiently awaited by the Dalmatian community who were desperate for the opportunity to send material aid to their families in Yugoslavia and about 1200 gift packages had been consigned by 900 donors. However, only twenty-one people had booked a passage home possibly because they were aware of the adverse experiences of those on the Radnik.

The Partizanka was prevented from sailing for four days because food items were found to be hidden inside crates of permitted secondhand clothing and tools. The Export Prohibition Emergency Regulations 1939 were still in effect and the Minister of Customs had forbidden the export of any food on this ship. Unloading and inspecting the entire cargo would be a costly, time-consuming exercise which no-one wanted. All concerned were incensed about the situation. On one side were the people who saw the humanitarian need and on the other, those who upheld the law. Eventually, on Sunday, January 23, a compromise was reached. Most of the gift parcels were left onboard and a penalty bond was to be paid to cover possible pending prosecutions and the ship sailed for Sydney on Monday morning 24 January 1949.

Any readers interested in discovering more about their Dalmatian roots or generally interested in the history of Dalmatians in Aotearoa New Zealand please contact the Dalmatian Archive and Museum

P.O.Box 8479

Symonds Street

Auckland 1010

Phone (09)303 0366

The DA&M is part of the Dalmatian Cultural Society and is housed on the ground floor of their building at

10 New North Road

Eden Terrace

Auckland