Part One

What’s in a Building? – Chelsea Sugar Refinery and Estate’s Journey to Heritage Recognition

by Angela Black*

Nestled on the Northern bank of the Waitematā Harbour is one of Auckland’s most iconic landmarks. Protruding loudly from the native bush and regenerating forest of the surrounding Chelsea Heritage Park, the large, questionably-coloured buildings which make up the Chelsea Sugar Refinery in Birkenhead are hard to miss from its seaward side. Everyday, they serve as a stark reminder to the thousands of commuters and day-trippers who cross the Harbour and residents of the adjacent beaches of Herne Bay that the North Shore, known for its ever-expanding low-rise suburbs and idyllic East Coast bays, is also responsible for producing one of New Zealand’s most-loved commodities: Chelsea Sugar. Indeed, today, the sugar works produces and distributes more than 160,000 tonnes of sugar per year to kitchens throughout New Zealand.

Chelsea Sugar Refinery, Birkenhead, as viewed from the Waitematā Harbour. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0116.

Chelsea Sugar Refinery from Northcote Point. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0126.

Perhaps less well-known than the existence of the iconic factory and its associated brand is the collective anxiety which tore through Birkenhead residents, district councils and local boards alike towards the beginning of the twenty-first century, when the future of the Chelsea factory’s place in Birkenhead was seemingly (albeit, apparently not actually) at risk. In 2006, the owners of the factory, the New Zealand Sugar Company, incited public outcry when they submitted a proposal to the North Shore City Council for the rezoning of Chelsea’s land for residential purposes. The proposed plan, if passed, could allow up to 528 homes to be built on the Chelsea Estate. Fearing that this rezoning marked the beginning of the end of Chelsea’s place in Birkenhead, over 500 submissions were sent to the North Shore City Council opposing the proposed plan.

Article from the North Shore Times inviting submissions about the future of Chelsea Sugar Refining land. North Shore Times, September 15 2006.

What’s most interesting about this large-scale opposition is that the apprehension does not seem to have stemmed from a fear of losing the actual Chelsea sugar brand. Instead, the apprehension stemmed largely from a fear of the brand’s relocation to a new site, and the possible tarnishing which residential activities might have on the existing factory and park in Birkenhead. But if Chelsea sugar – the actual physical output created by the factory – was not at risk, why were we working so hard to protect the mere building in which it began and its surrounding landscape? The answer is, of course, multifaceted but some of its prongs can be deciphered from an examination of submissions against rezoning as well as the report commissioned by Heritage New Zealand upon recognising Chelsea Sugar Refinery and Estate as a Category I Heritage Site in 2009.

To be sure, many of the submissions carried with them concerns typically associated with most plans to drastically increase the number of residential units in an area. One commonly cited worry was increased congestion if residential development of the land ever went ahead. “What happens when they get to Onewa Road?”, one resident asked at a meeting run by the Birkenhead-Northcote Community Board. Another resident, by the name of Wilton Willis, piped in with a claim that this road was already “blocked solid for hours at a time”.

Another group of submissions came in the form of environmental concerns. The Chelsea Heritage Park Association (CHEPA), which had formed in 1997, was especially concerned about the impacts such development would have on the native flora and fauna which lived in the lakes, regenerating forests and wetlands in the 52 hectares of land which made up the surrounding Chelsea Estate.

However, the most interesting group of submissions for our purposes came from those who recognised the historical value of the factory; for 138 years this iconic building has acted as a space of work and leisure, shaping the lives of both its workers and the wider Birkenhead community. It also had connections with broader social movement during the twentieth century. These ideas will be the focus of this essay series but a brief history of the works and some of the other historical values attached to the site by Heritage New Zealand is necessary context to the rest of this series.

The factory itself was opened in 1884 by a conglomerate made up of the Australian Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR), Victoria Sugar Company and a group of Auckland businessmen. Together, this conglomerate formed the short-lived original New Zealand Sugar Company (NZSC), which re-amalgamated into its parent company, CSR, in the face of a collapsing global sugar market in 1887. In 1883, assisted by a New Zealand government bounty offer for the first locally-refined sugar, NZSC bought 160 acres of farmland at Duck Creek near Birkenhead. The site was ideal for a sugar refinery. The creek could be dammed to provide the refinery with all the water needed for its operations. The Waitematā Harbour was deep enough to allow huge cargo ships carrying raw sugar to dock and unload at a wharf. Furthermore, CSR benefitted from the development of a refinery in New Zealand, which was closer to its newly-developed sugar plantations in Fiji.

The restructuring of the land and the building of the refinery began in March 1883 and the finished refinery opened in September 1884. Many of the workers building the factory migrated from Auckland, taking up residence during the winter of 1883 in tents and shacks pitched on the refinery estate. In 1884, NZSC replaced the tents with Chelsea village, which consisted of thirty-five workers’ cottages, a day school, an Anglican church and an independent store. This village was the home of many sugar workers until 1905, when the village was removed following an inadequate health inspection. Several houses from the village were relocated to Birkenhead, where they still stand today. On the site of the old village, the company built four brick duplex houses in 1909 for core tradesmen. These houses are still upright in their original location today.

Before the creation of Chelsea village in 1884, tents were pitched on refinery land as accommodation for men building the factory. These tents can be seen in the foreground of this photo and the half-built refinery is visible in the background. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0137.

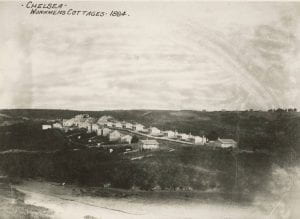

The thirty-five cottages which make up Chelsea village, pictured in 1884 before the construction of the school, church or independent store. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0086.

The four brick duplex houses built in 1909 to house core tradesmen after Chelsea village was removed. This picture was taken in 1910 but the houses are still standing on their original site today. Auckland Library Heritage Collections B0063.

Today, Chelsea Sugar Factory and Estate remains the only sugar refinery in New Zealand and is one of only three nineteenth-century Australasian sugar refineries still operating. Other than a small six-week period in 1920 during which the factory closed due to a workers’ strike, the refinery has been operating non-stop 24 hours a day since it first opened in 1884.

In 2009, partly in response to North Shore City Council granting the proposed rezoning of land on which Chelsea factory stands, the Chelsea Sugar Refinery and Estate was officially designated as a Category 1 Historic Place by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (NZHPT). This recognises Chelsea as a place of ‘special or outstanding historical or cultural heritage significance or value’. Although this designation is the highest level of recognition a site can be given, it does not guarantee Chelsea any legal protection from future development. What it does do is require that the NZHPT be notified of any changes to district plans which may affect the site, ensuring the organisation becomes involved in any decision-making. As a result of this process, full account is taken of the heritage values associated with the site.

NZHPT has already done significant work in assessing the historical and heritage values of the site. In determining the Estate’s place on the Register of Historic Places, the organisation assessed Chelsea against nine “significance criteria”. Its subsequent report established that Chelsea met seven of these criteria, having been deemed significant for its aesthetic, archaeological, architectural, cultural, historical, social and technological values.

However, there is always more work to be done. My hope in this essay series is to further examine the way in which this iconic landmark has shaped the lives and experiences of individuals over the last 138 years, in order to uncover why so many people hold the building and estate dear to their hearts. I will do this through exploring three aspects of Chelsea’s history: its contribution to the development of the suburb of Birkenhead, the relationship which the Birkenhead Sugar Works Employees’ Union had with the wider labour movement, and the human face of the factory, focusing on the everyday lives and experiences of individual Chelsea sugar workers.