Part Two

The Shaping of a Suburb: Chelsea Sugar Factory’s Influence on the Creation of Birkenhead’s Own Unique Identity

by Angela Black*

According to the latest New Zealand national census taken in 2018, Birkenhead township is home to over 10,000 residents. This bustling suburb located just up the hill from the Chelsea estate now boasts two primary schools, a shopping centre, several churches, an award-winning library and a busy wharf, where ferries regularly dock to load and unload people travelling between Birkenhead and Auckland City. But naturally Birkenhead has not always been the buzzing suburb it is today. Indeed, a New Zealand Herald article surveying the outskirts of Auckland in 1913 noted how 50 years prior, in the 1860s, “Northcote and Birkenhead were neglected areas, largely covered with bush and scrub”.

So how did Birkenhead transform from this neglected bushland into a fully-fledged suburb with its own unique identity? By comparing the development of Birkenhead before and after the establishment of Chelsea on its shores in the 1880s, it becomes clear that Birkenhead owes itself greatly to the opening of the Chelsea Sugar Factory. In the words of one sugar worker, “if it was not for [Chelsea], Birkenhead would not have developed for another 20 or 30 years”.

Birkenhead Wharf in 1958. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 998-01.

People and vehicles waiting to board the ferry at Birkenhead wharf in the 1960s. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 998-03.

Birkenhead Public Library pictured in 1985. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0315.

BIRKENHEAD BEFORE THE 1880s

Until the mid-to-late nineteenth century, much of the land which we now know as Birkenhead remained largely uninhabited by Māori and Pākehā alike. To be sure, Te Kawerau ā Maki, whose rohe spans from the Waitakere Ranges up to the Kaipara Harbour in the west as well as across to Mahurangi and down to Takapuna in the east, whakapapa back to this land. In the eighteenth century, they set up small fishing villages on its coastline in order to capture sharks from the Waitematā Harbour. However, these fishing villages remained temporary and few members of Te Kawerau ever sought to inhabit the steep terrain and rugged bush further inland. The soil here was no comparison for growing kumara to that further east near Pupuke, and the denser bush in the Waitakeres to the west provided greater shelter and security for the building of pā. In the 1830s, when the first Pākehā missionaries and explorers came into the Waitematā much of the Birkenhead area was seemingly empty.

In 1841, the New Zealand government purchased the Birkenhead region as part of the sale of a large parcel of land known as the Mahurangi Block. In the ensuing forty years, a handful of Pākehā endeavoured to settle on this land, albeit to varying degrees of success. In 1856, Major Collings de Jersey Grut acquired part of the block of land at Wawaroa Point (this was later to become part of the Chelsea Estate). There he built two solid houses out of nearby kauri for his family and attempted to farm the land. But after numerous problems with their workers, a falling out with their business partner and the death of their two-year-old daughter in a controlled tea-tree fire, the de Grut’s left their property and moved to Orewa.

More successful in his endeavours was Henry Hawkins, who bought a block of land near what was to become Birkenhead Avenue and proceeded to establish himself as the first Pākehā to successfully grow fruit trees in Birkenhead. Setting up several orchards and supplying fruit to Auckland markets, Hawkins became well known throughout the Auckland region. In March 1860, the Auckland Horticultural Society reported on its latest horticultural show in the New Zealander: “The largest display of the finest and most generally acceptable of all fruits […] was made by an old typographer, Mr Hawkins, of the North Shore”. Perhaps even more instrumentally, Hawkins demonstrated that it was possible to settle on the rugged terrain of Birkenhead. In the ensuing years, a few other settlers joined Hawkins, enduring the arduous task of clearing bush and building homes to set up farms and gardens in the vicinity.

Frank Stewart standing in his orchard outside his home in Birkdale. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0447.

Despite this scattering of orchardists in the region leading into the 1860s, Birkenhead was still far from developing its own sense of identity. Indeed, although the name Birkenhead was probably first used in 1863 when land surveyor Charles Heaphy surveyed the land and divided it into lots, it was rarely identified as its own place. Prior to the 1870s, there was no village centre, church, school or public wharf. Settlers after a pub, a church or a ferry boat ride to Auckland City would have to take the difficult bush track to Stokes Point. For stores or markets, they would go even further afield, travelling into Auckland.

CREATION OF CHELSEA VILLAGE

Much of the development of Birkenhead into its own place with a unique sense of identity came from the opening of the Chelsea Sugar Works in September 1884. In 1884, the New Zealand Herald had described settlements in Birkenhead prior to 1884 as “wild and bleak”, with probably only a few hundred people living on the land. The sugar works ushered in families and money. Although a few of the one hundred and fifty workers who built the factory were already locals, most migrated from Auckland City. When the refinery opened in September 1884, one hundred of these workers set up permanently at Chelsea village or up the hill in Birkenhead to continue on operating the factory. By 1886, the population had increased nearly 5-fold, with 334 residents living in Birkenhead town and nearly 200 workers living in Chelsea village. Two years later, in 1888, the population applied to become a borough under the Municipal Corporations Act 1886. To be granted, Birkenhead had to be “an area not more than 9 square miles having no points more than 6 miles distant from one another and having a population of not less than 1000”. On April 11 1888, the Birkenhead Borough Council came into existence. For the first time, Birkenhead was to be recognised as its own independent township.

To be sure, in its early years Birkenhead developed largely independently from Chelsea village, where many of the early sugar workers lived. None of the first councillors of the Birkenhead Borough Council were sugar workers, and the Council largely ignored the happenings at Chelsea, focusing its agenda mostly on developing roads in Birkenhead. Meanwhile Chelsea village, where many of the early sugar workers lived, functioned much like a typical self-sufficient company town. As well as housing thirty-five sugar worker families, Chelsea village had its own church with an attached infant school and reading room, as well as a store on site.

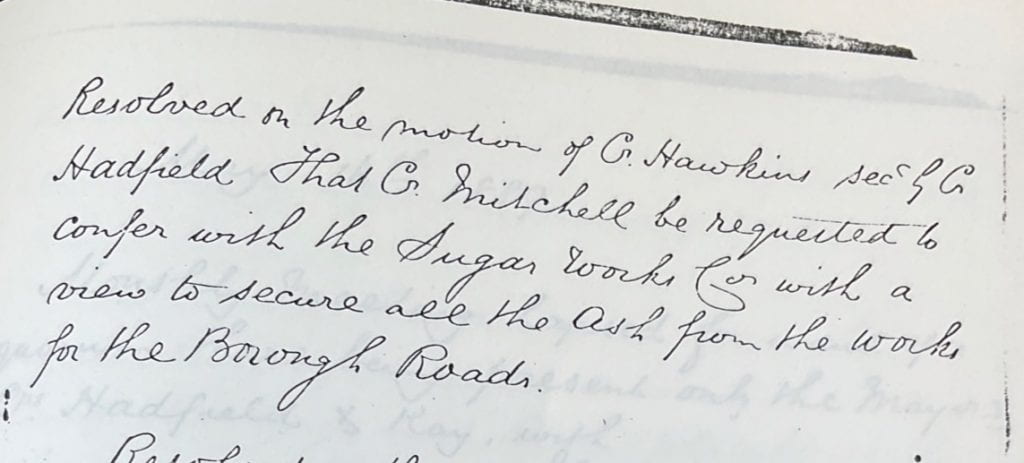

Yet, despite Chelsea’s isolation from the rest of Birkenhead in its initial years of operation, several influential links existed between early Chelsea and Birkenhead. Unlike in the typical company town, Chelsea’s store was independently run, allowing proceeds from Chelsea to fuel out into the wider Birkenhead community. In 1889, further links were established when the Birkenhead Borough Council organised for the ash from the sugar works to be used to build Birkenhead roads. This arrangement continued for nearly 38 years, so that many of Birkenhead’s existing roads today were made with sugar work ash. The Chelsea whistle also became a defining feature of Birkenhead life, acting primarily as a town clock for the residents but also to alert volunteer firefighters of the existence of a fire: one resident remarked how “when the five o’clock whistle blew, the table cloth went on”.

Minutes from the Birkenhead Borough Council Meeting of April 11th, 1889, in which Councillors discussed their plans to use ash from Chelsea to build Birkenhead roads.

BIRKENHEAD AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY

Over the turn of the century, the activities at Chelsea increasingly became amalgamated into Birkenhead life and helped continue to shape the newly-formed borough’s unique character and identity. Crucial to this process was the removal of Chelsea village in 1905 after condemnation by health officials and the subsequent introduction of the Housing Advances for Wage Earners Scheme (H.A.W.E). This scheme involved the Colonial Sugar Company granting its employees housing loans to build family homes in nearby Birkenhead. The process of getting a loan was explained by one worker as follows:

I went to the company and asked them for a loan. They granted me a loan and the maximum was 650. I took 650. I used to have to pay 15/2d a week. They took it out of your pay and that paid principal and interest over twenty-five and a half years. I was earning 3/4/- for a start and they were taking about a quarter. But that was the arrangement. And the interest was only very small, not more than 3%.

The scheme was largely successful, with over 130 houses financed between 1910 and 1926. One worker estimated that three-quarters of the houses in the Birkenhead streets surrounding Chelsea were financed by these loans. Many of these houses still exist in their original spots today.

This amalgamation of sugar workers into the Birkenhead community quickly contributed to Chelsea becoming a mainstay of Birkenhead’s identity. Sugar workers were everywhere, making up over one-third of the men in Birkenhead in 1900, and actively participating in local affairs. Some, like Charlie Castleton, took up posts as Councillors on the Birkenhead Borough Council. Others were instrumental to setting up public amenities; Percy Hurn was a sugar worker but also a member of the committee which opened the Birkenhead Public Library in 1949.

Undoubtedly the most prominent impact Chelsea had on Birkenhead’s sense of identity was through the annual company-sponsored Chelsea picnics. These picnics, which will be discussed in more detail in my final piece, were the highlight of the year for sugar worker and non-sugar worker alike. In the words of one Birkenhead resident:

“The picnics were a real institution in the old days. Pretty well everybody in Birkenhead and Northcote used to pile onto the old ferries and go down the gulf. Practically everybody used to go […], whether they were connected with the sugar-worker or not”.

Birkenhead residents, including Chelsea staff, disembark a ferry at Pine (Herald) Island for the annual Chelsea Sugar Works company picnic. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections T5200.

If we now return to the early 2000s, we can gain a better idea as to why Birkenhead residents were so eager to ensure the refining of Chelsea sugar remained at its original location in Birkenhead. For although outsiders may see the factory as a mere building, the reality is that over the years this factory has been instrumental to the development of Birkenhead as a suburb with its own unique identity. On a wider scale, the history of Chelsea’s place in Birkenhead demonstrates the significance which local landmarks have on defining the spaces they inhabit. For Birkenhead, this economic structure has shaped its identity over the past 138 years.