Part One

CONQUERING THE MAUNGA: Early Encounters with Rangitoto Island

by Blair McIntosh*

Whether it be navigating the Pacific Ocean, scaling Mount Everest or successfully completing the first overland crossing of the South Pole, we as New Zealanders have always liked to imagine ourselves as a hardy nation of voyagers, pioneers and intrepid explorers. Yet for much of Auckland’s early history, it was places and experiences far closer to home which people turned to in order to quench their thirst for adventure. Out of these, none was considered more challenging—or indeed perhaps more worthy of admiration—as a journey to the summit of Rangitoto Island.

Whilst hiking up to the top of Rangitoto might seem tame, even unimpressive by today’s standards, this was not the case 125 years ago. Back then, no track to the summit existed, meaning visitors were without protection when travelling across the Island’s harsh volcanic environment. As anyone who has visited the Island today would likely know, Rangitoto’s crater is flanked by vast scoria fields and ossified lava flows, which due to their exposed position are capable of reaching temperatures exceeding 80°C in the midday sun. Moreover, whilst there is some forest cover on the Island, because the ground underfoot is incredibly sharp and uneven, the chance of serious falls when navigating through dense undergrowth is extremely high. When these conditions are considered, it becomes quickly apparent why successfully reaching the summit without the assistance of tracks was an impressive feat.

Stereoscopic view of Rangitoto, taken in 1918. In the foreground is one of the Island’s numerous scoria fields, that would have to be traversed over in order to reach the summit. Image from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 534-9560.

Indeed, even for early Māori, the summit of Rangitoto has always carried a certain lore. For example, in one origin narrative for Rangitoto, the Island’s summit marks the place where two tipuana (giants) occasionally emerge from their underground exile to gaze upon the maunga created when their incessant quarrelling caused Mataaho, the god of earthquakes and volcanoes, to erupt and destroy their home. In another oral history, Rangitoto’s summit is said to be guarded by two guardian lizards or ngarara once owned by the great Te Arawa explorer Kahumatamomoe. After successfully vindicating his father’s defeat at the hands of Chief Hoturoa (ancestor of the Tanui people) when the two tribes fought at Islington bay, Kahumatamomoe commanded the lizards to protect his land from those who might seek to unrightfully claim it as their own.

SUCCESSFULLY SCALING “OLD RANGI”

The first recorded Pakeha ascent of Rangitoto was completed in 1840 by a little-known lieutenant simply referred to in sources as ‘R.N. Dando’. It appears that the officer secretly made his journey up the slopes of the maunga whilst his warship was moored at Islington Bay (back then more commonly referred to as Drunken Bay, because ships often anchored here while sobering up their crews). However, within the space of a year, several more high-profile attempts to scale Rangitoto were attempted. These included one effort by a rather-eccentric Colonel Branbury, who ran Auckland’s first formal infantry battalion, alongside another attempt by Mr Felton Matthew (the Surveyor General for New Zealand), his wife Sarah Matthew and Auckland’s first Harbourmaster, popularly referred to as “Captain Rough”. According to Sarah Matthew’s diary, the hike to the summit:

“took more than three hours…the heat was excessive and not a drop of water was to be found all day…. The sharp rocks and scoria had worn my boots to pieces and the dress of my merino was torn to shreds, struggling through the thorny bush wood, and the sharp edges of the rocks. Thankful was I to see the shore and the boat at last.”

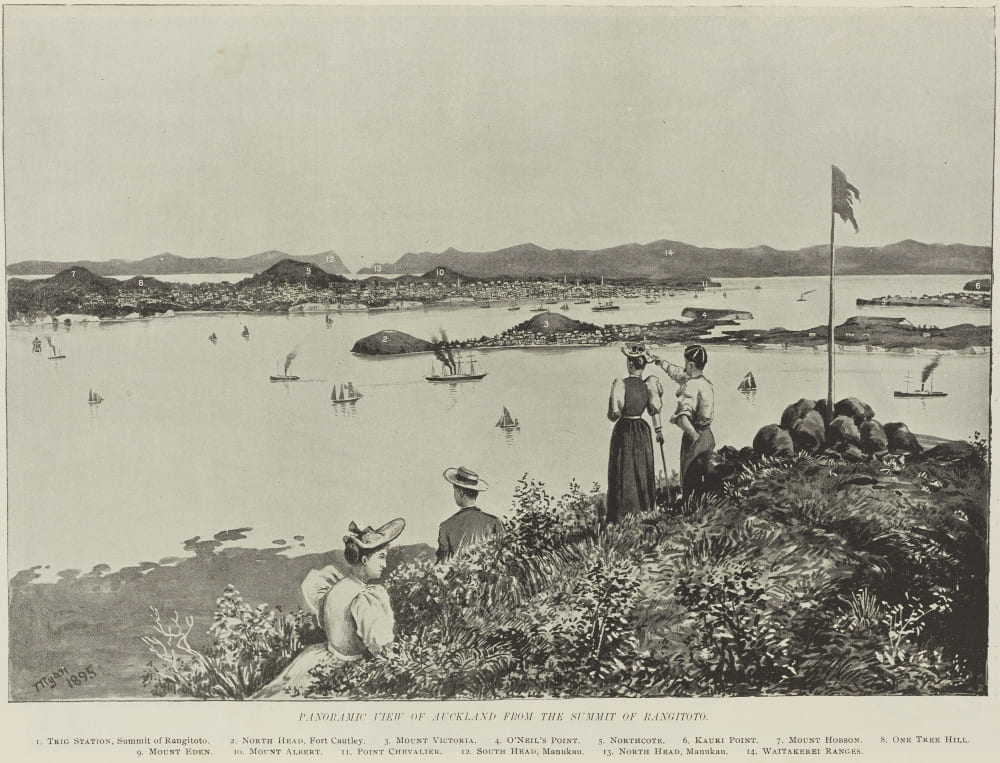

Panoramic view of Auckland from the summit of Rangitoto, published in the New Zealand Geographic on December 18, 1895. Commanding views over Auckland like this were a key factor for impelling many early Pākehā settlers to try and scale the maunga’s heights. Image from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection, NZG-18951218-3-1.

New Zealand’s first recipient of the Victoria Cross, Charles Heaphy, rounded out the list of early Pākehā “explorers” keen to climb Rangitoto, scaling its slopes in 1841 to establish a trig station at the summit under the orders of Mr Matthew. During his ascent, Heaphy also completed a number of sketches of the Island, which would form the basis of his popular series of Auckland watercolours that were widely reproduced in the press for an eager public. Interestingly enough, despite Heaphy’s watercolours clearly capturing the long-standing use of the Rangitoto Island by Māori as a place of economic sustenance and livelihood (see my next essay for more information), many Pākehā continued to depict the Island as a place “totally unexplored”.

Extinct Rangitoto, a set of two watercolours painted by Charles Heaphy in 1859 based on sketches taken during his first ascent of the maunga in 1841. A Maori fishing camp can be seen in the left watercolour. Images from National Library, reference C-025-001 and C-025-002.

Crucially, the timing of these early expeditions to ’conquer’ Rangitoto’s summit were not inconsequential. The colonial province of Auckland itself was only established in 1840, after protracted discussions with iwi following local signings of the Treaty of Waitangi in June. From a strictly practical perspective, in a time before aerial photography, Rangitoto was one of the only places settlers could scale in order to get a comprehensive view of land and seascape surrounding their new settle

ment. However, it was also one of the only places settlers could scale in order to see their new land, an act which allowed them to finally witness the ‘Auckland’ they saw themselves as collectively engaged in building. In this way, the first attempts by Pākehā settlers to reach the summit of Rangitoto can be considered as not just placing Rangitoto onto the map of naval-gazing Aucklanders, but any sense of ‘Auckland’ as a future city too. And with Victoria Cross recipients, colonels, mariners and even rumours of famed Arctic explorer John Franklin’s wife among the few Pākehā who had seemed capable enough to prevail on its shores, the association between Rangitoto and danger, adventure or the chance to play ‘explorer’ was only just beginning.

THE RISE OF THE RANGITOTO ADVENTURE STORY

Between 1860-1880, the tale surrounding the ascent of Rangitoto continued to grow. Particularly with the introduction of extensive waterway networks throughout the Hauraki Gulf, the Island became more accessible to a wider array of Aucklanders, causing the number of excursionists intent on exploring the Island to increase. Yet with the continued absence of any summit track, the ascent to the top was just as arduous as any those undertaken shortly after Auckland’s founding. Thus, while it was not possible to claim being among the ‘first’ to scale Rangitoto, the ascent did still carry with it in the 1860’s-1880’s a certain prestige. Indeed, one paper went so far as to assert that the “undertaking…is looked upon in Auckland social circles as sufficient to entitle the performers to the order of the Star of India [awarded for chivalry], or any other trifle of that kind”. Consequently, it is no wonder that there was no end to those eager to attempt the feat — or make the outcomes of their ‘adventurous exploits’ publicly known.

Particularly in local papers like the New Zealand Herald, Auckland Star and Daily Southern Cross, elaborate stories retelling attempts to scale Rangitoto were soon being published on a near-monthly basis. Rather than being consigned to irrelevant back-page news, many of these recounts were feature articles that read more like modern-day adventure sagas, some even stretching over 3000 words in length. Indeed, an ‘adventure saga is probably an apt descriptor for what many of these stories were trying to achieve. For example, take this recount of an attempt to reach the summit in 1869, written by a reporter for the Daily Southern Cross who agreed to join a hiking party formed by members of the Auckland Institute (now Auckland War Memorial Museum):

“We rapidly pushed ahead, but found the country getting worse every step we took. Our way was blocked up every few yards by deep holes and chasms, and by precipices many feet high. The bush too began to get most inconveniently in our way. We had to force every step through it. The scoria became more and more dangerous, rising and falling rapidly. At one minute we were at the top of a lull, the next we were crawling along a gully choked up with undergrowth. It would be almost impossible to describe accurately the character of the ground. It put me very much in mind of an ice-field suddenly broken up, and jumbled together. The crust, which varied in thickness from an inch to many feet, was forced aside in every conceivable direction. It was exceedingly brittle, and often gave way at the touch of the foot, so that we had many severe falls. In places we came upon the front a precipice thirty or forty feet high, when nothing remained for it but to drag ourselves up by trees and roots, as best we could”.

Danger, if accounts like these are to be believed, seemingly lurked around every corner for the would-be adventurer intent on scaling Rangitoto’s lofty heights. Yet it appears that women rather than men were often more determined to do the conquering. In almost every recorded attempt to ascend Rangitoto reported, women make up a substantial portion of the hiking party assembled. Moreover, despite having to complete the trek in full-length petticoats and blouses, it seems that many were triumphant in reaching the summit – often much to the surprise of their male co-travellers. As one male author of the first known attempt to spend the night on Rangitoto’s summit conceded:

“To our astonishment we found that four ladies had chosen to cast in their lot with the fortunes of the party … determined to see for themselves whether the difficulties and dangers were so great as had been represented, and whether they could not achieve the victory which the late scientific party failed to gain. In fact, this seemed to be the grand motive power which kept their spirits up to the last, and the hope of being able to crow over the professors gave them an unnatural strength, which carried them, as will be seen, in triumph to the end of the arduous undertaking”.

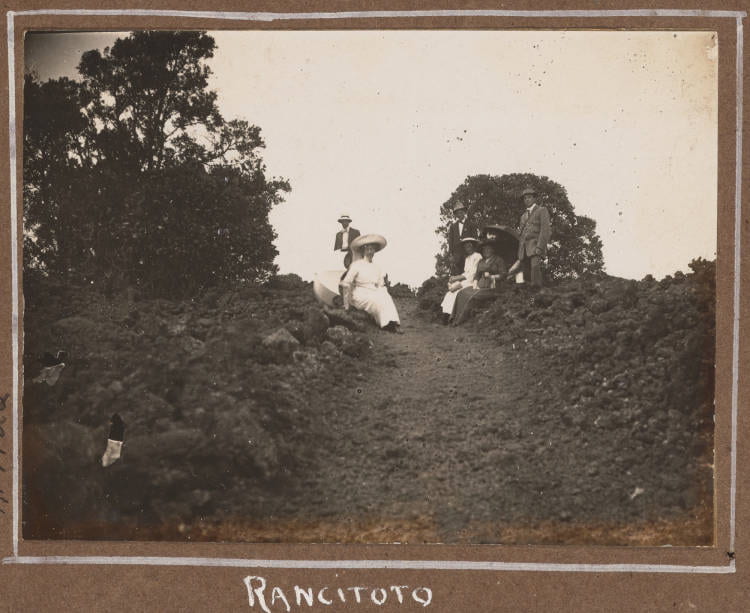

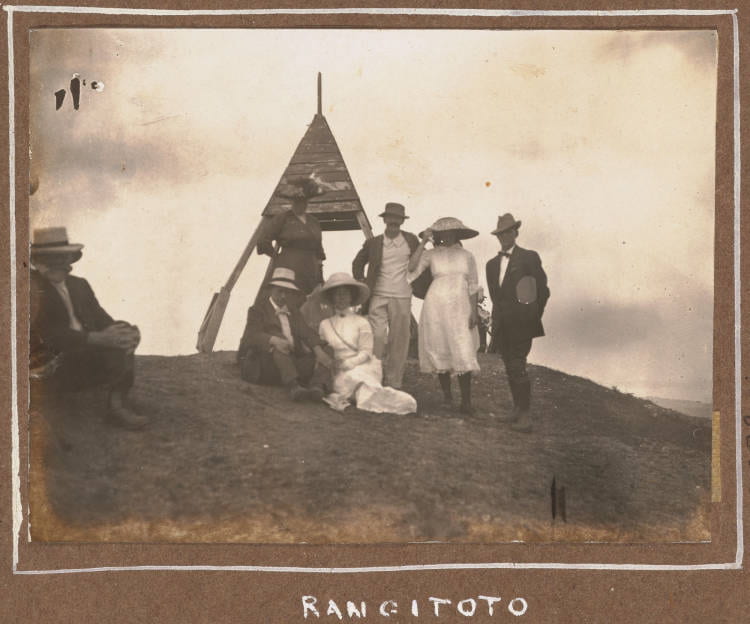

Photographs taken of a successful summit party, date unknown. It is worth noting that despite women making up a significant number of those who climbed Rangitoto (and are featured in these photos), nearly all accounts published in the local newspapers were written by men. Images from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 499-ALB116F-13-05 and 499-ALB116F-17-06.

As the historian Adriana Craciun has argued, exploration in the late-nineteenth century was fundamentally about performance: one was not born as an ‘explorer’ but became an explorer, often in interaction with prevailing ideas of geographic discovery circulating at the time. Whilst it is fair to say that climbing a volcanic cone in Auckland doesn’t quite compare to trekking across the Sahara, reaching the South Pole or navigating the Amazon River, it was nevertheless a place which challenged Aucklanders in ways which caused them to imagine Rangitoto as being out there, in that part of the world only frequented by the bold and daring. By locating the Island on the very edge of Auckland’s imagined frontier, it allowed many of these ‘Rangitoto adventure’ authors to stylise themselves as authentically being—even if only for a brief moment—fully-fledged ‘explorers’.

THE END OR BEGINNING OF EXPLORING RANGITOTO?

On November 3rd 1896, more than 2,500 Aucklanders took the ferry across to Rangitoto to witness a momentous occasion: the grand opening of the Island’s first walkway to the summit, portentously called the ‘Pioneer Track’. After a series of speeches by important local dignitaries and several musical contributions by the Auckland Garrison Band, the wide, smooth track was cast open for the public to eagerly enjoy, now able to ascend the maunga that had for so long been regarded as only fit for the most daring of individuals. Unsurprisingly, the installation of the track had many who had once spent a great deal of time and effort publicising their attempts to reach the summit rather despondent. As one former author of an 1888 summit attempt in the Auckland Star bemoaned:

“No longer will the soul of the bold adventurer who scales Rangitoto’s triple peaks be made aweary, and his shoe leather reduced to shreds by the sharp scoria, ledges and ridges; and no more will the stranger within our gates lament the day that he was beguiled to take a walk up the venerable lava pile in his best clothes. We are to have a comfortable footway to the top of the centre peak, and the elderly lady and small child will be able to say that they have achieved that one-time perilous feat, a climb to the top of Rangitoto…. Really, they are making things too comfortable altogether.”

Although the opening of a track to the crater of Rangitoto may have caused many past travellers to lament the death of the so-called ‘Rangitoto explorer’, the injurious wound, I would argue, was self-inflicted. By publishing their elaborate tales of fantastical exploits across the front pages of local newspapers, these early travellers to Rangitoto seeded amongst their contemporaries not simply an awareness of the Island but an appetite to eventually “discover” it for themselves.

For the majority of those 2,500 Aucklanders who had lobbied the Devonport Borough Council for a walkway to the summit to be installed, and eagerly purchased tickets to attend the Pioneer Track’s grand opening, it was not any prior experience of actually walking on Rangitoto Island that brought them there. Rather, it was the chance to finally visit for themselves that place most Aucklanders already had such a rich imagination about but had never actually scaled; that place which, as one letter to the editor of the New Zealand Herald ruefully remarked, felt now more than ever was ‘so near yet so far’. Perhaps more than any other group of Aucklanders who interacted with the maunga, it was the framings of Rangitoto these self-professed ‘explorers’ put forward—framings of Rangitoto as out there, on Auckland’s imagined frontier—that shaped the assumptions and expectations later visitors to the Rangitoto’s shores envisioned the Island as capable of fulfilling.

As the next essay in this series will reveal, having finally conquered the summit, a new wave of Aucklanders descended on the maunga, energised by the lure of further transforming the unruly maunga into an arcadian promised land of milk and honey.