Part Three

Sanctuary at the Ends of the Earth

by Sarah Oliver*

“The colony of New Zealand had been established on a basis of religious and political freedom. The social and cultural traditions of England were preserved, but any discrimination against any form of religious belief was discarded. From the outset, the Jews shared fully in all the rights and duties of citizenship”

This positive depiction of New Zealand as a sanctuary for Jews was by Violet Balkind in her 1928 Master’s thesis, “A Contribution to the History of the Jews in New Zealand”. In the burgeoning colony of New Zealand, England’s historic discriminatory laws controlling the freedom of religious minority groups, including Catholics and Jews, were not established. Without these laws, Auckland’s Jewish community were able to have full rights in New Zealand, where “every avenue of advancement” was open to them and where their community identity developed “amid conditions of freedom”. But this was not always true for Auckland’s Jewish community, sometimes having to face the ugly head of anti-Semitism at the other side of the world.

Commercial Bay, Auckland, 1840 (Nathan & Joseph’s tent present). Image from S.G. Frith Collection, Auckland City Libraries, Reference 1043-090.

David Nathan, a Jewish merchant successful in trade with Māori, c. 1882. Image from The Observer, June 17, 1882.

Frontier Life

Auckland in the nineteenth century was a frontier settlement of the British Empire to a small minority of immigrants in a land that was still controlled primarily by Māori. The difficulties and hardships faced in a new colonial settlement were shared by all: whichever denomination of Christianity one subscribed to or even which religion, such as Judaism, was considered less important. Colonists bonded by a need to help each other survive, even going so far as to support one another build places of worship. David Nathan was a Jew who followed this precedent and was famous for having “‘a brick’ in every church and chapel in Auckland.”

New Zealand was described as somewhere where “Protestant, Catholic and Jew all meet on equal footing and as the best of friends.” A place, narrated by the 1931 New Zealand Jewish Review, where Jews found “a haven of rest and of refuge from the conflicts and cleavages of the Old World,” enjoying “material prosperity and spiritual contentment.” The Jewish community’s attempt to bring together ten men for public worship (minyan) was supported wholeheartedly by Christian leaders in the town, who cheered their efforts. When the congregation later built their Princes Street Synagogue in 1885, Philip Philips was recorded in the Daily Southern Cross to have “paid a high compliment to the charitable disposition of the Christians of Auckland” for standing by with assistance. Auckland’s Jews were essential to the town’s success, bringing their unique entrepreneurism and business sense. David Nathan’s Orthodox Jewish traits of integrity and trustworthiness gained him success in trade with Māori.

Friendships in Auckland

Auckland was where Jews were welcomed and appreciated by many of the non-Jewish population, with many Jews enjoying friendships and work relations with high-ranking members of the colony. Rabbi Goldstein had notable companions with heads of other churches, including the Anglican Bishop, and with his neighbour, Governor, Sir George Grey. After Grey’s death, Goldstein presided over the committee assigned to erect a statue of his friend and former Governor. Goldstein’s extensive knowledge of Hebrew was not reserved for the Jewish congregation, but also accessed by Christian theological students. On his eightieth birthday, he was paid a tribute by Dr Ranston, the Trinity Methodist College principal, for sharing his knowledge.

Similarly, the Jewish Keesing family had a good friendship with their neighbour, Governor Grey, who was inspired to learn Hebrew after visiting the family, showing a strong appreciation for Jewish culture by the highest-ranking official in the new colony. James Sharland, a Jewish chemist, enjoyed great success in his trade in the new colony, being the chemist to successive governors of New Zealand. Philip Aaron Philips was Jewish and the first mayor of Auckland and was instrumental in claiming the old army barracks as parkland, constructing Albert Park for Aucklanders. His actions were commemorated by a park plaque that depicts a Star of David, a symbol of Judaism, openly alongside his name, showing an acceptance by Aucklanders of his religion. David Nathan also displayed the Jewish Star of David openly as his business logo, another example of Jewishness being portrayed in the public life of Auckland. Members of the Jewish community were embraced and appreciated by many non-Jews in Auckland, lacking a stigma against them due to their religion as they experienced in their home country of England.

Statue of Sir George Grey, Albert Park (Rabbi Goldstein was president of committee for the erection of this statue), February 28, 2022. Image taken by Sarah Oliver.

Political Emancipation for English Jews

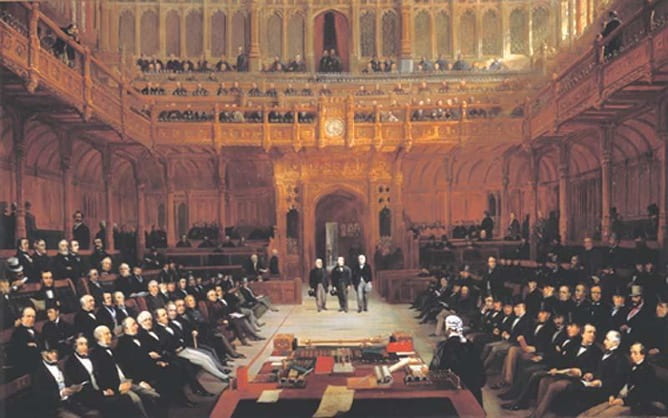

Many of the nineteenth-century Jewish immigrants to Auckland came from England, where they experienced unequal rights in civic and political participation. Finestein (1959-61) claimed that only ten years before David Nathan and other Jewish merchants came to New Zealand to set up businesses, Jews were not legally able to carry out retail trade in London until 1830. Finestein further stated that not until 1845 were Jews able to stand for municipal office, although Auckland’s first mayor was Jewish, Philip A. Philips. New Zealand, like other British colonies, was establishing in the middle nineteenth-century at a time when political opinion and thinking was “characterized by liberal concepts averse to legal discrimination for reasons of religion.” In Britain at this same time, a compulsory oath of loyalty to the Church of England and the request to take an oath on the Christian bible, barred Jews from taking office without converting to Christianity first. Lionel Nathan Rothschild and David Salomons struggled to take their seats in English parliament in the 1840s and 1850s, Rothschild refusing the oath.

Although the struggle affected a community and parliament on the other side of the world, Auckland’s Jews were still strongly connected with England and so “followed … with interest, the long struggle for political emancipation among their brethren”. After decades of campaigning, the 1858 Jewish Relief Act was passed, which allowed the entrance of Jews to the House of Commons by dispensing with the Christian wording of the oath. In Auckland, the Act was greeted with “great rejoicing among the Jews of New Zealand”. The Auckland Congregation held a special service at the Synagogue, forwarded a letter of congratulations to English Jews, and held a great celebration at the Auckland Masonic Hall on Princes Street.

Henry Barraud, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1808–1879) introduced in the House of Commons on 26 July 1858 by Lord John Russell and Mr Abel Smith, 1872, oil on canvas, The Rothschild Archive Online, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lionel_de_Rothschild_HOC.jpg.

Anti-Semitism in the New Colony

Auckland in the nineteenth century appeared to be a sanctuary from the Old World discrimination for Jews. But this was not always so; when Philip A. Philips, a prominent member of the Jewish community, became mayor in 1871, this produced anti-Semitic sentiment in the new colony. In the Auckland Star on December 18th, 1871, a Mr George Staines was reported to have unleashed vile remarks towards Philips in a public meeting in Auckland, labelled “The Monster (!) Meeting”. Calling him a “mean, despicable Jew” and asking the crowd if they will let “a low mean, needy Jew be Mayor over you?” He continued his speech, stating: “You’re all afraid of these Jews, they rule over you, but I’m not afraid of any of ’em,” and escalating his comments, stated: “I likes my beer, but I hates a Jew.” Staines was hedged on in his speech by the crowd who were reported to have told him to, “Go it Staines,” and Give it them, George.” The newspaper did not so favour the words of Staines by starting its article with an apology for the offensive subject matter. A newspaper commentator stated Mr Staines had undertaken a “vicious and scoundrelly attack on an inoffensive and respectable section of the community [the Jews]” and that his views did not represent the views of a majority of people and had “excited as much disgust”. A similar article in the Thames Guardian and Mining Record was ended by labelling Staines meeting as “the most disgraceful in the whole history of Auckland’s political gatherings.”

Article Headline of Mr. Staines Meeting in the Auckland Star, December 18th, 1871.

Jews were welcomed to the colonial town of Auckland and appeared, on the whole, to be accepted. Still, Jews never immigrated in large numbers, staying as a small percentage of the population, only 0.6% in 1867. The possible immigration of five-hundred Russian Jews to New Zealand to escape persecution in Russia was met by protest in 1893, showing an uneasiness by New Zealanders to accept Jews. An 1893 Auckland Star article depicted a strong anti-Semitic sentiment among Auckland. It claimed, “No one who has seen the Jew in Russia can wonder that they want to get rid of a creature is so clannish and so dirty, who is so entirely bent on making a little money simply for himself.” Another letter-writer to the Auckland Star claimed he failed “to see why so much fear and agitation should be displayed” by the immigration of “a paltry 400”, claiming that their religion did not stop them “becoming law abiding citizens and good colonists”. Auckland’s non-Jewish population widely accepted Henry Keesing’s English Jewish counterparts in Auckland. Still, he was “not yet have been accepted as an equal by Anglo-Saxon neighbours, his Jewish religion and his Dutch accent counting against him”. Being Jewish and Dutch made him not accepted in Auckland’s social scene. It seems that Aucklanders welcomed the home-grown English Jewish population, but immigration of non-British European Jews brought fear and anxiety to the forefront for many. However, others still strove for a “universal brotherhood.”

Legally and politically, Auckland was a sanctuary from religious discrimination for Auckland’s Jewish community, who landed on these shores in the nineteenth century. England’s historic discriminatory laws against religious minority groups, which were not rebuked until 1858, did not occur in New Zealand. The social reality was not as clear, although Jews made many friends in the colony and were openly appreciated and supported in setting up a community. Newspaper articles from the time show that Auckland’s Jewish community still experienced anti-Semitism in Auckland. However, the overall image presented by Violet Balkind is of a town where they embraced religious sanctuary, and Jews prospered.

* Sarah would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jewish Lives in her research (www.jewishlives.nz)