Part Four

Conserving Auckland’s Nineteenth Century Built Jewish Heritage

Part Three

Sanctuary at the Ends of the Earth

by Sarah Oliver*

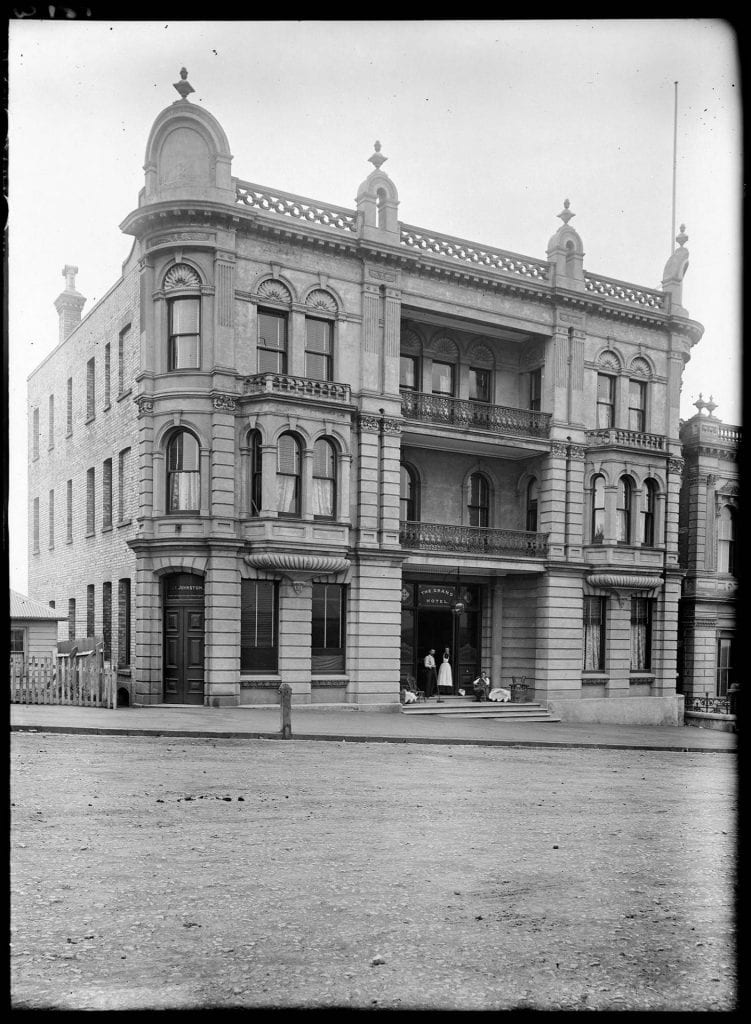

In previous essays, I have examined the setting-up of a religious community in colonial Auckland, the lives of nineteenth-century Jews who lived in Princes Street and Waterloo Quadrant, and their experience of a religious sanctuary. All these histories I have explored through the built heritage of a minority group of Auckland – the Princes Street merchant houses, the house of David Nathan (16 Waterloo Quadrant), the Grand Hotel owned by the Davis family, and the Princes Street Synagogue. Heritage management is an important activity done by communities to preserve a physical link with their past. My research is but one example that demonstrates the value of preserving heritage sites. Conserving and restoring these sites preserves a physical trace of the central Auckland Jewish community in the nineteenth century, an important part of Auckland’s history.

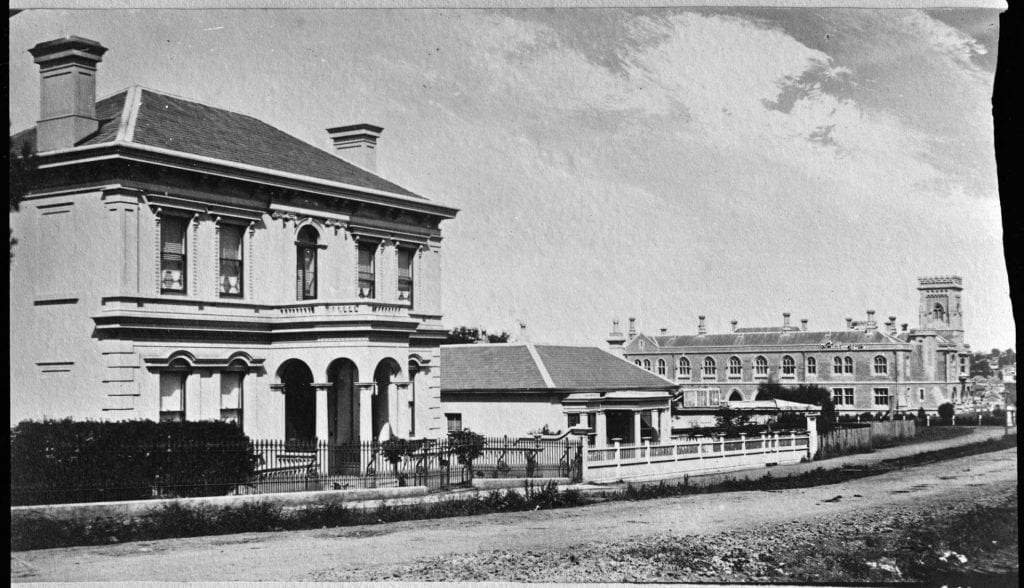

Princes Street, 1880 (the merchant houses are on the right, note that the site where the future Synagogue was to be built is empty). Image from Alexander Turnbull Library, Reference 1/2-029170-F.

Princes Street Merchant Houses on the ridge above the downtown business district. Image from Henry Winkelmann Collection, Auckland Council Libraries, Reference 1-W1172.

Princes Street Merchant Houses

The late nineteenth-century Victorian merchant houses on the western side of Princes Street (numbers 21, 23, 25/27, 29, 31), as outlined in my previous essay, were central to the Central Auckland Jewish community’s identity. The houses’ elevated position and proximity to the Princes Street Synagogue that rested on Princes Street and Bowen Avenue, and to the downtown business district, made them desirable homes for successful Auckland Jews. We can see this with prominent members of the Jewish community such as James Sharland, Philip Aaron Philips, Arthur Hyam Nathan, and the Davis family, making them their homes. The land lots’ original advertisement was targeted towards “commercial men” who wanted to secure a site for “villa residences, within five minutes’ walk of their place of business”. By investigating these homes alongside their occupants and their business or public lives they act as a starting point to exploring larger themes, including (as I have done in my previous essay) understanding the identity of the Central Auckland Jewish community. This is a crucial reason why homes such as these and other forms of built heritage should be preserved, in preserving them we preserve an awareness of identity and the dynamic histories of Auckland’s minority groups.

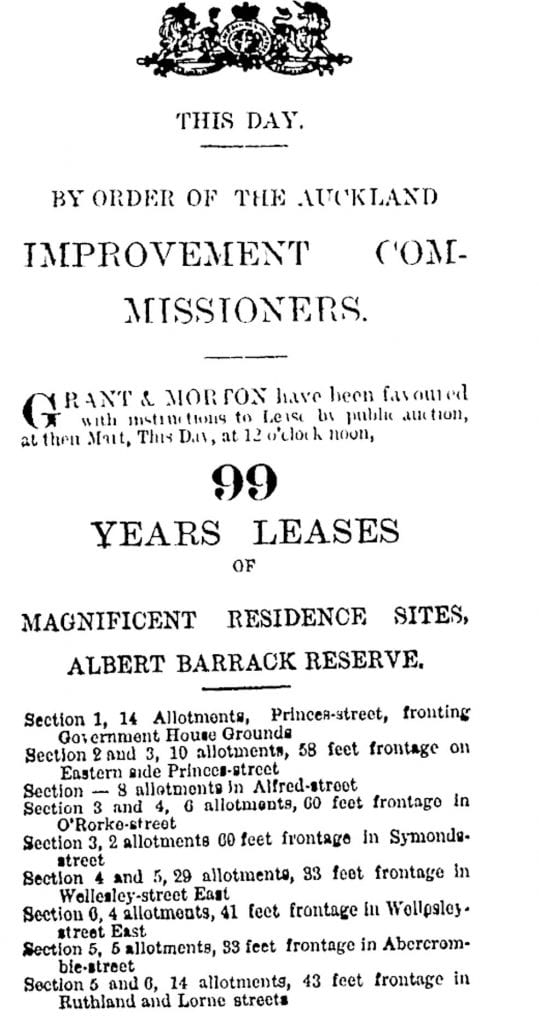

Advertisement in the Daily Southern Cross, December 2nd, 1875, for the lease of the Princes Street land lots.

The land lots on the western side of Princes Street were allocated from the public land of the Albert Barrack Reserve with a limited ninety-nine-year lease by the Auckland Improvement Act of 1872. It was planned that when the leases expired in the 1970s the land’s ownership would revert to the council who would demolish the houses to expand Albert Park. In 1963, the Council decided to go ahead with demolishing the houses. It would have been a great loss to Auckland’s heritage as most of the historic homes in Princes Street and central Auckland had already been demolished, making these some of the last examples of Victorian residential architecture in central Auckland. Growing awareness among Aucklanders of the importance of heritage preservation in the 1970s led to a good result with Auckland Council amending the original 1872 Improvement Act, allowing the houses to be retained. Nola Easdale wrote in her 1980 Hamurana Civic Trust writing Five Gentlemen’s Residences in Princes Street, of how the merchant houses of Princes Street offer a lead into thinking of the lives of their former occupants:

“100 years since the houses were built. Now with their preservation, we today and in the future, perhaps in a leisurely moment as we walk by can reflect on those who once lived there and in imagination repeople Princes Street with their shades.”

Princes Street Merchant Houses’ Plaque. Image taken by Sarah Oliver, Date: 28/02/2022.

Princes Street Synagogue

The Princes Street Synagogue on the corner of Princes Street and Bowen Avenue was the “spiritual heart” of the Jewish community for 84 years from its consecration in 1885 until the congregation outgrew it and moved into a larger building in Grey’s Avenue in 1968. It was quoted in its conservation plan to be a “rare example of Jewish ecclesiastical architectures”, being only one of two surviving nineteenth-century synagogues in New Zealand, and it was of “prime importance” that it was protected. It stands to show that “the strength of the Jewish community in Auckland City” and “the success of many of its adherents in the colony”, as after only forty years of colonial settlements the community was able to build this magnificent building. Heritage New Zealand stated that “its prominent location appears to be unusual, reflecting a degree of confidence not found in all parts of the Jewish diaspora.” The Synagogue acts as a strong visual and physical reminder of the central Auckland Jewish community.

Princes Street Synagogue, 1885. Image from Te Papa Collection, Reference Burton Brothers studio C.010946.

The former Synagogue, c.1988 (during its time of decay). Image from Auckland Museum Collection, Reference PH-2015-2-GH2235-36A.

Former Synagogue, 28/02/2022. Image taken by Sarah Oliver.

In 1969, when the building was retired from being a Synagogue, its ownership reverted to the Auckland City Council. For the next twenty years it “suffered severe neglect and consequent decay,” until a trust amendment in 1985 allowed the Council to lease the premises for commercial interest. Salmond Reed Architects were then employed to meticulously restore the Grade 1 listed historic building and convert it into offices for a branch of the National Bank. This restoration spanned from employing decorative artists to redo ornate stenciling, and undertaking extensive structural and strengthening work. The restoration was received well, and won multiple architecture awards, including the New Zealand Historic Places Trust Award for Developers, by successfully merging commercial requirements with historic conservation. A decision made in the renovation to create easy access for bank patrons from Princes Street, meant installing a new doorway through what was originally the sanctuary where the Torah scrolls were kept and the spiritual heart of the Synagogue. Although the building is now deconsecrated, the installation of a door for thoroughfare through what was the spiritual heart of the Synagogue can be viewed as questionable, even insensitive to the buildings earlier life as a place of worship. Since 2003 it has been leased to the University of Auckland to house the university’s alumni relations and development office.

The Fate of Heritage – David Nathan’s former home and the Grand Hotel

The home at 16 Waterloo Quadrant was built by David Nathan, a strong Orthodox Jew and one of the first Jews to move to Auckland where his firm gained great success. 16 Waterloo Quadrant was owned by the Auckland Catholic Tertiary Chaplaincy from 1947 (called ‘Newman Hall’), until they sold the building in 2017. Before selling, the Diocese of Auckland drafted an architectural plan to restore the house and build an office block. But it was stopped due to a spring significant to local Māori flowing in the area, Wai Ariki had fed two historic pā sites in the area. They cited seismic issues as the reason for ultimately putting the building up for sale, stating they “were unhappy about the health and safety obligations that they would be under… require insurance and so forth at a level that just was not viable for us”. Historic buildings often face seismic issues due to new stagnant building rules, and it is a common problem for owners, and the conservation of heritage buildings for the general public. The property went on the market in 2016, and its advertisement stated it was a protected historic building, but could “form the entrance to a hotel, residential apartment development or student accommodation,” if they were able to get approval by iwi to build. The new owners have as of February 2021 not restored or built an office block at 16 Waterloo Quadrant.

David Nathan’s Home, 16 Waterloo Quadrant, 1880. Image from Winkelmann Collection, Auckland Council Libraries, Reference 1-W0270.

16 Waterloo Quadrant, 28/02/2022. Image taken by Sarah Oliver.

What is the future for David Nathan’s home at 16 Waterloo Quadrant? Conserving a historic building or its façade to act as an entrance to an office block is a common fate for historic buildings in central Auckland. The Grand Hotel (built in 1899), owned by the Davis Family, is now a façade on Princes Street after the building was demolished in 1987 for the development of a 15-floor office tower. Having large modern office blocks behind historic buildings disrupts the historic streetscape of Central Auckland. Demolishing of buildings such as the Grand Hotel are an even bigger tragedy for conserving our city’s identity, and the history of Auckland’s various immigrant groups. Newman Hall needs restoration work to stand as magnificent a house as it originally was when David Nathan built it. Its owners in 2018 were recorded to have “certain parts of the building they are not allowing anybody in because of the risk of collapse”. The plans of Moller Architects to build an office block also include restoring Newman Hall, “The existing Newman Hall was proposed to be stripped back and divest itself of the accumulated additions and alterations that had sullied the form of the building over a period of time and return it to its former glory.”

The Grand Hotel, Princes Street, 1899. Image from Winkelmann Collection, Auckland Council Libraries, Reference 1-W0137.

The Grand Hotel’s Façade, 28/02/2022. Image taken by Sarah Oliver.

The merchant villas of Princes Street, the former home of David Nathan, the Grand Hotel, and the magnificent Princes Street Synagogue, all speak to the success of early Jews in colonial Auckland. Their preservation, and hopefully in some cases, restoration to their former glory, stand as a memorial to the Jewish community of Central Auckland, and their place in forming the identity of early Auckland. Heritage management is important, but it is especially critical for minority groups whose voices in history are so often marginalised or forgotten. If the nineteenth-century Synagogue in Princes Street acts to remind us of the long history of Auckland’s Jewish community in the city, what then could other heritage sites tell Auckland of other cultural groups? Built heritage is so important for sparking discussions and investigations into Auckland’s past, especially for exploring the community identity of cultural minority groups.

* Sarah would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jewish Lives in her research (www.jewishlives.nz)