Part Two

The Contagious Diseases Act 1869: Immoral, Unequal, or Necessary?

by Saana Judd*

The Auckland Women’s Christian Temperance Union (AWCTU), the Auckland Women’s Political League (AWPL) and the Auckland Women’s Liberal League all campaigned fervently over issues of importance to them, with one being the growing problem of sexually transmitted diseases (then known as venereal disease) in New Zealand. Whilst the goal of all three political groups was to rid the country of these diseases, their positions on how the state should go about doing so were deeply divided. Their opinions on the Contagious Diseases Act 1869 (C.D. Act) – the principal piece of legislation introduced to combat venereal disease – revealed a split in the feminist consciousness of late nineteenth-century Auckland. With the AWCTU and AWPL opposing the Act on the grounds of morality and equality, and the Liberal League supporting it to protect women, the feminist perspective on the C.D. Act was not a straightforward one.

Venereal disease and the Contagious Diseases Act 1869: the state of affairs.

One of the greatest concerns among Auckland women at the turn of the twentieth century was venereal disease. Although no statistical information exists on the number of cases of venereal disease in the country at that time – there was no centralised record system and those infected rarely presented to doctors – the general consensus among historians and contemporary doctors alike was that cases were rising in conjunction with rising population numbers. Together with this increase was growing knowledge about the harmful effects of venereal diseases like syphilis, which became linked with damage to the eyes, liver, and kidney. To make matters worse, medical treatments like mercury and potassium iodide offered for venereal disease were largely ineffective and often harmful. The combination of increasing case numbers and poor treatment options created a large amount of fear in society. Coupled with fear was an increasing sense of moral panic over the prevalence of a disease associated with sexual corruption and prostitution. The desire to contain the spread of the disease and reduce rates of sexual impurity placed the topic of venereal disease at the forefront of the national conscience. To address these issues, the Contagious Diseases Act was passed in parliament on 3 September 1869. This followed the Contagious Diseases Acts passed in Britain in 1864, 1866, and 1869, which were also applied throughout the British Empire.

The Contagious Diseases Act 1869 (C.D. Act) was established as a measure to combat venereal disease and regulate prostitution in New Zealand. Like the British Acts, the police were granted the power to force any woman they believed to be a ‘common prostitute’ to undergo a mandatory vaginal examination. Women found to be carrying venereal disease were sent to a ‘lock’ hospital or gaol where they were detained until they were classed as disease-free. Whilst these terms alone made the Act controversial, the fact that it applied to female prostitutes alone and not their (male) clients was highly contentious.

Once passed by parliament, the C.D. Act was not automatically applied in New Zealand under the central government. Rather, the power to adopt and enforce the Act was left to each provincial government. In the end, it was only Canterbury and Auckland that ever implemented the C.D. Act, with Auckland adopting it in 1882. However, owing to increasing public dissatisfaction, the Act was only actively enforced in Auckland until 1886, the same year the Acts were repealed in Britain. Despite the relatively short period of active implementation in Auckland, the C.D. Act created much debate locally and its continued presence on the statute books right up to 1910 was a point of conflict. Living in one of the only two cities to ever implement the C.D. Act, Aucklanders felt strongly about the impact that it had on women and society. As such, it became a topic of great concern among Auckland women’s political groups. Taking a particularly strong stance on the topic was the Auckland Women’s Christian Temperance Union (AWCTU) and the Auckland Women’s Political League (AWPL), who both opposed the C.D. Act on the grounds of morality and equality.

In favour of repeal: Inequality in the C.D. Act.

The AWPL and the AWCTU insisted that the C.D. Act be repealed on the grounds that it was deeply unequal and unfair to women. Not only was the Act a physical violation of women’s bodily autonomy, but by punishing women alone, the Act reinforced a double standard of morality over the sexual behaviour of men and women. Writing in support of the C.D. Act’s repeal, the AWPL stated that the “one-sidedness of the act” was an “insult to every woman in the colony”. Taking a similar stance, the AWCTU passed a resolution stating that the Act was “obnoxious and degrading” to women, asking for its urgent removal from the statute books. Additionally, the AWPL and the AWCTU both stressed that the inequality of the C.D. Act made it effectively useless as a piece of legislation to prevent the spread of disease. The groups claimed that by only examining women, the Act ignored the fact that venereal disease was often passed on to sex workers through their male clients. Given this inequality, the AWPL asked that “all laws relating to the moral conduct of women should be so altered and framed as to include both sexes”. However, rather than merely amending the C.D. Act, the AWPL stressed that “fresh legislation should be introduced punishing both sexes equally”.

Both the AWPL and the AWCTU undertook many efforts to repeal the C.D. Act on the grounds of gender inequality. The primary method used by both groups was to bombard parliament with petitions asking for the immediate repeal of the C.D. Act. These petitions were heard and supported by the House of Representatives, who passed through multiple bills designed to remove the C.D. Act from the statute books. These bills, however, were repeatedly rejected by the Legislative Council, New Zealand’s Upper House. The constant roadblocking from the Upper House caused much frustration to women’s political groups in Auckland, with the AWPL stating that although “women all over the colony are acting in unison…until our forces are stronger than the men lawmakers there is but little hope for this reform”.

In the meantime, the AWPL and AWCTU undertook other measures to address the inequality present in matters surrounding venereal disease. Specifically, both groups campaigned for equal treatment for women suffering with venereal disease. According to the minute books of the AWPL and the AWCTU, Auckland women were denied treatment when presenting to hospital with symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases, while men were admitted as patients. To combat this, both groups met with the Auckland Hospital and Charitable Aid Board to advocate for women’s rights to equal treatment and ask for a divided wing to be introduced to the hospital to treat both male and female patients with venereal disease. Ultimately, both groups thought it necessary to advocate for equal treatment for the wives of adulterous men who were suffering “through no sin of their own”.

Auckland Hospital, circa 1900. Source: Winkelmann, Henry. “Auckland Hospital, around 1900”. Ref: 1-W123. Sir George Grey Special Collections Auckland City Libraries, Auckland, New Zealand.

In favour of repeal: The C.D. Act as immoral.

The second issue that the AWCTU and AWPL had with the C.D. Act was based on the conviction that prostitution – and therefore any means of regulating it – was morally corrupt. During the late-nineteenth century, Auckland was heavily dominated by Christian values, and prostitution was considered a deeply un-Christian “social evil” that could not be accepted. As such, the AWCTU passionately opposed the C.D. Act, which it considered to be a form of state-sanctioned vice. According to the AWCTU, by attempting to prevent the spread of venereal disease among the sex industry, the State was effectively endorsing prostitution. For the AWCTU – a group committed to the pursuit of social purity as well as women’s rights – the mere existence of the C.D. Act on the statute books, whether implemented or not, posed a threat to Christian morality and “greatly hindered” the Union’s “work of social purity”.

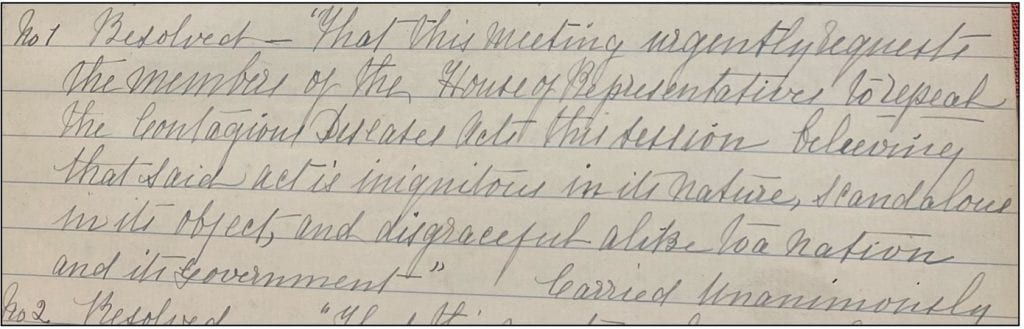

To combat prostitution and advocate for social purity, the AWCTU routinely urged the State to repeal the C.D. Act. The Union sent multiple letters and petitions outlining their position on the subject to governance bodies at local and national levels. In one such letter, the AWCTU sent a resolution to the House of Representatives, Legislative Council and the Charitable Aid Board, stressing that the C.D. Act was “iniquitous in its nature, scandalous in its object, and disgraceful alike to a nation and its government”. As an alternative to the C.D. Act, both the AWCTU and AWPL advocated for the Suppression of Immorality Bill. This bill was designed to prevent prostitution entirely by giving police the power to arrest any person found present in a brothel, regardless of gender.

Beyond efforts to repeal the C.D. Act, the AWCTU’s attitude to prostitution and social purity reform is outlined in its effort to increase the power of the police. The Union passed a resolution asking for more power to be given to police for the “suppression of immoral houses and the arrest and prosecution of those found within” and wrote to an Auckland Councillor urging him to use his influence to “assist the police to stamp…out” the “social evil” in the city. The AWCTU’s religious- and morality-based argument against the C.D. Act is reflected in a New Zealand Herald article encouraging the repeal of the C.D. Act. The author, writing in support of the AWCTU, stated that “Christ’s law of morality is the only one on which a social state can be safely built”, with the C.D. Act being “an insult to the Christian conscience”.

AWCTU minute book: the C.D Act is “iniquitous in nature, scandalous in object, and disgraceful alike to a nation and its Government”. Source: Minute Book – Auckland, 1898-1902, New Zealand Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

In favour of enforcement: the Auckland Women’s Liberal League.

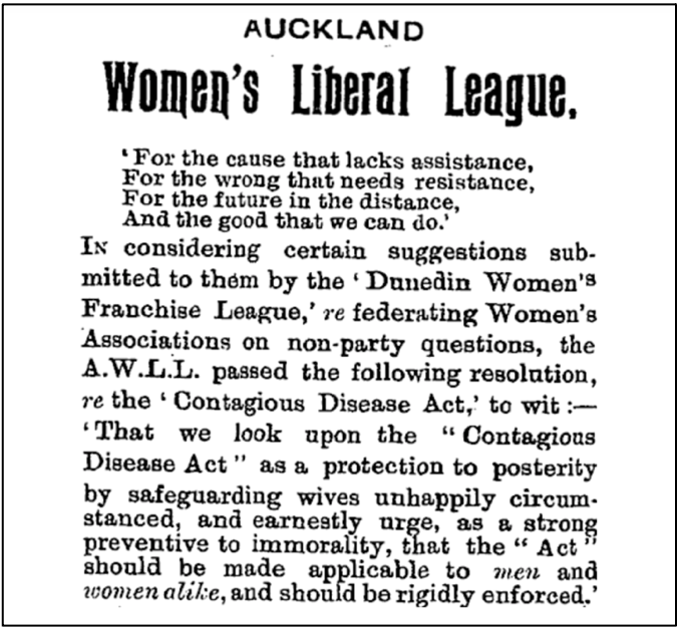

Whilst the consensus among the AWPL and the AWCTU was that the C.D. Act was an offensive piece of legislation, the Auckland Women’s Liberal League held a different view. Rather than advocating for its repeal, the Liberal League believed the C.D. Act protected women from venereal disease and asked for the Act to be re-implemented and enforced more vigorously. In a resolution published across all local newspapers, the Liberal League stated that it believed the C.D. Act to be a “protection to posterity by safeguarding wives unhappily circumstanced” and that it should be “brought into operation, and fearlessly and rigidly enforced”. Unlike the AWPL and the AWCTU, the Liberal League stressed that everywhere the C.D. Act had been enforced had seen lower rates of venereal disease. Arguing against the social purity argument put forward by the other groups, the Liberal League claimed that moral persuasion against sexual immorality had “never yet lowered, nor is all likely to lower, the statistical record of those who are poisoning the life blood of the nation”. The Liberal League argued that leaving venereal disease “untrammelled by legal restrictions” would never create a “physically sound and morally untainted” society.

Despite the contrasting opinions of the three groups, the Liberal League agreed with the AWPL and AWCTU over the inequality present in the C.D. Act. The Liberal League made it clear that it was “emphatically opposed to the enforcement of the Contagious Diseases Act on women only”. Its support of the C.D. Act was therefore on the condition that the original C.D. Act be altered. The Liberal League resolved that it would only support the C.D. Act if the government updated it to apply equally to men and women. Additionally, the Liberal League stressed that the medical examinations of women would have to be done by female medical staff alone. Once applied to both sexes, the C.D. Act would act as a “preventative to juvenile and adult immorality” and reflect “society’s protest against prostitution”. Despite holding a position that conflicted with other feminist groups in Auckland, the Liberal League saw itself as “performing one of the highest duties imposed on the women of New Zealand by the enfranchisement of the sex” through its support of the C.D. Act.

Auckland Women’s Liberal League’s resolution in favour of the C.D. Act. Source: “Auckland Women’s Liberal League.” Observer, 29 June, 1895.

Success…for some.

After years of protest from feminist groups and politicians across the country, the C.D. Act was finally repealed in 1910. The removal of the C.D. Act from the statue books was a source of great satisfaction for the AWCTU and the AWPL, who had finally seen the success of a campaign lasting over two decades. Whilst this was a victory for some feminists, for others, like the members of the Liberal League, the repeal of the C.D. Act was not the outcome they had hoped for. The contrasting positions of the Liberal League, who supported the Act, and those of the AWCTU and AWPL, who rejected it, reflect an interesting dynamic in feminist thought at that time. The popularity of the AWCTU and the AWPL’s positions, and the level of criticism given to the Liberal League for their statements, begs the question: was there a ‘right way’ to be a feminist in late nineteenth-century New Zealand? And, if so, what can this tell us about feminism in the twenty-first century?