Part Three

The fluidity of Ngāti Te Ata rohe

by Tommy de Silva*

It is a common misconception that historic Māori lived rigid and stagnant existences. One part of this misconception is that tangata māori groups occupied small scale, stagnant and exclusive rohe (territory). Although this narrative affirms colonial rhetoric, it could not be further from the truth to Māori. In this article, I will challenge this misleading and limited idea about tangata māori rohe, an idea that the Crown largely proliferated. Through exploring the historic Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua rohe, I will show that historic tangata whenua occupied large scale, fluid rohe with overlapping claims to certain resources or areas by different rōpū.

The clash of two opposing views of land ‘ownership’

In these motu, after the coming of the Pākehā, there was a great clash between indigenous and foreign perceptions of land ‘ownership’. These two opposing views were the tikanga and Western understandings surrounding land.

An 1870 Auckland (Parnell Rise) example of the epitome of 19th Century Western land use, a factory tasked with capitalistic production. Source: Frith, Samuel G. PH-NEG-A1521 ‘Union Sash and Door Factory, Parnell Rise’. 1870. Gelatin dry plate negative supported by glass. Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira: Collections Online Photography, Auckland.

Under tikanga, historic tangata whenua had no concept of land ownership in the Western sense. Some key differences were that individual ownership of the whenua was inconceivable, and that land was typically not exclusively occupied. Instead, whenua was held in common. In most situations, a system of cooperative agriculture led to the sharing and redistribution of resources. On rare occasions, exclusive use of the whenua or its resources was recognised. But claims to certain areas or resources were malleable due to constant negotiations and territory disputes. As such, whenua and resources often had several overlapping yet totally legitimate claims by different rōpū. According to Muru-Lanning, “one tribe may have had the rights to harvest birds in an area at a particular time of the year while another tribe may have had the fishing rights for the area and a third tribe may have had the rights to grow crops”. Claims to whenua and resources were usually connected to inherited mana and a group’s history of use and occupation in the area (ahi ka). The tangata māori relationship with the whenua was one of responsible resource management to fulfil one’s obligations to their collective in their present and future alike while not undermining the area’s mauri.

The Western understanding of land ownership was starkly different with ideas of land ownership in these motu originating from British common law. Under common law, ownership of property is usually vested privately in the individual. It is then said individual’s duty as a landowner to ‘develop’ their land to add to its value. This land development typically meant establishing some form of a capitalistic enterprise, like a farm or a factory. Philosophically this land development was an exercise in conquering and taming nature. Furthermore, embedded within Western religion and property philosophy was permission for Pākehā to confiscate Indigenous People’s land and resources if it was not being developed in a Western manner. In this sense, land development in colonies was not as much an exercise in taming nature as it was a practice of conquering Indigenous Peoples.

Geographically contextualising historic Tāmaki

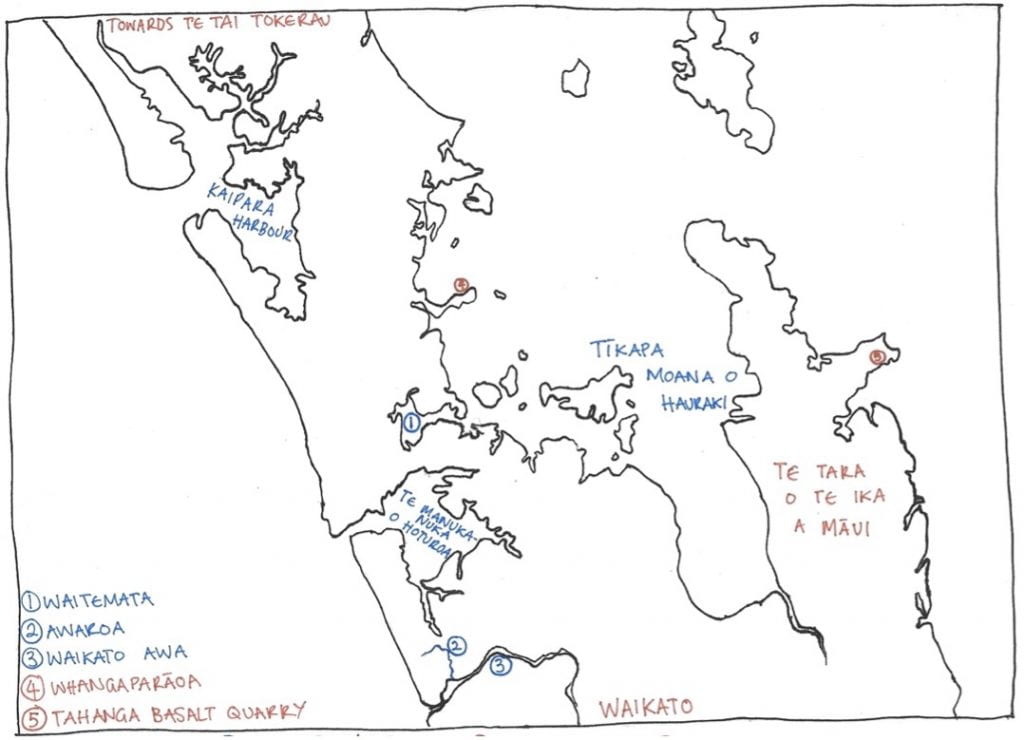

Along with being positioned on a fertile volcanic field and neighbouring moana to both the west and east, historic Tāmaki sat at the meeting point of several ‘highways’ of its day. These ‘highways’ were water-based transportation systems for waka that moved people, trade goods, and information across the region. At no less than eight points in Tāmaki, there were portages, places where waka were landed and transported over the land to another nearby awa or moana to continue one’s journey. Tāmaki’s geographic location provided its tangata māori with easy access north, south and east.

Rōpū from Tāmaki could easily access the Kaipara Harbour on their path northward via Whangaparāoa. According to archaeological evidence, Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) was the most populous historic region as it was the best place for growing available crops. With so much of the tangata māori population living in Te Tai Tokerau it was a significant historic region, making easy access from Tāmaki geopolitically and socially vital. To the east, Tīkapa Moana o Hauraki (the Hauraki Gulf) enabled access to the Hauraki and te Tara o te ika a Māui (Coromandel) areas. Eastward access was important for several reasons. For example, te Tara o te ika a Māui was a large source of stone, like basalt, for tools. Lastly, Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa (the Manukau Harbour) provided access southward via the Waikato Awa. Southward access was especially important for Ngāti Te Ata because the Te Pae o Kaiwaka portage between Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa and the Waikato Awa was near the Ngāti Te Ata heartland, and as such was named after it. Through this southward access, Ngāti Te Ata could interact with their Waikato whanaunga (relatives).

A map to visualise the geographical context of historic Tāmaki as discussed in this section. Source: Commissioned Drawing Four. 2022. Drawing on paper by Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Auckland.

Tāmaki sitting at the ara rīpeka (crossroads) of several important transportation routes meant that the region did not exist in a vacuum. Instead, it was only one part of the broader tangata whenua world. Because of its centrality to several transport networks over time Tāmaki gained a new title – Tāmaki Herenga Waka – meaning Tāmaki the gathering place of many waka. It is important to geographically understand historic Tāmaki as Tāmaki Herenga Waka, an important ara rīpeka in the wider historic tangata whenua world. Through being one part of a larger sphere of interaction, the region of Tāmaki was itself highly fluid, much like the rohe of its inhabitants.

The fluid rohe of Ngāti Te Ata

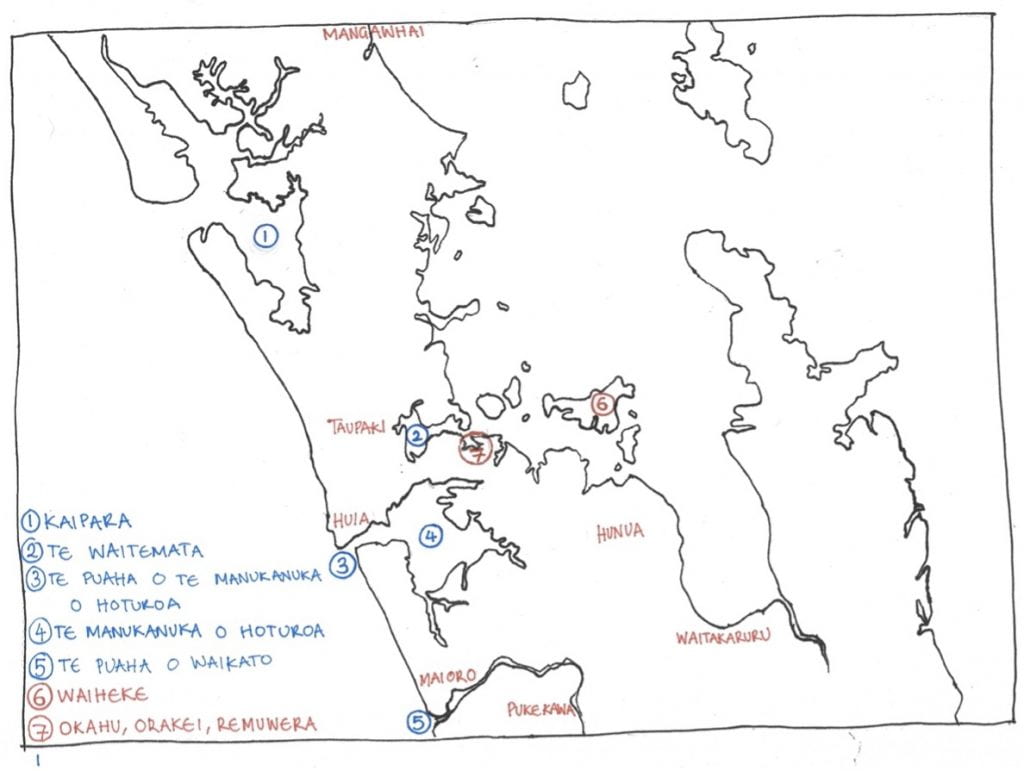

Fortunately, Roimata Minhinnick from Ngāti Te Ata has poetically outlined the traditional Ngāti Te Ata rohe. He said:

Traditionally… the rohe of Ngāti Te Ata Waiohua embraced Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland Region) beginning at Maungawhau, the foundation of Te Wai o Hua, consolidating Nga Iwi and Nga Oho under the waters of Huakaiwaka, overlooking Te Waitemata. The rising sun awakens Ngati Te Ata Waiohua from the depths of the Manuka forming a genealogical alignment from Maungawhau to Matukutureia, the foundations and mauri (life force) of Ngati Te Ata Waiohua. The stand of Te Rangihahautu ascends Te Manurewa o Tamapahore and accompanied by Te Horeta heading directly toward Whenua Kite, to the Southeast. It then transcends westward and extends the breadth of the Wairoa ranges south to Pukekowhai before reaching the banks of the Waikato River and being alerted to its mauri. From Pukekawa it turns to salute Te Paki o Matariki before embracing ngā motu that lead toward Te Puaha o Waikato. From Maioro the site of Ngā Wai Hohonu o Rehua opens the path along the ancient lands of Paorae to Te Puaha o Manukau. The stand at Pukehorokatoa is followed by a tribute to Uenuku, Kaiwhare and Puketapu before crossing Te Whare o Te Atua to gather Te Rau o Te Huia. The stakes placed at Taupaki reaffirm the takiwa abounds the southern shores of Kaipara. From Hikurangi, Te Totara Tapu o Huatau places a moko over the land. The deep tattoo of Te Kahupokere sustains Te Kainga Ahi through Okahu, Orakei, and Remuera in full abode at the height of its prosperity. At Mauinaina the bonds of Te Tawha endure and cross to Waiheke where the treasured kowhatu remains steadfast…

This rohe explanation can be furthered by adding that Ngāti Te Ata territory extended:

From the mouth of the Waikato River to the mouth of the Kaipara in the West. From the mouth of the Kaipara across to Mangawhai in the North. From Mangawhai to Waitakaruru-Piako in the East. From Waitakaruru-Piako to Pukekawa returning to the mouth of the Waikato in the South. The Tasman Sea, Southern shores of the Kaipara Harbour, Waitemata and Manukau Harbours including the Waikato River are the water ways. Puketapu, Maungawhau, Maungakiekie, Maungarei, Matukututureia and the Hunua Ranges are in between.

A map visualising some of the places discussed in this rohe section, highlighting the expansive and as such fluid nature of Ngāti Te Ata rohe. Source: Commissioned Drawing Five. 2022. Drawing on paper by Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Auckland.

Contextualising the fluid rohe of Ngāti Te Ata

As I have mentioned at the beginning of this article, it is popularly believed that historic Māori occupied small scale, stagnant and exclusive rohe. In reality, the traditional rohe of Ngāti Te Ata was far from small as evident in both the description by Roimata Minhinnick and in the map above. In modern terms, historic Ngāti Te Ata rohe extended from the northern Waikato, through the whole mainland-bound Auckland region to the border off Northland. Large parts of this expansive rohe were not exclusively occupied. Across the traditional Ngāti Te Ata rohe, there were overlapping yet recognised claims to some of the same areas by different rōpū. Different rōpū had claims to different, or sometimes the same, resources or rights within overlapping areas. The lower (Northern) Waikato Awa area was a good example of how these overlapping claims worked.

View of Te Puaha o Waikato from the Maioro area. Source: Townsend, J.E. Footprints 04819 ‘South Waikato Head, Maioro, ca 1950’. 1950. Film photograph print. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Kura, Auckland.

The lower Waikato Awa around Te Puaha o Waikato, the northernmost section of the river that eventually flows into the sea near modern Port Waikato, provides an example of overlapping claims. Ngāti Te Ata joined Ngāti Tahinga, Ngāti Karewa, Ngāti Tipa, Ngāti Kaiaua, Ngāti Amaru and Ngāti Pou in sharing the fishing rights for the lower Waikato Awa. Here these various, yet interrelated, groups all collected eel, freshwater crayfish, whitebait, mullet, flounder, shellfish, waterfood and wild vegetables. The lack of historic occupational exclusivity around Te Puaha o Waikato highlights the fluid nature of tangata māori rohe. Areas like the lower Waikato Awa were not exclusively occupied, exemplifying the fluidity of tangata māori rohe in that access was open to more than one group. The broader boundaries of rohe were also fluid as constant negotiation and disputes over territory meant that rohe and rights to certain places were malleable over time.

There were examples of where tangata māori rohe was exclusively occupied. In between Te Puaha o Waikato and Waiuku is Maioro. As acknowledged by Roimata Minhinnick, Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua held the exclusive mana in this area, a fact supported by the Māori Appellate Court. The Tainui Trust Board, the representative for the diverse Tainui iwi and hapū, affirmed that Ngāti Te Ata has been the time-immemorial kaitiaki of Maioro. If other iwi and hapū came to the area without first securing permission they could expect violent repercussions. With permission external rōpū could for example access Maioro en route to fishing expeditions on te Manukanuka o Hoturoa.

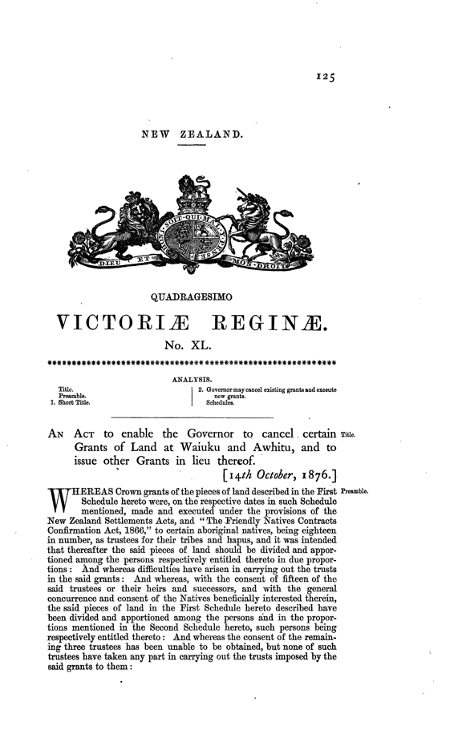

The origin of the idea of small-scale, stagnant and exclusive rohe

The Crown founded the untrue narrative about tangata māori rohe explored in this article. In its quest to take the whenua from tangata whenua, the Crown sought to break tangata māori land up into smaller, more ‘digestible’, chunks. Ultimately, historic Māori common land ‘titles’ were abolished by the Crown in favour of individualised titles in the latter third of the nineteenth century. The individualisation of land titles made land purchases a simpler and faster process for the Crown, as fewer people were involved and as such fewer people could claim the land or air grievances. Traditional decision-making processes, based on group consensus, were ‘sidestepped’ through individualised titles. By redefining tangata māori territory and neatly splitting it into smaller sections, the Crown and its wealthy settlers could buy up indigenous land more easily and cheaply. Afterwards, landowners then on-sold the whenua at a profit to a Pākehā ripe with the dream of capitalistic development.

Opening page of the Waiuku Native Grants Act 1876 that eradicated Ngāti Te Ata common land titles. Source: New Zealand Legal Information Institute. Waiuku Native Grants Act 1876 (40 Victoriae 1876 No 40). 2015. PDF copy of legislation. University of Canterbury/University of Otago: New Zealand Acts 1841-2007 As Enacted Collection, Christchurch/Dunedin.

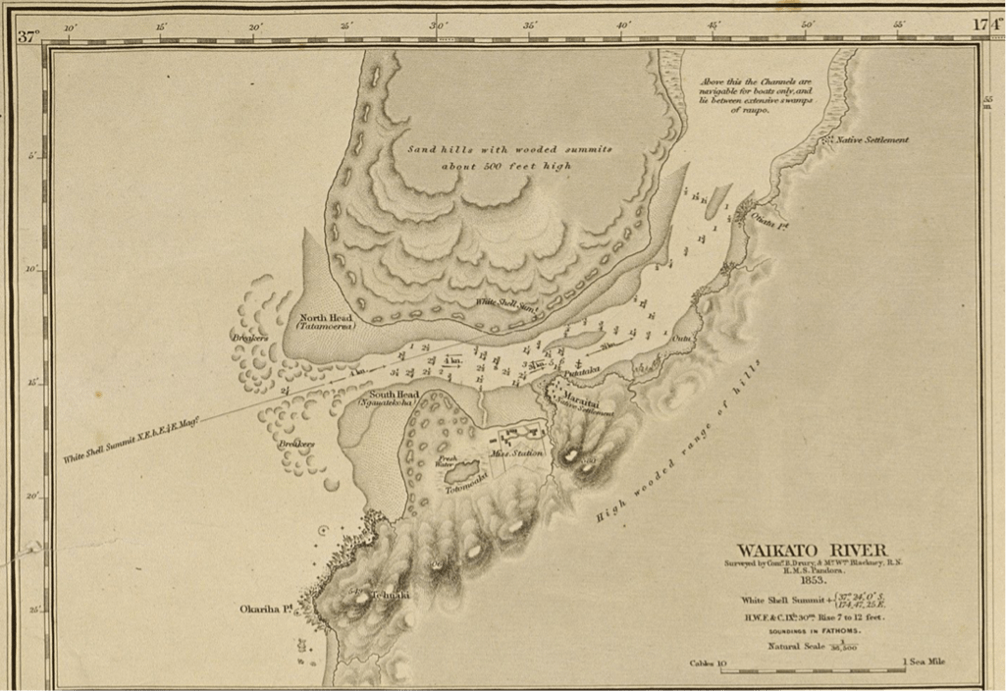

By analysing the rhetoric of government officials in the nineteenth century, it can be understood that the Crown was promoting the idea of stagnant and exclusive rohe. In 1869, Judge Fenton of the Native Land Court falsely claimed that, “An understanding was clearly arrived at by previous generations that each of the tribes around Manukau… should possess and occupy certain fixed, and more or less well-defined, portions of the country”. From the Western viewpoint, the Ngāti Te Ata rohe explanation given above does not represent a fixed or well-defined territory. Nor would the rohe of other tangata māori. Rohe was typically not fixed. Crown officials were also unable to translate rohe into well-defined, and therefore by default, exclusive territories due to the many overlapping claims to areas and resources. How would a Western-style map, with its fixed boundary lines, show the shared fishing rights in the lower Waikato Awa? Obviously, the tikanga and British common law understandings of land use were incomprehensible and incompatible to one another.

A Western-style map drawn in 1853 showing part of the lower Waikato Awa. Source: Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty. Map 873 ‘Manukau Harbour to Cape Egmont Map: Waikato River Map’. 1857. Nautical chart. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Kura, Auckland.

Conclusion

Historic Māori prospered freely across large scale, fluid and cooperatively occupied rohe. Even Tāmaki Herenga Waka itself was a fluid entity, as it sat at an important ara rīpeka (crossroads) within the wider historic tangata whenua world. The landscape of these motu was a series of overlapping yet recognised claims to areas and resources that were malleable. Through this tikanga system of land use, tangata whenua were the kaitiaki of te taiao (the natural environment), upholding its mauri so that future generations could be sustained from her. However, with the imposition of Crown common law, a Western legal relationship between the land and her people was enforced. The Crown used this legal relationship to acquire tangata whenua land and resources in order to promote capitalistic colonialism. En route to action this, the Crown promoted the idea that tangata māori groups should have the exclusive rights of occupation within small, immobile areas.

In the next article in this series, I will explore the flexible attitudes and viewpoints within Ngāti Te Ata around the time of the Waikato War. This article will demonstrate the diverse opinions within the historic Māori society, even within the same rōpū like Ngāti Te Ata, to challenge the common misconception that tangata māori all thought and acted as one.

Kupu Appendix

- Kaitiaki | A kaitiaki is an individual or group who act as the ‘guardian’ of a certain natural environment through enacting kaitiakitanga

- Mauri | The life force present in te ao Māori that connects the physical and spiritual spheres in order to give the capacity for life