Part Four

Diversity of thought and action within historic Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua

Part Three

The fluidity of Ngāti Te Ata rohe

by Tommy de Silva*

In popular culture, historic tangata whenua are thought of as one unified people whose thoughts and actions were identical or at least very similar across the motu. This notion of unity is not based on historical evidence but was instead a narrative promoted by colonial institutions. The tangata māori world was made up of independent, yet interrelated, rōpū who were diverse in thought and action relative to one another.

The diverse ideas and practices of historic tangata whenua was not only prevalent between groups but also within them. This article will explore the diverse ideas and actions inside Ngāti Te Ata regarding the Waikato War. New Zealand’s ‘Great War’ (Waikato) polarised Ngāti Te Ata, splitting the rōpū between its two sides. Within the contemporaneous rōpū, some outrightly supported, and fought for, te Kīngitanga and some supported, and aided, the Crown. These opposing perspectives within historic Ngāti Te Ata help to demonstrate the varied thought and action present in historic tangata whenua society.

The unique geopolitical position of Ngāti Te Ata

As discussed in my second article, Ngāti Te Ata became an important connection on the Waikato-Auckland trade route. From the blossoming of the Waikato-Auckland trade route, Ngāti Te Ata formed an early relationship with the Crown. Ngāti Te Ata also had early relationships with other Pākehā, namely missionaries, traders, and ordinary settlers. Early land ‘sales’a were rampant in Ngāti Te Ata rohe, both before and after the Treaty, increasing Ngāti Te Ata-Pākehā interactions. Before 1840, land ‘sales’ were private affairs between Ngāti Te Ata and individuals, like settler Alexander Dalziel who ‘purchased’ 1,800 acres in 1839. After 1840, the Crown on and off used its right of pre-emption for ‘purchasing’b land. Also, from December 1851 through to April 1854, the foundations for the Pākehā Waiuku Village within Ngāti Te Ata rohe were laid out.

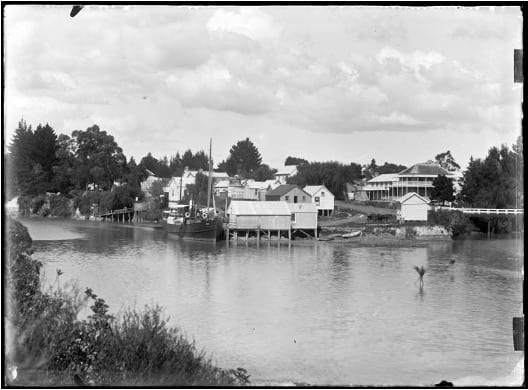

Waiuku village near the end of the 19th century. At this site from the early 1850s Ngāti Te Ata interacted with Pākehā. Source: Dawes, Charles P. 1572-1519 ‘View of Waiuku from across the river, 1895’. 1895. Glass plate negative. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Kura, Auckland.

This series of early interactions led to a positive relationship between Pākehā and Ngāti Te Ata. Ahipene Kaihau, principal rangatira of Ngāti Te Ata around the time of the Waikato War, deeply cared for and protected local Pākehā. Understandably, it would be difficult for Ahipene to not care about people he had known for so long, some of them for over a decade. We can understand the affinity Ahipene had for the local Pākehā through his letters.

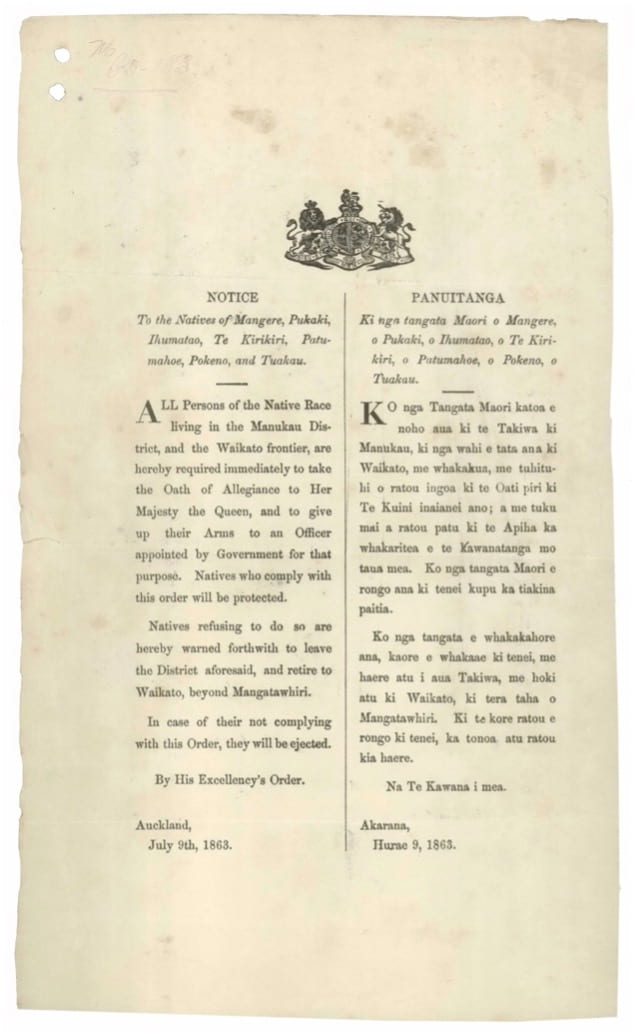

On 4 July 1863, eight days before the Crown instigated war by invading the Waikato, Kaihau wrote to Kawana (Governor) George Grey. Written during a point of obvious military mobilisation, Ahipene asked the Crown for “protection of my Pakehas, for I do not approve of letting my Pakehas die.” In the same letter, Ahipene committed forty Ngāti Te Ata toa (warriors) to protect the Waiuku settlers from harm during the forthcoming conflict. In between Ahipene’s letter and the invasion on the 12th, Kawana Grey issued a proclamation requiring Manukau and some lower Waikato tangata māori to either take an oath of allegiance to the Crown and thereafter surrender their arms, or vacate the area and move southward beyond the Mangatawhiri stream. Yet, Ngāti Te Ata was effectively exempt from Grey’s proclamation. Instead of expecting Ngāti Te Ata to adhere to the proclamation, the Crown officially listed the rōpū as friendly, meaning they were not considered an enemy during the Waikato War.

The Crown’s proclamation prior to the Waikato War. Notice that the proclamation does not apply to Ngāti Te Ata centres like Waiuku. Source: Archives New Zealand. 2015. MA1 Box 835/ 1863/186 ‘Proclamation requiring Māori to take an Oath of Allegiance, 9 July 1863’. 2015. Digital scan. Archives New Zealand: Flickr, Wellington.

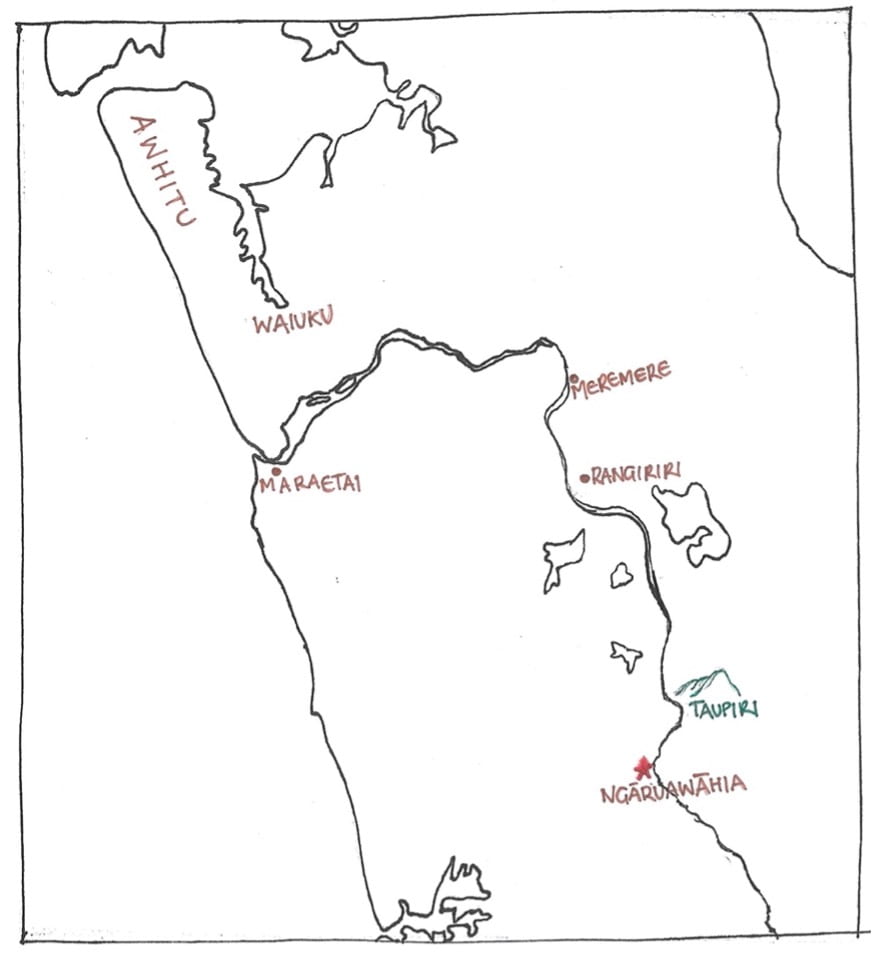

Alongside having a positive relationship with the Crown, Ngāti Te Ata also had a positive relationship with te Kīngitanga around the time of the Waikato War. The kāhui ariki, the senior lineage family of te Kīngitanga, are of Ngāti Mahuta. Ngāti Te Ata and Ngāti Mahuta are connected through whakapapa. As such, Ngāti Te Ata and Ngāti Mahuta are whanaunga (relatives). Both rōpū exercised mana in areas nearby one another, as Ngāti Mahuta rohe occupied parts of the lower Waikato.

When a group of warriors from Waikato under Te Wherowhero lived in Tāmaki to protect the locals from northern taua (war parties), one of their primary residences was on the northern Awhitu peninsula. On the Awhitu peninsula their direct ‘neighbours’ were Ngāti Te Ata. Through their multifaceted closeness, Ngāti Mahuta and Ngāti Te Ata interacted with one another across time. The mid-nineteenth century trade from Waikato to Auckland necessitated increased interaction between Ngāti Te Ata and Waikato rōpū, like Ngāti Mahuta, at important trade centres such as Waiuku and Onehunga. But Ngāti Mahuta is only one of the rōpū that made up te Kīngitanga.

Map showing the geographic closeness of Ngāti Te Ata and Ngāti Mahuta. Taupiri is the sacred ancestral maunga of several Waikato rōpū including Ngāti Mahuta. Below Taupiri is Ngāruawāhia, which would become the capital of Te Kīngitanga before the Waikato War. Further north are Meremere and Rangiriri, two more Waikato centres where Ngāti Mahuta had a large presence, the latter being the site of a famous battle. Maraetai (modern Port Waikato) was a significant site for historic Māori-Pākehā contact within the lower Waikato, and a place where Ngāti Te Ata and Ngāti Mahuta would have sometimes interacted. Source: Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Commissioned Drawing Six. 2022. Drawing on paper. Auckland.

Other adherents included Waikato based rōpū such as Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Haua, alongside groups from further afield. For example, long-time Ngāti Te Ata Tāmaki neighbour Ngāti Tamaoho was one of those Kīngitanga supporting rōpū that was expelled from Auckland by Grey’s proclamation. Yet, there is a point of deep connection between many of the Kīngitanga adherents and Ngāti Te Ata. Ngāti Te Ata has a shared whakapapa with many of the Kīngitanga hapū and iwi from the Tainui waka. This shared whakapapa indestructibly connected Ngāti Te Ata with te Kīngitanga.

Contextualising the unique geopolitical position of Ngāti Te Ata

Through its relationships with both the Crown and te Kīngitanga before the Waikato War, Ngāti Te Ata occupied a multifaceted position during the conflict. As will be expressed later in this article, members of Ngāti Te Ata did not collectively subscribe to a unanimous perspective regarding the Waikato War. Instead, individuals or small groups within Ngāti Te Ata seemed to make their own decision as to which side they would support during the war. It is safe to assume that the personal relationships that individual Ngāti Te Ata members had with Pākehā and te Kīngitanga supporters played a role in which side they took.

Theorising diversity of thought and action within one rōpū

In her text Tupuna Awa, Marama Muru-Lanning, effectively theorises the diversity of thought and action within Māori rōpū. Although Marama’s text focuses on the modern socio-political context of the Waikato Awa, her thoughtful exploration of this topic can be validly applied to explain the diversity within historic tangata whenua groups. On Māori, Marama states, “What is clear is that identity is fluid and cannot simply be tied to place or occupancy, political allegiance or genealogy.”. Paraphrasing Joseph’s 2005 work, Marama acknowledged that Māori from one area “are not homogenous with an easily definable shared set of interests”. Internal differences are inherent within groups, argues Marama, as people have different interests and connections to places, allowing for contradictory opinions to exist within rōpū. Contradictory opinions are formed because Māori from the same group do not necessarily share the exact same whakapapa and history of interactions with external rōpū. Marama’s ideas can be applied to Ngāti Te Ata, a group that around the Waikato War internally harboured opposing views.

The Ngāti Te Ata-Crown relationship during the Waikato War

In July of 1861, Donald McLean, effectively the Crown’s spymaster, was informed by Charles Marshall that Waiuku tangata māori, undoubtedly including some Ngāti Te Ata members, had professed their loyalty to the Crown. Before the Waikato War, our Rangatira Ahipene Kaihau had become a ‘native assessor’ for the Crown. Native assessors worked within the Native Land Court system. Through his position within the Native Land Court, it appears that Ahipene formed positive personal relationships with Crown officials. Importantly regarding the Waikato War, Ahipene had personal relationships with George Grey and Donald McLean. It seems that Ahipene had a particularly strong relationship with Grey, whom he acknowledged as his friend. Ahipene even personally invited Grey to Waiuku on many occasions, including just before the Waikato War. The personal relationship between Ahipene and Grey certainly would have contributed to Ngāti Te Ata being officially listed as ‘friendly’ during the Waikato War.

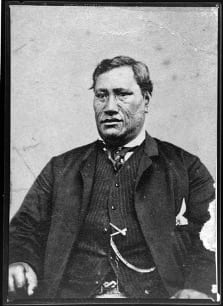

Ahipene Kaihau in 1864. Source: Richardson, James D. 4-1366 ‘Aihipene (Ahipene) Kaihau, chief of Ngati Te Ata… 1864’. 1864. Film negative. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

On 20 July 1863, eight days following the outbreak of war, Waiuku based Ngāti Te Ata again asserted their loyalty to the Crown to a Daily Southern Cross correspondent. The Ngāti Te Ata members encountered by the correspondent were still in possession of their arms, indicating their friendly status with the Crown. Similarly, some Ngāti Te Ata came to work with the Crown during the Waikato War. When Crown supplies briefly ran through the Awaroa portage for the month of August in 1863, Ngāti Te Ata planned to aid in transporting the supplies. Working with the Crown again in November of 1863, a group of twenty Ngāti Te Ata accompanied by Mr Puckey from the ‘Native Department’ destroyed a fleet of waka. These examples underscore the relationship that some members of Ngāti Te Ata had with the Crown during the Waikato War – a relationship of cooperation and support. However, at the same time other members of Ngāti Te Ata clearly supported te Kīngitanga.

The Ngāti Te Ata-Kīngitanga relationship around the Waikato War

Prior to the Waikato War, it was already clear that some Ngāti Te Ata were prepared to fight the Crown in opposition to land and sovereignty theft. This much is clear when reading Henry Halse’s letters to spymaster Donald McLean. In two letters dated March 1861, Halse outlined that some members of Ngāti Te Ata strongly wished to fight in the Taranaki War against the Crown . However, also according to Halse, Te Katipa, then paramount rangatira, would not permit any Ngāti Te Ata members to partake in the conflict. Halse warned McLean that if any Ngāti Te Ata fought against the Crown in Taranaki, the whole rōpū would be dragged into the war. Such an occurrence would have likely cost Ngāti Te Ata its friendly status with the Crown during the Waikato War.

Donald McLean in the 1870s. During the 1870s McLean held the coveted ‘Native Minister’ office in Wellington. As ‘Native Minister’ McLean exerted powerful influence on Crown-Māori relations during a period when Māori land titles were being individualised. Source: Carnell, Samuel. 51/122-1580 ‘Sir Donald McLean’. Unknown date (1870-1877). Black and white photograph glued to card. MTG Hawke’s Bay: Collection of Hawke’s Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi, Napier.

Even before the onset of the Waikato War, it was obvious that Ngāti Te Ata and te Kīngitanga had a friendly relationship. As was mentioned in my second article, representatives of Ngāti Te Ata supported several important Kīngitanga hui. During the Waikato War, there were more signs of Ngāti Te Ata support for te Kīngitanga. On 25 August 1863 two Ngāti Te Ata Waiuku ‘policemen’, Tipene Te Tahuna and Henare Kaihau, were dismissed from their positions for supporting te Kīngitanga. In that same month, at least forty-seven Ngāti Te Ata had left Waiuku and gone to the Waikato to support their whanaunga. Indisputably, some of those forty-seven Ngāti Te Ata fought alongside te Kīngitanga toa against the Crown.

After the battles of Rangiriri and Orakau, and the war crime that was the murderous sacking of Rangiaowhia, some Māori prisoners were held on the prison-ship Marion. On the second page of the Marion prisoner list, the first noticeably Ngāti Te Ata name to me appears, Maihi Katipa. Maihi was the son of former rangatira Te Katipa, and he was captured at Rangiriri. Also taken prisoner at Rangiriri, was the aforementioned Tipene Te Tahuna whose name sits three names below a pair of Katipa’s on the Marion’s prisoner list. Overall, at least thirty-five Ngāti Te Ata prisoners were on board the Marion. However, those thirty-five members of Ngāti Te Ata held on-board the Marion would not have represented the full number of the iwi who fought for te Kīngitanga during the Waikato War. But those thirty-five were significant to the wider rōpū, as ultimately, Ahipene Kaihau would lose his position as a Crown assessor by appealing for their release.

Conclusion

It seems that in the years following the Waikato War, the Ngāti Te Ata-Crown relationship deteriorated, and the Ngāti Te Ata-Kīngitanga relationship blossomed. According to Henry Turton, by September 1865, it was clear that Ngāti Te Ata had come to distrust the Crown. As will be explored in the next article, Ngāti Te Ata felt the full force of the Crown’s wrath after the Waikato War, leading to said distrust. Yet, the Ngāti Te Ata-Kīngitanga relationship bloomed further.

By 1872, Ahipene Kaihau had become the brother-in-law and trusted advisor of Tawhiao, the second Māori king. At this point, Ahipene moved from his turangawaewae to the king’s ‘court’ in Te Rohe Potae (the King Country). One important role Ahipene had was acting as an emissary between Tawhiao and the highest-ranking Crown officials. On 29 June 1872, Ahipene met with Governor George Bowen and Donald McLean, who was by then the Minister of Native Affairs, on behalf of Tawhiao. Ahipene’s son, Henare Kaihau (I am unsure whether or not he is the aforementioned Henare Kaihau, who was expelled as a policeman), would become a principal advisor to the third Māori king Mahuta while also serving as a member of parliament (MP). Through his position as an MP, Henare was an emissary between the leaders of Te Kīngitanga and the highest Crown offices, much like his father. Undoubtedly, the Kaihau’s previous relationships with the Crown and their understanding of te ao Pākehā through a long history of interaction made them invaluable advisors to the Kahui ariki.

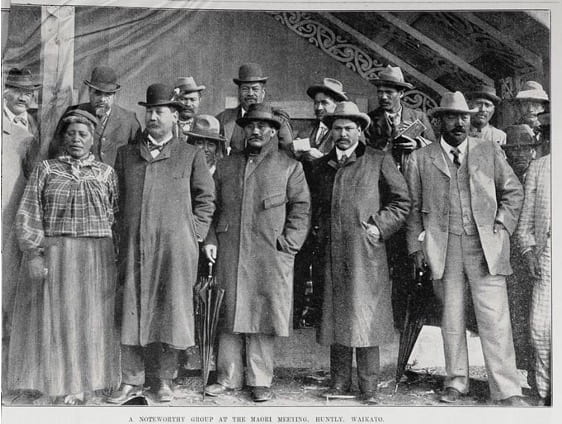

Henare Kaihau (front row, far right) with significant male Māori politicians and leaders of the day. From left to right in the front row: James Carroll (Native Minister), King Mahuta (Te Kīngitanga), Doctor Maui Pomare (future Minister of Health). Source: Auckland Weekly News. AWNS-19020529-9-1 ‘A noteworthy group at the Maori meeting, Huntly, Waikato’. 1902. Digital image scan. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

Around the time of the Waikato War, Ngāti Te Ata had internal divisions of opinion as to which side of the conflict to support. From these multifaceted opinions within Ngāti Te Ata came diverse actions. Some members aided the Crown and others fought alongside te Kīngitanga. These fluid ideas and practices within historic Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua were only one of many examples of the diverse thought and action within tangata māori society. On the contrary, the Crown’s rhetoric as to whom they viewed as their enemy following the Waikato War was largely inflexible, as will be explained in the next and final article in this series.

Kupu Appendix

- Rangiaowhia war crime | Rangiaowhia was a flourishing Waikato settlement and the Crown jewel of tangata māori agriculture. It had been agreed upon by te Kīngitanga and the Crown as a safe-zone for wahine, tamariki and kaumātua during the Waikato War. Regardless of its commitments, in February 1864, the Crown sacked the settlement killing and taking prisoner non-combatant women, children and elderly. Ngāti Apakura were the main group at Rangiaowhia, and following the war some of the displaced rōpū found refuge in Awhitu near Ngāti Te Ata, in a reverse of the protection afforded to Ngāti Te Ata by Waikato rōpū during the Musket Wars.

- Right of Pre-emption | As agreed upon under the Treaty of Waitangi, this notion gave the Crown first right of refusal to ‘buy’ any whenua in the motu, ahead of private individuals or groups.

- ‘Sales’, ‘purchased’ | These terms are emphasised within this series because to tangata māori no such purchases or sales ever occurred. Purchasing and selling are tauiwi (outsider) ideas that promote exclusive and restrictive ownership, and there were no equivalent concepts for them within te ao Māori. Tangata māori would never have conceived that by ‘selling’ their whenua to tauiwi that the land would then become inaccessible to them. Traditionally land was shared among kinship and allied groups. Tangata māori who ‘sold’ land to Pākehā believed that their, and their descendants, mana and kaitiakitanga over the whenua would not be extinguished through land ‘sales’.