Part Three

Cultural Conflicts and Evolutions in Late 1960s-1980s Auckland Theatre

by Anna McCardle*

Recently, the Australian Federal Government indicated that it planned to bring in laws that would oblige streaming companies like Disney and Netflix to “reinvest money in the local market.” Companies may be required, in addition, to create a set amount of streaming content within Australia. Aotearoa New Zealand screenwriters have expressed their hope to have similar regulations implemented here, aiding the growth of domestic film and television. Many of us love to see New Zealanders or Aucklanders writing and producing local content for the screen; telling stories shaped by and reflecting our cultures. Critics may point out, however, that Kiwis still inhale the transnationally produced content on Netflix or Disney+. We are significantly influenced by cultural influences from abroad.

In our recent history, there was a similar preoccupation with the cultural content of Auckland theatre. Auckland theatre companies like the Mercury were concerned with what kind of cultural influences they should allow their productions to be shaped by. Specifically, they were conflicted between prioritising English theatrical tradition, or staging an increasing number of locally written plays telling New Zealand stories. This is not unlike the contemporary conflict between favouring transnational or locally produced streaming and screen content. Moreover, there was a considerable lack of cultural diversity within Auckland theatre and this arguably helped to motivate the emergence of Auckland’s Pacific Theatre company.

This article explores the cultural conflicts and evolutions that unfolded in the late 1960s-1980s era of Auckland theatre, taking a microhistory approach focusing on Mercury Theatre and Pacific Theatre as case studies. Elizabeth McRae, who acted with Mercury Theatre from its first 1968 show, and Justine Simei-Barton, who founded Pacific Theatre in 1987, were both interviewed by Jean Hyland. Their first-hand experiences with these theatres provide valuable insights.

Mercury Theatre

Conflict over Staging New Zealand Plays

As Elizabeth McRae remembered, the emergence of professional theatre companies within New Zealand (like Mercury Theatre, founded in 1968) offered increased opportunities for plays to be staged here, and seemed to push New Zealand playwrights to “come in on the game.” In the 1970s, McRae observed a surge of New Zealanders writing plays that represented and told stories about our country. She found this change exciting and a “sea change” from theatre “being perceived as English and British” and all about “the latest English play.” The Auckland Theatre Trust’s 1967 promotional pamphlets, appealing for public donations to support the costs of setting up Mercury Theatre, outlined their plan to “offer a showcase for selected New Zealand plays of quality. This is a major need now that New Zealand playwrights are growing in number and stature.”

However, despite their advertised enthusiasm to showcase New Zealand plays, Mercury Theatre was, in reality, rather cautious and selective about staging them. McRae remembered the Mercury putting on New Zealand plays only “now and again… it was fairly rare because it was believed that the audiences wouldn’t come, you see.” Even on the rare occasions that a New Zealand play was staged, just a small number of them were judged as good enough to be staged in the main downstairs theatre. History professor and member of the Auckland Theatre Trust, Nicholas Tarling, recounted how the Mercury considered: “Could it risk putting on New Zealand plays in a large auditorium that was always a challenge to fill? Only a few justified the risk in financial terms.” New Zealand playwrights’ works were frequently slotted into the smaller upstairs theatre, or not selected at all. Even the New Zealand plays rarely judged as good enough to be performed downstairs were still viewed as “financial risks.”

Whilst there was a surge of New Zealand plays being written from the 1970s, the Mercury still questioned their quality and audience appeal. McRae recalled that “they would rather do a good English play” than a New Zealand production which had not been “proven” to be of high quality. The Mercury seemed wary about the newness and untested nature of plays that told New Zealand stories and looked culturally inward, and felt safer holding onto English ‘classics.’

Moreover, McRae perceived that audiences “stayed away in droves. Yes I remember we did stuff [New Zealand plays] in the little theatre at the Mercury and it was not a great [success].” Perhaps the Auckland public also shared the Mercury’s distrust in the quality of New Zealand plays. As Auckland’s first professional theatre company, the Mercury was a new and often financially precarious venture. It needed audiences to keep it afloat by paying for and attending shows, not ‘staying away in droves.’ Hence, the company kept its choice of plays fairly English and conservative, rather than run the financial risk of testing out many New Zealand plays.

Conflict between Hiring New Zealand or English Theatre Professionals

The Auckland Theatre Trust’s 1967 promotional pamphlets also promised that their initiative of founding Mercury Theatre would “provide employment for… New Zealand actors and actresses.” A similar 1967 news release outlined the Trust’s hope “that there will be many local actors and actresses interested in joining the company, and no appointments will be made until local auditions have been held.” Indeed, Auckland’s first professional theatre ensured it primarily hired Auckland and New Zealand actors. Tarling outlined that this was “welcome news among the theatre community.”

Advertisement calling Auckland actors to audition for the Mercury Theatre company, 1967, Mercury Theatre scrapbook, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection, https://digitalnz.org/records/32983639/mercury-theatre-scrapbook

Yet, in a similar manner to their caution at staging New Zealand plays, the Mercury seemed conflicted about prioritising New Zealand theatre talent. Tarling recalled how “some earlier statements at the foundation meetings were more in favour of recruiting from overseas.” Elizabeth McRae described how although the Mercury mainly had New Zealand actors, “they [the Mercury] thought because we had professional theatre we did have to get some English actors… [they] came over… [and were] full of stories about [how in England] they got their productions together in a week while they were busy playing something else at night.” Indeed, the recruited English actors were seen as coming from an impressive theatre background, able to elevate Mercury’s standard of shows.

Moreover, whilst their actors were primarily New Zealanders, the Mercury had a pattern of recruiting men from England to be the Director with ultimate control over the shows. When the company’s first director, Anthony Richardson, was hired in 1967, an Auckland Theatre Trust news release enthusiastically reported that he was a “Brilliant British Director… one of the top six Directors of the English Theatre… Dr. John Reid, Chairman of the Auckland Theatre Trust… [said] that the appointment of Anthony Richardson was the most exciting event in the history of the theatre in Auckland and perhaps in New Zealand.” Richardson’s English theatre credentials were viewed as prestigious and having a beneficial influence on Auckland theatre.

“Brilliant British Director” announcement. Auckland Theatre Trust, Director Appointed, News Release, September 4, 1967, 1-3, University of Auckland Special Collections, John Cowie Reid papers, Auckland Theatre Trust Records, MSS. Archives. 89/14. Series 4. File 17.

The Mercury’s director was appointed on the basis of having immense experience and talent, and as the Trust insisted, “irrespective of the nationality of the applicant.” However, when Ian Mullins succeeded Richardson, Tarling recalled how “appointing one Englishman had been acceptable, though it had not been without controversy; appointing a second was more questionable. Not only were there… New Zealanders who were worthy of the role, but there was also a feeling that what was now the leading New Zealand theatre ought to be led by a New Zealander.”

Mercury Theatre seemed to have had a conflicted approach towards New Zealand theatre. There was an incentive to make Auckland’s first professional theatre champion local and national culture. The Auckland Theatre Trust’s 1967 pamphlets proudly proclaimed their aims of founding “a New Zealand theatre” and “greatly enriching” the “cultural life” of Auckland. Yet there was an undercurrent of doubt in Auckland and New Zealand-centric theatre. In the questionnaire mailed to prospective Mercury directors in 1967, applicants were asked to “suggest a list of twelve plays to make up one year’s programme for a not-too-sophisticated city of half a million people.” It was implied that Auckland’s culture was less sophisticated or developed as that of cities of the United Kingdom and Europe. There was a cultural-cringe toward local content, whereas English theatre was viewed as an assured source of quality. This speaks to a broad insecurity and identity crisis that has arguably been ingrained both in Auckland and nationally over time, stemming from our history of colonisation: can Pākeha New Zealanders find their own cultural identity beyond being a satellite of the Motherland? Or is it safer to continue to follow English tradition? This also reflected the belief at the time that theatre patronage was predominantly white or pākeha and English-influenced, even with the large populations of Māori, Pacific peoples and Chinese in Auckland.

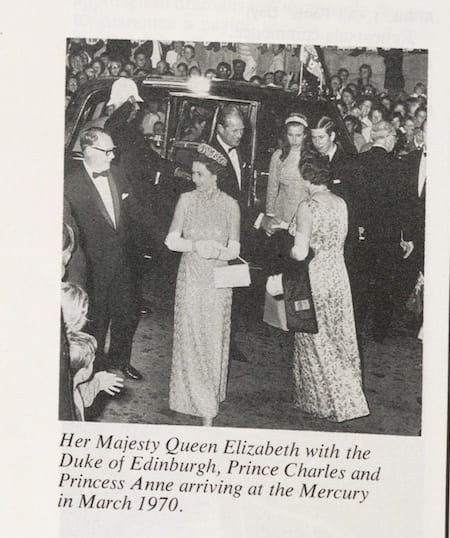

Queen Elizabeth II and members of the Royal Family at a Mercury performance of Earth and Sky on March 24, 1970. This likely would have been an immense source of pride for the Mercury. Mercury 5, 1968-1973, pamphlet, University of Auckland Special Collections, John Cowie Reid papers, Auckland Theatre Trust Records, MSS. Archives. 89/14. Series 4. File 17.

Pacific Theatre

Justine Simei-Barton on Late 1980s Auckland Theatre: There Was “Absolutely Nothing”

Justine Simei-Barton, a New Zealand-born Samoan director and actor, recalled seeing Mercury productions when she moved to Auckland in the late 1980s. She thought “they were good,” but gave an affirmative response when Hyland asked if she felt there was “nothing Polynesian about them.” There was a vast lack of Pasifika visibility and cultural diversity in Auckland theatre.

Simei-Barton grew up in a “close-knit” Pasifika community in Porirua and moved to Auckland to study Law at the University of Auckland. She experienced severe “culture shock” at the sheer lack of Pasifika theatre upon arriving: “I’d come from Porirua which is predominately Polynesian and… [you were] able to participate in the performing arts with your family and with your college and had that… support system and then to arrive in Auckland, one of the largest Polynesian cities in the world, and have absolutely nothing. I was quite horrified. I could not believe it.”

Indeed, Simei-Barton’s high hopes, based on Auckland having a larger Pasifika population than Porirua, were not met: “[I thought] that if I arrived up in Auckland …. ‘yeah there’s a larger population and there’s more Islanders, I’ll be OK.. there’ll be more support’ but I arrived to the exact opposite of what I was expecting.” This demonstrates how, although Auckland could have cultural diversity and large Pacific communities in its population, this was not always properly represented in spheres like the performing arts. What did Simei-Barton do when the reality of Auckland did not meet her expectations? She influenced change and cultural diversification in Auckland theatre.

“We’ll Have to Make a Start Then Won’t We?”: Founding the Pacific Theatre Company

Justine Simei-Barton remembered how when she was in the University of Auckland Library with her friends, she stumbled on a script for a Papua New Guinean musical, Feiva / Favour by John Kolia. She became determined to direct this musical with a Pasifika cast of actors, out of “anger and frustration…. that there was nothing here for us.” She was met with doubt: “people said we couldn’t do it…it was going to be difficult for us to cast because there wasn’t….any Polynesian actors… and… it was like “yeah… well …we’ll have to make a start then won’t we?” People were sceptical towards Simei-Barton, noting the lack of Pasifika actors due to there not being a precedent of theatre in Auckland that represented Pacific communities. She was driven to set such a precedent and provide Pasifika the opportunity to be increasingly involved in Auckland acting and theatre.

Justine Simei-Barton, photo by Sally Tagg, New Zealand Listener, 26th August 1989, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-05879

The University became the site of where she brought together the first actors in Pacific Theatre in 1987: “we just put out a general audition (on campus).” As it turned out, Simei-Barton did not have trouble finding and casting actors as people had told her she would, “Oh we had hundreds of people audition… Polynesian students… A lot of them had just come through just out of curiosity.” She thought this curiosity stemmed from how it was “so unusual” to see a piece of theatre calling for a large Pasifika cast. Simei-Barton ended up directing around twenty five actors, and Feiva / Favour was performed in 1988 at the University’s Maidment Little Theatre to “full houses…and that was without even publicising it. That was basically just word of mouth.” The Pasifika actors likely felt immensely empowered by taking the Auckland stage, and any Pasifika audience members who made up the “full houses” may have felt similarly inspired.

“The Ocean That Surrounds Us”: Pacific Theatre’s Contribution

After their inaugural performance, Pacific Theatre went on to perform a number of shows. Justine Simei-Barton remained as the director, and her husband, Paul, wrote scripts for the company. In a joint statement, they described how they researched and based many of their productions on “Polynesian mythology… and oral tradition… the myths, legends, folk tales, songs, poems, and performance traditions [which] reveal the brilliance of Polynesian culture…[it is] a heritage that arose out of the ocean that surrounds us [Aotearoa New Zealand].” With regard to how she directed the actors to perform, Simei-Barton drew from “numerous Polynesian performance and entertainment traditions.” They brought the “vitality” of these traditions and facets of Pasifika cultures “into a modern theatrical context.”

Pacific Theatre also brought them into a school context, providing a cultural education and engaging younger generations with Pacific stories. Their shows toured around North Island schools, with a special focus on connecting with South Auckland schools, where there were mainly Māori and Pasifika students. Simei-Barton recalled how she and the actors felt a responsibility to their families and Pacific communities, to do well in portraying facets of their cultures to audiences: “it was like their mana on the line as well.” Simei-Barton and Pacific Theatre, made a significant contribution to increasing representation of and respect for the cultures of Auckland’s Pacific communities.

Pacific Theatre Logo, Robeson – Song of Freedom programme, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-05879

Mercury Theatre and Pacific Theatre: What They Could Afford to Do

Aside from their differences in attitudes and beliefs, with the Mercury viewing English theatre as an ideal influence and Justine Simei-Barton founding her company because she saw Pasifika cultures as an untapped source of enrichment for Auckland theatre, the Mercury and Pacific Theatre’s contrasting approaches could also be attributed to their contrasting financial situations.

The Mercury was a professional company, with its own city theatre, and experienced directors and actors recruited locally or from abroad. In setting up the Mercury, the Auckland Theatre Trust had implemented an ambitious fundraising campaign through numerous advertisements, and acquired funding from the Auckland City Council, raising $180,000 in total. The Mercury sought to continue this financial success, by filling its theatre seats, making profit from its shows, and paying its director, actors and stage crew. By contrast, Pacific Theatre was an amateur company. Its first actors were students from the University of Auckland campus. Most of them had minimal theatre experience, because of the limited opportunities given to Pasifika in this sphere, before they made their own opportunities through forming Pacific Theatre. Justine Simei-Barton remembered rehearsing in small community halls, or sometimes in her lounge, if the play had a small cast. They put their shows on voluntarily; Simei-Barton recalled how the company’s actors were rarely paid, only when enough money came through from ticket sales. They often relied on funding from their families and communities to keep running.

As the Auckland Star observed about the Mercury in December, 1968: “Artists should live dangerously, said Nietzche, and nobody could say that the Mercury has been doing that… a full professional theatre does not invalidate the argument that amateur theatre should be able to run alongside the Mercury… doing plays which the Mercury can’t afford to risk.” Simei-Barton’s company demonstrated the power a grassroots or amateur theatre company could possess in not being bound to only producing safe shows that they could “afford” to do. Although they had fewer resources, they could be more experimental, and trailblazing in comparison to the established professional companies of the time. Mercury Theatre remained in a cultural status quo, holding on to English theatre, whereas Pacific Theatre contributed to bringing about increased Pasifika representation, cultural diversification, and evolution in Auckland theatre.

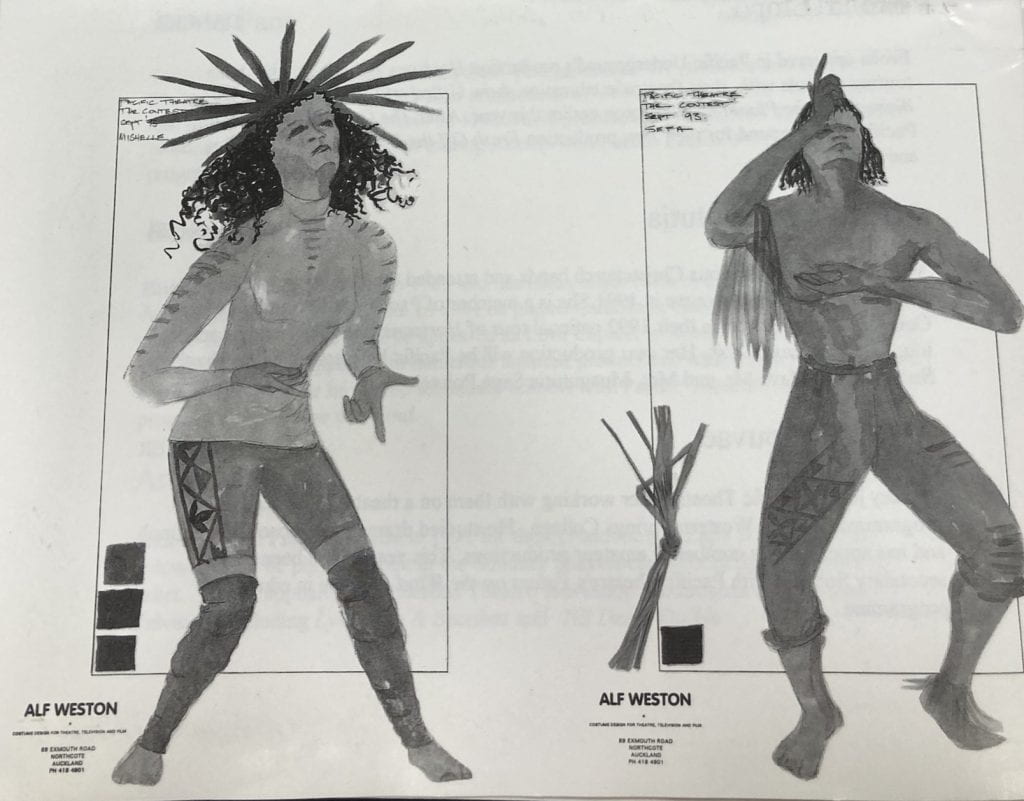

Costume designs from a Pacific Theatre production. The Contest, programme, by Paul Simei-Barton, Directed by Justine Simei-Barton, September, 1993, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-05879.

Closing Reflection

Mercury Theatre and Pacific Theatre provide compelling case studies of cultural conflicts and changes in late 1960s-80s Auckland theatre. The companies’ trajectories also reflect broader developments and challenges that Auckland as a city has encountered as it tried to find its cultural identity. Like the Mercury, how has Auckland held on and deferred to English tradition due to the legacy of colonisation? How insecure or unsure have members of Auckland’s community felt about trying to develop a local culture that does not defer to the city’s colonial roots? How have movements like Pacific Theatre pushed Auckland to recognise and respect its Pacific communities and the importance of representation? I hope this article demonstrates the value of utilising our theatre history to explore cultural developments and questions that have been central to Auckland over time.

Elizabeth McRae and Justine Simei-Barton’s perspectives were essential to this piece. My next article will continue to draw from the first-hand experiences of Auckland acting women that Hyland interviewed, providing insight into the empowered and yet conflicted and challenged nature of 1980s feminist theatre in Auckland.