Part Five

“If You Would Be an Actress”: Auckland Women’s Personal Experiences of the Pressures of an Acting Career

Part Four

Feminist Theatre Takes the Stage in 1980s Auckland

by Anna McCardle*

“If you would be an actress you must make up your mind for hard work, for there is no other calling so exacting in its demands.”

Writing for the New Zealand Graphic in 1897, this unnamed columnist thought the acting women of their time had immensely challenging jobs. Although the acting women I have researched worked nearly a century later, I think this quote would still resonate with them; their acting careers certainly came with exacting demands. This article will explore how the women Jean Hyland interviewed faced significant pressures as late 1960s-1980s Auckland acting women, including managing the demands of being working mothers, striving to meet strict beauty standards, and grappling with the feminist push to call themselves actors instead of actresses.

In my previous articles, I have used Hyland’s Acting Women In Auckland oral history collection to explore the perspectives of acting women on key professional, cultural and feminist facets of late 1960s-1980s Auckland theatre. However, in this final article, I would like to focus on the women themselves, for they are at the heart of this story.

I will draw upon the personal experiences of four acting women Hyland interviewed: Elizabeth McRae, who acted with Mercury Theatre from its first show in 1968, Justine Simei-Barton, who founded Auckland’s Pacific Theatre Company in 1987, and Andrea Kelland and Linda Cartwright who both acted with Theatre Corporate in the 1970s. While I am exploring the lives of four women in the Auckland acting scene, I believe that taking a microhistory approach in examining their perspectives gives us a compelling lens into the pressures of being an acting woman in the late 1960s-80s, and also the wider issues facing Auckland women in this period.

Balancing Motherhood with Acting

Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland and Justine Simei-Barton were not only acting women, but also mothers who coped with the pressure of balancing work and raising children. Linda Cartwright did not have children, and without extensively explaining her own situation, said she was “really sympathetic” towards acting women she knew who went through “quite a hard time” handling the dual demands of work and motherhood: “That wasn’t my experience, I should imagine it would have been darned hard.”

A Bit More than Icing: Elizabeth McRae’s Experience

When Elizabeth McRae performed in a 1959 production of Under Milk Wood at St Andrew’s Hall, Symonds Street, she was around five months pregnant, and remembered being described in one of the reviews as “a very fertile village floozy.” Such a comment captures the shock, scrutiny, sensationalising, and fascination that could be directed towards working mothers. McRae’s desire to act was at odds with the conventional housewife-life that society prescribed for a woman with children and a husband: “I didn’t have to do it [act] because in those days… you could run a family on one income, so my husband was earning enough for me not to have to earn money. It was just sort of icing I suppose, a bit more than icing.”

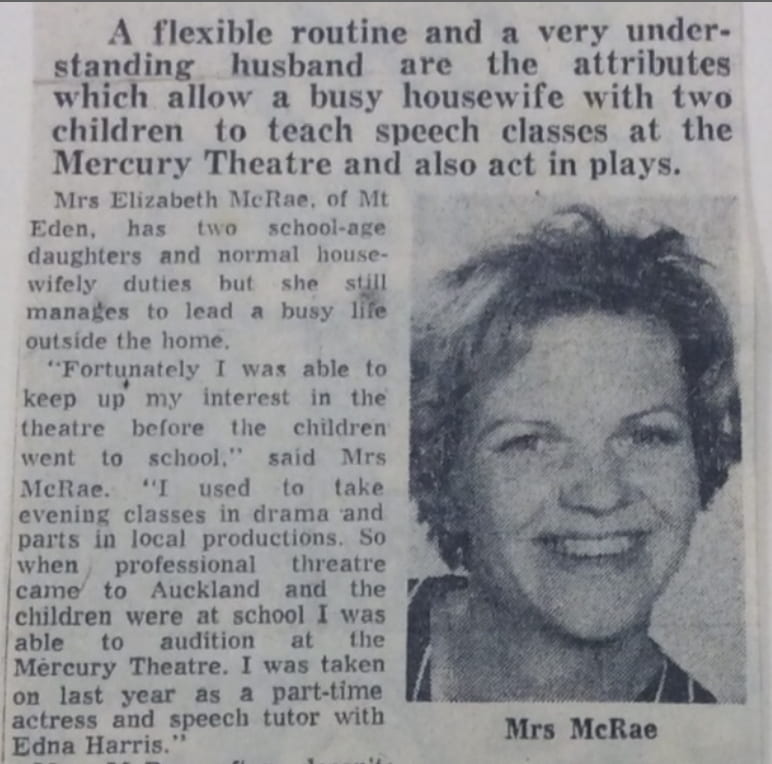

1969 article marvelling at “Mrs McRae’s” ability to be a working mother. It only gives credit to her “flexible routine” and “very understanding husband,” and does not acknowledge McRae’s own tenacity. Mercury Theatre scrapbook, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection, https://digitalnz.org/records/32983639/mercury-theatre-scrapbook

Whilst caring for her two children, McRae could not work full time at the Mercury Theatre, but she still “did a number of plays.” Donald McRae, who was on Mercury Theatre’s Auckland Theatre Trust Board, was supportive of her work: “He was working full time in the city so it wasn’t as though we could share childminding… But he would collect them when he came home from work when I was working at night.” How many Auckland men were like him and supported their wives if they desired to work, despite it being more traditional for them to always stay at home and look after their children?

McRae acknowledged the difficulty of how “There wasn’t a culture of nannies, and there wasn’t a culture of day care… you looked after your own kids.” She relied on a support system of women she knew: “you used your mother or your friends… we swapped children around quite a bit. So that would always happen when I was rehearsing.”

“The Show Must Go On”: Andrea Kelland’s Experience

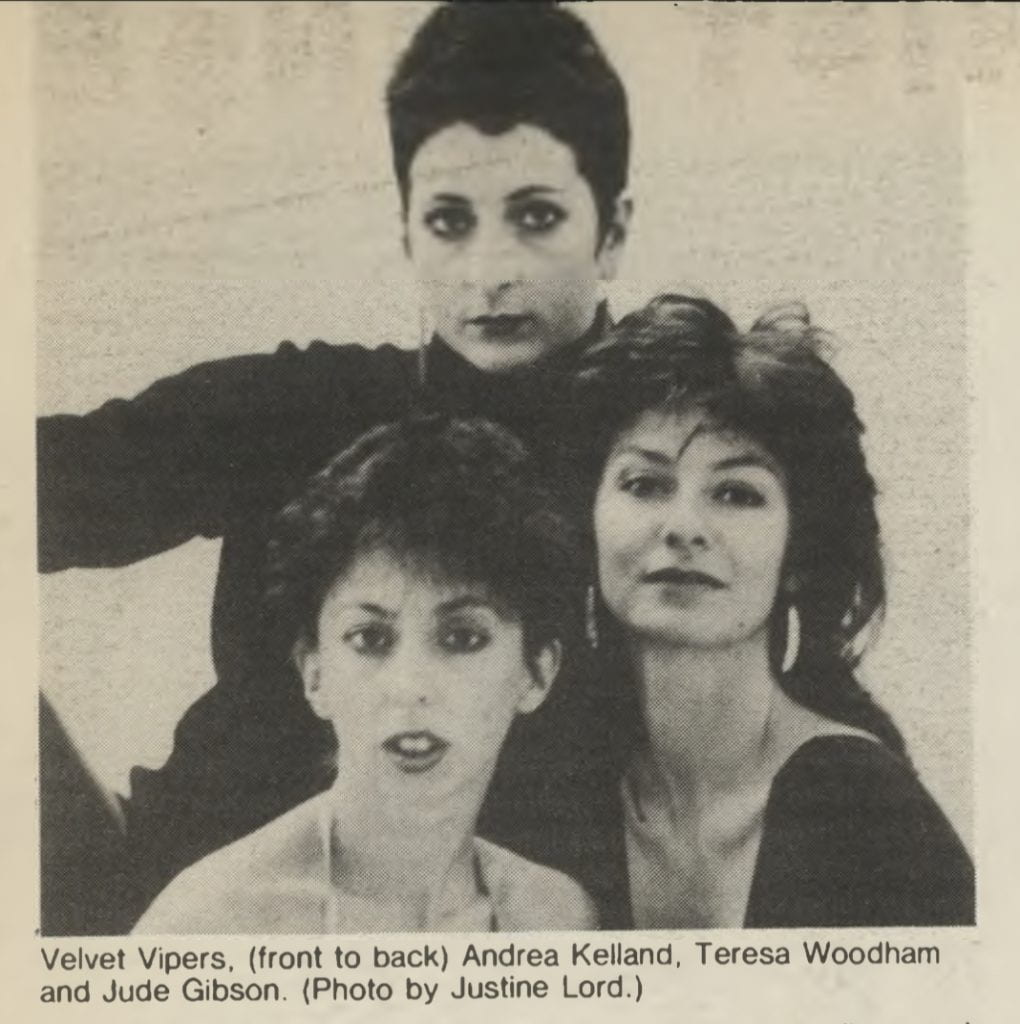

In 1982, just six weeks after Andrea Kelland gave birth to her child, she toured around the North Island in a Mercury show, Once a Catholic. She played one of the schoolgirls who were almost always onstage at the same time as the Nuns were backstage. There was always someone to mind her baby while she was performing.

Kelland found simultaneously being a mother and an actor challenging, particularly because she was a single parent. However, she persevered: “It was hard, but you know, the show must go on. It was just such a mantra.” She encountered similar difficulties to Elizabeth McRae in accessing child-care services: “I can remember nights where it is seven o’clock and I still haven’t got a babysitter and I’m going to have to take him into the theatre.”

Kelland found her parents, partners, and the Domestic Purposes Benefit (social welfare allowance for single parents) to be of helpful support.

Creating a Welcoming Environment: Justine Simei-Barton’s Experience

Justine Simei-Barton was immensely busy as she balanced being a mother and director at the Auckland Pacific Theatre Company. Her husband, Paul Simei-Barton, was also involved with the Company. Simei-Barton would take their baby and young child along when Pacific Theatre performed at Auckland and North Island schools, which made things crowded: “we [Simei-Barton, the children, and the Company actors] used to tour in my station wagon with…all our props and our costumes.”

A key factor in how Simei-Barton managed was highlighted in an interview question Hyland posed to her: “The theatre you were creating… was open to children being there?” Simei Barton affirmed Hyland’s interpretation: “I can’t have my kid… and not allow any other kids to come through.” By creating a welcoming environment in her theatre, Simei-Barton gave herself and members of her company the ability to look after their children as they worked.

Justine Simei Barton, photo by Sally Tagg, New Zealand Listener, 26th August 1989, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-05879

Elizabeth McRae felt that during her acting career, “women’s work was regarded as less important” because of the expectation that women would either stay in their jobs, or “leave and have babies.” Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland and Justine Simei-Barton certainly challenged that expectation. They harnessed their determination and support systems, and stayed in their work as Auckland acting women. These women’s accounts reflect the pressures endured by working mothers in the late 1960s-1980s. This was an era where it was gradually becoming increasingly common for women to remain in their jobs after having children, and this change would have been difficult for some people to comprehend or accept. Many Auckland mothers likely grappled with the same societal expectation that McRae spoke of; that they should leave their work once they had a baby, and adhere to the more traditional path of being a housewife.

McRae and Kelland’s memories of finding it difficult to access childcare services points to how support for working mothers could be quite limited in Auckland, compared to around 1,652 childcare services available now. These acting women had to utilise any alternative help they could find, sharing childcare responsibilities with their partner, swapping children around with other mothers they were friends with, social welfare payments, or establishing a child-friendly theatre. Other Auckland working mothers likely had to be similarly inventive and persevering in accessing every person or resource available to help.

Moreover, these acting women’s experiences also reflect the passion and dedication working mothers can have for their jobs. Cartwright acknowledged the difficulties her colleagues faced as mothers in her “I should imagine it would have been darned hard” comment. Balancing work and motherhood can be immensely challenging and exhausting, however many Auckland women who chose this path likely felt that the energy they expended was worth it to keep working in a career that was important to them. McRae, Kelland and Simei-Barton were committed to their theatre work; they enjoyed and regarded the craft of bringing a show to life for an audience as significant. They were willing to face the pressure of pursuing this career path, alongside raising their children. They loved their children and their work, and were determined to devote themselves to both.

Appearance: How It Shaped Acting Women’s Careers

While Justine Simei-Barton did not directly address the effect her appearance had on her theatre-work in her interview, Andrea Kelland, Elizabeth McRae and Linda Cartwright all discussed how they were conscious of the importance of their looks as they worked in Auckland theatre. As Cartwright summarised, “Your physical attributes do help or hinder your acting career.” She provides a detailed account of the pressure she felt to pay attention to nearly every single facet of her looks.

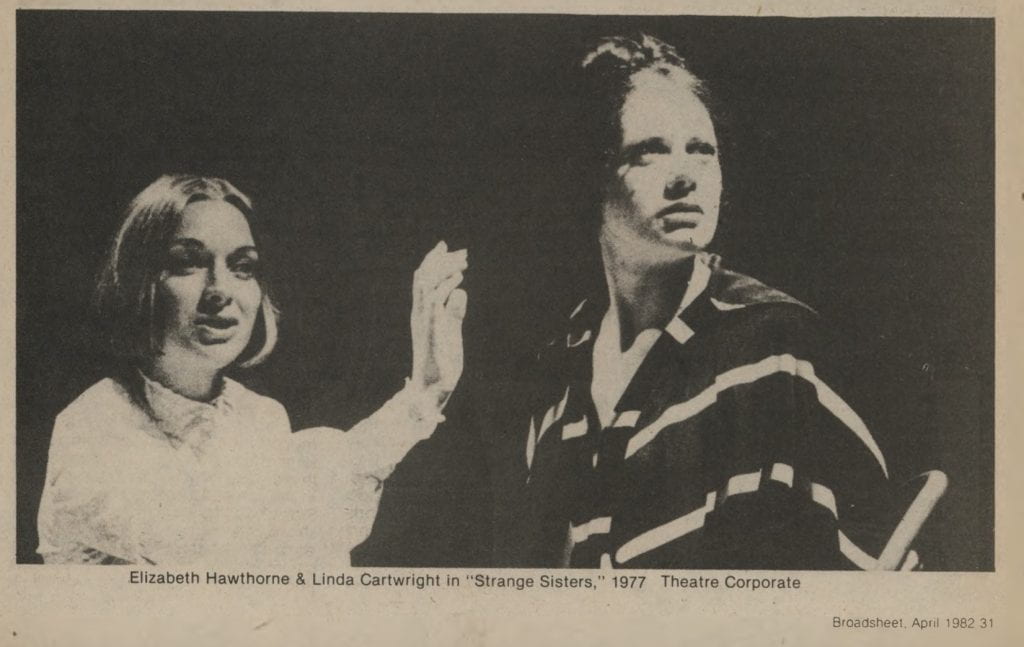

Cartwright watched her weight: “we were very careful, all of us… if I’d seen that I’d put on a few pounds I would try to get rid of them… if you were overweight you probably stood less chance of getting work.” She learned “makeup tricks” to enhance her facial features, which she felt were otherwise “sort of average.” When a director demanded she play a role without makeup in a 1977 Theatre Corporate show, Cartwright drank lemon juice “like crazy” to keep her skin clear, and still covertly wore false eyelashes onstage. She also “assiduously” dyed her hair red, because the colour was a “good selling point.” She could stand out and be “billed as Theatre Corporate’s resident redhead and I knew it looked good under the lights.”

Adding onto the list of face, weight and hair colour, Kelland was conscious of the importance of height for playing heroines. She thought that if she could have added “another three inches,” she would have been “more in line for middle of the road heroines.”

Image from Broadsheet, no. 109 (May 1983): 33. Broadsheet- New Zealand’s feminist magazine 1972 – 1997 collection, University of Auckland, https://broadsheet.auckland.ac.nz/

Beyond specific physical features, at around the age of 18, McRae received a blunt judgement of her overall appearance by her acting teacher: “you won’t come into your own until you’re older, you’re not a ingénue.” Indeed, rather than being cast as ingénues (young, innocent, and beautiful girls), McRae felt she was given more “character work”; roles where portraying an eccentric or striking personality is more important than appearance.

McRae’s teacher thought that she would “come into her own” when she was older because there was, and still is, a tendency for older women to be given character work. Kelland reflected on how she was able to play ingénues in her early 1970s days at Theatre Corporate, whereas when her interview was recorded in 2005: “I’m old enough to play… grandmothers and witches and quite interesting [characters]… where it doesn’t matter that you’re not kind of drop dead gorgeous any more.”

As Auckland acting women, Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland and Linda Cartwright endured the pressure to constantly monitor their looks, because judgements made about their appearances could determine the roles they were cast in and the trajectory of their careers. Their accounts help us understand how Auckland women’s appearances decades ago could be subjected to strict beauty standards. Moreover, these standards are likely continuous and still affecting contemporary Auckland women. The expectations McRae, Kelland and Cartwright described for how an acting woman needed to look to play an ingénue or heroine, are similar to attributes perpetuated to be conventionally attractive in women today, such as having clear skin, a lower weight, and being youthful. The glorification of these features has often been underpinned by disparaging societal attitudes towards ageing and the fat body. Women have historically been, and still are, pressured to make their appearance fit a restrictive mould deemed to be ‘palatable’ by society and observers like casting directors and theatre audiences as McRae, Kelland and Cartwright experienced.

Actor vs Actress: What’s in a Name?

‘Actress’ has been a contentious term. As Linda Cartwright recalled, “everyone used to be talked of as actor and actress,” but language changed with the rise of second wave feminism in 1970s and 1980s Auckland: “Suddenly you weren’t allowed to do that any more… the buzz around town was oh no it was much better [to call women actors, not actresses], because it was a whole feminist thing.” Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland, Linda Cartwright and Justine Simei-Barton held diverse perspectives on the feminist pressure to call themselves ‘actors.’

McRae felt that actress was “demeaning.” She perceived that the ‘OR’ ending of terms like actor or doctor was “not a male ending”; it described someone who did their job, “a do-er.” Men having sole claim over the word was unfair: “we [men and women] all do this job of ‘acting.’” In McRae’s opinion, “nobody would call themselves a ‘poetess’… you don’t have [a] ‘doctress.”’ Kelland held a similar perspective: “My bandwagon was ‘we don’t call people doctresses or lawyeresses, so if I am a professional actor I’m just an actor. My gender has very little to do with it.”’

By contrast, Cartwright preferred actress: “I’m as feminist as everyone else, yes, but I just don’t happen to agree… I don’t feel that there’s anything awful about being an actress.” She respected how actress conveyed the long history of acting women who came before her: “historically, people have been known as actresses and I think it’s a bit of a salute to them too. These women who are rather unconventional way back… in Jacobean times… who were the great actresses.” Antithetical to Kelland’s feeling that gender had “little to do with her work,” Cartwright appreciated that actress explicitly acknowledged women in the profession: “We are women who act and we’re not men.”

Linda Cartwright (right) performing in a 1977 Theatre Corporate production, “Strange Sisters” with Elizabeth Hawthorne (left) Broadsheet, no. 98 (April 1982): 31. Broadsheet- New Zealand’s feminist magazine 1972 – 1997 collection, University of Auckland, https://broadsheet.auckland.ac.nz/

Simei-Barton did not seem to think there was any feminist implication in the choice between actor or actress. She called herself an actor because “I just like the sound of it… There’s nothing political or deep about it.” When Hyland questioned her on whether she perceived any “effects or differences” in choosing actor over actress, she said she did not. For her, it was just a simple preference in language.

Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland, Linda Cartwright and Justine Simei-Barton faced a feminist pressure to call themselves actors instead of actresses, for as Cartwright recalled, it was “the buzz around town” in 1970s-1980s Auckland. This change in preferred terminology reflected how second wave feminism was affecting and reshaping standards within the Auckland acting profession, even right down to the language it used. Despite not being as obvious a social pressure as motherhood or beauty standards, actress and actor becoming politically charged terms pushed these women to have a view on how they labelled themselves and their careers, and argue for it. McRae and Kelland followed the feminist current in favour of actor, but Cartwright felt she had to defend herself as being no less of a feminist compared to “everyone else” just because she preferred actress. Simei-Barton similarly felt she needed to justify why she did not view the choice in language as politically deep. Although second wave feminism was empowering in many respects, Auckland women must have been drained by having to constantly form, defend, and debate opinions about their careers and other facets of their life when they became politicised by the movement.

Closing Reflection

Managing the demands of being working mothers, conforming to strict beauty standards, and facing the feminist demands, such as the push to call themselves actors instead of actresses, are compelling examples of the challenges Elizabeth McRae, Andrea Kelland, Linda Cartwright and Justine Simei-Barton faced as they pursued acting in the late 1960s-1980s. Their experiences also reflect significant issues that transcended an acting woman’s experience: the lack of value placed on domestic work, beauty trends, the pressure women endured to defend their opinions or choices about their lives and careers when they were politicised by feminism, and the contentious nature of the language women used to label themselves or their careers. These were social pressures that many Auckland women endured.

Overall, it has been a privilege to use Hyland’s rich oral history interviews, and hear the voices of these Auckland acting women talk about their lives and careers. They are at the heart of my research and their perspectives have been instrumental in informing my articles’ coverage of late 1960s-80s Auckland theatre.

Alongside this final article’s focus on the pressures Auckland acting women faced in their work, I have been able to explore the late 1960s and early 1970s emergence of Auckland professional theatre. It initiated a vibrant and active era in performing arts, with professional companies like the Mercury or Theatre Corporate staging a myriad of shows in the city or touring schools. Auckland acting women’s careers were significantly affected by being able to join these emergent companies, where they encountered invigorating yet challenging work conditions.

Auckland theatre experienced cultural conflicts and evolutions throughout the late 1960s-1980s, with Mercury Theatre frequently deferring to the influence of English theatre over supporting the increasing number of plays being written by New Zealand playwrights, and Justine Simei-Barton moving to heighten representation of Auckland’s Pacific communities through founding her own theatre company. These instances reflect how Auckland grappled with developing a local culture that did not defer to the city’s colonial English roots and increasing its representation of its culturally diverse population in spheres like the performing arts.

In the 1980s, Auckland’s feminist theatre empowered women artists and audiences. Yet it also grappled with challenges and conflicts. McRae and Kelland’s feminist theatre productions appeared to receive limited support from Mercury Theatre, who possibly did not believe in their ability to attract large audiences and commercial success. They also encountered internal divisions within Auckland’s second wave feminist movement, such as between heterosexual and lesbian feminists, or a conflict of interpretation over a play’s portrayal of women’s struggles.

Hyland interviewed 37 Auckland women who worked in the acting profession from the 1920s onwards. She expertly shaped the interviews to draw out stories from the acting women about their fascinating careers and lives. There is a great deal more material in her collection that I could have explored, and that future research should explore. I hope that my articles have provided a compelling lens into Hyland’s research, the fascinating experiences and perspectives of Auckland acting women, and the richness and complexity of the history of Auckland theatre.