Part One

Auckland’s Sportswomen: a Conduit for Social Tension

Part Four

Marching: Aesthetics and Uniformity

by Katia Kennedy*

“Somehow, whenever women try to do something active instead of crocheting antimacassars, they always have to face a great deal of derision.” – the Ladies Mirror

Women’s sport has long been a subject of contention. Since the late 1880s, Auckland sportswomen have faced backlash, criticism and a general lack of support within their chosen sports. Where women’s sports have developed immensely since then, women’s involvement in male-dominated sports remained contentious. The conversations that surrounded sportswomen between the 1880s – 1980s – the criticism, support and backlash alike – make it clear that sports were not only a pastime women had to fight to enjoy, but also a conduit through which we can view the ever-evolving societal views involving women.

Auckland women have long been involved in outdoor activities. This was particularly true and well documented for white, rural, settler communities. By the late 1880s this had begun to extend to organised sports. For most women, this was a newfound freedom and their active lifestyle was routinely romanticized. An example of this is the poem The Girls of Ninety-One, published in the Ladies’ Mirror that describes the active nature of girls in 1891:

“They tell me ‘twas the fashion,

O, long and long ago,

For girls to look like lilies white,

And sit at home and sew.

Forth strode their sturdy brothers

On many a gallant quest:

But the maids behind the lattice

Their weary souls possessed.

To-day the times have altered,

And pretty Kate and Nell

Are playing merry tennis—

In sooth they do it well.

They ride across the country,

They climb the mountain side,

And with oars that feather lightly

Along the rivers glide.”

– The Girls of Ninety-One, Ladies’ Mirror.

This sentiment was not shared by all, and around the turn of the century, when women began to participate in organised sports, concerned outcries for their health and their image became increasingly vocal. This attempt to control how women moved their bodies did not stop women from playing sports but it did create challenges and would shape the trajectory of women’s sport over the coming century.

Despite the criticism and negative attitude that developed towards women’s sports, women were very actively involved in physical activities for the time. While not necessarily a ‘sporting society,’ 1890s Auckland—especially rural areas—were very active. Picnics and carnivals were relatively frequent, with girls and young women competing in races and other outdoor activities alongside boys and young men. It was also common for women and men to play casual games of hockey, tennis and badminton together. When organised clubs for sports like cricket became common, women did not compete alongside the men, but were still involved in the administration. Women and children attended cricket matches, turning them into events akin to picnics and staple events in society. Dances and balls were often held at the end of each season and women were among the attendees. Despite not participating in the sport itself, women had made their presence amongst cricket club activities undeniable. Unlike with cricket, tennis became a popular organised sport between both men and women. It was so popular in fact, that in Alfriston, the original members of the tennis club were mainly women. In 1891, the club had grown to an almost even number of men and women because: “the sterner sex, allured no doubt, by the graceful flutter of feminine garments as the wearers flitted to and fro, racquets in hand.”

Around the turn of the century, from the 1880s – 1920s, women’s sporting organisations were beginning to emerge. It was around this time that the social attitude towards women in sport began to shift.

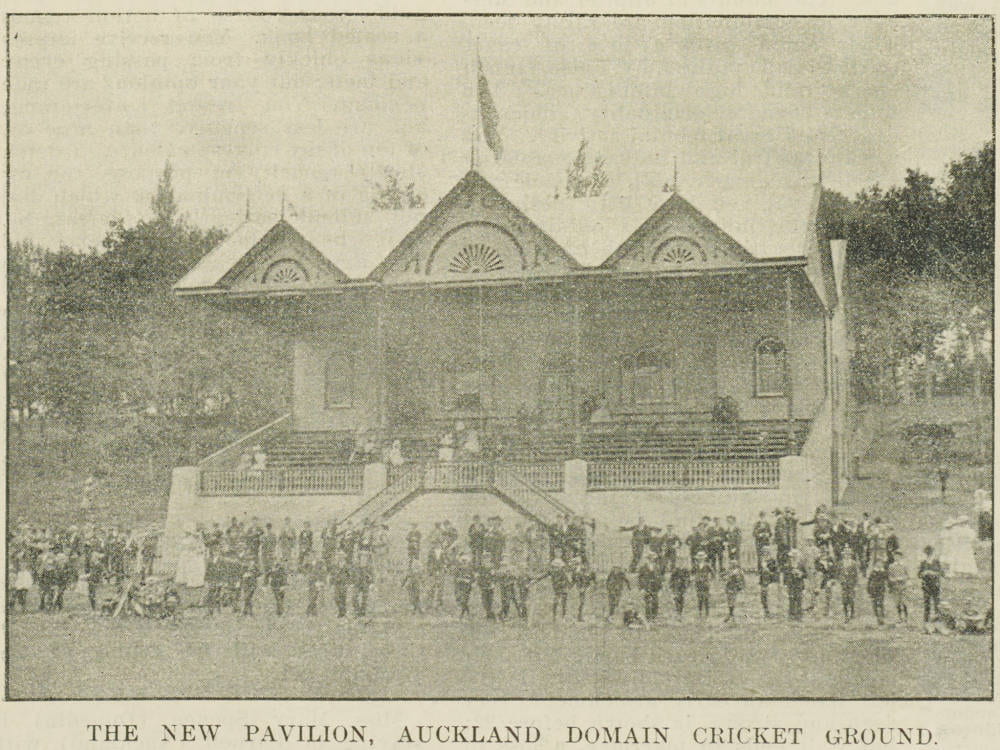

Figure 1: Male cricket players in front of the Auckland Domain Pavilion, women and children spectators can be seen in the stands. (The New Zealand Graphic. The New Pavilion, Auckland Domain Cricket Ground. December 17, 1898. NZ Graphic Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/116576.)

As women began to participate in organised sports, concerns for their health became more vocal. A common trepidation was that young girls, who played strenuous outdoor sports, were at risk of becoming “too healthy” and that their bodies were not built to deal with such a strain. There were also concerns that the athletic culture girls were becoming increasingly accustomed to would make childbirth nigh impossible because they would develop a “kind of male pelvis.” These health concerns were not shared by everyone. There were some who believed that this “new outdoor life of women and girls” was positive, healthy and should be praised further. Many sports such as cycling, tennis and golf, in which women excelled, were also thought to be beneficial despite critics and naysayers.

While the active, ‘outdoorsy’ lifestyle was generally approved by many, those who defended it still acquiesced that some sports were simply not fit for women. In 1923, an anonymous ‘Lady Doctor’ defended the health benefits of sport for women, including building muscle, strength and developing a healthy appetite. However, she also affirmed that sports or any form of exercise that involved “twisting or sudden wrenches” was bad for women. Her examples included hockey, jumping and long-distance walking. Rowing was often condemned for women, on the account of the strain it placed on the heart.

Rugby (or football) was also seriously condemned, not just for the unladylike concept of women playing rugby but also for financial reasons – women’s rugby would not draw a crowd. In 1891, a proposed tour of the Auckland women’s rugby team was heavily condemned in the Auckland Star. The article thoroughly criticised the proposal stating:

“[…] but there are some things for which women are constitutionally unfitted, and which are essentially unwomanly. A travelling football team composed of girls appears to us to be of this character. Moreover, making every allowance for the vitiated tastes in the popular craving for amusement, we cannot conceive of either men or women who have sisters of their own being attracted to such a spectacle, or encouraging a number of girls to forsake womanly employments for the purpose of entering upon the life of an itinerant footballer.”

The article predicted that if the tour was to go ahead it would end in financial disaster. Nita Webbe, the manager and promoter of the team, wrote back with a scathing response. She asked the anonymous author of the article what part of the proposed tour he considered unwomanly, “the travelling part of the scheme or the footballing?” Webbe continued, not only to condemn the idea that playing sport was unwomanly, but to broadly encompass the limitations she and the rest of the women in Auckland suffered from on account of their sex. Webbe countered with examples of athletics and gymnastics both at one point being considered ‘unladylike’ and the rapidly changing nature of these sports and predicted that rugby will follow in these footsteps.

Indeed, women’s rugby has advanced considerably since then into today (see article 5 for more discussion on developments in women’s rugby). At the close of the nineteenth century, “It was then the ‘correct thing’ for a young lady to lounge about, delicate and pale, and slim; but everywhere now that girl is considered the most ladylike who takes her exercise and enjoys the consequent good appetite and colour.”

Comments like this– concerned with the appearance of women, particularly with the paleness of their skin– imply that Pakeha women stood front and centre of this debate. Māori women and women of other ethnicities are not mentioned. In turn, it also suggests that Pakeha women were the only ‘proper women’ society accepted during the 1880s. Unfortunately, as we will see in later articles, this sentiment remained in the background of discussions involving women’s sport for much of the 20th century.

Despite Webbe’s response being published (and including quite radical claims for the time) was surprising. However, the Auckland Star published it with a disclaimer stating that Webbe’s response did not mean that the Star shared her opinions. It also acknowledged that despite the talent some women on the rugby team possessed “popular taste is still elevated enough to insist upon grace and beauty in the exhibitions by female athletes.”

During the early 20th century, women’s sports can be sorted into three different categories. The first were sports that both women and men played (sometimes together), such as tennis and basketball. Basketball gained popularity in Auckland, on account that the teams could consist of mixed sexes. The non-contact nature of the game meant that both men and women could play together without “any fear of roughness being introduced.” The second were sports that were generally accepted as ‘feminine.’ Sports like hockey, netball, dancing and marching fell into this category and generally received the most public support. The third were the ‘masculine’ sports or sports that were traditionally dominated by men. This included rugby, football and cricket. These sports received a lot of public disapproval and were often accompanied by criticism of the women’s skills in comparison to men.

Figure 2: A women’s doubles match at Clevedon Tennis Club. (David Bryan. Women Playing Tennis, Clevedon, ca 1914. 1914. Footprints Colelction. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/38948/rec/1.)

It appears to be a common theme that whether sports were considered ‘unwomanly’ by some, or praised by others, they were expected to be only temporary pastimes until a girl found a husband and commenced the domestic roles expected of her. Some sports were criticized because a woman did not look nice whilst playing, preventing them from piquing a man’s interest. Women’s cricket in 1890 was deemed ‘ungraceful’ and in a letter to the editor of the New Zealand Graphic it was stated that “no woman looks nice when she is running, and if they could only see themselves no girls would play cricket.”

Sports that interfered with ‘womanly duties’ were also frowned upon. Even those defending women’s sport tended to see a woman’s participation in a sport as temporary and something that would end after marriage. A recurring argument in support of women’s sport was that girls and young women would be more likely to find husbands at sporting events than “in the confines of her mother’s drawing-room.” Sports were even expected to prepare young girls for their “domestic duties” later in life—despite the ‘health concerns’ that a girl may over-strain herself playing. Overall at the turn of the twentieth century, women’s participation in sport was linked to her ability and worth as an attractive female, a wife, and domestic duties. There was minimal discussion around the personal satisfaction or enjoyment that women in Auckland may experience playing sport which clearly was not deemed important. Despite this, the personal enjoyment of Auckland’s sportswomen is evident through the many photos that will be showcased in later articles.

Figure 3: A group portrait of the Waiuku Ladies Hockey Team, including coaches, chaperones and mascots. (G. Jasper. Women’s Hockey Team, Waiuku, 1921. 1921. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/37909/rec/1.)

As the 20th century progressed women attempting to play such sports began to increasingly be seen as ‘invading’ or ‘taking over’ the man’s sport. This invasion rhetoric – used to criticise women playing certain sports – where women were entering spaces designated by society as male only, reflected the gender tension during this period. This tension stemmed from women gaining more freedom due to economic and wartime pressures. The classic example being domestic containment; women being ushered out of workplaces (traditionally filled by men) and back into the domestic sphere after the Second World War. This resentment was not easily left behind (some might argue that it still isn’t) and followed women as far as the 1940s. The statements were usually broad and harsh:

“There are few phases of sport which man can call his own. Women have invaded the pastures once particularly his. They run, they swim, they ride, they play cricket, golf and even football, they box and they wrestle.”

Despite women being active in outdoor activities and sports organisations from as early as the 1880s, they did not participate without garnering criticism. This only became more vocal when women started to form and join their own organised sports. Concerns for their health and future (as socially sanctioned wives and mothers) gained further attention from disapproving factions of Auckland’s society. But these sports continued to gain popularity regardless of this criticism. My next three articles will explore the difference in the development between traditionally male and female sports by using cricket and marching as case studies.