Part Five

How Auckland Ditched Rail for Roads and Rubber Tyres:

Conclusions

Part One

The good old trams

Part Two

Trams out; trolleybuses in

Part Three

The tube

Part Four

Motorway mania

by Sam Turner-O’Keeffe*

Over the last four articles, we have traipsed through the halls of post-war Auckland’s transportation history. We have learned about the city’s replacement of its trams with trolleybuses. We have discovered that its motorways were constructed at the expense of extensive railway improvements. We have, in both cases, analysed the reasons why those events unfolded. However, the biggest question is yet to be answered. Did those decisions actually intensify Auckland’s congestion woes? Had the city’s trams been restored, or its railways improved, would commuting through Auckland be as frustrating and inefficient as it is today?

Congestion on the Northwestern Motorway, 1989. Was this the result of either of the two decisions we have covered? (Photograph by Miles Hargest. November 1989. Reference Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 273-HAR058-11. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/100142.)

Before answering this question, some clarification is needed. It would be ridiculous to argue that two decisions made between seventy and eighty years ago were the sole catalysts for Auckland’s contemporary congestion struggles. Auckland is a big city. It is undeniable, then, that a range of different factors from the past shaped Auckland’s present-day predicament. The more appropriate question concerns how influential the two decisions we have investigated might have been in driving congestion, if at all.

Further, it must be acknowledged that this analysis is speculation guided by evidence. It is not an objective assessment of the reality. Nobody really knows how Auckland would have fared, had history panned out differently.

Trolleybuses: a mistake?

We will begin with the switch from trams to trolleybuses. Did this have any direct influence on Auckland’s congestion woes? It is certainly possible to argue that it did.

Firstly, some Aucklanders simply preferred tram services over trolleybus services. One reason for this was that trolleybus (and motor bus) termini were scattered across different inner-city streets, whereas their tram predecessors had all convened at Queen Street. The corresponding effect was summed up well in an April 1956 article from the Auckland Star: ‘people either don’t know where buses start from, or, if they do, it is inconvenient for them… they grew up with the knowledge that “you can get a tram in Queen Street.” That was all they needed to know.’ In short, the switch from trams to trolleybuses had made public transport confusing to use. When facing off against the indomitable pull of the private motor vehicle, this was sure to alienate passengers.

Accompanying this was a widely-held fondness for the old trams. Numerous other Auckland Star articles noted how passengers usually fought between themselves to board the old trams, where they would sit pressed together on cramped wooden benches and smoke whenever they wished to (a luxury afforded only to the driver on trolleybuses). These factors gave the trams a ‘clumsy but lovable’ air, being ‘matey’ and ‘working-class’. The sleek newness of the trolleybuses, by contrast, was ultimately described as having been an unnecessary addition. All the switch to trolleybuses did, for some, was strip Auckland’s public transport of its soul.

However, there is also evidence to suggest that many other Aucklanders liked the trolleybus services more than the old trams. Consequently, while the switch from trams to trolleybuses probably drove some disgruntled commuters away to their motor vehicles, this certainly did not apply across the board. The impact on rising congestion by the removal of trams, then, was probably limited.

Secondly, the way the switch from trams to trolleybuses was undertaken may have intensified congestion. Because Auckland’s tramways were gradually phased out of operation, some continued to run in the city until 1956. During this time the Auckland Transport Board refused to update the tramway network beyond what was absolutely necessary, considering significant upgrades to be a wasted investment. Consequently, by the mid-1950s Auckland’s tramcars were badly rundown. This caused some commuters to become hesitant to ride the trams, because they expected low-quality service and frequent breakdowns. These commuters promptly switched over to their motor vehicles instead, where most of them seemingly stayed even after trolleybuses took the trams’ places. Financial restraints prohibited instant replacement of the trams with trolleybuses, so the only alternative to the phase-in process would have been to retain and restore the trams after all. Had this happened, Aucklanders may have been less hesitant to ditch public transport, meaning the rate at which congestion in Auckland rose over the 1950s and 1960s might have been lower.

Finally, the shift from trams to trolleybuses potentially emboldened Aucklanders’ preferences for cars. For the private motorist, driving alongside trams was quite different to driving alongside trolleybuses. Tram tracks provided a less comfortable driving surface than the road, and when trams let passengers on or off, cars behind them were required to stop. In other words, trams made an assertive claim to the road. They owned it. Private motoring was rendered complicated and frustrating as a result.

Yet the shift to trolleybuses changed all of this. Kerb-side loading gave private motorists seamless travel without compulsory stops, and the removal of tracks provided smooth driving surfaces on all lanes. Although this was billed as a positive, it probably exacerbated congestion. In marked contrast to the trams’ assertiveness, Auckland’s trolleybus system deferred to cars, equipping private motorists with everything they needed to make their journeys more comfortable. Arguably, all this did was encourage more driving. Soon the trolleybuses had relegated themselves to the role played by Auckland’s public transport services ever since: the supporting cast to a domineering fleet of gas-guzzling, horn-honking cars.

This scene, on Newmarket’s Broadway, demonstrates how tram tracks shunted traffic to the side. Trolleybus installation freed up the centre of the road. (Photograph by unidentified photographer. Circa 1950. Reference: PAColl-6303-11. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23194172.)

Trams or trolleybuses – it didn’t matter

Yet the stronger argument is probably that congestion would still have risen (albeit at a slower rate) even if Auckland’s trams had been retained and restored, meaning that the switch to trolleybuses only had a small impact on increasing congestion overall.

The strongest point here is that the post-war explosion in private motoring was also driven by many other factors unrelated to the switch from trams to trolleybuses, despite our previous discussion. For example, Auckland’s increasingly sprawling geography forced commuters living in outer suburbs to purchase and drive cars, because cars were very flexible. Rising disposable incomes across the 1950s and the cut in wartime fuel rations in 1950 also made private motoring more accessible. Further, Aucklanders started to view private motoring as essential rather than as a luxury after World War Two. Therefore it often didn’t matter what form of public transport the Auckland Transport Board provided. In many instances, commuters liked their cars and would use them regardless of whether trams or trolleybuses were available as alternatives.

Of course, this car craze prompted many Aucklanders to abandon public transport. This, as we have already discussed, created road congestion. Yet that congestion also increased the running times of the Board’s trolleybuses, motor buses and remaining trams, making them less attractive to ride. Thus, even more people would turn away from public transport to their cars, causing congestion to rise even further, public transport running times to increase even more, and this vicious cycle to continue repeating itself. Congestion was thus driven by increased private motoring in both in the short-term and the long-term – all without the switch from trams to trolleybuses being particularly influential.

The Auckland Transport Board also found other culprits for the city’s congestion problems. The Board noted how 1950s shopping centres began emerging around suburbia, prompting Aucklanders to cease taking public transport to Queen Street department stores. Locals choosing to spend more money on goods rather than on public transport, the increasing popularity of television and a run of underwhelming summer weather were also cited by the Board as catalysts for falling public transport patronage across the 1950s and 1960s. All of these factors either prompted consumers to switch directly over to cars, or crippled the Board so much financially that services had to be reduced, which too drove disgruntled commuters to private motoring. Regardless of the path those factors took towards intensifying congestion, one thing was clear – they were not instigated by the switch from trams to trolleybuses.

Overall, then, the switch from trams to trolleybuses probably played only a limited role in fuelling Auckland’s congestion woes. The pull of the private motor vehicle over both forms of public transport – trams and trolleybuses – seems to have been the greatest catalyst for congestion’s development. Alongside this comes the fact that 1950s Auckland was a changing place. Many post-war developments in the city either hurt public transport services, encouraged private motoring or led to a combination of both.

The railway debate

It is actually really interesting to compare this to the railway debate. Did constructing motorways instead of a rail scheme contribute to Auckland’s congestion? Granted, the proposed rail scheme probably would have dealt with obstacles similar to those which plagued the trolleybuses and trams. Changing leisure and spending habits might have drawn Aucklanders away from the railway stations. So might have the rise of the private motor vehicle, convenient and increasingly affordable as it was. Nevertheless, it seems as though an improved railway system could have resisted the rise of private motoring admirably. The complete abandonment of the rail scheme for motorway construction probably did exacerbate Auckland’s congestion problems. How? Why? Let us examine our findings.

Railways alone would have failed

On one hand, of course the proposed rail scheme likely would have failed to reduce congestion very much on its own. We have already summarised this view in the previous article, and it has real merit. From the population living close to the existing and proposed railway stations, some definitely would not have taken the trains. Further, the rail scheme would not have changed the fact that Auckland’s railway lines failed to serve anywhere directly south of Epsom (except for Onehunga), so most people living in Mount Roskill and surrounding areas would probably have continued to drive to work. The North Shore had the same issue, as no rail lines were added to the Harbour Bridge.

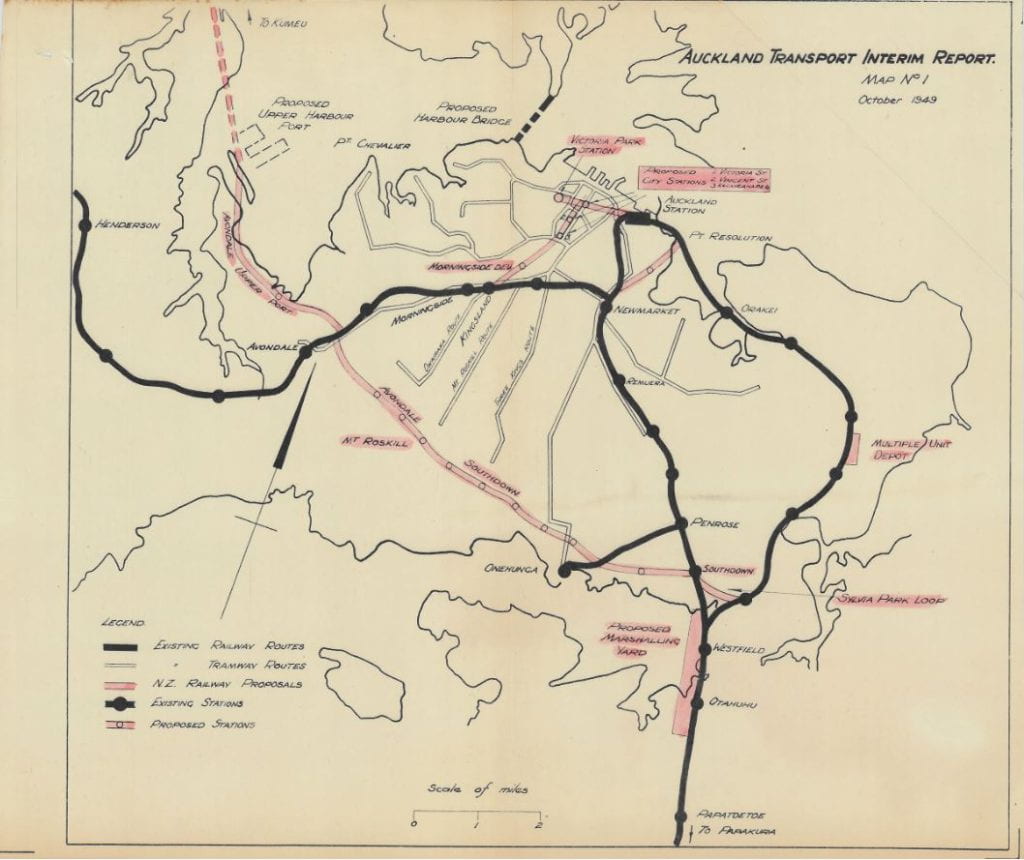

Scheme 1, as proposed by the Railways Department in 1949. Existing railway lines (black) did not stretch to the North Shore or Mount Roskill, and the proposed Morningside Deviation alone (centre, in red) would not change that. (Map No.1 from Halcrow and Thomas’ Interim Report on Auckland Transport, from Auckland Council Archives.)

With motorways, rail would have been invaluable

However, the rail scheme really could have helped to alleviate congestion if working in tandem with motorways. The motorway proposal clearly could not have been scrapped to make way for rail improvements. Road congestion was rising fast, and because motorways had a far wider catchment than the rail scheme, they would have provided a short-term, and therefore necessary, fix to congestion. Yet building the rail scheme as well – potentially by constructing fewer motorways initially to keep costs down – probably would have been the best solution. That way, rising private motoring could have been catered for instantaneously with increased road capacity, but many Aucklanders could also have been enticed away from their vehicles to trains, meaning that the growth of private motoring could have tapered off in the long run. Therefore, future pressure on the improved road system would have eased – not least because passenger trains are an incredibly effective mover of traffic, being unaffected by congestion, high-capacity, and far more efficient users of space than motorways. Of course, the Government had a budget in 1955. This precluded construction of both motorways and the rail scheme. Yet the power of hindsight suggests that more adventurous investment early on might have saved the city from the heady costs of congestion that it eventually had to pay. Sound familiar?

The problem with constructing motorways alone was that this funnelled more Aucklanders to their cars than ever before, actually exacerbating congestion in the long term. As railways were kept locked in their unappealing, inconvenient state, Aucklanders were left with just two options for their daily commutes. One was to drive. The other was to take road-based public transport: trolleybuses and motor buses.

Now, we did discuss in the last article how anti-rail activists expected motorways to reduce traffic on surface streets, and therefore encourage more Aucklanders to take the bus. In theory, this would alleviate road congestion in the long term. That never happened. In reality, many Aucklanders disliked buses regardless of how congested surface streets were, preferring their personal cars. Additionally, congestion on surface streets never actually disappeared. Auckland’s motorways were constructed slower than planned, meaning that total road capacity always lagged behind traffic and thus congestion was never properly thwarted. The motorways also contributed to traffic on surface roads themselves, by delivering masses of cars to them via motorway offramps. This rendered local buses less attractive than ever. Overall, constructing the motorways alone both scuppered railway improvements and annihilated the remaining appeal of existing bus services. Aucklanders were left with no choice: they had to drive everywhere. The motorways could not handle the unprecedented explosion in private motoring that followed, so by the 1970s and 1980s congestion was plaguing all city roads. Ironically enough, in trying to satisfy anticipated increases in private motoring alone, all the anti-rail activists did was make Auckland’s car obsession far worse. If an enticing alternative form of transport had existed, then Aucklanders may not have flocked to their cars as emphatically as they did over the following decades, meaning the city probably would have managed congestion better long-term.

But would Aucklanders actually have used rail? While some would not have, the view championed by anti-rail activists that practically all Aucklanders would reject an improved railway network in favour of their cars seems highly unlikely. Despite private motoring’s rising popularity, 1950s Aucklanders still used public transport in significant numbers. Across 1950-1951, the Auckland Transport Board carried 93 million passengers in a year. While many commuters switched from trams and trolleybuses to their cars over the next half-decade, even then more than half of all passenger journeys in Auckland in 1955 were made on some form of public transport. Notably, most public transport services available at the time were ageing rapidly or plagued by road congestion, so they weren’t particularly attractive either. Consequently, it seems possible – even likely – that many Aucklanders would have gravitated towards an appealing railway network if it were provided. The rail scheme would have fit the bill, offering modern, clean and high-capacity travel directly into the city, while also completely avoiding congestion, meaning that rail passengers could actually travel faster than cars on congested streets. As Halcrow and Thomas had suggested, then, why not give the rail proposal a try? If it had been successful, the benefits would have been huge. Suddenly, more and more cars would have been taken off the road, meaning rising congestion would likely have plateaued over the long term.

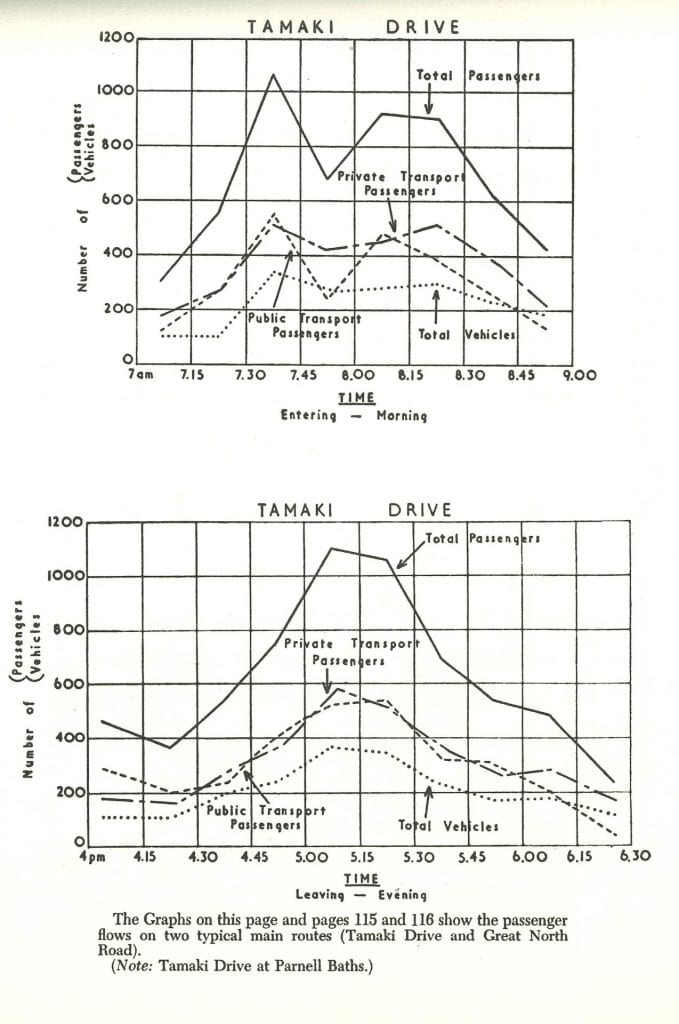

These graphs show passenger traffic on Tamaki Drive in the 1950s. Note how passengers were often evenly divided between private and public transport. The view that Aucklanders would soon not take public transport at all seems untenable based on statistics like these. (Master Transportation Plan for Metropolitan Auckland, 114. Image from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.)

Constructing suburban train station car parks, further, could have bolstered the rail scheme’s patronage even more. Suddenly, stations would have become accessible even if they were too far away to walk or bus to, meaning more Aucklanders could decide against driving their cars into the city centre. It is curious why anti-rail figures like Arthur Dickson, by contrast, championed city-centre car parks so much. These only gave Aucklanders more reason to drive to the city centre, which created congestion. Ironically (as an American anecdote), New York City’s experience might have been a better example to follow. The shortage of inner-city car parks there in the 1950s forced many commuters to use the subway or buses – an effective strategy to kick city travellers out of their vehicles.

Finally, although the proposed rail scheme failed to cover large swathes of Auckland, building it anyway could have kickstarted future railway expansion right across the city. Halcrow and Thomas had proposed future railway links to the North Shore and northwest, which both would have given many more Aucklanders the capability to travel by rail. This could truly have alleviated much of Auckland’s congestion in the long-term.

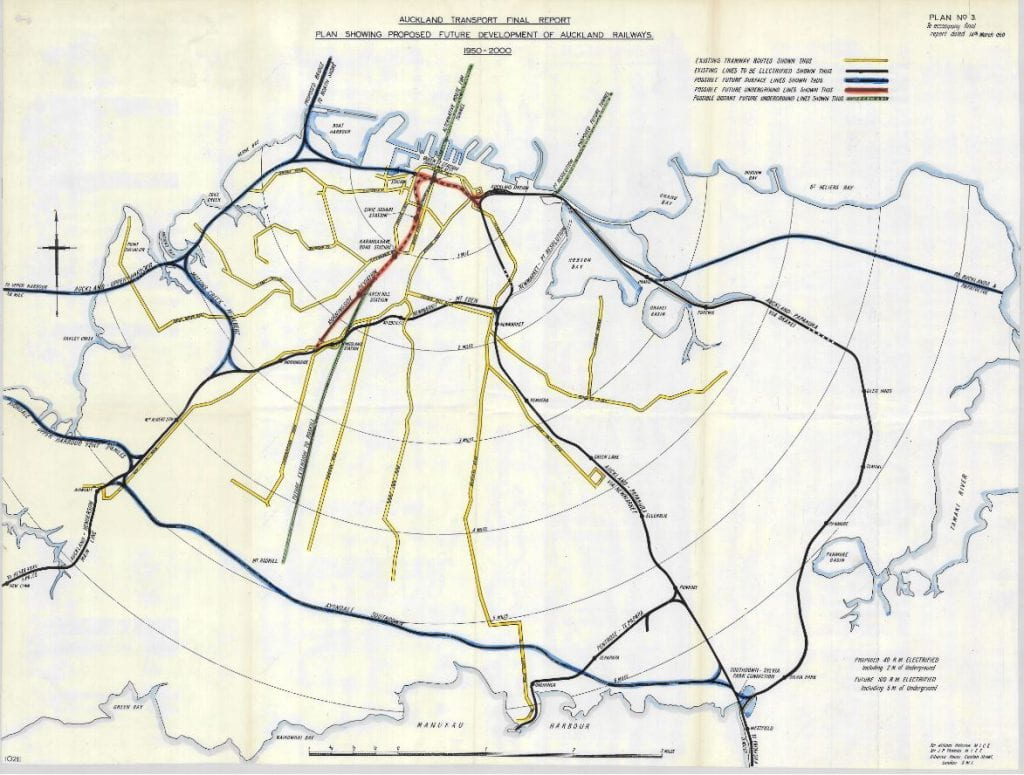

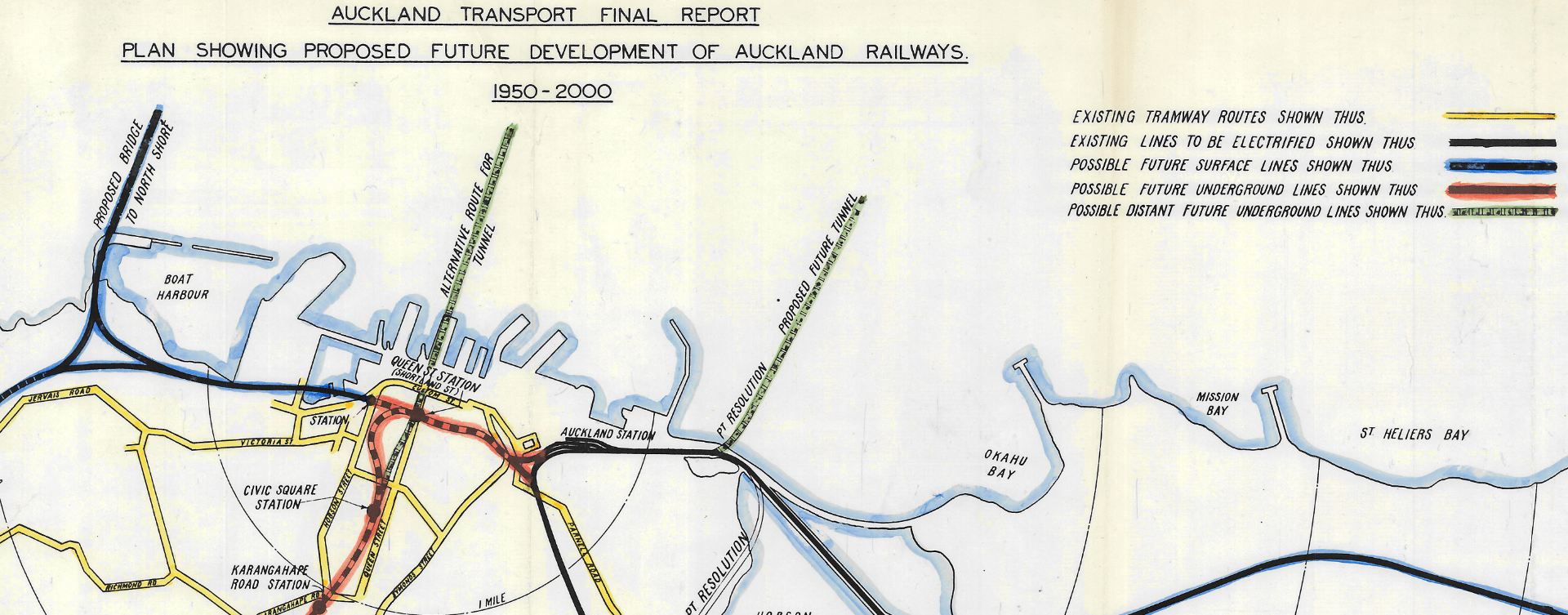

Halcrow and Thomas’ map indicating future plans for Auckland’s railway system. Note the Avondale-Southdown Link, and routes to the North Shore. (Plan No. 3 from Halcrow and Thomas’ Final Report on Auckland Transport, from Auckland Council Archives.)

A close-up view of Map No.3 as shown above.

Overall, the rail scheme would probably have failed to alleviate much congestion alone. However, only constructing motorways made road congestion worse in the long term because Aucklanders were given no viable alternative to driving. This caused private motoring to outstrip motorway capacity by the 1980s. What seems to have been required was a combination of road and rail – and thus, probably more expenditure than what the Government had originally budgeted for. This would have allowed Auckland’s roading system to develop and carry more cars, while also providing some Aucklanders with a functional, attractive alternative to driving that probably would have slowed long-term increases in private motoring. Ironically, exactly this kind of plan was tabled for Auckland across the late 1960s and early 1970s, once it became clear that motorways on their own would not solve congestion problems. However – as is a familiar story – this proposal eventually collapsed, bringing Auckland to its present-day predicament.

Conclusions

So, Auckland remains congested. People drive cars everywhere. How did we get to this problem? Might the city’s underdeveloped railways or non-existent trams have something to do with it?

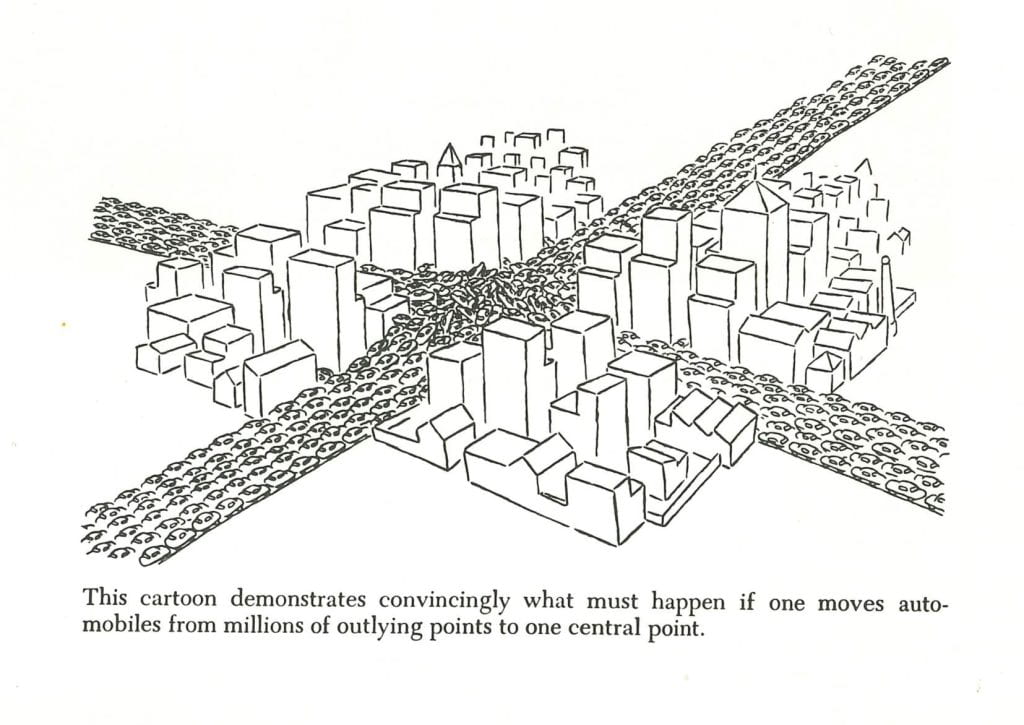

This 1969 cartoon predicted today’s problems quite accurately. (Cartoon from Dove-Myer Robinson’s Passenger Transport in Auckland: A report on overseas investigations of rapid-rail transport, 1969.)

It does seem that the switch from trams to trolleybuses in the 1950s had only a minor influence on growing congestion. Ultimately, Aucklanders preferred their cars to both forms of transport. Yet this is not to suggest that Light Rail, or something similar, will not work in the future. We live in a different age now. Compared to the 1950s, congestion is worse and cars are less exciting. The option to – and novelty of – taking a tram through Auckland could probably convince many contemporary commuters to ditch their cars.

Yet the abandonment of the rail scheme for motorways almost certainly drove congestion. When Auckland gambled its entire transportation future on private motoring in 1955, it forgot something crucial: transport systems carry people, not cars. As soon as a city caters exclusively to the latter, everything goes downhill. Only so many roads can be constructed on limited city land. Eventually, the onslaught of space-inefficient cars will fill them up. At that point, the sky darkens, the rain lashes down from the clouds, and the skulking threat of congestion begins to rear its head.