Part Four

How Auckland Ditched Rail for Roads and Rubber Tyres:

Motorway mania

Part One

The good old trams

Part Two

Trams out; trolleybuses in

Part Three

The tube

Part Five

Conclusions

by Sam Turner-O’Keeffe*

In the last article, we saw that Auckland had grown increasingly congested by the late 1940s, and that the city’s transport infrastructure was ill-equipped to deal with the projected further growth in private motoring. Facing an impending conundrum, the national Government viewed the development of Auckland’s existing railway system as a potential solution. In 1949 they commissioned Messrs. Halcrow and Thomas to analyse their plans for a new rail scheme. The engineers’ resulting report in 1950 endorsed a scheme involving electrification and the Morningside Deviation, and insisted on its hasty construction. Yet we know that neither electrification nor the Morningside Deviation ever materialised. Ironically enough, both projects are actually underway in Auckland currently, more than seventy years later. So, what happened? Why did the Government change its mind? Why was a roads-based solution to Auckland’s transport predicament eventually chosen over heavy rail?

Before we examine the events that took place after 1950, an important clarification needs to be made. We will see that local figures played a large role in Auckland’s eventual shift towards motorways. However, as might already be clear, it was the Government that had the final say over Auckland’s direction, because it owned and operated the city’s railways, and was the only entity capable of funding large-scale infrastructure projects. Thus, local figures were crucial only in the sense that they influenced the Government’s decision-making. Bodies like the Auckland City Council and Auckland Regional Planning Authority did not call the shots themselves.

Railways against motorways: the chronology

The period after 1950 began positively for the rail scheme. After receiving the Halcrow-Thomas report, the Government appointed a Committee of Enquiry to investigate the merits of its rail proposal in 1951. That Committee’s resulting report in 1952 made no serious objections to the railway plan. Accordingly, the Minister of Railways Stan Goosman officially confirmed in October 1952 that the Government would go ahead with both suburban rail electrification and the Morningside Deviation.

Stan Goosman in the 1960s. He would play an integral role in shaping Auckland’s transport future. (New Zealand Herald Glass Plate Collection, Auckland Libraries, 1370-262-23; photographer John Wilson.)

After this, the Government took some major steps toward starting construction. In late 1952, test drilling began near the Beach Road station, in preparation for the construction of a railway tunnel through to Shortland Street. Then in April 1953, the Government approached Halcrow & Partners – an engineering firm run by the aforementioned William Halcrow – to investigate the design and construction requirements for the Morningside Deviation. During the same month they also engaged Merz & McLellan, another engineering firm, to estimate the cost of the overall rail project. (This came to almost 11 million pounds, about twice what had been quoted in the Halcrow-Thomas report.) With all of this happening so quickly, it seemed certain that Auckland would have its electrified railway with an underground city loop. It was only a matter of time.

A year later, however, everything changed. In August 1954 the New Zealand Railways Commission – a body established by the Government to restructure New Zealand’s railways – submitted a memo to the Government. This recommended the cancellation of the rail scheme, because an authority capable of controlling all of the city’s public transport services was supposedly too difficult to be ‘readily established’. Without that authority, attracting enough passengers to make the rail scheme financially practicable would be unlikely, as bus, tram and trolleybus routes could not be co-ordinated to serve train stations. Minister Goosman agreed with this recommendation. Then in October 1954, the Auckland City Council voted to request the Auckland Regional Planning Authority (ARPA) to report on solutions for Auckland’s transport woes. Immediately, the Government suspended all work on the rail scheme and chose to wait for the ARPA’s report before proceeding further. That was crucial. Both the City Council and ARPA were dominated by anti-rail, pro-motorway activists, so any report created by the ARPA was certain to push for motorway construction over the rail scheme. Therefore, the Government’s choice to be advised by such a report simply revealed an intention to ditch rail. Thus, when the ARPA’s eventual Master Transportation Plan endorsed a road-based approach over rail, and the Government formally adopted it, this only confirmed the inevitable.

What convinced Goosman?

But what caused Goosman and the Government to switch from rail to roads like this? Finding a clear answer is difficult. A simple explanation could be that the Railways Commission’s memorandum convinced Goosman change his mind. Yet this is hard to believe. We know that the Auckland Transport Board already ran Auckland’s tram, trolleybus and (mostly) motor bus services in the mid-1950s. Extending that Board’s jurisdiction to cover Auckland’s railways and ferry services does not seem to have been particularly difficult. Additionally, by saying that the authority could not be ‘readily established’, the Commission might have meant that setting up that authority would be difficult to achieve immediately, but not in the longer term. If that is correct, a serious advocate of the rail scheme would probably not have revoked their support for it as quickly as Goosman did. Presumably they would have preferred to sacrifice short-term losses while the authority was still being created, in favour of long-term gains from the railway once the authority could be established.

It seems more likely that Goosman’s decision-making was influenced by many different factors, of which the Commission’s memorandum was only one. For instance, while opening the Southern Motorway in 1953 Goosman was quoted as having said: ‘my boy, the future of Auckland is with the motor car’. This suggests – albeit tenuously – that the Minister already preferred roading projects over rail schemes. Goosman himself also owned a road-haulage business: the construction of motorways was certainly familiar territory to him, and potentially financially lucrative.

Further, Goosman’s views were probably partly influenced by pro-motorway advocates on the ARPA and City Council. For example, in September 1954 the Auckland City Council established a special committee to investigate Auckland’s transport issues – this was the body which eventually recommended to the City Council that the ARPA draft their report. Included in this special committee’s ranks was Kenneth Cumberland, a leading pro-motorway advocate and ARPA member. From September to October 1954, the special committee met and conversed with Goosman: exposure to Cumberland’s pro-motorway stance may have fuelled the Minister’s growing anti-rail views. Similarly, on October 9 Goosman met with five other prominent decision-makers to discuss Auckland’s transportation future. One of those was City Engineer Arthur Dickson, another pro-motorway advocate and member of the ARPA. Predictably, Dickson pushed to scrap the rail scheme in that meeting, and endorsed motorway construction instead. This may have also resonated with Goosman; notes from that October 9 meeting suggest as much.

LEFT: Arthur Dickson, standing on the tractor and wearing business attire, circa 1940s. (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 464-10059.) RIGHT: Kenneth Cumberland, circa 1945. (University of Auckland Special Collections, Marjorie and Kenneth’s scrapbook, includes newspaper clippings, photographs and ephemera., 1938-1950s, MSS & Archives 2013/4, Series 12, File 12/3, Kenneth Cumberland papers.)

Of course, that was not the whole story. Auckland City Mayor John Luxford later portrayed Goosman as having instigated the Master Transportation Plan’s creation, by initially suggesting to Dickson that Auckland investigate constructing motorways instead of its rail scheme. This view was echoed by the New Zealand Herald, which speculated that the Government had actually pressured the City Council into requesting the ARPA’s report. Therefore, it seems unlikely that Goosman was actually forced into changing his mind by a mob of local anti-rail activists. Those activists’ constant pro-motorway rhetoric probably only emboldened the Minister’s pre-existing desire to abandon the rail scheme.

The logic behind anti-rail activism

Yet regardless of what convinced Goosman to prefer motorway construction eventually, the bigger question is this: why did anti-rail sentiment even exist? What was the logic behind it? This answer is not comprehensive, but rather a summary of the many arguments made by Dickson, Cumberland, Governmental figures, other anti-rail activists and – of course – the Master Transportation Plan. Given their breadth, these arguments will be split into three categories.

- Railways would not alleviate congestion

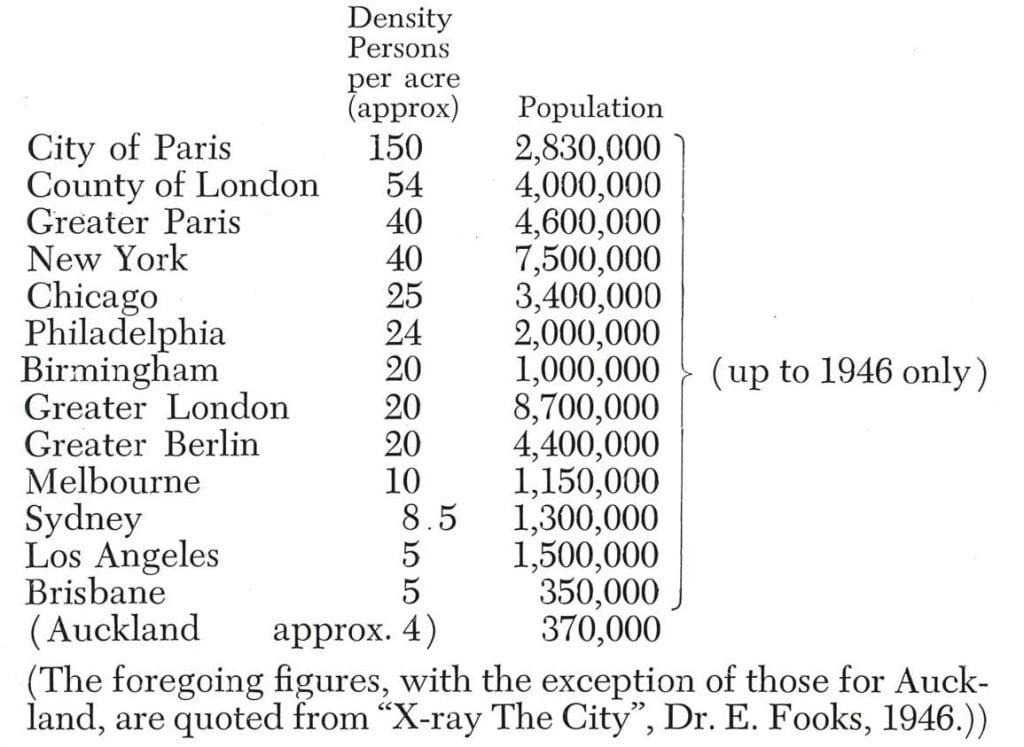

The logic underpinning Halcrow and Thomas’ rail scheme had been simple: to reduce road congestion, Auckland had to get people out of their vehicles and onto the trains. Yet anti-rail activists didn’t think that this would work. The first reason for this concerned Auckland’s population density. According to the Master Transportation Plan, in the mid-1950s Auckland’s population density was 4 people per acre – ridiculously low compared to foreign cities. This meant that by 1950 at least, only 44,000 people lived within a half-mile of all existing and proposed railway stations between Henderson and Papakura. That was about 12% of Auckland’s total population. However, this included not only the Morningside Deviation but also the Avondale-Southdown link, which was excluded from both the Halcrow-Thomas report and the Master Transportation Plan’s version of the rail scheme. Cutting out stations on that link left just 30,000 people within a half-mile of the remaining existing and proposed stations in 1950. Such low population density was not expected to change much, either, because Aucklanders were considered to prefer sprawling single-family housing to apartment living. Indeed, it was projected that by 1975, still only 14% of Auckland’s metropolitan population would live within a half-mile of the railways.

Auckland’s population density compared to that of foreign cities. These statistics fuelled anti-rail activists’ convictions that the rail scheme would fail in Auckland. (Master Transportation Plan for Metropolitan Auckland, 31. Image from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.)

To anti-rail activists, this would guarantee the failure of the rail scheme. Experiences in the Hutt District had indicated that only those living within a half-mile radius of train stations would walk to them; any further and people would bus to the station. Yet even with bus passengers included, it was forecast that a maximum of only 20% of Auckland’s population would be served by the updated railways. This did not necessarily mean that all these people would actually use the railways, either. For instance, Dickson noted that some people did not work in the city and thus would have little reason to take the train even if they lived close. Consequently, anti-rail activists were convinced that railway patronage would be extremely low. Even if the railways managed to carry 25 million passengers annually – Halcrow and Thomas’ estimated annual rail patronage, which anti-rail figures considered unlikely – the congestion relief provided was expected to be negligible.

With this in mind, it is curious why anti-rail activists disliked suburban train station car parks so much. Halcrow and Thomas had proposed the construction of these parks, saying that they would enable Aucklanders to leave their cars at nearby railway stations and take the train into the city. This would keep vehicles out of the city centre, and – crucially – enable commuters to reach train stations that would otherwise be inaccessible on foot or by bus. Yet anti-rail activists either completely ignored this proposition (as the Master Transportation Plan did) or at best unconvincingly dismissed it. For instance, Halcrow and Thomas had suggested that suburban car parks could take a minimum of 20% of Auckland’s private cars out of the city centre. Dickson responded by completely mischaracterising this projection, saying that car parks catering for a maximum of 20% of private cars would barely alleviate congestion, and therefore should not be built. Further, although Dickson acknowledged that commuters in New York and London parked at suburban rail stations before travelling by train into the city, he then stated that ‘conditions in Auckland are so different that the same practice would not be adopted’. Funnily enough, he failed to mention what those conditions were.

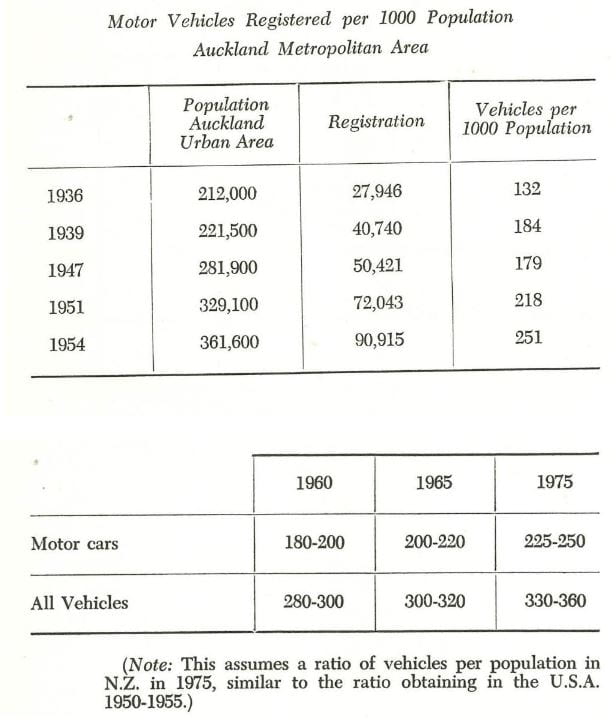

Alongside doubts about rail itself came the sweeping proclamation that Aucklanders liked their motor vehicles and would not stray from them even if the rail scheme were constructed. For example, Dickson estimated that even if the rail project transported 25 million passengers per annum by 1960, Aucklanders would still take 150 million passenger trips by motor vehicle in that year. This viewpoint was based on a number of factors. Cumberland argued that Aucklanders, being a wealthy bunch, preferred the flexibility, convenience and comfort of their personal motor vehicles over trains, even if travelling by train was cheaper. Dickson thought that some commuters would not tolerate having to stand on a train if its seats were all taken, and that others would dislike changeovers from feeder buses to trains on their daily commutes. He also felt that Aucklanders would be very quick to ditch public transport for their cars if they felt dissatisfied with its service. (This argument was probably influenced by the significant fall in patronage that Auckland’s rundown trams were experiencing at the time.) Anti-rail activists often referenced the United States, where cities with ‘fast, efficient and cheap’ railway services still had to construct highways to satisfy the demand for private motoring. In other cases, the simplest argument was used: Aucklanders owned a lot of cars, so they obviously liked driving and would not switch to the trains.

The rapid growth and projected growth of motor vehicles per 1000, as seen above, convinced anti-rail activists that Aucklanders would continue to purchase (and drive) vehicles even if the rail scheme were constructed. (Master Transportation Plan for Metropolitan Auckland, 90, 92. Images from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.)

Overall, then, anti-rail activists were deeply sceptical of the rail scheme’s ability to reduce congestion in Auckland. To them, an insufficient number of motorists would use the railways, due to either preference or geography. This was also accompanied by the reality that congestion in 1955 was far more worrying than it had been in 1949. Aucklanders owned almost twice the number of vehicles that they had in 1947, and with motorcar ownership rates, daily motorcar use and the city’s population all increasing more than post-war projections had anticipated, the situation was worsening. Therefore, the so-called ‘wait and see’ policy endorsed by Halcrow and Thomas – the policy to build rail first and wait before investing in roads – was expected to create an ‘intolerable situation’ in which congestion would explode unchecked because the railways would provide inadequate protection against it. In response the Master Transportation Plan proposed to construct rail later and in a reduced form, linking the Beach Road station to a new station at Victoria Street East. In reality, though, this spelled the end of the rail scheme. Replacing rail in first priority would be the construction of a network of motorways, as these were expected to deal with congestion properly.

2. Railways had other issues

Yet anti-rail figures also believed that rail would create other problems. The first of these concerned cost. Originally, Halcrow and Thomas had estimated that the entire Morningside Deviation would cost 5.5 million pounds, rising to 7.2 million if costs of electrification had to be included. However, as aforementioned, the overall cost had risen to almost 11 million pounds by 1954. At that price point the Government was starting to get cold feet. Granted, urban motorways would be more expensive than this – around 15 million pounds in total – but this was no issue because motorways were projected to deal with congestion very effectively, saving so much fuel and time that Auckland would actually profit on its investment. The rail scheme, by contrast, was expected to lose between 350,000-400,000 pounds per annum until 1980. As such, Cumberland dubbed the rail scheme a ‘white elephant’, as he thought it would waste money and provide few advantages.

Further, the railways were projected to influence Auckland’s development unfavourably. As mentioned earlier, Halcrow and Thomas had boasted that the rail scheme would fuel suburban growth. Yet anti-rail activists viewed this negatively. They argued that urban sprawl would use land inefficiently and also allow Aucklanders to leave the central city for residential areas further away, causing values of central city properties to drop. The expectation that the rail scheme would fail to alleviate city centre congestion was also anticipated to further fuel decentralisation, as workers would grow tired of slow central city commutes and resort to building alternative commercial areas in the suburbs. The result would be that Auckland’s central city would fall into decline, and that a ‘greater rate burden’ would be placed on all residential areas.

Lastly, there was disunity within rail supporters themselves. In 1954, the New Zealand Railway and Locomotive Society found several problems with the proposed rail scheme. The tunnelled route from Beach Road to Shortland Street would run straight through reclaimed land, creating construction and drainage issues. The Shortland Street station would also fuel more pedestrian congestion, and the scheme’s overall layout would make future connection with the North Shore difficult. However, the Society actually endorsed rail, bashing motorways and suggesting an alternative route through to Albert Park. Their views, then, were only minor in the overall opposition to the rail scheme.

3. The motorway network would alleviate congestion

Finally, anti-rail activists believed that a motorway network would provide an effective solution to growing congestion. The first reason for this, largely drawn from American anecdotes, was that motorways were better at transporting heavy traffic than ‘surface streets’, or normal roads. Their size meant that motorways could transport at least double the number of vehicles per hour. Motorists could also reach far higher speeds on motorways, and avoid the ‘stops and traffic interferences’ that plagued existing surface streets, meaning they could travel in free-flowing traffic. Anti-rail activists thought all this would reduce the number of accidents on the road and also slash commute times, reducing congestion considerably.

In a memorandum to Mayor Luxford, Arthur Dickson outlined how motorways were superior to surface streets. (Dickson, Arthur, “Railway Development Proposals and Provision for Local Passenger Transportation in the Auckland Metropolitan Area,” 20 October 1954, 7. Image from University of Auckland Special Collections.)

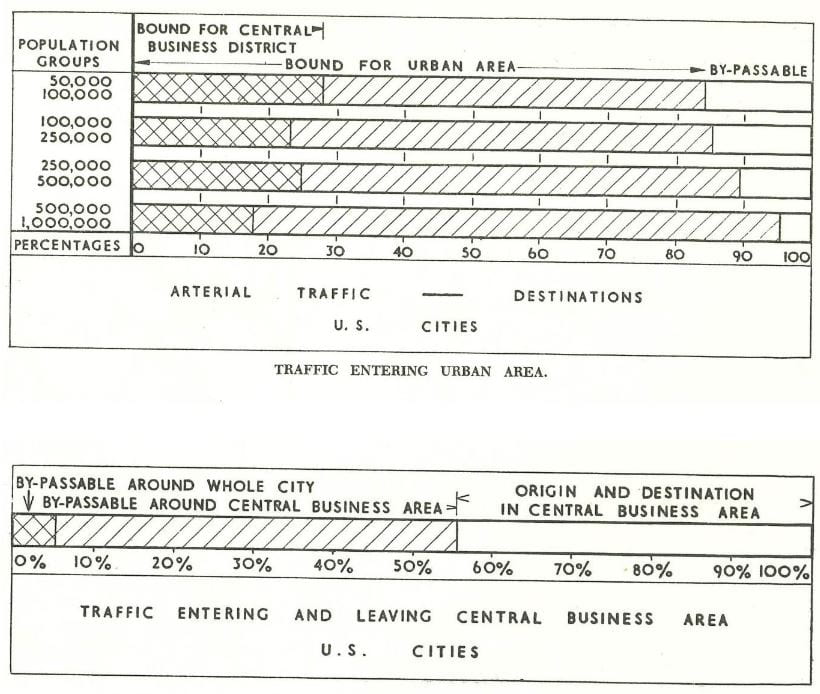

Further, anti-rail activists believed that their motorways would increase the number of routes available for motorists travelling to and from the outer city, alleviating CBD congestion. This argument relied heavily on American statistics. These indicated that most motorists approaching any American city from elsewhere intended to stop in the urban area, but not in the CBD. Likewise, about 55% of motorists travelling through American CBDs had not come from, or did not wish to end up at, the CBD. Without motorways, however, surface streets running through CBDs were often the only routes available for motorists to get to and from city outskirts, meaning they became congested anyway. By constructing motorways in an ‘inner loop’, bypassing the CBD but still serving the outer city, many motorists would be able to cease using CBD surface streets, affording them significant relief. This approach was to provide a basic guide for Auckland, both regarding its CBD and other built-up areas.

American statistics like these indicated that motorways bypassing Auckland’s CBD would solve the city’s congestion problems. (Master Transportation Plan for Metropolitan Auckland, 93. Images from Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.)

Lastly, anti-rail activists argued that motorways would ‘kill two birds with one stone’, by not only handling automobile traffic but also encouraging more people to use public transport. On one hand, as motorways would draw private motorists away from existing surface streets, buses and trams running on those streets would be faced with reduced congestion, meaning that they could reduce travel times and appeal more to the public. On the other hand, the Master Transportation Plan proposed to construct specially-designed bus stations along Auckland’s motorways, so that express buses could use the motorways to travel quickly, while occasionally pulling off onto bus-only areas in order to drop off and collect passengers. This would supposedly reduce congestion even further.

It is worth noting, of course, that many arguments favouring motorway construction could easily have been used – and perhaps more convincingly – to support the rail scheme. For instance, railways could transfer more passengers than motorways could per route mile, and could also have provided alternative routes across the city. Yet to anti-rail activists, this was immaterial, because railway patronage was expected to be embarrassingly low and therefore have no real effect on road congestion.

The outcome

Once the Government adopted the Master Transportation Plan, Auckland’s major infrastructure plan was set. Over the following decades, right up until the present day, a network of motorways was constructed across the city. Yet as we noted in the first article – and as you might already know from personal experience – Auckland remains congested even today. The pressing question, therefore, is whether the decision to supplant the rail scheme in favour of motorway construction had something to do with that. The final article will cover this, along with the effects of the switch from trams to trolleybuses.