Part Four

Marching: Aesthetics and Uniformity

by Katia Kennedy*

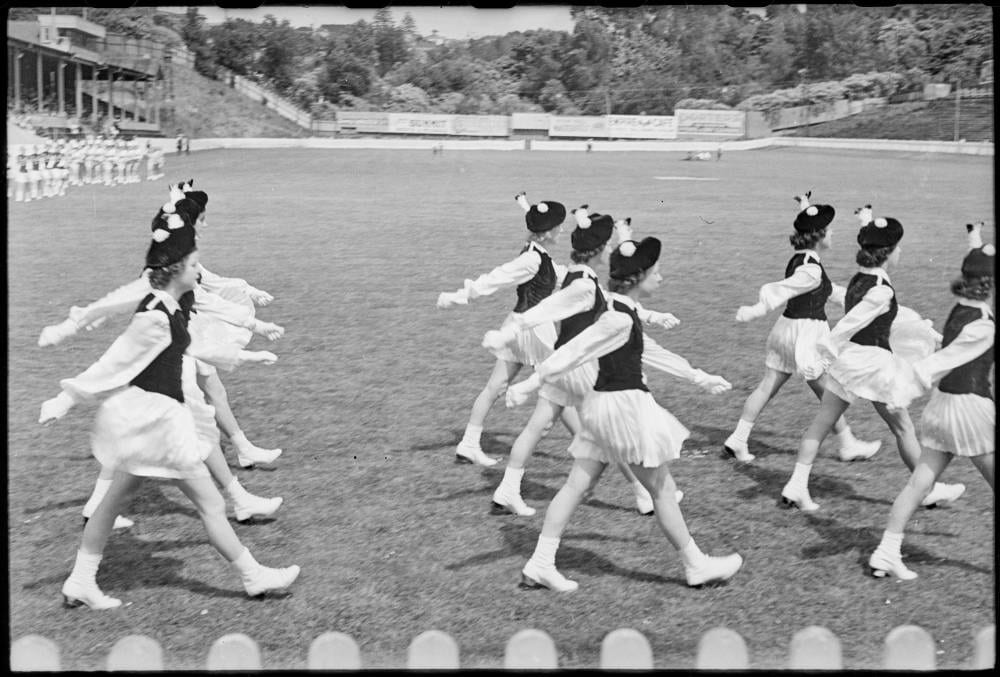

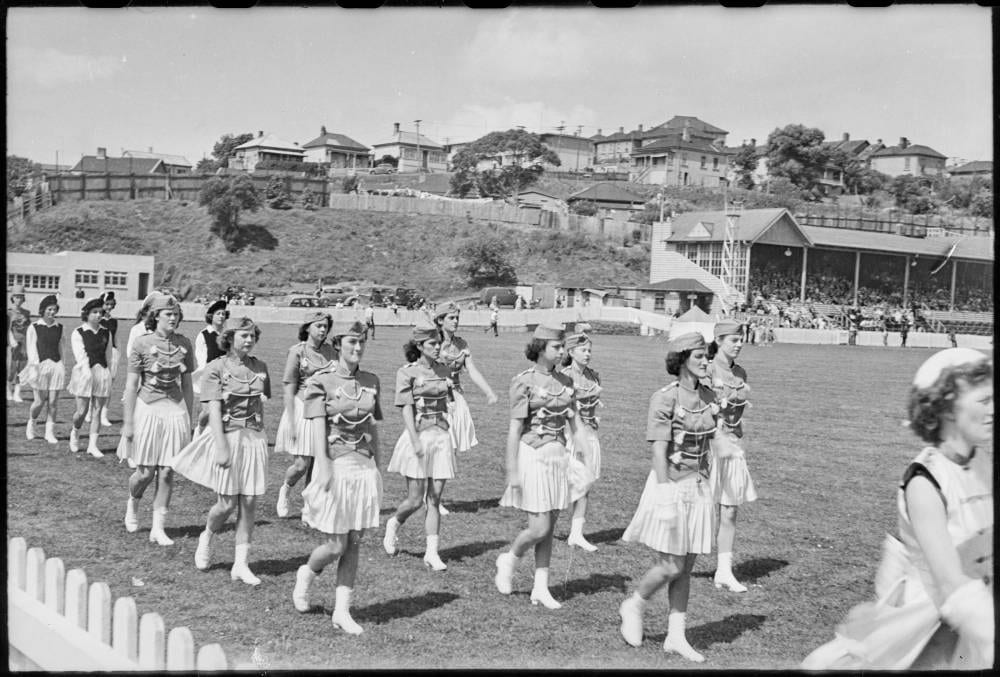

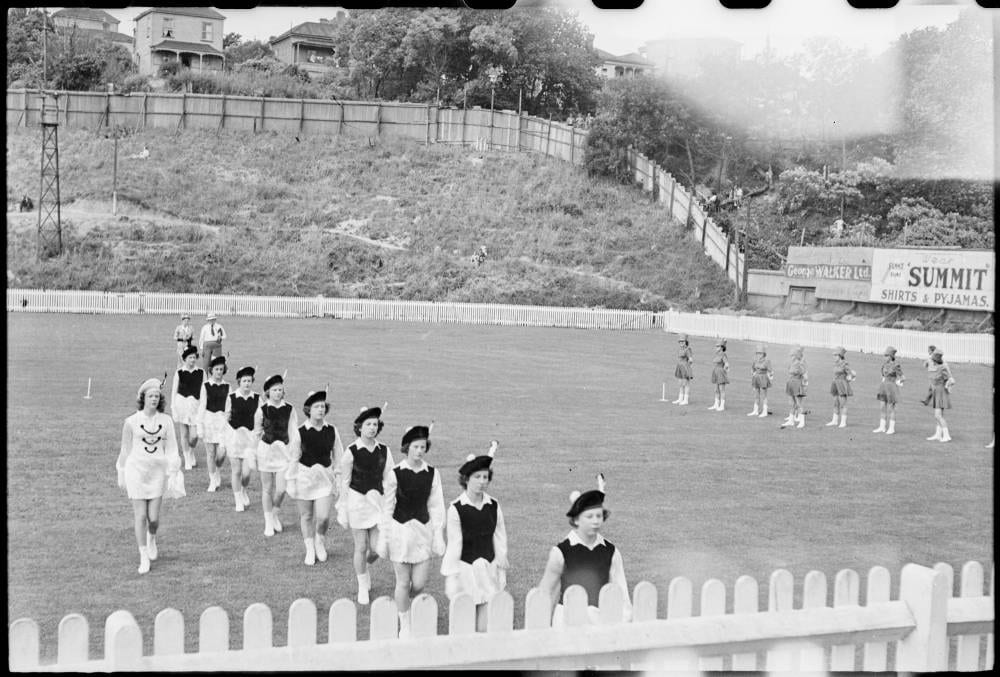

Figure 1: An unidentified marching team competing at Blandford Park. (Douglas Jerome March. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1959. Douglas March Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59421/rec/122)

Women’s marching was not only a very technical sport, but also a very aesthetically driven one. A marching team could achieve points for their execution of manoeuvres as well as for their uniforms. A marching girl’s uniform was an integral part of the sport and was assessed based on cleanliness, colours and general uniformity throughout the team.

Figure 2: Two judges at a marching competition. Graeme Letica (left) and Paul Phillips (Right.) Paul was also the Instructional Coordinator of the N.Z.M.A in the 1970s. (Unknown photographer. Marching Team Judges, Graeme Letica and Paul Phillips. 1980-1989. East Coast Bays https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/28801/rec/1 )

Along with technical judges, there was also a judge solely responsible for assessing uniforms known as the Costume Judge. Given the sport’s military background, it was very common for men to judge displays (although more women began to appear on the judging panel in later years).

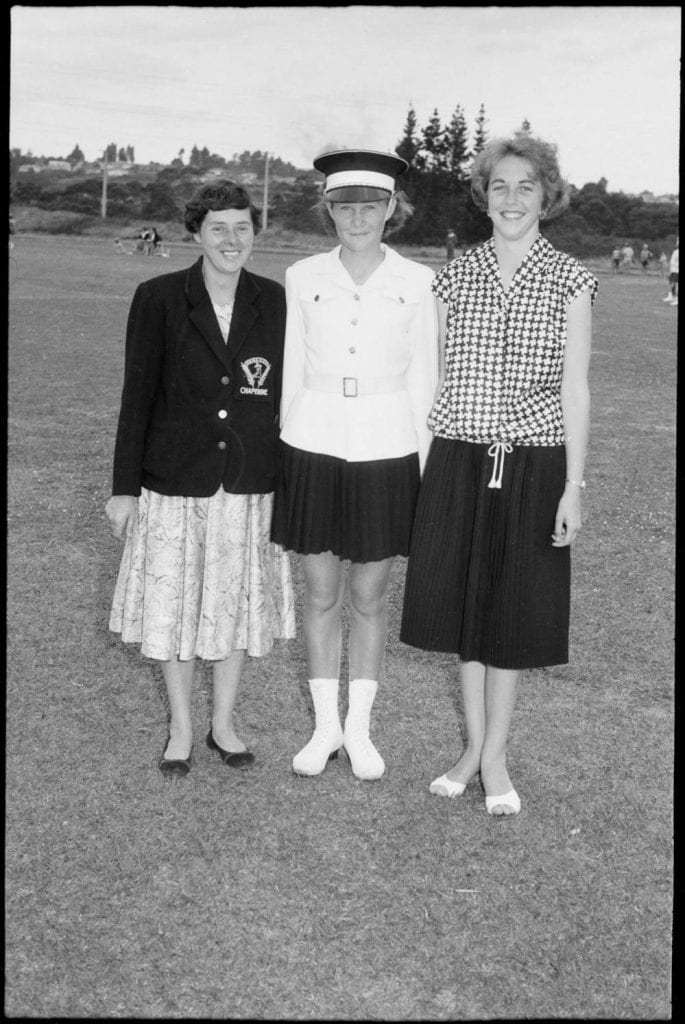

Figure 3: A full portrait of an unidentified marching girl standing at attention. She is wearing a hat, buttoned shirt with epaulettes, pleated skirt and white marching boots. (Rykenberg Photography. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/77051/rec/219)

This photo essay will showcase the wide variety of uniforms marching girls wore throughout the years. Despite the varying colours, patterns and designs, uniforms were expected to have the following: headwear, a jacket, coat, blouse, bodice or tunic, a skirt, underwear and footwear.

There is a wealth of marching photos available, indicating once again, the popularity this sport had in Auckland. However, almost every photo consists of primarily white women. This again raises the question of whether marching was deemed an acceptable sport because, in a similar sentiment to the 1880s, pakeha women were considered society’s ‘proper women.’

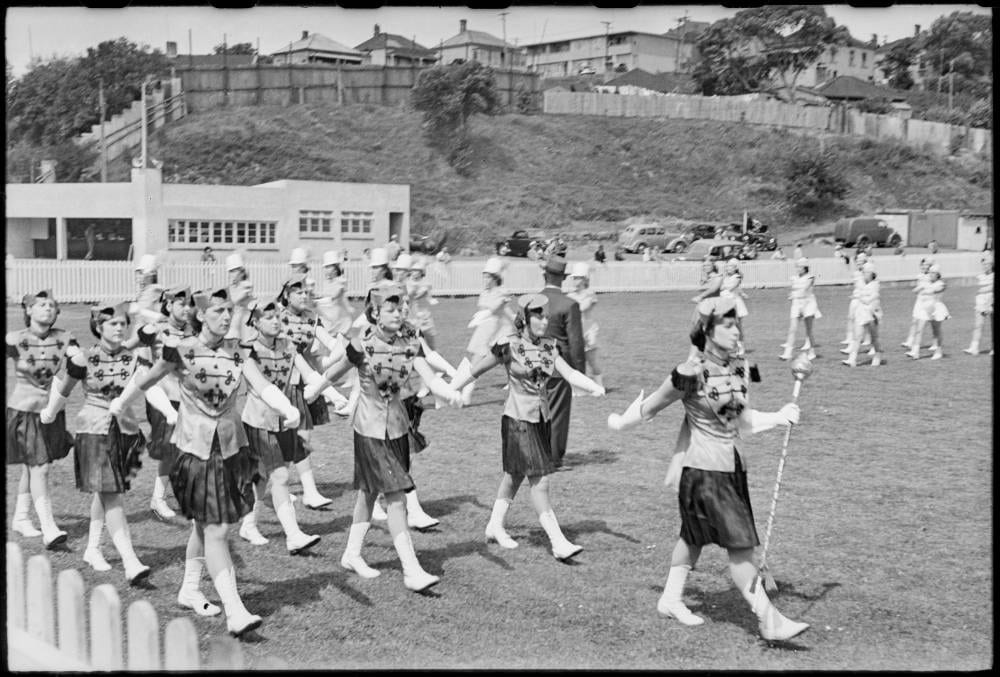

Figure 4: Group portrait of an unidentified marching team. Each girl is wearing a tunic and hat as their uniform. (Rykenberg Photography. Marching Girls Competition 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/71455/rec/96)

Figure 5: A team of marching girls competing at Blandford Park with purple and green uniforms. Behind, another team with yellow and blue/black uniforms can be seen competing. Both teams’ uniforms are made up of contrasting colours. (Douglas Jerome March. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1959. Douglas March Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59190/rec/48)

Uniforms were judged on a basis of attractiveness. Attractiveness did not pertain to the girl wearing the uniform, but rather whether the uniform itself was aesthetically pleasing. This included whether the uniforms complimented the event that the marching team was attending (bright coloured uniforms would likely not be worn if a team was taking part in a funeral procession, for example). Uniforms were expected to be made from “pleasing contrasting bright and gay colours, amplified and finished by suitable trimmings.” The colours needed to both contrast but not clash with each other. The many colour photos of marching teams and displays certainly demonstrate this.

Figure 6: Although this photo is of a team of marching girls in the Hastings Blossom Festival, it is a good example of the uniforms complimenting the nature of the event. (John Burgess Rowntree. Hastings Blossom Festival, 1965. 1965. J.B. Rowntree Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/89588/rec/16)

Figure 7: A team of marching girls competing at Blandford Park. (Douglas Jerome March. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1959. Douglas March Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59190/rec/48)

Figure 8: A team of marching girls (back left) performing in the Farmers Santa Parade with clowns. Their bright pink uniforms also compliment the nature of the Santa Parade. (Arthur E. Tinson. Famer’s Santa Parade, 1962. December, 1962. Tinson Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/89164/rec/295)

Figure 9: Team of marching girls at the corner of Quay Street East and Queen Street. (Douglas Jerome Marsh. Marching Girls in Quay Street. 1940-1959. Doug Marsh Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59513/rec/122)

Figure 10: The Leisure Lites women’s marching team performing during the Browns Bay Christmas Parade. Obviously the dress code for marching teams had lessened by the time this photograph was taken, but the brightness of the uniforms remains. (Pat Soar. Leisure Lites Women’s Marching Team, Browns Bay Christmas Parade. East Coast Bays Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/34326/rec/13)

There was quite a bit of freedom given to what could be included in the uniform, as long as every girl in the team wore it. Items like “shakos, busbies, helmets, etc.’ (see glossary) were suitable, as were capes, cloaks and plaid draped across the shoulder. Epaulettes, braids, cords, buttons, froggings and belts were also accepted. However it was not encouraged to mix-and-match items. Uniforms were expected to adhere to their chosen style and remain consistent in what paraphernalia accompanied it. The Judging Heading Interpretation by Paul J. Phillips states that:

“A formal military type of jacket requires a forage cap or formal headwear. Adaptations of naval uniforms require the appropriate headdress. Tartans and copies of Highland dress should be worn with the style of headwear usually associated with the Highland bands of Scotland. The bell-boy or drummer-boy type jacket requires a hat commonly referred to as a pillbox.”

Figure 11: The Kinloch marching team with their badges and trophies. They won seven Auckland championships by 1967 and were one of South Auckland’s most successful teams. Their headwear follows the Scottish/Gaelic inspiration of both the team name and uniform. (Murray Freer. Marching Girls, South Auckland, 1967. October, 1967. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/38409/rec/258)

Figure 12: The Papatoetoe Highlanders Marching Team. Like the Kinloch team and Scottish Hussars, their tartan skirts and headwear reflects their Scottish inspiration. (Ray Studio. Papatoetoe Highlanders Girls’ Marching Team, 1981. 1981. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/35583/rec/315)

Figure 13: An unidentified marching team competing at Blandford Park. Their uniform leans towards a military style and includes epaulettes and a forage cap. (Douglas Jerome Marsh. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1949. Doug Marsh Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59679/rec/88)

Figure 14: Three members of the Canadian Guards marching team outside the Auckland Town Hall. Their uniform includes a white coat, red pleated skirt and red busbies. (Donald Arrowsmith. Marching Girls Outside the Auckland Town Hall, 1963. February, 1963. Donald Arrowsmith Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/120957/rec/113)

Figure 15: An unidentified marching girl and her mother. (Rykenberg Photograph. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/79066/rec/2)

As meticulous as the process was to choose a uniform’s colours and appendages, it was just as important to retain a high standard of dress. Uniforms were marked, not just on attractiveness but also on cleanliness. For example, a marching girl’s uniform needed to fit snuggly. It could not “pull tight as the arms were swung” nor be too long or baggy. Such attention to detail extended to every part of the uniform, right down to the shoes and laces. Marching boots were most commonly white and both the shoes and the laces needed to remain so. This meant regular washing of the laces and whitening and varnishing parts the boots. Any grass stains, clippings or stray marks also needed to be removed. Most marching displays were held outdoors which would have resulted in frequent washing. This responsibility fell to the mothers. In fact, a mother’s involvement in the sport was made very clear before the formation of a team even began.

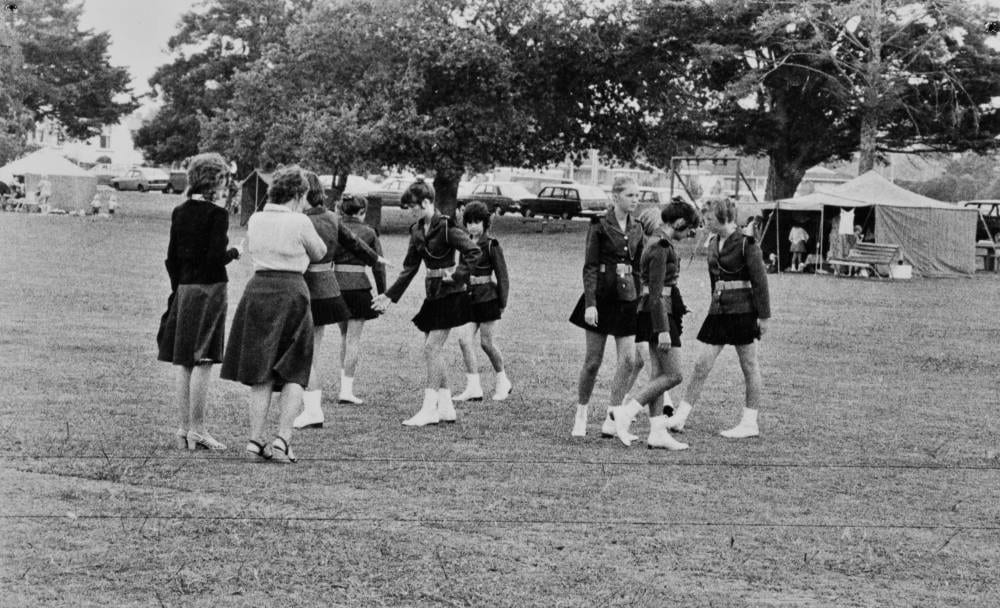

Figure 16: An unidentified East Coast Bays marching team practising before a display. Most Auckland competitions were held on grass in places like Carlaw and Blandford Park. It is easy to imagine how dirty uniforms would get and how difficult it would be to keep them clean. (Unknown photographer. East Coast Bays Marching Team Practising Before Competition. 1980-1989. East Coast Bays Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/30981)

Figure 17: Seventeen members of the Henderson Marching Girls team. The white boots each girl is wearing does not appear to change over the years – nor would the amount of cleaning needed to maintain their whiteness. (Frank Morris. Henderson Marching Girls Team. 1950-1959. Frank Morris Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/47433/rec/1)

Figure 18: A marching teams competition, held in a large park. (Unknown photographer. Auckland Girls Marching Teams on Parade, 1979. 1979. East Coast Bays Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/32576/rec/26)

Figure 19: Members of the Point England Swiftfoot Marching Team on parade in Fiji. The Swiftfoot marching team was one of the most documented Auckland teams to travel overseas. (Unknown photographer. Swiftfoot Marching Girls in Fiji, 1971. 1971. Mt Wellington Public Library Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/92474/rec/5)

When travelling overseas to compete, looking tidy was a must. If a girl was in her marching uniform, then her entire uniform, hat and gloves included, needed to be worn and her hair needed to remain neat and tied back. Smoking and drinking in uniform (and usually altogether) was prohibited, both for overseas travel and domestic displays.

Figure 20: The Point England Swiftfoot Marching Girls team in their travel uniforms with travel bags ready for their competition in Australia. The team would have been expected to maintain this standard of dress throughout their trip. (Unknown photographer. Swiftfoot Marching Girls, 1961. 1961. Mt Wellington Public Library Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/92293/rec/1)

Figure 21: An unidentified marching girl with her team’s chaperone and possible coach. (Rykenberg Photograph. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/79066/rec/2)

Ensuring the team’s cleanliness and uniforms remained up to standard as a whole fell to the Chaperone. Along with the Instructor and Manager, Chaperones were one of the adults in charge of a marching team. For marching teams, Chaperones were usually women (and Instructors usually men) who had “the girls respect and in return their welfare at heart.” The Chaperone had to be a woman of at least twenty years. They would become the “team mother” but were expected not to show bias towards any of the girls. Aside from being responsible for the upkeep of a team’s uniform, the Chaperone was expected to “ensure that the girls never act in a manner likely to bring discredit on themselves or the sport in general.” Like with the praised health benefits of marching, a Chaperone’s role in a marching team seems to have enforced the gender roles of the time. Nowadays, the Chaperone would likely have been absorbed into the role of a sports team’s manager, leaving only a manager and coach/instructor in charge of a team.

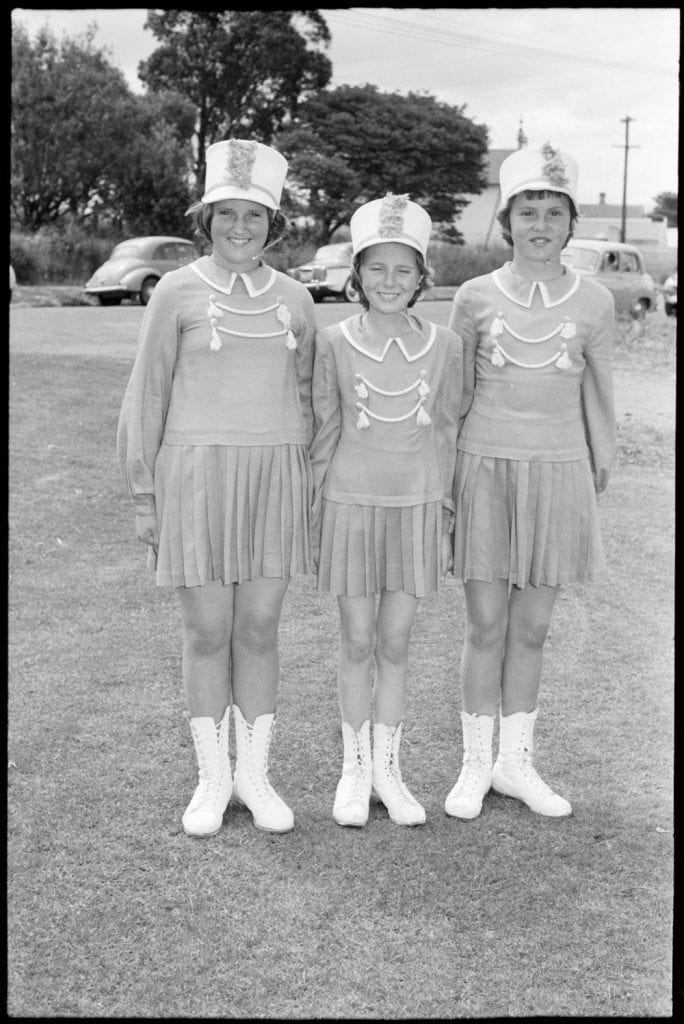

Aside from being judged for their execution of technical moves, another essential part of the judging process was the uniforms. This was undertaken by the Costume Judge. Uniformity was expected across the rest of the teams’ uniforms. Although there was allowed to be some disparity between the boots different girls on a team wore, the way each boot was laced needed to be uniform throughout the team. The laces were required form “bars across the boot or shoe” and insufficient lacing could incur penalties. Plackets and skirt fastenings had to be the same for every girl. Any ornamentation worn on the skirt or below the waist had be the same. For pleated skirts, there was no requirement for a uniform number of pleats but the width of the pleats was expected to be identical. Tartan skirts often posed an issue because pleating incorrectly could produce a different colour/pattern than the rest of the team. The expected uniformity extended to the girls’ undergarments as well. Any underwear that became visible during a display would be judged along with the rest of the uniform. The garment would be subject to be assessed on the basis of “fit, cleanliness, neatness, etc.”In order to achieve this, teams would often by underwear in bulk (or “laces panties” in this case) and distribute them to team members along with the uniforms.

Figure 22: A group photo of an unidentified marching team. In these group portraits, it is easy to see the uniformity most teams tried to (and often did) achieve. (Rykenberg Photography. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/81801/rec/209)

Figure 23: The Musketeers East Tamaki Marching Team pictured with their Instructor and Chaperone. (Belwood Studios. The ‘Musketeers’, East Tamaki, 1964. 5 August, 1964. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/35637/rec/6 )

Figure 24: Three unidentified marching girls at a competition. Although it is difficult to see, each girls’ boots are laced identically. (Rykenberg Photography. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/79120/rec/90)

Figure 25: The Papatoetoe Highlanders’ Marching Team pictured with their Instructors, Manager, Chaperone and awards. The attention to detail/uniformity of their tartan skirts is more obvious in a group photo. (Unknown Photographer. ‘Junior Champions’, Papatoetoe, 1964. July, 1964. Footprints Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/36678/rec/20)

The uniformity extended outside of the uniforms to the girls themselves. Instructors and judges preferred the girls to look as identical as possible. This involved wearing “leg paint” to ensure the girls’ skin colour was uniform across the team. Self-tanning lotion was also frequently advertised in the Quick March magazine. Paul Duval’s “instant tan” was advertised to achieve the “uniform smartness of a “team tan” every time [a team faces] the judges.” The need for uniformity extended so far that some instructors preferred their girls to be the same height and size. Naturally, this was likely seen as quite problematic and was perhaps one of the reasons why marching disappeared from the public eye.

In order to deal with the different heights and sizes of girls in marching teams, a technique called “sizing” was recommended. This was a military method that placed the tallest girls on the outside and the shortest in the centre. Sizing made the teams appear tidier and helped to disguise any issues in the march plan that different leg lengths may bring. The photos of marching teams during displays usually makes it difficult to tell whether the girls are different height because of this.

Figure 26: An unidentified team of marching girls arranged in height order. Even standing in height order, a majority of the girls are similar heights and attention is drawn to the uniformity of the team rather than the height differences. (Rykenberg photography. Marching Girls Competition, 1959. 1959. Rykenberg Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/79152/rec/91)

Figure 27: A group portrait of the Point England Swiftfoot Marching Girls team standing in height order. (Unknown photographer. Swiftfoot Marching Girls, 1950s. 1957. Mt Wellington Public Library Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/92507)

Figure 28: An unidentified marching team competing at Blandford Park. From this angle and the use of sizing, the girls in the team all appear to be the same height. (Douglas Jerome Marsh. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1949. Doug Marsh Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59136/rec/20)

Figure 29: An unidentified team of marching girls competing at Blandford Park. Once again, thanks to the angle of the photograph and the use of sizing, the girls appear to be identical. (Douglas Jerome Marsh. Marching Girls at Blandford Park. 1940-1949. Doug Marsh Collection. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/59634/rec/35)

Women’s marching was a very aesthetically driven sport. Not only were the marching girls’ uniforms judged as part of a point system, but uniformity was expected across the team, almost to an extreme level. The drive for perfection and obsession with how young girls looked and were perceived in this sport’s culture perhaps played a large role in its decline during the 1980s. As we have seen, marching and women’s cricket had drastic differences in their developments. My final article will explore how these differences contributed to where each sport is today.

Glossary:

Trimmings: materials that are directly attached to clothing and can have functional and aesthetic purposes. E.g., buttons, braids, zippers etc.

Shako: tall, cylindrical military headwear that usually has a visor. A shako often includes a feather, plume of pom pom attached to the top.

Busby: the English name for a cylindrical fur cap, originally Hungarian.

Forage cap: a coloured, peaked cap word by the British Army.

Epaulettes: an ornamental shoulder decoration usually used to denote rank.

Froggings: decorative looped fasteners, usually found on a military uniform

Pillbox hat: a women’s hat with no brim, straight sides and a flat top.

Bell-Boy/ drummer-boy jacket: fitted, double-breasted jacket often with braids or piping, commonly worn by drummers boys and hotel-bell boys. The style is based on 19th Century military dress uniforms.

Bibliography

Bowen and Phillips, Come Marching… An Introduction to the Sport of Marching. The New Zealand Marching Association: New Zealand. The New Zealand Marching Association, Box 3, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

Inder, Pam. “From an Instructor’s Viewpoint.” unpublished, circa 1950-1959. The New Zealand Marching Association Records, Box 1, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

Lloyd, John H., Doug F. Macdonald and S. Ruth Haswell. The New Zealand Marching Association (Inc.): Introduction to Midget (Non-Competitive) Marching. New Zealand: The New Zealand Marching Association (Inc.), 1979. The New Zealand Marching Association Records, Box 2, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

The New Zealand Marching Association (Inc.), A Brief History 1945-1977. The New Zealand Marching Association: New Zealand. 1977. The New Zealand Marching Association, Box 2, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

The New Zealand Marching Association, “Forming a New Team 10 Months in Advance.” unpublished, 1976. Box 2, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

The New Zealand Marching Association, “A Mother Looks at Marching,” Quick March 1, no. 56 (1956): 1. Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

“New Zealand Marching Association (Inc.) Technical Bulletin.” Unpublished 1958-59. The New Zealand Marching Association Records, Box 1, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

The New Zealand Marching Association, “Step Out this Season with a Perfect Tan,” Quick March 1, no. 125 (1961). Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

Phillips, P.J. “Brief Note as a Guide to the Essence of Each Heading.” unpublished, circa 1950-1959. New Zealand Marching Association Records, Box 1, Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

RNZ. “Marching Girls New Zealand Society.” Accessed February 14 2023. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/nz-society/20140321