Part Three

The Borders of Identity: Illusions in Auckland’s Chinese History

by Hanna Lu*

Let’s start with an end. ‘Chinatown’, located in what is now the city centre’s Greys Avenue, faded out of existence in the 1960s. As its buildings were demolished and its residents moved out, the 1966 Auckland Star published an article in which the author mourned that “Chinatown has gone—and with it one of the more colourful links with Auckland’s past”.[1]

Popular accounts like these conjure images of paper lanterns and a bustling street full of Chinese people and Chinese languages, and as this hub fell, it seems, its people assimilated into Auckland proper.

The Chinese children growing up in this new context spoke English and were second, third and fourth generation New Zealanders. They “mixed with Europeans in schools and homes”, had adopted the “Kiwi lifestyle”, and thought “the same way as the European”.[2] These Chinese residents were now accepted “as equals”, declared the 1957 Auckland Star, and so “there was great hope for that universal fellowship which right-thinking people so earnestly desired” — fellowship that demanded blindness to the “disquieting difference, that yellow skin”.[3] The authors of these articles did not mean to be derogatory. In fact, they write almost in celebration: Congratulations! You are one of us now. Come be part of this arbitrary grouping, we’ll forget that you are Chinese, you and I both.

This project draws on a selection of fourteen interviews conducted by the Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation, with descendants of people who paid the Chinese-only poll tax implemented in 1881. They talk about their lives and those of their families. In them there is a discernible thread of loss: Ella Hoy Fong, for example, never celebrated Chinese New Year as “hardly anyone did”, and many learned Cantonese but forgot it because of lack of use.[4]

What the interviews also tell us, however, is that Chinatown was far from what the newspapers made it out to be. Chinese people did live there, but they were attracted to it because of its proximity to the Auckland markets, the availability of housing, and its cheap rent — not because of zoning.[5] And it was only a few shops. Other, non-Chinese patrons, business owners, and tenants came in and out as well.

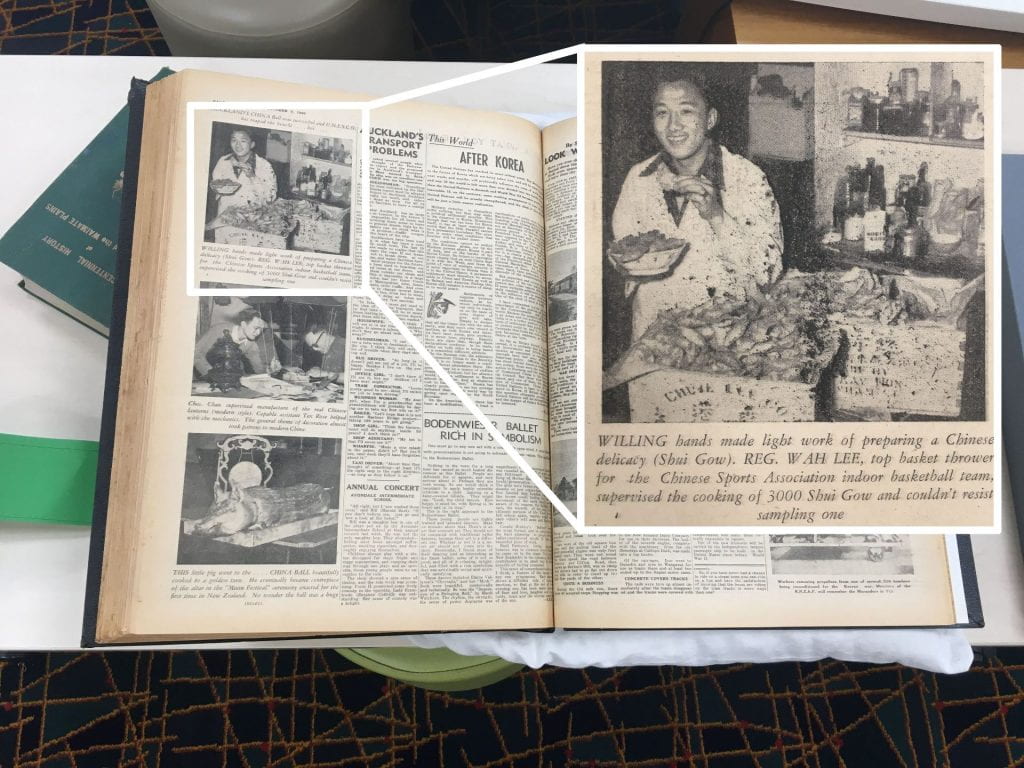

Those who did stay there didn’t see Greys Ave as a Chinese-only space. Barry Wah-Lee, who lived above the family business at number forty-five, would invite Chinese passers-by in for tea and make friends with the Samoan men spending time there while their wives and children were at church.[6] There is a sense of responsibility over his establishment, to host and make people feel welcome, but no implication that those of other ethnicities are intruding. Permeability is the norm.

Barry: There was a teapot and a basket, which I used to offer to visitors, with some cups sitting in a big crockery thing with water, you’d tip it out, probably rinse it. … If I see Chinese out on the street Dad would always say hello.

Sue: How many people would take up the offer for a cup of tea?

Barry: Oh I think most people, most people would, yeah.

Barry: That’s where we met the community. Actually, it’s interesting, some of the Samoan people used to come, used to spend a lot of time at our place. I think their wives and children would be at the church. It was good for me because at Christmas and New Year there’d be really good sing-songs. … Some of the Samoan people were well-known bruisers outside, but I think because some were terribly disrespectful to them, you know, calling them whatever they call them, in pubs and that. But at our place they treated Dad very well, they were very nice to you. You wouldn’t want to call someone ‘coconut’ and get away with it. … Maybe they came for the vermicelli, the vermicelli that we’ve got the tape recorder sitting on. And then Kevin Ryan would have some of his first business, cause he would help them out if they got into trouble.[7]

Most interviewees in this group were never in Chinatown in the first place: Ella Hoy Fong lived in Mangere, Mavis Lowe in Onehunga and then Parnell, May Sai-Louie in Newmarket, and Joana F. Sang and David Wong in Remuera.[8] Visitors, friends and new immigrants came to these homes all over Auckland to eat and stay, and the hosts themselves travelled to school and work nearby or in the city.

This dispersion did not mean that they were no longer Chinese. Also, cultural loss was not a one-way street. May Sai-Louie went to China, stayed for four years and returned fluent.[9] Barry Wah-Lee’s father taught himself written Chinese.[10] Many others sent their children to weekend classes at the Chinese school set up by Reverend Chau in 1930, while Mavis, as a grandmother, “hopped up” to the Manukau Institute of Technology to learn Mandarin and graduated with her daughter-in-law.[11] They watched movies on projectors, first silent, then sound, in English at the theatre and in Chinese at the State Theatre.[12]

Ella: He did a lot of exporting for the Chinese, and he used to pick out the films and send them back to New Zealand.

David: And so you’d get the movies down, and you advertise, and you have a screening, whereabouts were the pictures shown?

Ella: On Symonds St.

David: was that a Chinese Hall then?

Ella: Yeah, it was a Chinese Hall then. Every weekend, they used to take films, Chinese films. Different ones every weekend. And I think they had a lot of younger Chinese there, learning the Cantonese language, to read and write.[13]

Willie: Auckland City was really buzzing, in those days. The footpaths and that would be full of, especially night time, jam-packed. … We used to go dancing every Friday night. Betty used to come with us! I used to learn dancing at Margaret O’Connors, around the back of Queen St. … You could learn the waltz, foxtrot, slow foxtrot, the rhumba and all that, tango.[14]

Other activities don’t quite come under any umbrella: music at the Town Hall, fishing at the wharf, providing fireworks for the Queen’s visit in 1953, racing.[15] David’s parents played mah jong every Sunday lunchtime before going home to sleep ahead of the market on Monday.[16] They listened to radio in the evenings, went to mix n’mingle nights, watched games at Eden park, and held sold-out balls at the Peter Pan on Queen St to which socialites, businesspeople and politicians like Rob Muldoon were invited. Proceeds were donated to charity.[17]

This is a sense of identity that is harder to capture. What does it mean to belong to a group? At what point can we say that someone is no longer a Chinese person, and that they meet a nebulous set of criteria to qualify as a New Zealander?

Variety in culture and leisure were not the only ways in which the interviewees defied ethnic stereotypes. We know that Chinese people worked in three main industries — as market gardeners, fruiterers and laundry-people — but that is also transient. Willie and Elsie Wong ran their shop for 40-odd years. The children benefited from the shop as they grew up, but their Auckland offered them more opportunities that didn’t necessarily align with the solutions of their parents’ world. With no-one to be passed onto, the business closed.[18]

Bordered ethnic areas are especially interesting as an issue because of the two later attempts to create Chinatowns in Auckland. The first was in the late 1980s. A New Zealand Herald article from the 10th of January, 1989 describes plans for a “Chinatown and Oriental Market” along Britomart Place and Quay Street, “busy and exotic” — but half of the discussion is taken up by branding: “We’ve spent two years promoting the idea of a Chinatown to our shareholders, investors and developers. We will do what we have to in order to protect the name.”[19] Their plans, we can see, did not quite take off as they had hoped.

The Chinatown and Oriental Markets: Judy Cheung, Robert Ottignon and Muoi Ly, in Wong, Gilbert. “Race on for the REAL Chinatown.” New Zealand Herald, January 10, 1989.

The second attempt to create one on Dominion Road, in 2011, attracted more widespread condemnation — “Chinatown misses point: You can’t fake history”, writes Brian Rudman.[20] It all reeks of artificiality.

There is no need for enclaves for any of Auckland residents to know who they are. Ethnic clusters can be sites of cultural vibrance, but that can be true outside — if ‘outside’ is not hostile to it. Deep diversity, even if we don’t state it explicitly, is something that we already recognise and practice.

*Hanna was one of four students awarded a 2020 Summer Scholarship out of a highly competitive field. Her project focused on a group of Chinese families in Auckland in the twentieth century and she describes this topic as a timely one. As we grapple with the urgent need for ethnic diversity in history, this research highlights moments of grace in Auckland’s past, and suggests a reorientation in the way we write about ethnicity and what Auckland has been to its people.

[1] “Chinatown is Gone…” Auckland Star, October 26, 1966.

[2] “Change in Auckland’s Chinatown.” The Weekly News, January 26, 1955; “Chinese now adapting to life in N.Z.” Auckland Star, October 25, 1957.

[3] “Chinese now adapting to life in N.Z.” Auckland Star, October 25, 1957; Bickleen Fong, The Chinese in New Zealand: a study in assimilation (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1959), 9-10.

[4] Ella Hoy Fong (née Wong), interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, July 2, 2009, audio; Wah Ying Chau (Chong), interview by Charles Chan, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 4th Project, July 21, 2015, audio; Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, August 20, 2009, and September 6, 2009, audio.

[5] Lily Lee and Ruth Lam, Sons of the Soil: Chinese Market Gardeners in NZ (Dominion Federation of New Zealand Chinese Commercial Growers, 2012), 315-7.

[6] Barry Wah-Lee, interview by Sue Gee, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, June 4, 2006, audio.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ella Hoy Fong, interview, Mavis Lowe (née Ah Chee), interview by David Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, July 15, 2010, audio; May Sai-Louie, interview by David Wong and Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 1st Project: 21 Voices, October 23, 2007, audio; Joana F Sang (née Wong Hop), interview by Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, January 19, 2012, audio.

[9] May Sai-Louie, interview.

[10] Barry Wah-Lee, interview.

[11] Wah Ying Chau, interview; Mavis Lowe, interview; Ella Hoy Fong, interview.

[12] Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview; Joyce Khoo and Cheryl Num, interview by Charles Chan, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 4th Project, September 27, 2014, audio.

[13] Ella Hoy Fong, interview.

[14] Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview.

[15] Barry Wah-Lee, interview; Thomas Wong Doo III, interview by Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, September 1, 2011, audio; Wong-Yee Chan, interview by David Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, July 21, 2011, audio.

[16] David V Wong Hop, interview by Edwin Welch, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, August 22, 2011, audio.

[17] Wah Ying Chau, interview; May Sai-Louie, interview; Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview; Thomas Wong Doo III, interview by Lorna Wong, Chinese New Zealand Oral History Foundation 2nd Project, September 1, 2011, audio.

[18] Willie Wong and Elsie Wong, interview; David Wong, email correspondence with author, April 10, 2020.

[19] Wong, Gilbert. “Race on for the REAL Chinatown.” New Zealand Herald, January 10, 1989.

[20] Rudman, Brian. “Chinatown idea misses point: You can’t fake history.” New Zealand Herald, June 24, 2011.