Part Four

Qianjin! – Capital, COVID-19 and Chinese Students

by Laura Prahash*

冒着敌人的炮火, 前进

Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn!

Braving the enemies’ fire, march on![1]

This time last year, there were discussions on whether to let Chinese international students back into New Zealand, given the spread of COVID-19. With each discussion of letting the students back in, emphasis was placed on how much these students were worth to our economy. One broadcast in March 2020 mentioned that the educational sector was still hopeful that the ban on Chinese students returning would be relaxed, as “the international education market is worth around $4.8 billion dollars, and Chinese students make up about a third of the yearly intake.”[2] COVID-19 highlighted just how much economic value we place on international students, especially Chinese students, but when did we begin to see them this way?

The international student community in Auckland started out as a cultural body in the 1950s, transitioning to a political force in the 1970s. At the end of the 1970s, the New Zealand Government decided to increase the fees paid by private international students, with full-fees being charged starting in 1989. The former education-as-aid model that drew the first students from overseas to our shores was now squarely portrayed as education-as-trade. Using the case study of Chinese international students in Auckland during the 1990s and early 2000s, we will see how the international student community shifted to being viewed as an economic commodity to be enticed, acquired, and retained, and we will consider how COVID-19 affected this.

Let’s Talk Numbers

There were very few Chinese international students in New Zealand prior to 1999, as New Zealand restricted the number of incoming Chinese students following the Tiananmen incident. The quota was relaxed in late 1998; the following year, China also implemented an act that caused the international education market to boom.[3] After New Zealand was endorsed by China as “an acceptable educational destination”, the number of international students in Auckland soared.[4]

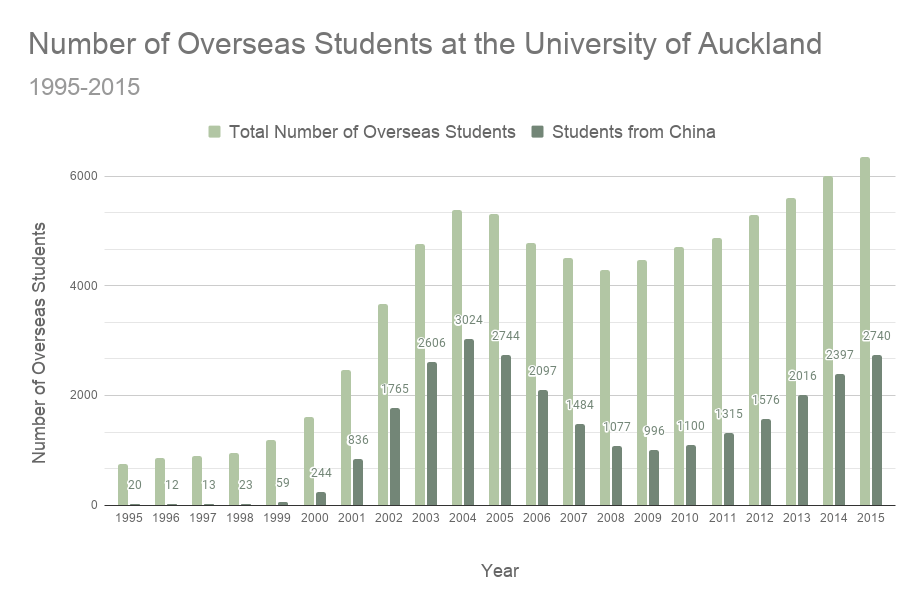

When several Chinese students were asked why they chose to study in New Zealand as opposed to elsewhere, their response included that it was cheaper, had a lower English language requirement, and that they had wanted to study in the UK or US but could not due to visa or financial issues. Some students also opted to study in New Zealand and use this opportunity as a stepping stone to get to their original goal of the US or UK.[5] Regardless, there was a huge boom of Chinese students at the University of Auckland within the next three years, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The number of overseas students at the University of Auckland between 1995 and 2015[6]

Setting the Scene

Prior to the big boom in student numbers, there was already an undercurrent of anti-Asian sentiment in Auckland. This corresponded with the surge in Asian migration to Auckland in the early 1990s.

The 1987 Immigration Act made immigration to New Zealand far more accessible for people outside of Europe and the UK. As a result, large numbers of Asians came in subsequent years, with the majority settling in Auckland. The increased number of Asian immigrants led to the popular media expressing racist sentiments which the public bought into. For example, an inflammatory article titled “Inv-Asian” was printed in all Auckland suburban newspapers in April 1993.[7] This article was met with a response of unprecedented strength from the Chinese community within Auckland and nationwide, and put the often-ignored issue of anti-Asian racism into the spotlight.[8]

Manying Ip, a lecturer at the University of Auckland and spokesperson for the Chinese community, noted how this racism had also made its way onto campus and that there was such a large number of incidents reported that an anti-racial-harassment week was being planned at the University.[9] The most popular joke on campus was:

“How do you know when an Asian has broken into your flat? Answer: Your dog has been eaten but your homework has been done.”[10]

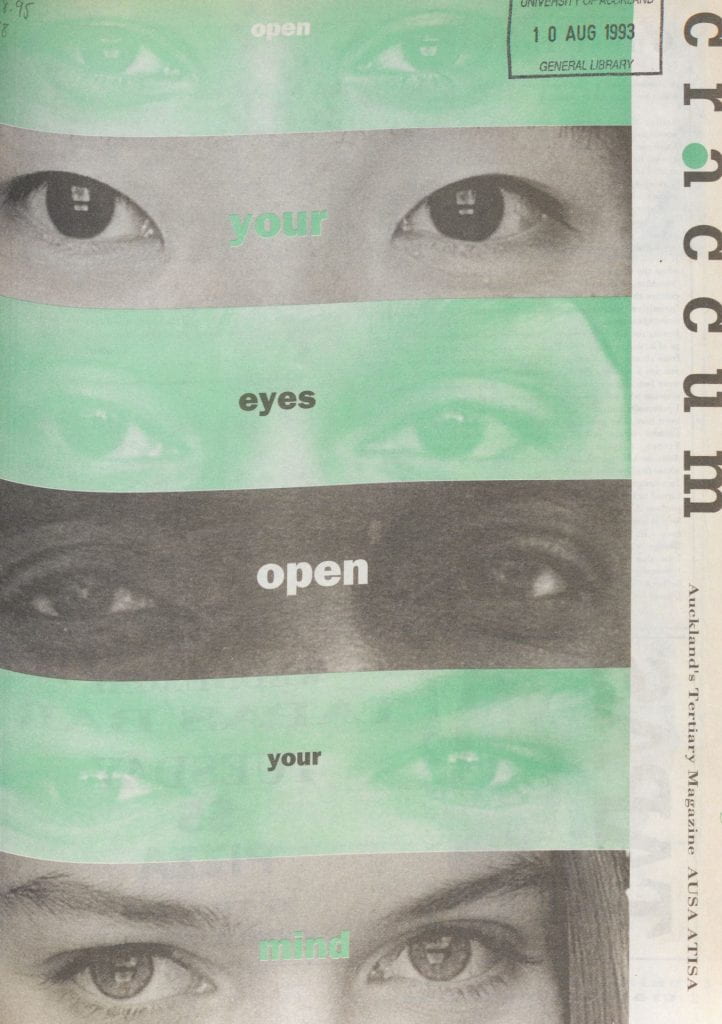

Cover of Craccum Volume 67, Issue 19 (1993). This issue contained an article responding to “Inv-Asian”.[11]

This anti-Asian sentiment was expressed on campus in other ways. Desks in the library were covered in racist graffiti, and “Asian bashing team names” at a campus pub quiz were met with “rapturous applause”.[12] Students on campus who were interviewed noticed the ill-feeling between Asians and Pākehā, with several commenting that it likely stemmed from economic issues.[13]

This only worsened in the early 2000s, as the numbers of Chinese international students soared, resulting in increased visibility on campus and in the CBD. Letters published in Craccum, the University of Auckland’s student magazine, although not reflective of the whole student population, provide examples of the strong racial prejudice felt by members of the student community. Several students echoed a sentiment expressed earlier by politician Winston Peters, comparing walking down Queen Street to being in “the heart of Beijing” or a “scene from a China town movie…disgusting!!!”.[14] Another lists steps that could be taken to “prevent this country being colonised for a second time”, which included voting for Peters, getting a gun license, purchasing a firearm and joining a guerrilla group.[15] Many letters, although less vitriolic, made fun of their English or complained about their pervasive presence on campus, with almost all criticising the lack of integration or assimilation.

But the international students responded. One acknowledged that although some Asian students “make trouble here”, those were the minority.[16] They also emphasised how much money international students brought into the economy. Auckland saw these students as a valuable economic commodity and the students were aware of this too.

Another student wrote saying that he came for the lifestyle and because he wanted “to be a kiwi”. However, because of what was happening, he was planning to go to Australia the following year.[17] One student, who had been in New Zealand for close to a decade and felt truly integrated, challenged those who complained about the lack of integration, asking them how often they had been the one to initiate an interaction or relationship with the international students.[18]

These examples of international students countering the letters published in Craccum not only showed that they were engaged with campus politics and the wider student body, but that they were also standing up for themselves, aware of how they were perceived and trying to challenge current attitudes and misconceptions.

Shaping Auckland

The influx of Chinese international students shaped our housing market, particularly in the CBD and inner suburbs. The rent for inner-city apartments rose by 20 percent within nine months in 2002.[19] But as the number of international students in the CBD soared, quadrupling in just three years, the number of weekend shoppers also declined, shifting the balance between commercial, educational, and residential sectors in the heart of our city.[20]

Some communities in Auckland were resentful of what they saw as the “Asianisation of streets and suburbs”.[21] An editorial in the Herald reminded those angry at how visible the Asian community now was in Auckland to bite their tongue because those very students contributed $1.7 billion to our economy in 2002, and that if treated badly, the students (and therefore their economic value) would go elsewhere.[22] It is again a reminder that the presence of these ‘foreigners’ was only being tolerated due to the temporary nature of their stay and the huge amount of income they poured into the economy.

Whether they were welcomed or merely tolerated, the Chinese international students caused the education sector to grow in leaps and bounds. By 2003, education was the fourth largest industry in our country.[23] But the boom in international student numbers from China would soon come to a halt.

Boom And Bust

In 2003, two prominent private language schools in New Zealand closed due to bankruptcy, leaving thousands of Chinese students stranded.[24] The recent SARS outbreak affected those living in New Zealand on foreign currency due to unfavourable exchange rates. There were also several instances of Chinese students being targets of crime, and even murdered. A case of extortion or kidnapping was being reported at least once a week, and there were likely dozens more unreported.[25] All of these factors were picked up and publicized by the Chinese media, and the Ministry of Education in China warned private students about the potential dangers of studying in New Zealand.[26] As a result, the number of incoming Chinese students declined rapidly, with new visa applications almost halving in 2003 (See Figure 1).[27] Action was taken by the New Zealand government to bring these numbers back up again, such as promising increased protection for international students, meeting with Chinese officials, and attending Asia-targeted conferences.[28]

Then and Now

The number of Chinese students in Auckland and around the country has increased since 2003, but a stereotype has developed alongside the numbers. There are countless memes about international students where the punchline is that they have wealth and spend it on luxury goods and fashion.

Two images that make fun of the international student stereotype[29]

They are seen as gamblers who spend money like water,[30] bad drivers who own luxury cars,[31] ‘filthy’ smokers and spitters[32]. These are all characteristics of the stereotypical international student, a stereotype that is itself racialised, associated with Chinese students. The Chinese media has a term for this stereotype: “study abroad garbage” (留学垃圾, liúxué lājī[33]). This perception of Chinese students is not limited to Auckland; rather, it is part of a global phenomenon.[34] The students are our “golden burden”—they’re valuable, but bring with them a host of problems, with students in Auckland reportedly struggling more than in other parts of the country.[35]

Despite Auckland being the “hub of international education in New Zealand”, international students there felt that locals were more unfriendly towards them. These students were also far less likely to recommend New Zealand as a study destination compared to students from elsewhere in the country.[36] Chinese students in particular appeared to be far more dissatisfied than students from other countries.

When interviewed by a Chinese journalist, the Chinese students spoke out about several issues: feeling “a sense of unspoken loneliness”, locals not appreciating Chinese culture and being unhappy when the students spoke Chinese, that there was a lack of common interests and integration was difficult. One student said that the only way they felt they could fit into New Zealand society was through forfeiting their own culture.[37]

The international students were derided by local students because they did not meet their expectations of integration or assimilation; in less formal terms, that they didn’t make an attempt to hang out with the locals.[38] The Chinese students largely attribute this to three things: the language barrier, and a difference in cultural expectations, and that when they do try to push past these, they are often treated with condescension. Auckland’s urban environment and high density of international students explains why many international students have fewer local friends and a weaker grasp on English compared to elsewhere in the country, because the lack of support and interaction between locals and internationals makes it easier to just stick with the people and things that are already familiar. As Auckland locals, if we make an attempt to bridge the gap, then we can help to address issues of alienation and loneliness. In time we can ensure that international students in Auckland are just as satisfied as those elsewhere in the country.

The Influence of COVID-19

The Government announced just weeks ago that they are letting a thousand international students back into the country, starting with those that ‘bring the highest value’, but also increasing the living expenses requirement for their visa by 33%, to $20,000.[39] Once again, it appears that economic concerns are at the forefront of the University’s treatment of international students, even when they’re not yet on our shores.

Responses to COVID-19 around the world raised issues about how governments prioritise the economy over the health and well-being of people. As a group of people whose time here is intimately linked to the economy, international students experienced this twice over, especially Chinese international students who had to bear the brunt of racism due to the association of COVID-19 with China.

COVID-19’s impact on international students has turned the spotlight back on the dynamic relationship Auckland City has always had with these transient residents. We need to make sure that we don’t lose our humanity while looking out for our economy. Each student is an individual with their own goals, desires, and fears, more than a cultural representative or economic resource. These students have come to Auckland to experience a new way of life, to have independence and freedom, and to gain a qualification. They are at the mercy of their home and host governments, institutions, and host communities.

From cultural ambassadors, to a political force, then an economic commodity, our perception of the international student community has undergone many shifts over the past 70 years. Despite the challenges that international students may face or bring to our society—issues of crime, loneliness, or language barriers—we are desperate to keep holding on to this “golden burden”. Their presence is an opportunity for far-reaching exchange and expansion, both personally and as a nation.

I know this all too well. I am an Asian migrant who came over as a permanent resident with a skilled parent. But my ability to do so, as part of a cultural and skills exchange, is the eventual results of decades of policy and culture shift around international students. To end with a quote from former Prime Minister Helen Clark, “through international students we get to see the world from a different perspective,” an opportunity we should not take for granted.[40] I, for one, am grateful.

[1]This is from the People’s Republic of China’s national anthem – 义勇军进行曲 (March of the Volunteers). I thought it was appropriate because as you’ll read later in the article, the Chinese students kept on “marching on” despite the “enemy fire” of racism and stereotyping. Lyrics and translation taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/March_of_the_Volunteers.

[2]Q+A. Series 2020, Episode 3. Aired 1 March 2020, on TVNZ 1; University of Auckland TV and Radio Service, accessed 25 January 2021. https://www.library.auckland.ac.nz/tv-radio/title/VA_27631_05.

[3]Phoebe H. Li, ‘New Chinese Immigrants and Contemporary New Zealand Chinese Media’, in A Virtual Chinatown: The Diasporic Mediasphere of Chinese Migrants in New Zealand, Chinese Overseas, Boston, Brill, 2013, 69.

[4]The Export Education Industry: Challenges for New Zealand. Asia:NZ, 2003, 10.

[5]Colleen Ward, and Anne-Marie Masgoret, The Experiences of International Students in New Zealand, Wellington: Ministry of Education, 2004, 13-14.

[6]University of Auckland Annual Report. Auckland, N.Z: University of Auckland. Statistics taken from the reports from 1998 to 2015.

[7]‘The Inv-Asian’, Auckland City Harbour News, 16 April 1993. This is just one of many newspapers that this article was published in.

[8]‘Rare Asian Complaint’, New Zealand Herald, 10 May 1993.

[9]‘Chinese make their presence felt’, New Zealand Herald, 24 February 1994.

[10]‘Chinese make their presence felt’.

[11]Craccum, 67, no. 19 (1993).

[12]Craccum, 66, no. 8 (1992); Craccum, no. 23 (2003).

[13]‘RACE’, Craccum, 66, no. 18 (1992), 30-1.

[14]Craccum, no. 10 (2003); Craccum, no. 12 (2003).

[15]Craccum, no. 12 (2003).

[16]Craccum, no. 13 (2003).

[17]Craccum, no. 16 (2003), 34.

[18]Craccum, no. 23 (2003), 36.

[19]‘Billion-dollar student boom’, Sunday Star Times, 19 May 2002.

[20]‘Auckland’s Changing Face: Restoring Queen St’s Allure’, New Zealand Herald, 23 December 2003.

[21]‘A bob each way on overseas students’, Dominion Post, 15 August 2003.

[22]‘We are losers if foreign students leave’, New Zealand Herald, 28 August 2003.

[23]‘We are losers if foreign students leave’.

[24]New Zealand pledges to better protect international students’, China Daily, Accessed 15 January 2021, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/en/doc/2003-12/05/content_287791.htm.

[25]‘Kidnapping cases hit one a week’, New Zealand Herald, 10 May 2003.

[26]Li, ‘New Chinese Immigrants and Contemporary New Zealand Chinese Media’, 69.

[27]‘Loss of Chinese students to hurt NZ education industry’, China Embassy, Accessed 15 January 2021, ://www.chinaembassy.org.nz/eng/xw/t58256.htm.

[28]‘New Zealand pledges to better protect international students’; ‘Education team to target China’, New Zealand Herald, 28 August 2003; ‘Foreign Minister Winston Peters is trying to woo more Chinese students to NZ”, Prime News at 5:30, 15 November 2005, Accessed 25 January 2021, https://www.library.auckland.ac.nz/tv-radio/title/VA_10577_04.

[29]Asian Cvndy (@_Chapati_Head_), ‘International students breakfast.’ Twitter, 18 October 2018, 11:26am. Accessed via Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/groups/ucsdmeme/permalink/559999257798785,; Miren Lagerda, “nobody: international students:”, Facebook, 5 November 2019, https://www.facebook.com/groups/1343933772408499/permalink/2146425378825997

[30]China Youth Daily, ‘Xinxilan zhongguo xiao liuxuesheng shengcun baogao 新西兰中国小留学生生存报告’ [Survival Report of Chinese Elementary School Students in New Zealand], last modified 27 March 2004, http://zqb.cyol.com/content/2004-03/27/content_845145.htm. (accessed 28 January 2021).

[31]‘A bob each way on overseas students’, Dominion Post, 15 August 2003.

[32]Craccum, no. 7 (1998), 8.

[33]‘Survival Report of Chinese Elementary School Students in New Zealand’.

[34]‘Naxie chumujingxin de “liuxue lese” shei lai “qingsao” 那些触目惊心的“留学垃圾”谁来“清扫”’ [Who will ‘clean up’ those shocking ‘study abroad garbage’?], last modified 28 April 2005, http://math0.bnu.edu.cn/~lizh/others/liuxue.htm, (accessed 28 January 2021).

[35]China Overseas Chinese Network 中国侨网, ‘Mudu xinxilan zhongguo liuxuesheng zhi guai xianzhuang 目睹新西兰中国留学生之怪现状’ [Witness the strange situation of Chinese students studying in New Zealand], last modified 16 November 2005, http://www.chinaqw.com/news/2005/1116/68/5814.shtml (accessed 28 January 2021).

[36]C. Ward, A. Masgoret, ‘The Experiences of International Students in New Zealand’, Ministry of Education, Wellington, 2004, 47, 62.

[37]Bai, Limin 白莉民, Chu guo liu xue yu yu xiang bu dao de wen ti : Xinxilan Zhongguo liu xue sheng sheng cun bao gao 出国留学与预想不到的问题 : 新西兰中国留学生生存报告 [Meeting the challenges: Chinese students’ experience in New Zealand], Shanghai: Hua dong shi fan da xue chu ban she, 2008, 124, 126-7, 132. Translation provided by my mother.

It’s worth noting that because this journalist is from China, the students may have felt more free to talk about their issues as compared to talking to a New Zealand journalist, and communication would have been much easier without a potential language barrier.

[38]Craccum, no. 22 (2003), 36.

[39]One News at 6. Aired 14 January 2021, on TVNZ 1; University of Auckland TV and Radio Service, accessed 25 January 2021, https://www.library.auckland.ac.nz/tv-radio/title/VA_28120_02.

[40]Jared Savage, “Foreign Student Service Bridges the Gap”, Auckland City Harbour News, 16 June 2004.