Part Four

ESCAPING PARADISE: Prison Labour and Rangitoto Island

by Blair McIntosh*

For a place without a permanent resident population, it is striking how many amenities Rangitoto Island has to offer. Within only a few hundred meters of the Island’s simple yet stately main wharf, a smooth boardwalk leads visitors past a sizeable concrete swimming pool, modest changing shed and neat DOC information hut. Walk just beyond this, and day-trippers have the choice of either following a clear walking path along the coast or heading inland on a generous gravel road which snakes its way up to the summit.

What you are probably not aware of, however, is exactly how these facilities were built. Far from the romanticised image we might have of ‘pioneering folk’ breaking in this unruly outpost of Auckland’s frontier, the development of Rangitoto has also been intimately bound up with an altogether different history: a history of prison labour.

Between 1925-1935, some 340 prisoners were housed in work camps located on the Island in order to perform enforced manual labour. These prisoners, originally from Auckland (now Mt Eden) Prison were regularly cycled on and off the Island as part of an agreement reached between the Department of Justice and the Rangitoto Island Domain Board in 1925. Attempts to utilise prisoners to ‘improve’ the Island can be traced as far back as 1872, when Auckland-based newspapers implored the Government to “pay a reasonable expenditure to employ the convicts and other criminal prisoners” in the newly-created Islington Bay Quarry. Although this proposal was ultimately unsuccessful, only half a century later the first cohort of twelve inmates and two prison wardens were approved by the Department of Justice to relocate to Rangitoto Island in order to establish a new scoria quarry for public works. Quarrying would remain the primary form of labour performed by inmates for the next ten years, who were quickly set to work improving the Island’s rudimentary infrastructure. It is worth nothing that nearly all communal facilities the Island’s bach owners perceived themselves as having ‘contributed’ to Rangitoto—Islington Bay Jetty, numerous coastal pathways, dance hall, tennis courts, playground and swimming pool to name a few—had stonework laid or were located on parcels of land painstakingly levelled by prison work gangs. Indeed, Angela Woolnough estimates that the value of this unpaid work was equivalent to £25,000 — $2.8 million in today’s rates.

View of the concrete swimming pool and gravel road as seen by visitors today. All had stonework laid by prison labour. Photographs author’s own.

The juxtaposition of using prison labour to build infrastructure on the ‘holiday’ hotspot of Rangitoto Island is rendered even clearer by the body of discourse that surrounded prisons in the 1920s and 1930s. Quite unlike the law-abiding public, prisoners were deemed individuals who ought to be deprived of leisure and pleasure as punishment for their criminality. Indeed, many leading prison reformers at the time argued that there was a strong connection between too much leisure and deviant behaviour, as a lack of purpose bred ‘delinquency and avarice’ amongst social ‘misfits’. According to this prevailing discourse, criminals were not capable of cultivating ‘healthy’ pastimes because they had not yet learnt the physical, mental and moral value of hard work. Enforced labour was seen as imperative to correct this deficiency, helping reform prisoners into ‘healthy’ and productive members of society. Isolated from the vice and temptation of the industrial city, Rangitoto Island—initially classified by the Department of Justice as part of the ‘Dominion’s third-class and waste land’—made the ideal location. As this report written on the Island’s first ‘Handy Dozen’ prison work gang in November 1925 betrays, a sizeable portion of Aucklanders were convinced of Rangitoto’s reformative effects for those who had ‘previously strayed’:

“These men were a selected dozen of the good conduct prisoners at Mount Eden, who were going to Rangitoto to commence work on the ambitious project of constructing a motor road to the summit of the grand and rugged volcanic isle… Three gaol officials were in charge of the gang, but dressed in mufti for the occasion they looked as mild-mannered men as ever used shoe polish. Their directions to the men were more in the nature of requests than orders, and they were obeyed with a cheerfulness that spoke of good relationships between gaoler and prisoner—quite a “happy family” sort of trip it seemed. The men chatted and laughed as they brought the stores aboard, as if they were off to a picnic, instead of the hard labour that must necessarily be the lot of those who are to cut a road through the lava rocks of Rangitoto.

Among the articles taken aboard were a number of new bright pointed picks—shuddersomely sharp they seemed. Instinctively there came to the mind a picture of the long ago, in the bad old convict days in Australia, when a chain-gang at Williamstown fell upon their tyrant taskmaster, Price, and hacked him to death, with just such picks as these, it may have been. However, prison methods and prison discipline are, fortunately, foreign to the terrible times described in the grim and tragic “For the Term of His Natural Life,” and these officials and prisoners looked just as foreign compared to those tyrants and brutes of days now fortunately distant. Looking at these men one wondered what rearing, what environment and what circumstances had brought them to this, and thanked the powers that be and great publicists such as Marcus Clarke and Charles Reade, who let people outside know of the awful barbarities of prison life in the past, that the punishment of the law is now more reformative than punitive”.

Yet there is a certain irony that only five months after this article was published, the first attempted prison escape from the Island took place. It suggests that far from the ‘happy family” prison reformers suggested manual convict labour on Rangitoto was capable of achieving, there were more than a few dissenting opinions.

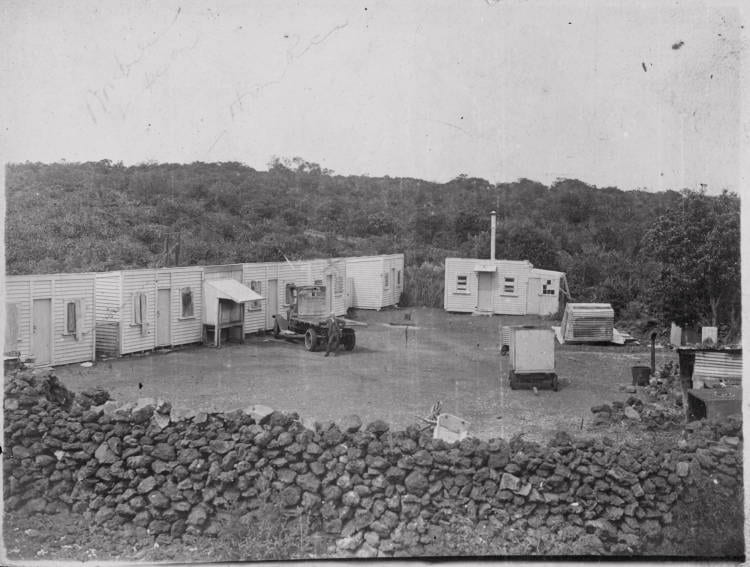

Photograph taken of the huts prisoners were to be housed in during their manual labour, staged for a visit by the Devonport Borough Council to inspect Rangitoto Island. Retrieved from Auckland Library Online archives: Record ID D-GR-0008.

I WANT TO BREAK FREE: PRISON ESCAPES ON RANGITOTO ISLAND

The first recorded attempt by prisoners to ‘escape’ Rangitoto Island took place in the early hours of February 17th, 1926 after the camp’s two wardens had done their late-night inspection of the huts. Unbeknownst to them, two of the camp’s prison labourers—William Wahle (23) and Samuel Rattray (33), both sentenced for forgery—had greased the hinges to their hut’s door so the security bolt could be quietly pushed open.

After successfully managing to do so around 12:30am, Wahle and Rattray made a dash for bach owner D.S Donaldson’s dingy, which included an outboard motor, grappling iron and iron winch. It was not until 5:30am the next morning were the wardens alerted to the two prisoners’ disappearance, prompting a frenzied attempt to notify authorities on the mainland (since the Island had no telephone connection) that was only picked up by a signalman stationed on Mt Victoria at 7:10am. Although a police search party reached the Island by 9am, a full day of searches produced no tangible leads, prompting the police to issue a warning to residents near St Helier’s Bay to be on the lookout for the two ‘fugitives’, and all boat owners to immobilise their vessels by removing the battery.

William Wahle and Samuel Rattray, on their way to court to be sentenced. Photograph from NZ Truth, Issue 1058, 4 March 1925.

Conditions for Wahle and Rattray, meanwhile, had slowly started to worsen. Although their first night hiding out on Motihue Island had been uneventful, their decision to try on the second day to reach the mainland in strong swells resulted in their dingy being wrecked on the rocks off Church Bay in Waiheke. Unable to salvage the dingy or find one that had not been immobilised, both men decided to set off across the Island, hiding by day and walking by night. Although another police search on the second day proved unsuccessful, a string of strange burglaries on the remote side of Waiheke Island soon raised suspicions. Two residents on Waiheke Island reported that their baches had been broken into, and a variety of items ranging from blankets, binoculars, fish hooks, playing cards, tinned peaches to an automatic shotgun had been stolen.

After Mr and Mrs Connell noticed that nearly two kgs of bacon, a tin of biscuits, a tent fly, one onion, some soft drinks and a box of shotgun cartridges were missing, several residents and the Island’s local constable banded together to chase down Wahle and Rattray who had disappeared into the bush. After a two-hour manhunt, Wahle and Rattray handed themselves over to be arrested. Incredibly, when asked why they had attempted to escape from Rangitoto Island, both said that were simply attempting to arrive back at Mt Eden Prison, as they had grown tired of the two wardens who were “always at loggerheads”. It is fair to say that the judge who heard their case was not impressed with this answer, sentencing them both to an additional two years’ imprisonment with hard labour for being “incorrigible rouges”; and an additional twelve month’s imprisonment for stealing nearly £64 ($6,871.58 in today’s rates) worth of property.

Remarkably, this daring bid for freedom was not the only prison escape that occurred on Rangitoto Island. Eight years later, on May 17th 1934 two more prisoners—this time Roy Taylor (23) and James Macandrew (25), completing hard labour sentences for vehicle conversion and theft respectively—managed to break out of their prison hut during the early hours of the morning. Taylor and Macandrew then trekked nearly 5 kilometres in their flimsy prison slippers across Rangitoto Island until they reached Islington Bay, breaking into an unoccupied bach in order to steal supplies and tools capable of prying open a boat shed that contained a dingy.

After a routine warden inspection at 5:30am revealed that the prisoners were missing, a visiting group of Boy Scouts were employed to try and signal for help from the mainland, as the Island still lacked any telephone line. Eventually, the camp wardens were forced to flag down the Island’s routine mail ship Olive Jean, and order the captain to alert the authorities once back in Auckland. This meant that waterfront Police were not able to reach Rangitoto Island until 3:30pm, by which time Taylor and Macandrew had already made it to Brown’s Island. Despite sending out search parties to Waiheke and Motihue Island—the two locations visited in the previous prison escape—both parties returned to Auckland at 8:30pm without any compelling leads.

By the next morning, Taylor and Macandrew had managed to navigate their dingy into the mouth of the Tamaki River and beached their craft near Otahuhu. From there, both men walked across country following the Great South Road, reaching Papatoetoe by evening. After hiding by a nearby cinema, Roy Taylor put his vehicle conversion skills to good use, stealing moviegoer Mr D Johnson’s car sometime between 9-11pm and driving it down the Great South Road until its petrol ran out. While the two escapees were able to steal fuel from a petrol station at Ramarama to prolong their journey, they were not so lucky when they became stranded at Taupiri. Unable to find any farmers willing to give them fuel, the men resolved themselves to continue on foot.

Unfortunately for Taylor and Macandrew, their string of thefts had helped Police pinpoint their likely location. By lunchtime, both men were arrested near Gordonton, clearly exhausted and having not eaten since the night of their escape. When questioned by police over the reason for their attempted escape, both men said they were “fed up with it all” and “hated” their working conditions on Rangitoto Island. Moreover, Taylor also claimed he wanted to go see his wife who lived in Hamilton, and escaping was the only way of doing so. For this “wild unreasonable desire to get out of gaol”, the Judge sentenced Taylor and Macandrew to an additional six months’ imprisonment to be served at the expiration of their present terms, alongside another three months’ imprisonment for converting Mr Johnson’s car.

Although it is hard to say whether the second attempted prison escape was the final straw for the Department of Justice, a decision was made in late 1934 to discontinue all prison labour on Rangitoto Island. On March 2nd 1935, the last work gang of 20 men quietly departed Rangitoto’s shores and returned to Mount Eden Prison: marking the end of the Island’s colourful yet ignored convict past.

PRISONERS AND PICKAXES: MAKING SENSE OF CONVICT LABOUR’S LEGACY

The legacy Rangitoto’s story of prison labour leaves behind in its wake is a contradictory one.

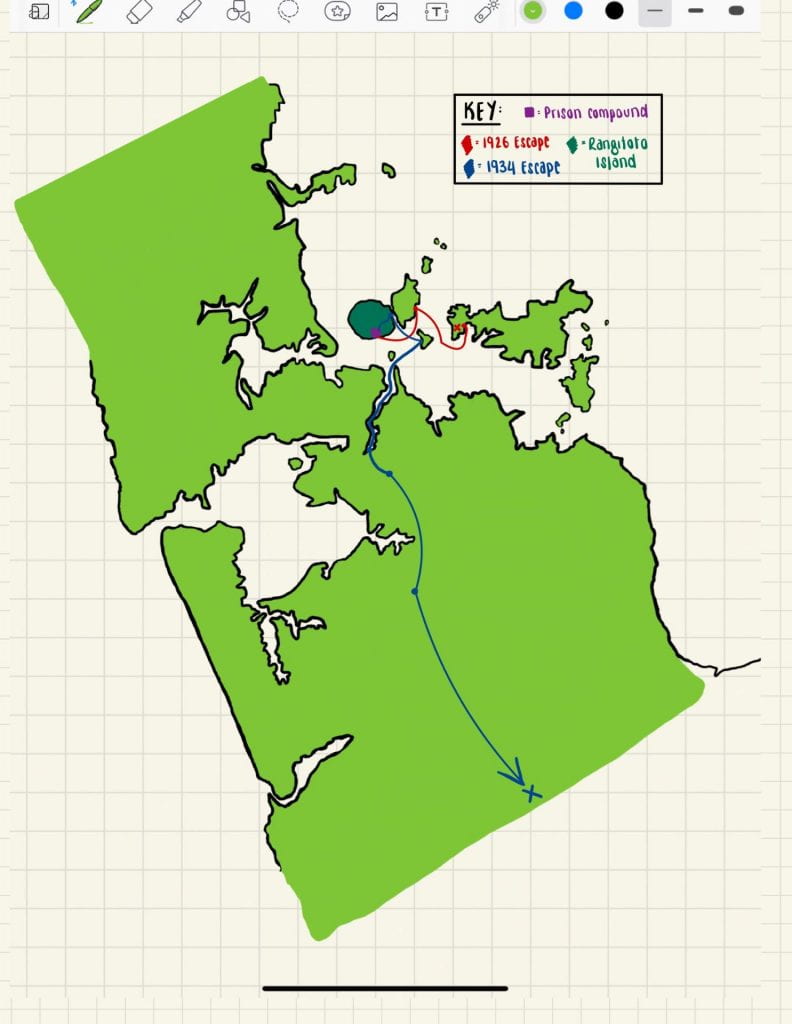

Illustration of routes taken during prison escapes in 1926 and 1934 respectively. Map courtesy of Reuben Bull (2022).

As this essay series has attempted to illustrate, for much of its history Rangitoto Island has been viewed as that place ‘out there’; a land of adventure, leisure, challenge and opportunity where you could momentarily shed your everyday identity from ‘over here’ and become someone new. But closer inspection of the Island’s history reveals that what made so much of this escapism possible was not in fact the product of self-stylised ‘pioneering folk’ but rather achieved through the uncompensated work of coerced prison labour. If the ‘Frontier’ is meant to embody a “new field of opportunity” and a place where “unrestraint is triumphant” as historian Frederick Jackson Turner opined, doesn’t the presence of prison labourers at Rangitoto Island undermine any claim to it being part of Auckland’s ‘restless frontier’?

Providing a definitive answer to this question is not easy.

On one hand, the extensive use of prison labour on Rangitoto Island goes against three core values we like to attribute to ‘the Frontier’ the most: hard work, self-reliance, and freedom. Legitimising these values matter to us, because they confirm our conviction in the Frontier as being some place unique, with its own distinct energy, vitality, vigour and purpose. However, throughout history, frontier spaces have always been built on coercion of marginalised ‘others’. Much of Britain’s gilded ‘Age of Scientific Exploration’, for example, was funded by the profits of slavery. Convict labour was used extensively in emerging nations like Argentina, Australia, Chile and New Zealand to break in new land and enable faster access to untapped resources. Indeed, while Frederick Jackson Turner might have been a principal inspirer of the cherished ‘American Frontier’, his actual thesis is riddled with racial overtones and consciously ignores the rights Native American communities had to the so-called ‘wilderness’ he encouraged white settlers to forcibly bring under the ‘yoke of civilisation’. It appears that far from undermining Rangitoto Island’s imagined status as a frontier space, the presence of prison labour might actually confirm its most uncomfortable truths.

REIMAGINING RANGITOTO REVISITED

I began this essay series with the intent of challenging Aucklanders to reconsider and reimagine Rangitoto Island’s place in our harbour. Crucially, Rangitoto has always occupied a liminal space between ‘over here’ and ‘out there’; between the urbanity or mundaneness of Auckland and a place capable of representing the imagined frontier of a wilder, even hallowed, place from earlier in time. As each successive wave of Aucklanders sought to make Rangitoto their own— be they self-professed ‘explorers’, daring ‘frontiersmen’ or finally the Island’s bach-based ‘settlers’—the struggle to tame the maunga allowed them to recast themselves as testing the limits of their character and project onto the island the hope and aspirations they for transformative change.

I have used the word ’imagined’ throughout my essay series because in many ways, that is what a frontier ultimately is: less a definitive thing that can be objectively mapped and assessed but rather a persuasive state of mind we have come to believe might be the antidote to the increasing dissatisfaction of our ever-urbanising times. As the history of prison labour wisely reminds us, such a sentiment more accurately reflects our own wistful nostalgia than it does any historical reality. Rangitoto Island is a place where challenge, opportunity and change coalesce but also contradictions, paradoxes and tensions too.

It is tempting for us to think that we already know everything there is to know about that Island which lies in the middle of our harbour. Its sight is so familiar.

Yet when we delve beneath the surface, we begin to see another side of this iconic landmark emerge. Rangitoto is more than an inconsequential part of our waterfront scenery. Its history should challenge us to revise the ways we think about our city’s places, and more importantly, what it means to be an ’Aucklander’ today.

Hopefully, this essay series is one step towards achieving that.