Part Three

Experiencing Yugoslavia

by Slavenka Misa (nee Sumich)

The returnees understood that they were going to a war damaged land but articles in the Napredak newspaper had filled them with optimism that reconstruction and social and economic progress was forging ahead. They expected to tighten their belts for a while then afterwards to thrive in the promised utopia. The New Zealand returnees would have been like the Australians in that,

…although they truly believed intellectually that they understood the conditions in Yugoslavia, few of the Australian (returnees) had any real appreciation of the horror and deprivation experienced by Slavs during the war… 3,500,000 were rendered homeless. Livestock and poultry stocks were decimated, as were industries, hospitals, and schools. By 1948, while the situation had improved, there were still severe food and housing shortages.

All the returnees who traveled on the Radnik and the Partizanka had six weeks of leave to visit relatives when they first arrived in Yugoslavia. Then they were allocated accommodation and directed to jobs or to the youth brigade work camps. Seven weeks after reaching Yugoslavia Steve Mrkusic, Gordon Sunde, Victor Sunde and Ivan Sumich joined the volunteer work brigades for 60 days of manual labour building roads and railways throughout Yugoslavia. They and five others from the Radnik voyage were in the same brigade of local Dalmatian youth volunteers.

Their Youth Brigade was separate from the International Youth Brigade. The International Youth Brigades were made up of student volunteers from many European nations. They had idealistic notions about assisting the development of a truly socialist state. They admired Marshall Tito and the Partizans and saw that they could help rebuild the roads and rail lines of Yugoslavia which had been damaged or destroyed by four years of war. Tito could see that these young people would be good messengers for his propaganda, so they were treated as guests. The International Youth Brigade was ‘… a privileged group…their accommodation and food at the construction sites greatly exceeded that which was provided for the local youth brigades.”

The New Zealanders were sent to a local Youth Brigade where the conditions were more spartan. The young New Zealanders felt that they should not be given special treatment and staunchly endured the circumstances. Steve Mrkusic described his experience in his memoir:

Upon arrival (in camp) all our heads were shorn for hygiene reasons. We were provided with work boots and a uniform that survived eight weeks.

Work was manual with pick and shovel, digging suitable material to form a compatible base for the new highway, barrowing to light rail wagons which were manpowered to the roadworks. There was only one bulldozer which worked day and night.

We worked for 8 weeks building the new ‘Auto-put Bratstvo Jedinstvo’ (Motorway of Brotherly Unity) Our base camp consisted of two buildings that were sleeping quarters. No individual bunks; just two raised platforms, no mattresses. The toilet consisted of an open trench in the ground with a single rail for support. For four weeks we had no ablutions except four taps providing cold water …after which… showers were provided but they only worked for two weeks before the hot water boilers broke down.

The food was basic and lacked variety. Imitation coffee, corn bread, corn porridge, beans and cabbage. No meat or fish of any kind. At times we were hungry, Ivan Sumich (my cousin) did get a food parcel from Podgora which he shared with me. It was cheese and honey from Podgora.

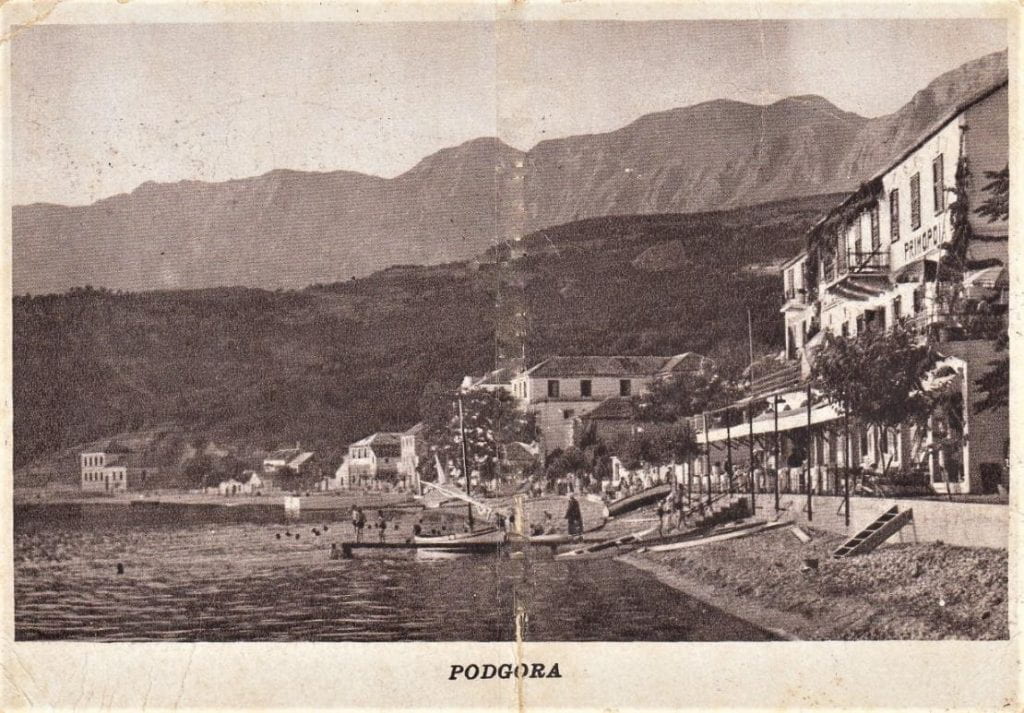

Postcard sent to Ivan Sumich when he was in the volunteer work brigade by his sister-in-law Olga Sumić referring to the food parcel the family sent to him and congratulating him on being given the ‘Shock-worker’ award. Ivan spent most of his stay in Yugoslavia in his home village of Podgora where he worked on family small holdings and helped his neighbours. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA

On one occasion when the potato crops in nearby fields tempted their hunger unbearably Steve recalls he and two friends

‘… tickled out a few potatoes from the edge of a field (without disturbing the plants too much) and cooked them in the embers of a fire as we had done sometimes as boys in New Zealand’.

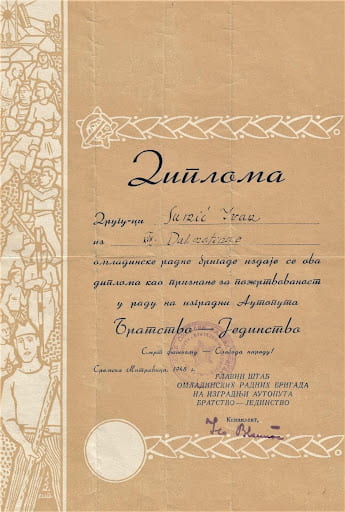

Despite the harrowing conditions, the young men from New Zealand completed their 60 days, and each volunteer worker received a certificate in honour of the season of labour they had served.

Certificate awarded to Ivan Sumich who was a member of the 18th Dalmatian youth brigade constructing the state Highway of Brotherly Unity in the summer of 1948. ORIGINAL COURTESY OF SLAVENKA MISA.

Living conditions in the villages were a shock to wives like Violet Skokandich who was born in New Zealand. There was no indoor plumbing or electricity. Violet was isolated from her own relations on the mainland and thousands of miles from her parents and sister in New Zealand. She lived in a tiny village in the middle of the island of Korčula off the Dalmatian coast. Food was in short supply. ‘Anything would be ground to make flour’ remembered Barbara, Violet’s daughter. The family occasionally received parcels from Barbara’s grandmother in Dargaville which contained

…white flour, white sugar, Bell tea and Highlander condensed milk. When the parcels came, we (Barbara and her brother Nick) waited with bated breath to see if there was any sweetened condensed milk. It was the favourite.

There was no milk or butter in the village. There were no cows only sheep and goats whose milk was used to make cheese. Nick Skokandich was a young boy during his stay in the village of Žrnovo on the island of Korčula but vividly remembers how scarce meat was. ‘When an animal was killed each family would be given a bit. Even the ears were shared out’.

The Skokandich family in Žrnovo, Korčula. L to R, Ljubica (Violet), Baba (Grandmother) Mare, Dida (Grandfather) Jerko, Nikola, in front L to R, Nick and sister Barbara c. 1949. PHOTO COURTESY OF NICK SKOKANDICH.

The Skokandich family were lucky that their father could hunt with his gun and dog that had travelled with him from New Zealand. The family’s diet was supplemented with snipe, hare, and wood pigeon. The children would also help by trapping small birds. This was Nick’s job. These would be skewered and roasted over a fire. They had the delicious aroma of the grapes and figs that they had eaten. Many years after returning to New Zealand this memory was awakened when Barbara Skokandich was being wined and dined at a fashionable restaurant. The dish was ‘Chicken Noreen’. It was brought flaming with brandy to the table. The aromatic fumes wafted her back in time to a far more rustic meal.

Food shortages were universal. In Zagreb, where Steve Mrkusic was a student of Civil Engineering, the student canteen where he ate all his meals provided

…a basic and unvaried menu of corn bread, corn porridge, beans, and cabbage with meat once a year on Tito’s birthday. There was food rationing and students were at the bottom rung of that ladder.

The ‘New Zealanders’ supported each other when they met. Steve was lucky in having as a friend, Dick Hrstich, who had also come from New Zealand and was a talented wrestler. Dick had been co-opted onto the Yugoslav national team and given an honorary commission with the police while he trained fulltime. When there were international competitions, and he was out of town the wrestler would give Steve his meal tickets for the police canteen so Steve could have his meals there. The food was much better and Steve’s presence was never questioned.

Accommodation was also scarce, but Steve was fortunate to be able to stay with his friend Gordon Sunde at his uncle’s apartment. Steve also received the occasional food parcel (from New Zealand) but more often parcels of saleable items like nylon combs. He also sold his bicycle, gun and ammunition to cover his expenses and gave English conversation lessons to a senior official who wanted to improve his pronunciation.

While Steve and the Sunde cousins, Gordon, and Victor, lived in Zagreb they became friends with the British consul and used to play tennis on his tennis court. During their second summer in Yugoslavia they visited relatives in the village of Podgora on the Dalmatian coast. Steve helped with the preparations for the reticulation of electricity to the village, unloading poles from a truck and laying them out along the designated line.

For children of school age and for tertiary students it was a challenge to communicate completely in Croatian. At home in New Zealand they would have become familiar with a basic vocabulary, often in a village dialect which was inadequate to manage their academic work. Steve was fortunate that the university library held many textbooks in English. Yet, despite the shortages, education and medical treatment were free for everyone. As Steve Mrkusic wrote: “… even though I was a foreigner I was not charged any fees… we had a 25% concession for train fares and free dental and medical care.

Politics and Disillusionment

There were developing tensions over the failure of joint economic deals between the USSR and Yugoslavia from 1946. Payments for food and other materials were delayed and partial. Tito’s insistence on independent control of Yugoslav foreign policy was the last straw for Stalin. Yugoslavia was expelled from the Cominform and Tito steered a dangerous, separate course.

Tito’s regime controlled the populace by punishing any discussion or expression of grievances. The situation was particularly tense once Yugoslavia was excluded from the Cominform on the 28 June 1948 and Tito and Stalin were at loggerheads. This led to the persecution of diehard communists who believed that Tito should cooperate with Stalin to maintain the unity of communist bloc countries. Some of these people were Partizan heroes yet they were incarcerated and even executed and New Zealand and Australian returnees did not escape persecution. Steve Mrkusic commented that

During my first semester Yugoslavia was expelled from the Russian Eastern Communist Bloc (Cominform)… When I enrolled the following year for my second semester Russian was no longer a requirement….I do not remember anyone I knew being imprisoned or shot, but a student colleague did not return after completing the first semester. I was cautioned by other students not to enquire why.

There was an increasing sense of disquiet and disillusionment amongst returnees from the Antipodes and most began to prepare to return ‘home’. Indeed, by the end of 1948, the passengers were regretting leaving New Zealand. Steve Mrkusic said that

Ivan Sumich… was the first to say (to him) that this is not a suitable place to live the remainder of our lives.

Gordon Sunde, a member of the Yugoslav Association and who had been an enthusiastic admirer of Yugoslavia when he set sail, was mightily disillusioned. He soon saw the ethnic divisions, the wartime devastation and learned that the locals had killed more of their own than the Germans. Without passports, money or necessary visas many returnees secretly planned their exit from Yugoslavia.

Any readers interested in discovering more about their Dalmatian roots or generally interested in the history of Dalmatians in Aotearoa New Zealand please contact the Dalmatian Archive and Museum

P.O.Box 8479

Symonds Street

Auckland 1010

Phone (09)303 0366

The DA&M is part of the Dalmatian Cultural Society and is housed on the ground floor of their building at

10 New North Road

Eden Terrace

Auckland